Felix Yusupov

Prince Felix Felixovich Yusupov, Count Sumarokov-Elston (Russian: Князь Фе́ликс Фе́ликсович Юсу́пов, Граф Сумаро́ков-Эльстон;[1] 23 March [O.S. 11 March] 1887 – 27 September 1967) was a Russian aristocrat, prince and count from the Yusupov family. He is best known for participating in the assassination of Grigori Rasputin and marrying the niece of Tsar Nicholas II.

| Prince Felix Yusupov | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Born | 23 March [O.S. 11 March] 1887 Moika Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire | ||||

| Died | 27 September 1967 (aged 80) Paris, France | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Princess Irina Alexandrovna of Russia | ||||

| Issue | Princess Irina Felixovna Yusupova | ||||

| |||||

| House | Yusupov | ||||

| Father | Count Felix Felixovich Sumarokov-Elston | ||||

| Mother | Princess Zinaida Nikolayevna Yusupova | ||||

Early life

He was born in the Moika Palace in Saint Petersburg, the capital of the Russian Empire. His father was Count Felix Felixovich Sumarokov-Elston, the son of Count Felix Nikolaievich Sumarokov-Elston. Zinaida Yusupova, his mother, was the last of the Yusupov line, of Tatar origin, and very wealthy. For the Yusupov name not to die out, his father (5 October 1856, Saint Petersburg – 10 June 1928, Rome, Italy) was granted the title and the surname of his wife, Princess Zinaida Yusupova upon their marriage, on 4 April 1882 in Saint Petersburg.

The Yusupov family, richer than any of the Romanovs, had acquired their wealth generations earlier. It included four palaces in Saint Petersburg, three palaces in Moscow, 37 estates in different parts of Russia (Kursk, Voronezh and Poltava), coal and iron-ore mines, plants and factories, flour mills and oil fields on the Caspian Sea.[2]

Felix led a flamboyant life and is thought to have been bisexual. When he addresses this claim in his book Lost Splendor, however, he flat out denied it.[3] From 1909 to 1913, he studied Forestry and later English at University College, Oxford,[4] where he was a member of the Bullingdon Club,[5] and established the Oxford Russian Club.[6] Yusupov was living on 14 King Edward Street, had a Russian cook, a French driver, an English valet, a housekeeper, and he spent much of his time partying. He owned three horses, a macaw and a bulldog called Punch. He smoked hashish,[5] played polo and became friendly with Luigi Franchetti, a piano player, and Jacques de Beistegui, who both moved in.[7] At some time, Yusupov got acquainted with Albert Stopford and Oswald Rayner. He rented an apartment in Curzon Street, Mayfair, and met several times with the ballerina Anna Pavlova, who lived in Hampstead.

.jpg)

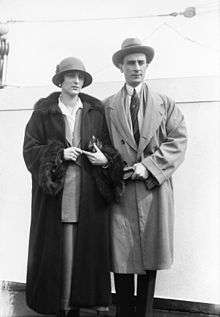

Marriage

Back in Saint Petersburg, he married Princess Irina of Russia, the Tsar's only niece, in the Anichkov Palace on 22 February 1914. The bride was wearing a veil that had belonged to Marie Antoinette.[8] The Yusupovs went on their honeymoon to Cairo, Jerusalem, London and Bad Kissingen, where his parents were staying.

World War I

When World War I broke out in August 1914, both were briefly detained in Berlin. Irina asked her relative, Crown Princess Cecilie of Prussia, to intervene with her father-in-law, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The Kaiser refused to permit the Yusupov family to leave but offered them a choice of three country estates to live in for the duration of the war. Felix's father appealed to the Spanish ambassador in Germany and won permission for them to return to Russia via neutral Denmark to the Grand Duchy of Finland and from there to Saint Petersburg[9] The Yusupovs' only daughter, Princess Irina Felixovna Yusupova, nicknamed Bébé, was born on 21 March 1915.[10] Bébé was largely raised by her paternal grandparents until she was nine. She was very spoiled by them. Her unstable upbringing caused her to become "capricious," according to Felix. Felix and Irina, raised mainly by nannies themselves, were ill-suited to take on the day-to-day burdens of child-rearing. Bebe adored her father but had a more distant relationship with her mother.[11]

After the death of his brother, Felix was the heir to an immense fortune. Consulting with family members about how best to administer the money and property, he decided to devote time and money to charitable works to help the poor. The losses at the Eastern Front were enormous, and so Felix converted a wing of the Liteyny Palace into a hospital for wounded soldiers.

Felix was able to avoid entering military service himself by taking advantage of a law exempting only-sons from serving. Irina's first cousin, Grand Duchess Olga, to whom she had been close when they were girls, was disdainful of Felix: "Felix is a 'downright civilian,' dressed all in brown, walked to and fro about the room, searching in some bookcases with magazines and virtually doing nothing; an utterly unpleasant impression he makes – a man idling in such times," Olga wrote to Nicholas on 5 March 1915 after paying a visit to the Yusupovs.[12] In February 1916 Felix began studies at the elite Page Corps military academy and tried joining a regiment in August.[13]

Killing of Rasputin

"Yusupov's plan, as he described it in his book, was to seek closer acquaintance with the healer Grigori Rasputin, and win his confidence. He asked Rasputin to cure a slight malady from which he suffered."[14] Yusupov first approached the lawyer Vasily Maklakov, who agreed to advise Felix.[15] Yusopov then approached Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an army officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment who was recovering from injuries who was a friend of his mother.[16] Grand Duke Dmitri received Yusupov's suggestion with alacrity, and his alliance was welcomed as indicating that the murder would not be a demonstration against the [Romanov] dynasty.[17]

On the night of 29/30 December (NS) 1916, Felix, Dmitri, Vladimir Purishkevich, assistant Stanilaus de Lazovert and Sukhotin killed Rasputin in the Moika Palace. A major reconstruction of the palace had almost been finished, with a small room in the basement carefully furnished. (For some time, Yusupov lived in a mansion owned by Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna of Russia, his mother-in-law.) Rasputin was hit by a bullet that entered his left chest and penetrated the stomach and the liver; a second entered the left back soon after the first and penetrated the kidneys. The wounds were serious, and Rasputin would have died in 10–20 min, but he succeeded in escaping, only to fall in the snow-clad courtyard. It is not clear whether or not Yusupov beat Rasputin with a sort of dumb bell. It is also not clear if it was Purishkevich who shot him in the forehead. The conspirators finally threw the corpse from Bolshoy Petrovsky Bridge into an ice hole in the Malaya Neva.

On the Empress's orders, a police investigation commenced and traces of blood were discovered on the steps to the back door of the Yusupov Palace. Prince Felix attempted to explain the blood with a story that one of his favourite dogs was shot accidentally by Grand Duke Dmitri. Yusupov and Dmitri were placed under house arrest in the Sergei Palace. (The upper levels of the palace were occupied by the British embassy and the Anglo-Russian Hospital.[18])

The Empress had refused to meet the two but said that they could explain what had happened in a letter to her. She wanted both shot immediately, but she was persuaded to back off from the idea.[18] Without a trial,[19] the Tsar sent Dmitri to the front in Persia; Purishkevich was already on his way to the front in Romania. The Tsar banished Yusupov to his estate[20] in Rakitnoye, Belgorod Oblast.

Yusupov published several accounts of the night and the events surrounding the murder. Recent authorities have cast doubt on Yusupov's account (see Grigori Rasputin).

Fuhrmann thinks that Yusupov was the man who hatched the plot and who carried it out. "The clumsy way the assassination was carried out shows it was the work of an amateur."[21] Fuhrmann also thinks Yusupov's "...candid Memoirs were corroborated by the other conspirators."[22]

Exile

One week after the February Revolution, Nicholas abdicated the throne on 2 March. Following the abdication, the Yusupovs returned to the Moika Palace before they went to Crimea. They later returned to the palace to retrieve jewels (including the blue Sultan of Morocco Diamond, the Polar Star Diamond, and a pair of diamond earrings that once belonged to Marie-Antoinette) and two paintings by Rembrandt, the sale proceeds of which helped sustain the family in exile. The paintings were bought by Joseph E. Widener in 1921 and are now in the National Gallery in Washington, DC.[23]

In Crimea, the family boarded a British warship, HMS Marlborough, which took them from Yalta to Malta. On the ship, Felix enjoyed boasting about the murder of Rasputin. One of the British officers noted that Irina "appeared shy and retiring at first, but it was only necessary to take a little notice of her pretty, small daughter to break through her reserve and discover that she was also very charming and spoke fluent English."[24]

From Malta, they travelled to Italy and then to Paris. In Italy, lacking a visa, he bribed the officials with diamonds. In Paris, they stayed a few days in Hôtel de Vendôme before they went on to London. In 1920, they returned to Paris.

Prince and Princess Yusupov lived between:

- 1920-1939 : 37, Rue Gutenberg then 19, Rue de La Tourelle in Boulogne-sur-Seine.[25]

- 1939-1940 : they rented a mansion in Sarcelles, Rue Victor-Hugo.[26]

- 1940-1943 : they moved to Rue Agar and 65, Rue La Fontaine (16th arrondissement of Paris).

- from 1943 until their death : 38, Rue Pierre-Guérin (Neuilly-Auteuil-Passy).

The Yusupovs founded a short-lived couture house Irfé, named after the first two letters of their first names.[27] Irina modeled some of the dresses the pair and other designers at the firm created. Yusupov became renowned in the Russian émigré community for his financial generosity. Their philanthropy and their continued high living and poor financial management extinguished what remained of the family fortune. Felix's bad business sense and the Wall Street Crash of 1929 eventually forced the company to shut down.[28]

Lawsuits

In 1932, he and his wife successfully sued MGM in the English courts for invasion of privacy and libel in connection with the film Rasputin and the Empress. The alleged libel was not that the character based on Felix had committed murder but that the character based on Irina, called "Princess Natasha" in the film, was portrayed as having been seduced by the lecherous Rasputin.[29] In 1934, the Yusupovs were awarded £25,000 damages, an enormous sum at the time, which was attributed to the successful arguments of their barrister, Sir Patrick Hastings. The disclaimer that now appears at the end of every American film, "The preceding was a work of fiction, any similarity to a living person etc.," first appeared as a result of the legal precedent set by the Yusupov case.[30]

In 1965, he also sued CBS in a New York court for televising a play based upon the Rasputin assassination. The claim was that some events were fictionalized, and under a New York State statute,[31] his commercial rights in his story had been misappropriated. The last reported judicial opinion in the case was a ruling by New York's second highest court that the case could not be resolved upon briefs and affidavits but must go to trial.[32] According to an obituary of CBS's lawyer, CBS eventually won the case.[33]

In 1928, after Yusupov published his memoir detailing the killing of Rasputin, Rasputin's daughter, Maria, sued Yusupov and Dmitri in a Paris court for damages of $800,000. She condemned both men as murderers and said any decent person would be disgusted by the ferocity of Rasputin's killing.[34] Maria's claim was dismissed. The French court ruled that it had no jurisdiction over a political killing that had occurred in Russia.[35]

Death

Irina and Felix enjoyed a happy and successful marriage for more than 50 years. When Felix died in 1967, Irina was stricken by grief and died three years later.[36] He was buried in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery, in the southern suburbs of Paris. Yusupov's private papers and a number of family artifacts and paintings are now owned by Víctor Contreras, a Mexican sculptor who, as a young art student in the 1960s, met Yusupov and lived with the family for five years in Paris.[37]

Some of the Yusupov possessions owned by Contreras were auctioned in November 2016 by Coutau Bégarie. This included correspondence with the family of his father's mistress, Zénaïde Gregorieff-Svetiloff.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Felix Yusupov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants

Descendants of Felix and Irina are:

- Princess Irina Felixovna Yusupova, (21 March 1915, Saint Petersburg, Russia – 30 August 1983, Cormeilles-en-Parisis, France), married Count Nikolai Dmitrievich Sheremetev (28 October 1904, Moscow, Russia – 5 February 1979, Paris, France), son of Count Dmitry Sergeevich Sheremetev and wife Countess Irina Ilarionovna Vorontzova-Dachkova and a descendant of Boris Petrovich Sheremetev; had issue:

- Countess Xenia Nikolaevna Sheremeteva (born 1 March 1942, Rome, Italy), married on 20 June 1965 in Athens, Greece, to Ilias Sfiris (born 20 August 1932, Athens, Greece); had issue:

- Tatiana Sfiris (born 28 August 1968, Athens, Greece), married on May 1996 in Athens to Alexis Giannakoupoulos (born 1963), divorced, no issue; married Anthony Vamvakidis and has issue:

- Marilia Vamvakidis (born 7 July 2004)

- Yasmine Xenia Vamvakidis (born 17 May 2006)

- Tatiana Sfiris (born 28 August 1968, Athens, Greece), married on May 1996 in Athens to Alexis Giannakoupoulos (born 1963), divorced, no issue; married Anthony Vamvakidis and has issue:

- Countess Xenia Nikolaevna Sheremeteva (born 1 March 1942, Rome, Italy), married on 20 June 1965 in Athens, Greece, to Ilias Sfiris (born 20 August 1932, Athens, Greece); had issue:

Bibliography

- Yusupov, Prince Felix: Rasputin, Dial Press, 1927

- Yusupov, Prince Felix: Rasputin: His Malignant Influence and His Assassination, 1934

- Yusupov, Prince Felix: Avant L'Exil, Plon, Paris 1952

- Yusupov, Prince Felix: Lost Splendour, Jonathan Cape, London 1953

- Ferrand, Jacques (Ed.): Les princes Youssoupoff & les comtes Soumarokoff-Elston, Ferrand, Paris 1991

References

- Variously transliterated from Cyrillic as Yussupov, Yusupov, Yossopov, Iusupov, Youssoupov, Youssoupoff, or as Feliks, Graf Sumarrokow-Elston.

- "Yusupov Palace". guide-guru.com. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Gretchen Haskin (2000) His Brother's Keeper. Atlantic Magazine; Lost Splendour, p. 111. Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Danzinger, Christopher (12 December 2016). "The Oxford alumnus who helped to assassinate Rasputin". www.oxfordtoday.ox.ac.uk. University of Oxford. Oxford Today. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Prince Yusupoff Defended in Rasputin Case - Fellow-Collegian at Oxford Tells of Nobleman's Career There, and Says It Is Impossible to Associate Him with a Murder 14 January 1917 The New York Times

- "About Us". OURS. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Lost Splendor, chapter XV

- J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 198.

- G. King, pp. 114–115.

- King, p. 116

- King, pp. 257–258

- Bokhanov, Alexander, Knodt, Dr. Manfred, Oustimenko, Vladimir, Peregudova, Zinaida, Tyutyunnik, Lyubov, editors, The Romanovs: Love, Power, and Tragedy, Leppi Publications, 1993, p. 240

- Ronald C. Moe (2011) Prelude to the Revolution: The Murder of Rasputin, p. 494-495.

- B. Pares (1939), p. 400.

- M. Nelipa, p. 112-115.

- M. Nelipa, p. 130, 134.

- B. Pares (1939), p. 402.

- M. Nelipa, p. 108.

- B. Almasov, p. 214; B. Pares, p. 146.

- "Род Князей Юсуповых, Дворцовый комплекс Юсуповых в Ракитном". yusupov.org. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 221.

- J.T. Fuhrmann, p. 201.

- "Art Object Page". nga.gov. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- King, p. 209

- Almanach de Gotha 1936, 3ème partie, page 698.

- "Maison de Félix Youssoupov". Topic-Topos. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Suzy Menkes (1 July 2008). "Russian revival at Irfe". The New York Times.

- "Russian label Irfe rises from its ashes in Paris". Otago Daily Times. 2 July 2008.

- King, p. 240-241

- NZ Davis "Any Resemblance to Persons Living or Dead": Film and the Challenge of Authenticity, The Yale Review, 86 (1986–87): 457–82.

- NY Civil Rights Act, art.50-51

- Youssoupoff v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., 19 A.D.2d 865 (1963)

- Thomas W. Ennis (6 September 1983). "CARLETON ELDRIDGE JR., LAWYER". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2017 – via www.nytimes.com. (obituary of Carleton G. Eldridge Jr.)

- King, Greg, The Man Who Killed Rasputin, Carol Publishing Group, 1995, ISBN 0-8065-1971-1, p. 232

- King, p. 233

- King, p. 275.

- Secrets of an Exiled Prince, Moscow Times, 11–17 April 2008.

Sources

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin, the untold story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 314. ISBN 978-1-118-17276-6.

- Greg King (1994) The Last Empress. The Life & Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, tsarina of Russia. A Birch Lane Press Book.

- Margarita Nelipa (2010) The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin. A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire, Gilbert's Books. ISBN 978-0-9865310-1-9.

- Bernard Pares (1939) The Fall of the Russian Monarchy. A Study of the Evidence. Jonathan Cape. London.

- Vladimir Pourichkevitch (1924) Comment j'ai tué Raspoutine. Pages de Journal. J. Povolozky & Cie. Paris

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Felix Yusupov. |

- The Yusupovs' Palace on Moika, Saint Petersburg – Family nest until 1919

- Lost Splendour – Yusupov's self-biography until 1919 (online). Printed in 1952, ISBN 1-885586-58-2.

- Felix Yusupov at Find a Grave

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140201200700/http://www.rulit.net/books/the-last-tsar-emperor-michael-ii-read-311858-26.html