Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna of Russia

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna of Russia (Olga Nikolaevna Romanova) (Russian: Великая Княжна Ольга Николаевна, IPA: [vʲɪˈlʲikəjə knʲɪˈʐna ˈolʲɡə nʲɪkɐˈlaɪvnə] (![]()

| Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna, c. 1914 | |||||

| Born | 15 November 1895[1] Alexander Palace, Tsarskoye Selo, Saint Petersburg Governorate, Russian Empire | ||||

| Died | 17 July 1918 (aged 22) Ipatiev House, Yekaterinburg, Russian Soviet Republic | ||||

| Burial | 17 July 1998 Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation | ||||

| |||||

| House | Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov | ||||

| Father | Nicholas II of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Alix of Hesse | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | ||||

During her lifetime, Olga's future marriage was the subject of great speculation within Russia. Matches were rumored with Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia, Crown Prince Carol of Romania, Edward, Prince of Wales, eldest son of Britain's George V, and with Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia. Olga herself wanted to marry a Russian and remain in her home country. During World War I, she nursed wounded soldiers in a military hospital until her own nerves gave out and, thereafter, oversaw administrative duties at the hospital.

Olga's murder following the Russian Revolution of 1917 resulted in her canonization as a passion bearer by the Russian Orthodox Church. In the 1990s, her remains were identified through DNA testing and were buried in a funeral ceremony at Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg along with those of her parents and two of her sisters.

Early life and childhood

Olga's siblings were Grand Duchesses Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Tsarevich Alexei of Russia. Her Russian title (Velikaya Knyazhna Великая Княжна) is most precisely translated as "Grand Princess", meaning that Olga, as an "imperial highness", was higher in rank than other princesses in Europe who were "royal highnesses". However, "Grand Duchess" is the usual English translation.[2] Olga's friends and family generally called her simply Olga Nikolaevna or nicknamed her "Olishka", "Olenka" or "Olya". Among her godparents was her great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. Olga was most often paired with her sister Tatiana. The two girls shared a room, dressed alike, and were known as "The Big Pair".[3]

From her earliest years she was known for her compassionate heart and desire to help others, but also for her temper, blunt honesty and moodiness. As a small child, she once lost patience while posing for a portrait painter and told the man, "You are a very ugly man and I don't like you one bit!"[4] The Tsar's children were raised as simply as possible, sleeping on hard camp cots unless they were ill, taking cold baths every morning.[5] Servants called Olga and her siblings by their first names and patronyms rather than by their imperial titles.[3] However, Olga's governess and tutors also noted some of the autocratic impulses of the daughter of the Tsar of All the Russias, one of the wealthiest men in the world. On a visit to a museum where state carriages were on display, Olga once ordered one of the servants to prepare the largest and most beautiful carriage for her daily drive. Her wishes were not honored, much to the relief of her governess, Margaretta Eagar. She also felt the rights of eldest children should be protected. When she was told the Biblical story of Joseph and his coat of many colors, she sympathized with the eldest brothers rather than Joseph. She also sympathized with Goliath rather than David in the Biblical story of David and Goliath.[4] When her French tutor, Pierre Gilliard, was teaching her the formation of French verbs and the use of auxiliaries, ten-year-old Olga responded, "I see, monsieur. The auxiliaries are the servants of the verbs. It's only poor 'avoir' which has to shift for itself."[6] Olga loved to read and, unlike her four siblings, enjoyed school work. "The eldest, Olga Nicolaevna, possessed a remarkably quick brain", recalled her Swiss tutor, Pierre Gilliard. "She had good reasoning powers as well as initiative, a very independent manner, and a gift for swift and entertaining repartee."[6] She enjoyed reading about politics and read newspapers. Olga also reportedly enjoyed choosing from her mother's book selection. When she was caught taking a book before her mother read it, Olga would jokingly tell her mother that Alexandra must wait to read the novel until Olga had determined whether it was an appropriate book for her to read.[7]

Margaret Eagar also noted that Olga was bright but said she had little experience with the world because of her sheltered life. She and her sisters had little understanding of money because they had not had an opportunity to shop in stores or to see money exchange hands. Young Olga once thought that a hat maker who came to the palace had given her a new hat as a present. Olga was once frightened when she witnessed a policeman arresting someone on the street. She thought the policeman would come to arrest her because she had behaved badly for Miss Eagar. When reading a history lesson, she remarked that she was glad she lived in current times, when people were good and not as evil as they had been in the past. When she was eight, in November 1903, Olga learned about death first hand when her first cousin, Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine, died of typhoid fever while on a visit to the Romanovs at their Polish estate. "My children talked much of cousin Ella and how God had taken her spirit, and they understood that later God would take her body also to heaven", wrote Eagar. "On Christmas morning when Olga awoke, she exclaimed at once, 'Did God send for cousin Ella's body in the night?' I felt startled at such a question on Christmas morning, but answered, 'Oh, no, dear, not yet.' She was greatly disappointed, and said, 'I thought He would have sent for her to keep Christmas with Him.'"[4]

Adolescence and relationships with parents

"Her chief characteristics … were a strong will and a singularly straightforward habit of thought and action", wrote her mother's friend Anna Vyrubova, who recalled Olga's hot temper and her struggles to keep it under control. "Admirable qualities in a woman, these same characteristics are often trying in childhood, and Olga as a little girl sometimes showed herself willful and even disobedient."[8] Olga idolized her father and wore a necklace with an icon of St. Nicholas on her chest.[9] She, like her siblings, enjoyed games of tennis and swimming with her father during their summer holidays and often confided in him when she went with him on long walks.[7] Though she also loved Alexandra, her relationship with her mother was somewhat strained during her adolescence and early adulthood. "Olga is always most unamiable about every proposition, though may end by doing what I wish", wrote Alexandra to Nicholas on 13 March 1916. "And when I am severe – sulks me."[10] In another letter to Nicholas during World War I, Alexandra complained that Olga's grumpiness, bad humor and general reluctance to make an official visit to the hospital where she usually worked as a Red Cross nurse made things difficult.[11] Olga also occasionally found her mother's attitude trying. Parlormaid Elizaveta Nikolaevna Ersberg told her niece that the Tsar paid closer attention to the children than Alexandra did and Alexandra often was ill with a migraine or quarreled with the servants.[12] In 1913, Olga complained in a letter to her grandmother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna about her mother's invalidism. "As usual her heart isn't well", Olga wrote. "It's all so unpleasant."[13] Queen Marie of Romania, who met Olga and her sisters when they visited Romania on a state trip in 1914, commented in her memoirs that the girls were natural and confided in her when Alexandra wasn't present, but when she appeared "they always seemed to be watching her every expression so as to be sure to act according to her desires."[14]

As an adolescent, Olga received frequent reminders from her mother to be an example for the other children and to be patient with her younger sisters and with her nurses. On 11 January 1909, Alexandra admonished thirteen-year-old Olga for rudeness and bad behavior. She told the teenager that she must be polite to the servants, who looked after her well and did their best for her, and she should not make her nurse "nervous" when she was tired and not feeling well.[15] Olga responded on 12 January 1909 that she would try to do better but it wasn't easy because her nurse became angry and cross with her for no good reason.[16] However, Ersberg, one of the maids, told her niece that the servants sometimes had good reason to be cross with Olga because the eldest grand duchess could be spoiled, capricious, and lazy.[17] On 24 January 1909, Alexandra scolded the active teenager, who once signed another of her letters with the nickname "Unmounted Cossack", again: "You are growing very big — don't be so wild and kick about and show your legs, it is not pretty. I never did so when your age or when I was smaller and younger even."[18]

Three years later, Alexandra blamed sixteen-year-old Olga, who was sitting beside her seven-year-old brother, for failing to control the misbehaving Tsarevich Alexei during a family dinner. The spoiled Alexei teased others at the table, refused to sit up in his chair, wouldn't eat his food and licked his plate. The Tsarina's expectation was unreasonable, said Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich of Russia, a distant cousin of the imperial family. "Olga cannot deal with him", he wrote in his diary on 18 March 1912.[19] Court official A. A. Mossolov wrote that Olga was already seventeen, but still "she had the ways of a flapper", referring to her rough manners and liking for exuberant play.[20]

Relationship with Grigori Rasputin

Despite this occasional misbehavior, Olga, like all her family, doted on the long-awaited heir Tsarevich Alexei, or "Baby". The little boy suffered frequent attacks of hemophilia and nearly died several times. Like their mother, Olga and her three sisters were also potentially carriers of the hemophilia gene. Olga's younger sister Maria reportedly hemorrhaged in December 1914 during an operation to remove her tonsils, according to her paternal aunt Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia, who was interviewed later in her life. The doctor performing the operation was so unnerved that he had to be ordered to continue by Tsarina Alexandra. Olga Alexandrovna said she believed all four of her nieces bled more than was normal and believed they were carriers of the hemophilia gene like their mother, who inherited the trait from her maternal grandmother Queen Victoria.[21] Symptomatic carriers of the gene, while not haemophiliacs themselves, can have symptoms of hemophilia including a lower than normal blood clotting factor that can lead to heavy bleeding.[22]

Olga's mother relied on the counsel of Grigori Rasputin, a Russian peasant and wandering starets or "holy man", and credited his prayers with saving the ailing Tsarevich on numerous occasions. Olga and her siblings were also taught to view Rasputin as "Our Friend" and to share confidences with him. In the autumn of 1907, Olga's aunt Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia was escorted to the nursery by the Tsar to meet Rasputin. Olga, her sisters and brother, were all wearing their long white nightgowns. "All the children seemed to like him", Olga Alexandrovna recalled. "They were completely at ease with him."[23]

However, one of the girls' governesses, Sofia Ivanovna Tyutcheva, was horrified in 1910 that Rasputin was permitted access to the nursery when the four girls were in their nightgowns and wanted him barred. Although Rasputin's contacts with the children were completely innocent, Nicholas asked Rasputin to avoid going to the nurseries in the future to avoid further scandal. Alexandra eventually had the governess fired. Tyutcheva took her story to other members of the family.[24] Nicholas's sister Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna of Russia was horrified by Tyutcheva's story. She wrote on 15 March 1910 that she couldn't understand:

- "…the attitude of Alix and the children to that sinister Grigory (whom they consider to be almost a saint, when in fact he's only a khlyst!) He's always there, goes into the nursery, visits Olga and Tatiana while they are getting ready for bed, sits there talking to them and caressing them. They are careful to hide him from Sofia Ivanovna, and the children don't dare talk to her about him. It's all quite unbelievable and beyond understanding."[25]

Maria Ivanovna Vishnyakova, another nurse for the royal children, was at first a devotee of Rasputin, but later was disillusioned by him. She claimed that she was raped by Rasputin in the spring of 1910.[26] The Empress refused to believe her and said that everything Rasputin did was holy. Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna was told that Vishnyakova's claim had been immediately investigated, but "they caught the young woman in bed with a Cossack of the Imperial Guard." Vishnyakova was dismissed from her post in 1913.[26]

It was whispered in society that Rasputin had seduced not only the Tsarina but also the four Grand Duchesses.[27] Rasputin had released ardent, though by all accounts completely innocent in nature, letters written by the Tsarina and the four grand duchesses to him. They circulated throughout society, fueling rumors. Pornographic cartoons circulated depicting Rasputin having relations with the empress, with her four daughters and Anna Vyrubova nude in the background.[28] Nicholas ordered Rasputin to leave St. Petersburg for a time, much to Alexandra's displeasure, and Rasputin went on a pilgrimage to Palestine.[29] Despite the rumors, the imperial family's association with Rasputin continued until Rasputin was murdered on 17 December 1916. "Our Friend is so contented with our girlies, says they have gone through heavy 'courses' for their age and their souls have much developed", Alexandra wrote to Nicholas on 6 December 1916, a few weeks before Rasputin was killed.[30] However, as she grew older, Olga was less inclined to see Rasputin as her friend and was more aware of how his friendship with her parents affected the stability of her country. Olga wrote in her diary the day after the murder that she suspected Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia, her first cousin once removed and the man she had at one time been expected to marry, was the murderer of "Father Grigory."[31] Dmitri and Felix Yussupov, the husband of her first cousin Princess Irina of Russia, were among the murderers. In his memoirs, A. A. Mordvinov reported that the four grand duchesses appeared "cold and visibly terribly upset" by Rasputin's death and sat "huddled up closely together" on a sofa in one of their bedrooms on the night they received the news. Mordvinov reported that the young women were in a gloomy mood and seemed to sense the political upheaval that was about to be unleashed.[32] Rasputin was buried with an icon signed on the reverse side by Olga, her sisters and mother. However, Olga was the only member of the family who did not attend Rasputin's funeral, according to the diary of her first cousin once removed Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich of Russia.[33] Olga's own diary however shows that she did attend his funeral. She wrote on 21 December (Old Style) 1916 "At 9 o' clock, we 4, Papa and Mama went to the place where Ania's construction is for the service of Litia and burial of Father Grigory."[34] According to the memoirs of Valentina Ivanovna Chebotareva, a woman who nursed with Olga during World War I, Olga said in February 1917, about a month after the murder, that while it might have been necessary for Rasputin to be killed, it should never have been done "so terribly." She was ashamed that the murderers were her relatives.[35] After Olga and her sisters had been killed, the Bolsheviks found that each was wearing an amulet bearing Rasputin's image and a prayer around their necks.[36]

Inspired by her religious upbringing, Olga took control of a portion of her sizable fortune when she was twenty and began to respond independently to requests for charity. One day when she was out for a drive she saw a young child using crutches. She asked about the child and learned that the youngster's parents were too poor to afford treatment. Olga set aside an allowance to cover the child's medical bills.[37] A court official, Alexander Mossolov, recalled that Olga's character was "even, good, with an almost angelic kindness" by the time she was a young woman.[38]

Romances and marital prospects

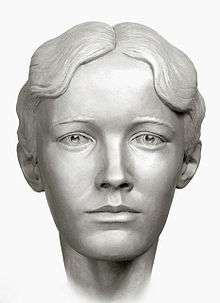

Olga was a chestnut-blonde with bright blue eyes, a broad face and a turned up nose. She was considered less pretty than her sisters Maria and Tatiana,[39] though her appearance improved as she grew older. "As a child she was plain, at fifteen she was beautiful", wrote her mother's friend Lili Dehn. "She was slightly above the medium height, with a fresh complexion, deep blue eyes, quantities of light chestnut hair, and pretty hands and feet."[40]

Olga and her younger sisters were surrounded by young men assigned to guard them at the palace and on the imperial yacht Standart and were used to mingling with them and sharing holiday fun during their annual summer cruises. When Olga was fifteen, a group of officers aboard the imperial yacht gave her a portrait of Michelangelo's nude David, cut out from a newspaper, as a present for her name day on 11 July 1911. "Olga laughed at it long and hard", her indignant fourteen-year-old sister Tatiana wrote to her aunt Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia. "And not one of the officers wishes to confess that he has done it. Such swine, aren't they?"[41]

At the same time the teenage Olga was enjoying her innocent flirtations, society was buzzing about her future marriage. In November 1911 a full dress ball was held at Livadia to celebrate her sixteenth birthday and her entry into society. Her hair was put up for the first time and her first ballgown was pink. Her parents gave her a diamond ring and a diamond and pearl necklace as a birthday present and symbol that she had become a young woman.[42] A. Bogdanova, the wife of a general and hostess of a monarchist salon, wrote in her diary the following summer, on 7 June 1912, that Olga had been betrothed the previous night to Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia, her first cousin once removed. In his book The Rasputin File, Edvard Radzinsky speculates that the betrothal was broken off due to Dmitri's dislike for Grigori Rasputin, his association with Felix Yussupov and rumors that Dmitri was bisexual.[43] However, no other sources mention an official betrothal to Dmitri Pavlovich. Before World War I, there was also some discussion of a marriage between Olga and Prince Carol of Romania, but Olga did not like Carol. During a visit to Romania in the spring of 1914, she struggled to make small talk with the Romanian crown prince.[44] Carol's mother, Queen Marie of Romania, was unimpressed with Olga as well, finding her manners too brusque and her broad, high cheek-boned face "not pretty."[45] The plans were, in any event, put on hold upon the outbreak of war in 1914. Edward, Prince of Wales, eldest son of England's George V, and Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia were also discussed as potential suitors, though none were considered seriously. Olga told Gilliard that she wanted to marry a Russian and remain in her own country. She said her parents would not force her to marry anyone she could not like.[46]

While society was discussing matches with princes, Olga fell in love with a succession of officers. In late 1913, Olga fell in love with Pavel Voronov, a junior officer on the imperial yacht Standart, but such a relationship would have been impossible due to their differing ranks. Voronov was engaged a few months later to one of the ladies in waiting. "God grant him good fortune, my beloved", a saddened Olga wrote on his wedding day, "It's sad, distressing."[47] Later, in her diaries of 1915 and 1916, Olga frequently mentioned a man named Mitya with great affection.[10]

According to the diary of Valentina Chebotareva, a woman who nursed with Olga during World War I, Olga's "golden Mitya" was Dmitri Chakh-Bagov, a wounded soldier she cared for when she was a Red Cross nurse. Chebotareva wrote that Olga's love for him was "pure, naive, without hope" and that she tried to avoid revealing her feelings to the other nurses. She talked to him regularly on the telephone, was depressed when he left the hospital, and jumped about exuberantly when she received a message from him. Dmitri Chakh-Bagov adored Olga and talked of killing Rasputin for her if she only gave the word, because it was the duty of an officer to protect the imperial family even against their will. However, he also reportedly showed other officers the letters Olga had written to him when he was drunk.[48] Another young man, Volodia Volkomski, appeared to have affection for her as well. "(He) always has a smile or two for her", wrote Alexandra to Nicholas on 16 December 1916.[49] Chebotareva also noted in her diary Olga's stated "dreams of happiness: "To get married, [to] always live in the countryside [in] winter and summer, [to] see only good people [and] no one official."[50] Other suitors within the family were suggested, among them Olga's first cousin once removed Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich of Russia. Alexandra refused to entertain the idea of her innocent daughter marrying the jaded, much older Boris Vladimirovich. "An inexperienced girl would suffer terribly, to have her husband 4, or 5th hand or more", Alexandra wrote.[51] She was also aware that Olga's heart lay elsewhere.[52]

Early adulthood and World War I

Olga experienced her first brush with violence at age fifteen, when she witnessed the assassination of the government minister Pyotr Stolypin during a performance at the Kiev Opera House. "Olga and Tatiana had followed me back to the box and saw everything that happened", Tsar Nicholas II wrote to his mother, Dowager Empress Maria, on 10 September 1911. "…It had made a great impression on Tatiana, who cried a lot, and they both slept badly."[53] Three years later, she saw gunshot wounds close up when she trained to become a Red Cross nurse. Olga, her sister Tatiana, and her mother Tsarina Alexandra treated wounded soldiers at a hospital on the grounds of Tsarskoye Selo.

Olga was disdainful of her cousin Princess Irina of Russia's husband Felix Yussupov, the man who eventually murdered Rasputin in December 1916. Yussupov had taken advantage of a law permitting men who were only sons to avoid military service. He was in civilian dress at a time when many of the Romanov men and the wounded soldiers Olga cared for were fighting. "Felix is a 'downright civilian', dressed all in brown, walked to and fro about the room, searching in some bookcases with magazines and virtually doing nothing; an utterly unpleasant impression he makes – a man idling in such times", Olga wrote to her father, Tsar Nicholas, on 5 March 1915 after paying a visit to the Yussupovs.[54] She was also strongly patriotic. In July 1915, while discussing the wedding of an acquaintance with fellow nurses, Olga said she understood why the ancestry of the groom's German grandmother was being kept hidden. "Of course he has to conceal it", she burst out. "I quite understand him, she may perhaps be a real bloodthirsty German."[55] Olga's unthinking comments hurt her mother, who had been born in Germany, reported fellow nurse Valentina Ivanovna Chebotareva.[55] Nursing during the war provided Olga and her sister Tatiana with exposure to experiences they had not previously had. The girls enjoyed talking with fellow nurses at the hospital, women they would never have met if not for the war, and knew the names of their children and their family stories.[56] On one occasion, when a lady in waiting who usually picked up the girls from the hospital was detained and sent a carriage without an attendant, the two girls decided to go shopping in a store when they had a break. They ordered the carriage driver to stop in a shopping district and went into a store where they were not recognized because of their nursing uniforms. However, they discovered that they didn't know how to buy anything because they had never used money. The next day they asked Chebotareva how to go about purchasing an item from a store.[56] Yet other stories tell of a regular salary of nine dollars the girls received each month, and how they used it to purchase such items as perfume and notepaper.[57] They had also been shopping with their Aunt, Olga Alexandrovna[58] and Olga had visited shops on a trip to Germany with her sister Tatiana[59]

Olga cared for and pitied the soldiers she helped to treat. However, the stress of caring for wounded, dying men eventually also took its toll on the sensitive, moody Olga's nerves. Her sister Maria reported in a letter that Olga broke three panes of a window on a "caprice" with her umbrella on 5 September 1915.[60] On another occasion, she destroyed items in a cloakroom when she was "in a rage", according to the memoirs of Valentina Chebotareva. On 19 October 1915 she was assigned office work at the hospital because she was no longer able to bear the gore of the operating theater.[61] She was given arsenic injections in October 1915, at the time considered a treatment for depression or nervous disorders.[62] Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, one of her mother's ladies in waiting, recalled that Olga had to give up nursing and instead only supervised the hospital wards because she had "overtired herself" and became "nervous and anaemic."[63]

According to the accounts of courtiers, Olga knew the financial and political state of the country during the war and revolution. She reportedly also knew how much the Russian people disliked her mother and father. "She was by nature a thinker", remembered Gleb Botkin, the son of the family's physician, Yevgeny Botkin, "and as it later seemed to me, understood the general situation better than any member of her family, including even her parents. At least I had the impression that she had little illusions in regard to what the future held in store for them, and in consequence was often sad and worried."[13]

Captivity and death

The family were arrested during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and were imprisoned first at their home in Tsarskoye Selo and later at private residences in Tobolsk and Yekaterinburg, Siberia. "Darling, you must know how awful it all is", Olga wrote in a letter to a friend from Tobolsk.[64] During the early months of 1917, the children caught measles. Olga contracted pleurisy, as well.

Olga tried to draw comfort from her faith and her proximity to her family. To her "beloved mama", with whom she had sometimes had a difficult relationship, she wrote a poem in April 1917, while the family was still imprisoned at Tsarskoye Selo: "You are filled with anguish for the sufferings of others. And no one's grief has ever passed you by. You are relentless, only towards yourself, forever cold and pitiless. But if only you could look upon your own sadness from a distance, just once with a loving soul — Oh, how you would pity yourself, how sadly you would weep."[65] In another letter from Tobolsk, Olga wrote: "Father asks to … remember that the evil which is now in the world will become yet more powerful, and that it is not evil which conquers evil, but only love …"[66]

A poem copied into one of her notebooks prays for patience and the ability to forgive her enemies:

- "Send us, Lord, the patience, in this year of stormy, gloom-filled days, to suffer popular oppression, and the tortures of our hangmen. Give us strength, oh Lord of justice, Our neighbor's evil to forgive, And the Cross so heavy and bloody, with Your humility to meet, In days when enemies rob us, To bear the shame and humiliation, Christ our Savior, help us. Ruler of the world, God of the universe, Bless us with prayer and give our humble soul rest in this unbearable, dreadful hour. At the threshold of the grave, breathe into the lips of Your slaves inhuman strength — to pray meekly for our enemies."[67]

Also found with Olga's effects, reflecting her own determination to remain faithful to the father she adored, was Edmond Rostand's L'Aiglon, the story of Napoleon Bonaparte's son, who remained loyal to his deposed father until the end of his life.[68]

There was one report that her father gave Olga a small revolver, which she concealed in a boot while in captivity at Tsarskoe Selo and at Tobolsk. Colonel Eugene Kobylynsky, their sympathetic jailer, pleaded with the grand duchess to surrender her revolver before she, her sisters, and brother were transferred to Yekaterinburg. Olga reluctantly gave up her gun and was left unarmed.[69]

The family had been briefly separated in April 1918 when the Bolsheviks moved Nicholas, Alexandra, and Maria to Yekaterinburg. Alexei and the three other young women remained behind because Alexei had suffered another attack of hemophilia. The Empress chose Maria to accompany her because "Olga's spirits were too low" and level-headed Tatiana was needed to take care of Alexei.[70] In May 1918 the remaining children and servants boarded the ship Rus that ferried them from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg. Aboard ship, Olga was distressed when she saw one of the guards slip from a ladder and injure his foot. She ran to the man and explained that she had been a nurse during the war and wanted to look at his foot. He refused her offer of treatment. All through the afternoon, Olga fretted over the guard, whom she called "her poor fellow."[71] At Tobolsk Olga and her sisters had sewn jewels into their clothing in hopes of hiding them from the Bolsheviks, since Alexandra had written to warn them that upon arrival in Ekaterinburg, she, Nicholas and Maria had been aggressively searched and belongings confiscated.[72]

Pierre Gilliard later recalled his last sight of the imperial children at Yekaterinburg:

"The sailor Nagorny, who attended to Alexei Nikolaevitch, passed my window carrying the sick boy in his arms, behind him came the Grand Duchesses loaded with valises and small personal belongings. I tried to get out, but was roughly pushed back into the carriage by the sentry. I came back to the window. Tatiana Nikolayevna came last carrying her little dog and struggling to drag a heavy brown valise. It was raining and I saw her feet sink into the mud at every step. Nagorny tried to come to her assistance; he was roughly pushed back by one of the commissars …"[73]

At the Ipatiev House, Olga and her sisters were eventually required to do their own laundry and learned how to make bread. The girls took turns keeping Alexandra company and amusing Alexei, who was still confined to bed and suffering from pain after his latest injury. Olga was reportedly deeply depressed and lost a great deal of weight during her final months. "She was thin, pale, and looked very sick", recalled one of the guards, Alexander Strekotin, in his memoirs. "She took few walks in the garden, and spent most of her time with her brother." Another guard recalled that the few times she did walk outside, she stood there "gazing sadly into the distance, making it easy to read her emotions."[74] Later, Olga appeared angry with her younger sister Maria for being too friendly to the guards, reported Strekotin.[75] After late June, when a new command was installed, the family was forbidden from fraternizing with the guards and the conditions of their imprisonment became even more stringent.

On 14 July 1918, local priests at Yekaterinburg conducted a private church service for the family and reported that Olga and her family, contrary to custom, fell on their knees during the prayer for the dead.[76] The following day, on 15 July, Olga and her sisters appeared in good spirits as they joked with one another and moved the beds in their room so visiting cleaning women could scrub the floor. They got down on their hands and knees to help the women and whispered to them when the guards weren't looking. All four young women wore long black skirts and white silk blouses, the same clothing they had worn the previous day. Their short hair was "tumbled and disorderly." They told the women how much they enjoyed physical exertion and wished there was more of it for them to do in the Ipatiev House. Olga appeared sickly.[77] As the family was eating dinner that night, Yakov Yurovsky, the head of the detachment, came in and announced that the family's kitchen boy and Alexei's playmate, 14-year-old Leonid Sednev, must gather his things and go to a family member. The boy had actually been sent to a hotel across the street because the guards did not want to kill him along with the rest of the Romanov party. The family, unaware of the plan to kill them, was upset and unsettled by Sednev's absence. Dr. Eugene Botkin and Tatiana went that evening to Yurovsky's office, for what was to be the last time, to ask for the return of the kitchen boy who kept Alexei amused during the long hours of captivity. Yurovsky placated them by telling them the boy would return soon, but the family was unconvinced.[78]

Late that night, on the night of 16 July, the family was awakened and told to come down to the lower level of the house because there was unrest in the town at large and they would have to be moved for their own safety. The family emerged from their rooms carrying pillows, bags, and other items to make Alexandra and Alexei comfortable. The family paused and crossed themselves when they saw the stuffed mother bear and cubs that stood on the landing, perhaps as a sign of respect for the dead. Nicholas told the servants and family "Well, we're going to get out of this place." They asked questions of the guards but did not appear to suspect they were going to be killed. Yurovsky, who had been a professional photographer, directed the family to take different positions as a photographer might. Alexandra, who had complained about the lack of chairs for herself and Alexei, sat to her son's left. The Tsar stood behind Alexei, Dr. Botkin stood to the Tsar's right, Olga and her sisters stood behind Alexandra along with the servants. They were left for approximately half an hour while further preparations were made. The group said little during this time, but Alexandra whispered to the girls in English, violating the guard's rules that they must speak in Russian. Yurovsky came in, ordered them to stand, and read the sentence of execution. Olga and her mother attempted to make the sign of the cross and the rest of the family had time only to utter a few incoherent sounds of shock or protest before the death squad under Yurovsky's command began shooting. It was the early hours of 17 July 1918.[79]

The initial round of gunfire killed only the Tsar, the Empress and two male servants, and wounded Grand Duchess Maria, Dr Botkin and the Empress' maidservant, Demidova. At that point the gunmen had to leave the room because of smoke and toxic fumes from their guns and plaster dust their bullets had released from the walls. After allowing the haze to clear for several minutes, the gunmen returned. Dr Botkin was killed, and a gunman named Ermakov repeatedly tried to shoot Tsarevich Alexei, but failed because jewels sewn into the boy's clothes shielded him. Ermakov tried to stab Alexei with a bayonet but failed again, and finally Yurovsky fired two shots into the boy's head. Yurovsky and Ermakov approached Olga and Tatiana, who were crouched against the room's rear wall, clinging to each other and screaming for their mother. Ermakov stabbed both young women with his 8-inch bayonet, but had difficulty penetrating their torsos because of the jewels that had been sewn into their chemises. The sisters tried to stand, but Tatiana was killed instantly when Yurovsky shot her in the back of her head. A moment later, Olga too died when Ermakov shot her in the jaw.[80][81]

For decades (until all the bodies were found and identified, see below) conspiracy theorists suggested that one or more of the family somehow survived the slaughter. Several people claimed to be surviving members of the Romanov family following the assassinations. A woman named Marga Boodts claimed to be Grand Duchess Olga. Boodts lived in a villa on Lake Como in Italy and it was claimed that she was supported by the former kaiser, Wilhelm II and by Pope Pius XII. Prince Sigismund of Prussia, son of Alexandra's sister, Irene, said he accepted her as Olga, and Sigismund also supported Anastasia claimant Anna Anderson.[82] His mother, Irene, did not believe either woman. Michael Goleniewski, an Alexei pretender, even claimed that the entire family had escaped.[83] Most historians discounted the claims and consistently believed that Olga died with her family.[84]

Romanov graves and DNA proof

Remains later identified through DNA testing as the Romanovs and their servants were discovered in the woods outside Yekaterinburg in 1991. Two bodies, Alexei and one of his sisters, generally thought to be either Maria or Anastasia, were missing. On 23 August 2007, a Russian archaeologist announced the discovery of two burned, partial skeletons at a bonfire site near Yekaterinburg that appeared to match the site described in Yurovsky's memoirs. The archaeologists said the bones are from a boy who was roughly between the ages of ten and thirteen years at the time of his death and of a young woman who was roughly between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three years old. Anastasia was seventeen years, one month old at the time of the assassination, while her sister Maria was nineteen years, one month old and her brother Alexei was two weeks shy of his fourteenth birthday. Olga and Tatiana were twenty-two and twenty-one years old at the time of the assassination. Along with the remains of the two bodies, archaeologists found "shards of a container of sulfuric acid, nails, metal strips from a wooden box, and bullets of various caliber." The bones were found using metal detectors and metal rods as probes.[85]

Preliminary testing indicated a "high degree of probability" that the remains belong to the Tsarevich Alexei and to one of his sisters, Russian forensic scientists announced on 22 January 2008.[86] The Yekaterinburg region's chief forensic expert Nikolai Nevolin indicated the results would be compared against those obtained by foreign experts.[87] On 30 April 2008, Russian forensic scientists announced that DNA testing confirms that the remains belong to the Tsarevich Alexei and to one of his sisters.[88] In March 2009, Dr. Michael Coble of the US Armed Forces DNA Identification Lab published the final, peer reviewed results of the tests on the 2007 remains, comparing them with the 1991 remains, concluding the entire family died together in 1918. Russian and Austrian scientists got the same results.[89] This finding confirms that all of the Tsar's family were accounted for.

Sainthood

- For more information, see Romanov sainthood

In 2000, Olga and her family were canonized as passion bearers by the Russian Orthodox Church. The family had previously been canonized in 1981 by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad as holy martyrs.

The bodies of Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra, and three of their daughters were finally interred at St. Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg on 17 July 1998, eighty years after they were murdered.[90]

Ancestry

Notes

- Because Russia continued to use the Julian calendar in 1900 and later, her birthday ended up being celebrated on 16 November new style starting in 1900

- Zeepvat, p. xiv

- Massie (1967), p. 135

- Eagar, Margaret (1906). "Six Years at the Russian Court". alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- Massie (1967), p. 132

- Gilliard, Pierre. "Thirteen Years at the Russian Court". alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- Massie (1967), p. 133

- Vyrubova, Anna. "Memories of the Russian Court". alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- Radzinsky (1992), p. 358

- Bokhanov et al., p. 124

- King and Wilson, p. 47

- Radzinsky, p. 116

- King and Wilson, p. 46

- King and Wilson, p. 45

- Maylunas and Mironenko, pp. 318–319.

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 319

- Radzinsky, The Last Tsar, p. 116

- Maylunas and Mironkenko, p. 320

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 352

- A. A. Mossolov. "At the Court of the Last Tsar". Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- Vorres, p. 115

- Zeepvat, p. 175

- Massie (1967), pp. 199–200

- Massie (1967), p. 208

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 330

- Radzinsky (2000), pp. 129–130.

- Hugo Mager, Elizabeth: Grand Duchess of Russia, Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc., 1998, ISBN 0-7867-0678-3

- Christopher, Kurth, and Radzinsky, p. 115.

- Christopher, Kurth, and Radzinsky, p. 116

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 489

- Radzinsky, The Rasputin File, p. 481

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 507

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 511

- GARF673-1-8 Diary of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna 11.12.1916-15.03.1917

- Gregory P. Tschebotarioff, Russia: My Native Land: A U.S. engineer reminisces and looks at the present, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1964, p. 61

- Massie, "Final Chapter" p. 8

- Massie, p. 136

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 370

- Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, pp. 132–133

- Dehn, Lili (1922). "The Real Tsaritsa". ISBN 5-300-02285-3 Retrieved on 22 February 2007

- Bokhanov et al., p. 123

- Massie (1967), p. 179

- Radzinsky (2000), pp. 181–182

- Sullivan, p. 281

- Sullivan, p. 280

- Massie, p. 252

- Zeepvat, p. 110

- "'Olga Nicholaievna and Mitia', a discussion with translations from V.I. Chebotareva's diary". alexanderpalace.org. 2006. Archived from the original on 16 February 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- Maylunas and Mironenko, pp. 491–492

- Azar, Helen. "The Diary of Olga Romanov: Royal Witness to the Russian Revolution." Westholme Publishing, 2013.

- Zeepvat, p. 224

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 453

- Maylunas and Mironenko, p. 344.

- Bokhanov et al., p. 240

- Tschebotarioff, p. 57

- Tschebotarioff, p. 60

- Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra, p. 127

- Vorres

- Anna Vyrubova, "Memories of the Russian Court", Chapter 5.

- "Extracts of Letters from Maria to her Father". alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- "Olga Breaking Windows". alexanderpalace.org. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- "Letters of the Tsaritsa to the Tsar – October 1915". alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- Buxhoeveden, Baroness Sophie. "The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna: Empress of Russia". alexanderpalace.org. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- Kurth, p. xii

- Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1917). "To My Beloved Mama". livadia.org. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- Christopher, Kurth, and Radzinsky, p. 221.

- Radzinsky, p. 359

- Radzinsky (1992), p. 359

- ""Olga Armed", at thread at alexanderpalace.org". alexanderpalace.org. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- Christopher, Kurth, and Radzinsky, p. 180

- King and Wilson, p. 143

- Robert Wilton, "Last Days of the Romanovs", p.30

- Bokhanov et al., p. 310

- King and Wilson, p. 238

- King and Wilson, p. 246

- King and Wilson, p. 276

- Rappaport, The Last Days of the Romanovs, p. 172

- Rappaport, The Last Days of the Romanovs, p. 180.

- Rappaport, The Last Days of the Romanovs, pp. 184–189

- King and Wilson, p. 303

- Rappaport, p. 190.

- Welch, Frances, "A Romanov Fantasy", Norton publishing, 2007, p. 218

- Massie p. 151

- Massie, Robert K. The Romanovs: The Final Chapter, Random House, 1995, ISBN 0-394-58048-6, p. 147

- Gutterman, Steve (23 August 2007). "Bones turn up in hunt for last czar's son". Associated Press. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- "Suspected remains of tsar's children still being studied". Interfax. 22 January 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- "Remains found in Urals likely belong to Tsar's children". RIA Novosti. 22 January 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- Eckel, Mike (2008). "DNA confirms IDs of czar's children". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Coble Michael D (2009). "Mystery Solved: The Identification of the Two Missing Romanov Children Using DNA Analysis". PLoS ONE. 4: e4838. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004838. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- Shevchenko, Maxim (31 May 2000). "The Glorification of the Royal Family". Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Archived from the original on 24 August 2005. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- Alexander II, Emperor of Russia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Alexander III, Emperor of Russia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Zeepvat, Charlotte. Heiligenberg: Our Ardently Loved Hill. Published in Royalty Digest. No 49. July 1995.

- "Christian IX". The Danish Monarchy. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Vammen, Tinne. "Louise (1817–1898)". Dansk Biografisk Leksikon (in Danish).

- Willis, Daniel A. (2002). The Descendants of King George I of Great Britain. Clearfield Company. p. 717. ISBN 0-8063-5172-1.

- Gelardi, Julia P. (1 April 2007). Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria. St. Martin's Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781429904551. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Ludwig Clemm (1959), "Elisabeth", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 444–445; (full text online)

- Louda, Jiří; Maclagan, Michael (1999). Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. London: Little, Brown. p. 34. ISBN 1-85605-469-1.

Sources

- Azar, Helen. "The Diary of Olga Romanov: Royal Witness to the Russian Revolution. Westholme Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1594161773

- Bokhanov, Alexander, Knodt, Dr. Manfred, Oustimenko, Vladimir, Peregudova, Zinaida, Tyutyunnik, Lyubov; trans. Lyudmila Xenofontova. The Romanovs: Love, Power, and Tragedy, Leppi Publications, 1993, ISBN 0-9521644-0-X

- Buxhoeveden, Baroness Sophie. The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna

- Christopher, Peter, Kurth, Peter, and Radzinsky, Edvard. Tsar: The Lost World of Nicholas and Alexandra ISBN 0-316-50787-3

- Gilliard Pierre, Thirteen Years at the Russian Court

- King, Greg, and Wilson, Penny. The Fate of the Romanovs, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2003, ISBN 0-471-20768-3

- Kurth, Peter. Anastasia: The Riddle of Anna Anderson, Back Bay Books, 1983, ISBN 0-316-50717-2

- Massie, Robert K. Nicholas and Alexandra, Dell Publishing Co., 1967, ISBN 0-440-16358-7

- idem. The Romanovs: The Final Chapter, Random House, 1995, ISBN 0-394-58048-6

- Maylunas, Andrei, and Mironenko, Sergei, eds.; Galy, Darya, translator. A Lifelong Passion: Nicholas and Alexandra: Their Own Story, Doubleday, 1997 ISBN 0-385-48673-1

- Rappaport, Helen. The Last Days of the Romanovs. St. Martin's Griffin, 2008. ISBN 978-0-312-60347-2

- Radzinsky, Edvard. The Last Tsar, Doubleday, 1992, ISBN 0-385-42371-3

- idem. The Rasputin File, Doubleday, 2000, ISBN 0-385-48909-9

- Sullivan, Michael John. A Fatal Passion: The Story of the Uncrowned Last Empress of Russia, Random House, 1997, ISBN 0-679-42400-8

- Tschebotarioff, Gregory P. Russia: My Native Land: A U.S. engineer reminisces and looks at the present, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1964, ASIN 64-21632

- Vorres, Ian. The Last Grand Duchess, 1965, ASIN B0007E0JK0

- Wilton, Robert "The Last Days of the Romanovs" 1920

- Zeepvat, Charlotte. The Camera and the Tsars: A Romanov Family Album, Sutton Publishing 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3049-7

Further reading

- Azar, Helen. "The Diary of Olga Romanov: Royal Witness to the Russian Revolution." Westholme Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1594161773

- Fleming, Candace. "The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion, and the Fall of Imperial Russia." Schwartz & Wade, 2014. ISBN 978-0375867828

- Rappaport, Helen. "The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra." St. Martin's Griffin, 2014. ISBN 978-1250067456

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olga Nikolaevna of Russia. |

- "Olishka's journal"

- "Olga's scrapbook"

- Biography at alexanderpalace.org

- FrozenTears.org A media library of the last Imperial Family.

- Hemophilia A (Factor VIII Deficiency)

- The Glorification of the Royal Family