Grigori Rasputin

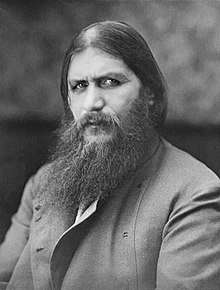

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (/ræˈspjuːtɪn/; Russian: Григорий Ефимович Распутин [ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲɪj jɪˈfʲiməvʲɪtɕ rɐˈsputʲɪn]; 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 – 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia, and gained considerable influence in late imperial Russia.

Grigori Rasputin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Григорий Ефимович Распутин |

| Church | Russian Orthodox Church |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin |

| Born | 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 Pokrovskoye, Tyumensky Uyezd, Tobolsk Governorate (Siberia), Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916 (aged 47) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Parents |

|

| Spouse | Praskovya Fedorovna Dubrovina ( m. 1887) |

| Children |

|

Rasputin was born to a peasant family in the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye in the Tyumensky Uyezd of Tobolsk Governorate (now Yarkovsky District of Tyumen Oblast). He had a religious conversion experience after taking a pilgrimage to a monastery in 1897. He has been described as a monk or as a "strannik" (wanderer or pilgrim), though he held no official position in the Russian Orthodox Church. He traveled to St. Petersburg in 1903 or the winter of 1904–1905, where he captivated some church and social leaders. He became a society figure and met Emperor Nicholas and Empress Alexandra in November 1905.

In late 1906, Rasputin began acting as a healer for the imperial couple's only son, Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia. He was a divisive figure at court, seen by some Russians as a mystic, visionary, and prophet, and by others as a religious charlatan. The high point of Rasputin's power was in 1915 when Nicholas II left St. Petersburg to oversee Russian armies fighting World War I, increasing both Alexandra and Rasputin's influence. Russian defeats mounted during the war, however, and both Rasputin and Alexandra became increasingly unpopular. In the early morning of 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916, Rasputin was assassinated by a group of conservative noblemen who opposed his influence over Alexandra and Nicholas.

Historians often suggest that Rasputin's terrible reputation helped discredit the tsarist government and thus helped precipitate the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty which happened a few weeks after he was assassinated. Accounts of his life and influence were often based on hearsay and rumor.

Early life

Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of Pokrovskoye, along the Tura River in the Tobolsk Governorate (now Tyumen Oblast) in Siberia.[1] According to official records, he was born on 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 and christened the following day.[2] He was named for St. Gregory of Nyssa, whose feast was celebrated on 10 January.[3]

There are few records of Rasputin's parents. His father, Yefim,[3] was a peasant farmer and church elder who had been born in Pokrovskoye in 1842, and married Rasputin's mother, Anna Parshukova, in 1863. Yefim also worked as a government courier, ferrying people and goods between Tobolsk and Tyumen[4][3] The couple had seven other children, all of whom died in infancy and early childhood; there may have been a ninth child, Feodosiya. According to historian Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin was certainly close to Feodosiya and was godfather to her children, but "the records that have survived do not permit us to say more than that".[4]

According to historian Douglas Smith, Rasputin's youth and early adulthood are "a black hole about which we know almost nothing", though the lack of reliable sources and information did not stop others from fabricating stories about his parents and his youth after Rasputin's rise to fame.[5] Historians agree, however, that like most Siberian peasants, including his mother and father, Rasputin was not formally educated and remained illiterate well into his early adulthood.[3][6] Local archival records suggest that he had a somewhat unruly youth—possibly involving drinking, small thefts, and disrespect for local authorities—but contain no evidence of his being charged with stealing horses, blasphemy, or bearing false witness, all major crimes that he was later rumored to have committed as a young man.[7]

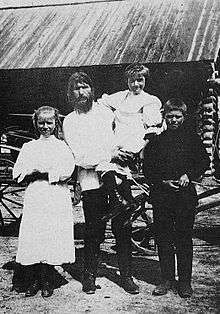

In 1886, Rasputin travelled to Abalak, Russia, some 250 km east-northeast of Tyumen and 2,800 km east of Moscow, where he met a peasant girl named Praskovya Dubrovina. After a courtship of several months, they married in February 1887. Praskovya remained in Pokrovskoye throughout Rasputin's later travels and rise to prominence and remained devoted to him until his death. The couple had seven children, though only three survived to adulthood: Dmitry (b. 1895), Maria (b. 1898), and Varvara (b. 1900).[8]

Religious conversion

In 1897, Rasputin developed a renewed interest in religion and left Pokrovskoye to go on a pilgrimage. His reasons for doing so are unclear; according to some sources, Rasputin left the village to escape punishment for his role in a horse theft.[9] Other sources suggest that he had a vision—either of the Virgin Mary or of St. Simeon of Verkhoturye—while still others suggest that Rasputin's pilgrimage was inspired by his interactions with a young theological student, Melity Zaborovsky.[10] Whatever his reasons, Rasputin's departure was a radical life change: he was twenty-eight, had been married ten years, and had an infant son with another child on the way. According to Douglas Smith, his decision "could only have been occasioned by some sort of emotional or spiritual crisis".[11]

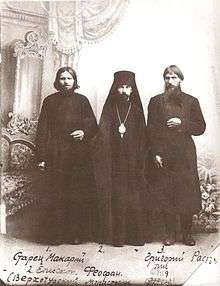

Rasputin had undertaken earlier, shorter pilgrimages to the Holy Znamensky Monastery at Abalak and to Tobolsk's cathedral, but his visit to the St. Nicholas Monastery at Verkhoturye in 1897 was transformative.[12] There, he met and was "profoundly humbled" by a starets (elder) known as Makary. Rasputin may have spent several months at Verkhoturye, and it was perhaps here that he learned to read and write, but he later complained about the monastery, claiming that some of the monks engaged in homosexuality and criticizing monastic life as too coercive.[13] He returned to Pokrovskoye a changed man, looking disheveled and behaving differently than he had before. He became a vegetarian, swore off alcohol, and prayed and sang much more fervently than he had in the past.[14]

Rasputin spent the years that followed living as a Strannik (a holy wanderer, or pilgrim), leaving Pokrovskoye for months or even years at a time to wander the country and visited a variety of holy sites.[15] It is possible that Rasputin wandered as far as Mount Athos—the center of Eastern Orthodox monastic life—in 1900.[16]

By the early 1900s, Rasputin had developed a small circle of followers, primarily family members and other local peasants, who prayed with him on Sundays and other holy days when he was in Pokrovskoye. Building a makeshift chapel in Efim's root cellar—Rasputin was still living within his father's household at the time—the group held secret prayer meetings there. These meetings were the subject of some suspicion and hostility from the village priest and other villagers. It was rumored that female followers were ceremonially washing him before each meeting, that the group sang strange songs that the villagers had not heard before, and even that Rasputin had joined the Khlysty, a religious sect whose ecstatic rituals were rumored to include self-flagellation and sexual orgies.[17][18] According to historian Joseph Fuhrmann, however, "repeated investigations failed to establish that Rasputin was ever a member of the sect", and rumors that he was a Khlyst appear to have been unfounded.[19]

Rise to prominence

Word of Rasputin's activity and charisma began to spread in Siberia during the early 1900s.[17] At some point during 1904 or 1905, he traveled to the city of Kazan, where he acquired a reputation as a wise and perceptive starets, or holy man, who could help people resolve their spiritual crises and anxieties.[20] Despite rumors that Rasputin was having sex with some of his female followers,[21] he made a favorable impression on the father superior of the Seven Lakes Monastery outside Kazan, as well as a local church officials Archimandrite Andrei and Bishop Chrysthanos, who gave him a letter of recommendation to Bishop Sergei, the rector of the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, and arranged for him to travel to St. Petersburg.[22][23][24]

Upon meeting Sergei at the Nevsky Monastery, Rasputin was introduced to church leaders, including Archimandrite Theofan, who was the inspector of the theological seminary, was well-connected in St. Petersburg society, and later served as confessor to the tsar and his wife.[25][26] Theofan was so impressed with Rasputin that he invited him to stay in his home. Theofan became one of Rasputin's most important and influential friends in St. Petersburg,[25] and gained him entry to many of the influential salons where the aristocracy gathered for religious discussions. It was through these meetings that Rasputin attracted some of his early and influential followers - many of whom would later turn against him.[27]

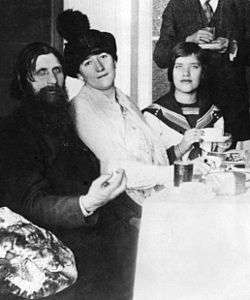

Alternative religious movements such as spiritualism and theosophy had become popular among the city's aristocracy before Rasputin's arrival in St. Petersburg, and many of the aristocracy were intensely curious about the occult and the supernatural.[28] Rasputin's ideas and "stranger manners" made him the subject of intense curiosity among St Petersburg's elite, who according to historian Joseph Fuhrmann were "bored, cynical, and seeking new experiences" during this period.[25] His appeal may have been enhanced by the fact that he was also a native Russian, unlike other self-described "holy men" such as Nizier Anthelme Philippe and Gérard Encausse, who had previously been popular in St Petersburg.[26]

According to Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg for only a few months on his first visit and returned to Pokrovskoye in the fall of 1903.[29] Historian Douglas Smith, however, argues that it is impossible to know whether Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg or returned to Pokrovskoye at some point between his first arrival there and 1905.[30] Regardless, by 1905 Rasputin had formed friendships with several members of the aristocracy, including the "Black Princesses", Militsa and Anastasia of Montenegro, who had married the tsar's cousins (Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich and Prince George Maximilianovich Romanowsky), and were instrumental in introducing Rasputin to the tsar and his family.[26][31]

Rasputin first met the tsar on 1 November 1905, at the Peterhof Palace. The tsar recorded the event in his diary, writing that he and Alexandra had "made the acquaintance of a man of God – Grigory, from Tobolsk province".[30] Rasputin returned to Pokrovskoye shortly after their first meeting and did not return to St. Petersburg until July 1906.[32] On his return, Rasputin sent Nicholas a telegram asking to present the tsar with an icon of Simeon of Verkhoturye. He met with Nicholas and Alexandra on 18 July and again in October, when he first met their children.[33] At some point, the royal family became convinced that Rasputin possessed the power to heal Alexei, but historians disagree over when: according to Orlando Figes, Rasputin was first introduced to the tsar and tsarina as a healer who could help their son in November 1905,[34] while Joseph Fuhrmann has speculated that it was in October 1906 that Rasputin was first asked to pray for the health of Alexei.[35]

Healer to Alexei

Much of Rasputin's influence with the royal family stemmed from the belief by Alexandra and others that he had eased the pain and stopped the bleeding of the tsarevich—who suffered from hemophilia—on several occasions. According to historian Marc Ferro, the tsarina had a "passionate attachment" to Rasputin as a result of her belief that he could heal her son's affliction.[36] Harold Shukman wrote that Rasputin became "an indispensable member of the royal entourage" as a result.[37] It is unclear when Rasputin first learned of Alexei's hemophilia, or when he first acted as a healer for Alexei. He may have been aware of Alexei's condition as early as October 1906,[35] and was summoned by Alexandra to pray for Alexei when he had an internal hemorrhage in the spring of 1907. Alexei recovered the next morning.[38] Rasputin had been rumored to be capable of faith-healing since his arrival in St. Petersburg,[39] and the tsarina's friend Anna Vyrubova became convinced that Rasputin had miraculous powers shortly thereafter. Vyrubova would become one of Rasputin's most influential advocates.[40][41]

During the summer of 1912, Alexei developed a hemorrhage in his thigh and groin after a jolting carriage ride near the royal hunting grounds at Spala, which caused a large hematoma.[42] In severe pain and delirious with fever, the tsarevich appeared to be close to death.[43] In desperation, the tsarina asked Vyrubova to send Rasputin (who was in Siberia) a telegram, asking him to pray for Alexei.[44] Rasputin wrote back quickly, telling the tsarina that "God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much."[44] The next morning, Alexei's condition was unchanged, but Alexandra was encouraged by the message and regained some hope that Alexei would survive. Alexei's bleeding stopped the following day.[44]

Historian Robert K. Massie has calls Alexei's recovery "one of the most mysterious episodes of the whole Rasputin legend".[44] The cause of his recovery is unclear: Massie speculated that Rasputin's suggestion not to let doctors disturb Alexei had aided his recovery by allowing him to rest and heal, or that his message may have aided Alexei's recovery by calming Alexandra and reducing the emotional stress on Alexei.[45] Alexandra, however, believed that Rasputin had performed a miracle, and concluded that he was essential to Alexei's survival.[46] Some writers and historians, such as Ferro, claim that Rasputin stopped Alexei's bleeding on other occasions through hypnosis.[36]

Controversy

The royal family's belief that Rasputin possessed the power to heal Alexei brought him considerable status and power at court.[47] The tsar appointed Rasputin his lampadnik (lamplighter) who was charged with keeping the lamps lit that burned in front of religious icons in the palace, and he thus had regular access to the palace and royal family.[48] By December 1906, Rasputin had become close enough to the royal family to ask a special favor of the tsar: that he be permitted to change his surname to Rasputin-Novyi (Rasputin-New). Nicholas granted the request and the name change was speedily processed, suggesting that the tsar viewed and treated Rasputin favorably at that time.[35] Rasputin used his status and power to full effect, accepting bribes and sexual favors from admirers[47] and working diligently to expand his influence.

Rasputin soon became a controversial figure; he was accused by his enemies of religious heresy and rape, was suspected of exerting undue political influence over the tsar, and was even rumored to be having an affair with the tsarina.[49] Opposition to Rasputin's influence grew within the church. In 1907, the local clergy in Pokrovskoye denounced Rasputin as a heretic, and the Bishop of Tobolsk launched an inquest into his activities, accusing him of "spreading false, Khlyst-like doctrines."[50] In St Petersburg, Rasputin faced opposition from even more prominent critics, including prime minister Peter Stolypin and the Okhrana, the Tsar's secret police.[51] Having ordered an investigation into Rasputin's activities, Stolypin confronted the Tsar about him, but did not succeed in convincing him to reign in Rasputin's influence, and was unsuccessful in an attempt to bar Rasputin from St Petersburg.[52] In 1909 Kehioniya Berlatskaya, who had been one of Rasputin's early supporters in St Petersburg, accused him of rape. She went to Theofan for aid, and the incident helped to convince Theofan that Rasputin was a danger to the monarchy.[53] Rumors that Rasputin had assaulted female followers and behaved inappropriately on visits to the royal family – and particularly with the Tsar's teenage daughters Olga and Tatyana – multiplied, and were reported widely in the press after March of 1910.[54][55]

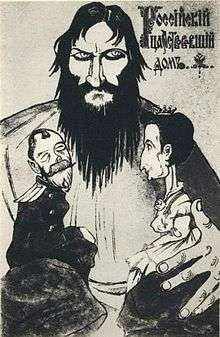

World War I, the disappearance of feudalism, and a meddling government bureaucracy all contributed to Russia's declining economy at a very rapid rate. Many laid the blame with Alexandra and with Rasputin, because of his influence over her. One outspoken member of the Duma, Vladimir Purishkevich stated in November 1916 that the tsar's ministers had "been turned into marionettes, marionettes whose threads have been taken firmly in hand by Rasputin and the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna – the evil genius of Russia and the Tsarina… who has remained a German on the Russian throne and alien to the country and its people."[56]

Assassination attempt

On 12 July [O.S. 29 June] 1914 a 33-year-old peasant woman named Chionya Guseva attempted to assassinate Rasputin by stabbing him in the stomach outside his home in Pokrovskoye.[57] Rasputin was seriously wounded, and for a time it was not clear that he would survive.[58] After surgery[59] and some time in a hospital in Tyumen,[60] he recovered.

Guseva was a follower of Iliodor, a former priest who had supported Rasputin before denouncing his sexual escapades and self-aggrandizement in December 1911.[61][62] A radical conservative and anti-semite, Iliodor had been part of a group of establishment figures who had attempted to drive a wedge between the royal family and Rasputin in 1911. When this effort failed, Iliodor was banished from Saint Petersburg and was ultimately defrocked.[61][63] Guseva claimed to have acted alone, having read about Rasputin in the newspapers and believing him to be a "false prophet and even an Antichrist".[64] Both the police and Rasputin, however, believed that Iliodor had played some role in the attempt on Rasputin's life.[61] Iliodor fled the country before he could be questioned about the assassination attempt, and Guseva was found to be not responsible for her actions by reason of insanity.[61]

Death

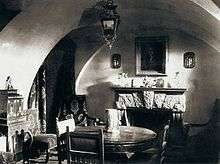

A group of nobles led by Prince Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and right-wing politician Vladimir Purishkevich decided that Rasputin's influence over the tsarina had made him a threat to the empire, and they concocted a plan in December 1916 to kill him, apparently by luring him to the Yusupovs' Moika Palace.[65][66]

Rasputin was murdered during the early morning on 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916 at the home of Felix Yusupov. He died of three gunshot wounds, one of which was a close-range shot to his forehead. Little is certain about his death beyond this, and the circumstances of his death have been the subject of considerable speculation. According to historian Douglas Smith, "what really happened at the Yusupov home on 17 December will never be known".[67] The story that Yusupov recounted in his memoirs, however, has become the most frequently told version of events.[68]

Yusupov claimed that he invited Rasputin to his home shortly after midnight and ushered him into the basement. Yusupov offered Rasputin tea and cakes which had been laced with cyanide. Rasputin initially refused the cakes but then began to eat them and, to Yusupov's surprise, he did not appear to be affected by the poison.[69] Rasputin then asked for some Madeira wine (which had also been poisoned) and drank three glasses, but still showed no sign of distress. At around 2:30 am, Yusupov excused himself to go upstairs, where his fellow conspirators were waiting. He took a revolver from Dmitry Pavlovich, then returned to the basement and told Rasputin that he'd "better look at the crucifix and say a prayer", referring to a crucifix in the room, then shot him once in the chest. The conspirators then drove to Rasputin's apartment, with Sukhotin wearing Rasputin's coat and hat in an attempt to make it look as though Rasputin had returned home that night.[70] They then returned to the Moika Palace and Yusupov went back to the basement to ensure that Rasputin was dead.[71] Suddenly, Rasputin leapt up and attacked Yusupov, who freed himself with some effort and fled upstairs. Rasputin followed and made it into the palace's courtyard before being shot by Purishkevich and collapsing into a snowbank. The conspirators then wrapped his body in cloth, drove it to the Petrovsky Bridge, and dropped it into the Malaya Nevka River.[72]

Aftermath

News of Rasputin's murder spread quickly, even before his body was found. According to Douglas Smith, Purishkevich spoke openly about Rasputin's murder to two soldiers and to a policeman who was investigating reports of shots shortly after the event, but he urged them not to tell anyone else.[73] An investigation was launched the next morning.[74] The Stock Exchange Gazette ran a report of Rasputin's death "after a party in one of the most aristocratic homes in the center of the city" on the afternoon of 30 December [O.S. 17 December] 1916.

Two workmen noticed blood on the railing of the Petrovsky Bridge and found a boot on the ice below, and police began searching the area.[75] Rasputin's body was found under the river ice on 1 January (O.S. 19 December) approximately 200 meters downstream from the bridge.[76] Dr. Dmitry Kosorotov, the city's senior autopsy surgeon, conducted an autopsy. Kosorotov's report was lost, but he later stated that Rasputin's body had shown signs of severe trauma, including three gunshot wounds (one at close range to the forehead), a slice wound to his left side, and many other injuries, many of which Kosorotov felt had been sustained post-mortem.[77] Kosorotov found a single bullet in Rasputin's body but stated that it was too badly deformed and of a type too widely used to trace. He found no evidence that Rasputin had been poisoned.[78] According to both Douglas Smith and Joseph Fuhrmann, Kosorotov found no water in Rasputin's lungs, and reports were incorrect that Rasputin had been thrown into the water alive.[79][80] Some later accounts claimed that Rasputin's penis had been severed, but Kosorotov found his genitals intact.[78]

Rasputin was buried on 2 January (O.S. 21 December) at a small church that Anna Vyrubova had been building at Tsarskoye Selo. The funeral was attended only by the imperial family and a few of their intimates. Rasputin's wife, mistress, and children were not invited,[81] although his daughters met with the imperial family at Vyrubova's home later that day.[82] His body was exhumed and burned by a detachment of soldiers shortly after the tsar abdicated the throne in March 1917,[81] so that his grave would not become a rallying point for supporters of the old regime.[83]

Theory of British involvement

Some writers have suggested that agents of the British Secret Intelligence Service (BSIS) were involved in Rasputin's assassination.[84] According to this theory, British agents were concerned that Rasputin was urging the tsar to make a separate peace with Germany, which would allow Germany to concentrate its military efforts on the Western Front.[84] There are several variants of this theory, but they generally suggest that British intelligence agents were directly involved in planning and carrying out the assassination under the command of Samuel Hoare and Oswald Rayner, who had attended Oxford University with Yusopov,[85][86] or that Rayner had personally shot Rasputin.[87] However, historians do not seriously consider this theory. According to historian Douglas Smith, "there is no convincing evidence that places any British agents at the murder scene".[88] Historian Keith Jeffery states that if British Intelligence agents had been involved in the assassination of Rasputin, "I would have expected to find some trace of that" in the Secret Intelligence Service archives, but no such evidence exists.[89]

Daughter

Rasputin's daughter, Maria Rasputin (born Matryona Rasputina) (1898–1977), emigrated to France after the October Revolution and then to the United States. There, she worked as a dancer and then a lion tamer in a circus.[90]

Notes

- Wilson 1964, pp. 23–26.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 7.

- Smith 2016, p. 14.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 6.

- Smith 2016, pp. 14–15.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 9.

- Smith 2016, pp. 16–17.

- Smith 2016, pp. 17–18.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 14.

- Smith 2016, pp. 20–21.

- Smith 2016, p. 21.

- Smith 2016, p. 22.

- Smith 2016, pp. 23–25.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 17.

- Smith 2016, pp. 23, 26.

- Smith 2016, pp. 25–26.

- Smith 2016, p. 28.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 19–20.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 20.

- Smith 2016, pp. 50–51.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 25.

- Smith 2016, pp. 50–53.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 26.

- Radzinsky 2010, pp. 47–48.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 29.

- Smith 2016, p. 66.

- Smith 2016, p. 57.

- Figes 1998, p. 29.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 30.

- Smith 2016, p. 65.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 29–30, 39.

- Smith 2016, pp. 69–76.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 41.

- Figes 1998, p. 30.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 41–42.

- Ferro 1995, p. 137.

- Shukman 1994, p. 370.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 43.

- Massie 2012, p. 163.

- Massie 2012, p. 168.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 46.

- Massie 2012, p. 192.

- Massie 2012, pp. 193–195.

- Massie 2012, p. 195.

- Massie 2012, pp. 197–198.

- Massie 2012, p. 198.

- Figes 1998, p. 31.

- Ferro 1995, p. 138.

- Figes 1998, pp. 32–33.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 52–53.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 57.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 58–59.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 61.

- Smith, p. 168.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 61–62.

- Radzinsky 2010, p. 434.

- Fuhrmann 1990, pp. 106–107.

- Fuhrmann 1990, p. 108.

- Smith 2016, p. 332.

- Smith 2016, pp. 360–361.

- Smith 2017.

- Fuhrmann 1990, p. 82.

- Fuhrmann 1990, pp. 82–84.

- Radzinsky 2010, p. 256.

- Farquhar 2001, p. 197.

- Moorehead 1958, pp. 107–108.

- Smith 2016, pp. 590, 595.

- Smith 2016, pp. 590–592.

- Smith 2016, p. 590.

- Smith 2016, pp. 590–591.

- Smith 2016, p. 591.

- Smith 2016, pp. 591–592.

- Smith 2016, pp. 597–598.

- Smith 2016, p. 599.

- Smith 2016, p. 600.

- Smith 2016, p. 606.

- Smith 2016, pp. 608–610.

- Smith 2016, p. 610.

- Smith 2016, p. 611.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 217–219.

- Rollins 1982, p. 197.

- Smith 2016, p. 612.

- Smith 2016, p. 650.

- Fuhrmann 2012, p. 226.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 226–227.

- Miller 2004.

- Fuhrmann 2012, pp. 227–229.

- Smith 2016, pp. 631–632.

- Norton-Taylor 2010.

- Adams, Katherine H.; Keene, Michael L. (2012). Women of the American Circus, 1880–1940. McFarland. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-4766-0079-6.

References

- Cook, Andrew (2005). To Kill Rasputin: The Life and Death of Grigori Rasputin. Tempus.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasury of Royal Scandals: The Shocking True Stories of History's Wickedest, Weirdest, Most Wanton Kings, Queens, Tsars, Popes, and Emperors. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-028024-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferro, Marc (1995). Nicholas II: Last of the Tsars. Translated by Pearce, Brian. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509382-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Figes, Orlando (1998). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140243642.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2012). Rasputin: The Untold Story. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-23985-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (1990). Rasputin: A Life. Praeger Frederick A. ISBN 978-0-275-93215-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Massie, Robert K (2012) [1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (Modern Library ed.). ISBN 978-0-679-64561-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Karyn (19 September 2004). "British spy 'fired the shot that finished off Rasputin". The Daily Telegraph.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moorehead, Alan (1958). The Russian Revolution. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0881843316.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norton-Taylor, Richard (21 September 2010). "Graham Greene, Arthur Ransome and Somerset Maugham All Spied for Britain, Admits MI6". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved 26 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2010). The Rasputin File. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-75466-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rollins, Patrick J. (1982). "Rasputin, Grigorii Efimovich". In Wieczynski, Joseph L. (ed.). The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History. 30. Academic International Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shishkin, Oleg (2004). Rasputin : Istorii͡a Prestuplenii͡a. Moscow: Yauza.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shukman, Harold (1994). "Rasputin, Grigori Efimovich". In Shukman, Harold (ed.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution. Blackwell. ISBN 0631195254.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Szasz, Thomas Stephen (1993). A Lexicon of Lunacy: Metaphoric Malady, Moral Responsibility, and Psychiatry. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56000-065-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Douglas (2016). Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-71123-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Douglas (2017). "Grigory Rasputin and the Outbreak of the First World War: June 1914". In Brenton, Tony (ed.). Was Revolution Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0190658939.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Michael (2011). Six: The Real James Bonds 1909–1939. Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84954-264-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Colin (1964). Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Rasputin, Gregory Efimovitch". |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rasputin. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Grigori Rasputin |