Page Corps

The Page Corps (Russian: Пажеский корпус; French: Corps des Pages) was a military academy in Imperial Russia, which prepared sons of the nobility and of senior officers for military service. Similarly, the Imperial School of Jurisprudence prepared boys for civil service. Although not established until 1943, the modern equivalent of the Page Corps and other Imperial military academies can be said to be the Suvorov Military Schools.

History

The Page Corps was founded in 1759 in Saint Petersburg as a school for teaching and training pages and chamber pages. In light of the need for properly trained officers for the Guard units, the Page Corps was reorganized in 1802 into an educational establishment similar to cadet schools. It would accept the sons of the hereditary nobility of Russian lands, and the sons of at least Lieutenant Generals/Vice Admirals or grandsons of full Generals/Admirals.[1] In 1802, the curriculum of the Page Corps was also changed, thereafter based on the ideals of the Order of Saint John.

In 1810, the school was moved to the palace of the Sovereign Order of Saint John of Jerusalem,[2] also known as Vorontsov Palace. It continued at this location in Saint Petersburg for over one hundred years, until the Russian Revolution in 1917.[1]

During the period of reforms of military schools in the 1860s, the Page Corps was turned into a seven-grade establishment, the first five grades being similar to military gymnasiums, and the other two being modelled after military colleges. Beginning in 1885, the Page Corps had seven general classes, where students learned the same sciences offered by cadet schools, and two special classes, where they were taught military science and jurisprudence. By the 1880s, separate infantry, cavalry and artillery departments were in existence.

The Corps des Pages, as it was generally referred to in pre-Revolutionary Russia, was the only military academy (out of about twenty) to prepare future officers for all arms. The others were devoted to specialized training for cavalry, infantry, artillery, engineers, cossacks, topographical studies, etc.[3] While most graduates entered the Russian Imperial Army as officers, a minority opted for diplomatic or civil service careers.

Life in the Page Corps

In common with the other Russian military schools, the Page Corps imposed a harsh regime on its cadets. Corporal punishment involved beatings with a birch for even minor offences, and bullying of younger students by their seniors was common.[4]

Peter Kropotkin's memoirs detail the hazing and other abuse of pages for which the Corps had become notorious.[5] However, the education provided was of a relatively high standard, with courses in mathematics, languages, sciences, and military subjects.

Court role and privileges

The students served on a rotational basis as pages at Court and provided services at ceremonies, including attendance upon individual members of the Imperial family.

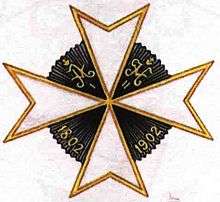

Graduates from the Page Corps had the unique privilege of joining the regiment of their own choice, regardless of the existing vacancies (however, as a matter of etiquette, the consent of the unit's commander was sought beforehand). As serving officers, they wore, on the left side of their tunic, the badge of the Page Corps, modeled after the cross of the Order of Saint John.[1]

Upon graduation, the cadets received the rank of podporuchik (cornet in cavalry). Those who preferred employment as diplomats or government officials, rather than military service, would receive civil service ranks of the 10th, 12th, and 14th class.

Uniform

The Page Corps had a range of uniforms for different purposes. The most spectacular of these was the gala uniform worn for Court functions. This comprised a spiked helmet with white plume, a dark green tunic with gold braid covering the front, white breeches and high boots.

Disbandment

From its inception until 1917, the Page Corps graduated 4,505 officers. An additional 200 were unable to complete their courses because of the revolution of 1917. The school effectively ceased to function following the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in February 1917, and it was finally closed in June of the same year on the orders of Alexander Kerensky, War Minister of the Provisional Government.

References

- Daniel E. A. Perret The Sovereign Order of Saint John of Jerusalem Knights of Malta and the «Corps des Pages», Russia's Dream of Chivalry Archived 2007-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Chebotarev, Tanya and Marvin Lyons (1 December 2002). "The History". The Russian Imperial Corps of Pages, An Online Exhibition Catalog. Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

In the very heart of St. Petersburg stands a magnificently proportioned, medium-sized palace, designed in the mid-eighteenth century by the Italian architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli. The fine old palace was given by the Emperor Paul to the exiled Order of the Hospitalers of Saint John of Jerusalem (the Knights of Malta) in 1796. In 1810, Alexander I gave this palace to the Corps of Pages as the headquarters. It was a gift with great symbolic meaning. The Knights left the Palace with a Catholic chapel in the garden and Maltese Crosses everywhere. The crosses and the chapel remained and the young Pages took very seriously the thought that they were the heirs of the Order, adopting many of its traditions as their own and the white Maltese Cross as their insignia.

- Littauer, Vladimir. Russian Hussar. p. 11. ISBN 1-59048-256-5.

- Robert H.G. Thomas, page 13 "The Russian Army of the Crimean War", ISBN 978-1-85532-161-8

- Kropotkin, Peter (1899). Memoirs of a Revolutionist. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 63.

peter kropotkin memoirs revolutionist.

External links

- Russian Imperial Corps of Pages. An Online Exhibition Catalog // Rare Book & Manuscript Library (RBML) of Columbia University