Fictional universe

A fictional universe, or fictional world, is a self-consistent setting with events, and often other elements, that differ from the real world. It may also be called an imagined, constructed, or fictional realm (or world). Fictional universes may appear in novels, comics, films, television shows, video games, and other creative works.

The subject is most commonly addressed in reference to fictional universes that differ markedly from the real world, such as those that introduce entire fictional cities, countries, or even planets, or those that contradict commonly known facts about the world and its history, or those that feature fantasy or science fiction concepts such as magic or faster than light travel—and especially those in which the deliberate development of the setting is a substantial focus of the work. When a large franchise of related works has two or more somewhat different fictional universes that are each internally consistent but not consistent with each other (such as a distinct plotline and set of characters in a comics version versus a television adaptation), each universe is often referred to as a continuity, though the term continuity as a mass noun usually has a broader meaning in fiction.

Definition

The term was first defined by comics historian Don Markstein, in a 1970 article in CAPA-alpha.[1]

Markstein's criteria

- If characters A and B have met, then they are in the same universe; if characters B and C have met, then, transitively, A and C are in the same universe.

- Characters cannot be connected by real people — otherwise, it could be argued that Superman and the Fantastic Four were in the same universe, as Superman met John F. Kennedy, Kennedy met Neil Armstrong, and Armstrong met the Fantastic Four.

- Characters cannot be connected by characters "that do not originate with the publisher" — otherwise it could be argued that Superman and the Fantastic Four were in the same universe, as both met Hercules.

- Specific fictionalized versions of real people — for instance, the version of Jerry Lewis from DC Comics' The Adventures of Jerry Lewis, who was distinct from the real Jerry Lewis in that he had a housekeeper with magical powers — can be used as connections; this also applies to specific versions of public-domain fictional characters, such as Marvel Comics' version of Hercules or DC Comics' version of Robin Hood.

- Characters are only considered to have met if they appeared together in a story; therefore, characters who simply appeared on the same front cover are not necessarily in the same universe.

Universe vs setting

What distinguishes a fictional universe from a simple setting is the level of detail and internal consistency. A fictional universe has an established continuity and internal logic that must be adhered to throughout the work and even across separate works. So, for instance, many books may be set in conflicting fictional versions of Victorian London, but all the stories of Sherlock Holmes are set in the same Victorian London. However, the various film series based on Sherlock Holmes follow their own separate continuities, thus not taking place in the same fictional universe.

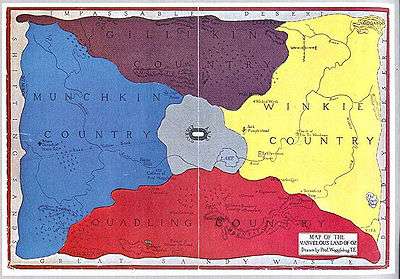

The history and geography of a fictional universe are well defined, and maps and timelines are often included in works set within them. Even new languages may be constructed. When subsequent works are written within the same universe, care is usually taken to ensure that established facts of the canon are not violated. Even if the fictional universe involves concepts such as elements of magic that don't exist in the real world, these must adhere to a set of rules established by the author.

A famous example of a detailed fictional universe is Arda (more popularly known as Middle-earth), of J. R. R. Tolkien's books The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, and The Silmarillion. He created first its languages and then the world itself, which he states was "primarily linguistic in inspiration and was begun in order to provide the necessary 'history' for the Elvish tongues."[2]

A modern example of a fictional universe is that of the Avatar film series, as James Cameron has invented an entire ecosystem, with a team of scientists to test whether it was viable. Additionally, he commissioned a linguistics expert to invent the Na'vi language.

Virtually every successful fictional TV series or comic book develops its own "universe" to keep track of the various episodes or issues. Writers for that series must follow its story bible,[3] which often becomes the series canon.

Frequently, when a series is perceived by its creators as too complicated or too self-inconsistent (because of, for example, too many writers), the producers or publishers may introduce retroactive continuity (retcon) to make future editions easier to write and more consistent. This creates an alternate universe that future authors can write about. These stories about the universe or universes that existed before the retcon are usually not canonical, unless the franchise-holder gives permission. Crisis on Infinite Earths was an especially sweeping example.

Some writers choose to introduce elements or characters from one work into another, to present the idea that both works are set in the same universe. For example, the character of Ursula Buffay from American sitcom Mad About You was also a recurring guest star in Friends, despite the two series having little else in common. Fellow NBC series Seinfeld also contained crossover references to Mad About You. L. Frank Baum introduced the characters of Cap'n Bill and Trot (from The Sea Fairies) into the Oz series in The Scarecrow of Oz, and they made a number of appearances in later Oz books. In science fiction, A. Bertram Chandler introduced into his future Galactic civilization the character Dominic Flandry from Poul Anderson's quite different Galactic future (he had Anderson's consent) – on the assumption that these were two alternate history timelines and that people could on some occasions cross from one to the other.

Scope

Sir Thomas More's Utopia is one of the earliest examples of a cohesive fictional world with its own rules and functional concepts, but it comprises only one small island. Later fictional universes, like Robert E. Howard's Conan the Cimmerian stories or Lev Grossman's Fillory, are global in scope and some, like Star Wars, Honorverse, BattleTech, or the Lensman series, are galactic or even intergalactic.

A fictional universe may even concern itself with more than one interconnected universe through fictional devices such as dreams, "time travel" or "parallel worlds". Such a series of interconnected universes is often called a multiverse. Such multiverses have been featured prominently in science fiction since at least the mid-20th century.

The classic Star Trek episode "Mirror, Mirror" introduced the Mirror Universe, in which the crew members of the Starship Enterprise were brutal rather than compassionate. The 2009 movie Star Trek created an "alternate reality" and freed the Star Trek franchise from continuity issues. In the mid-1980s, DC Comics Crisis on Infinite Earths streamlined its fictional continuity by destroying most of its alternate universes.

Format

A fictional universe can be contained in a single work, as in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four or Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, or in serialized, series-based, open-ended or round robin-style fiction.

In most small-scale fictional universes, general properties and timeline events fit into a consistently organized continuity. However, in the case of universes that are rewritten or revised by different writers, editors, or producers, this continuity may be violated, by accident or by design.

The occasional publishing use of retroactive continuity (retcon) often occurs due to this kind of revision or oversight. Members of fandom often create a kind of fan-made canon (fanon) to patch up such errors; "fanon" that becomes generally accepted sometimes becomes actual canon. Other fan-made additions to a universe (fan fiction, alternate universe, pastiche, parody) are usually not considered canonical unless they get authorized.

Collaboration

Shared universes often come about when a fictional universe achieves great commercial success and attracts other media. For example, a successful movie may catch the attention of various book authors, who wish to write stories based on that movie. Under U.S. law, the copyright-holder retains control of all other derivative works, including those written by other authors, but they might not feel comfortable in those other mediums or may feel that other individuals will do a better job; therefore, they may open up the copyright on a shared-universe basis. The degree to which the copyright-holder or franchise retains control is often one of the points in the license agreement.

For example, the comic book Superman was so popular that it spawned over 30 different radio, television, and movie series and a similar number of video games, as well as theme park rides, books, and songs. In the other direction, both Star Trek and Star Wars are responsible for hundreds of books and games of varying levels of canonicity.

Fictional universes are sometimes shared by multiple prose authors, with each author's works in that universe being granted approximately equal canonical status. For example, Larry Niven's fictional universe Known Space has an approximately 135-year period in which Niven allows other authors to write stories about the Man-Kzin Wars. Other fictional universes, like the Ring of Fire series, actively court canonical stimulus from fans, but gate and control the changes through a formalized process and the final say of the editor and universe creator.[4]

Other universes are created by one or several authors but are intended to be used non-canonically by others, such as the fictional settings for games, particularly role-playing games and video games. Settings for the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons are called campaign settings; other games have also incorporated this term on occasion. Virtual worlds are fictional worlds in which online computer games, notably MMORPGs and MUDs, take place. A fictional crossover occurs when two or more fictional characters, series or universes cross over with one another, usually in the context of a character created by one author or owned by one company meeting a character created or owned by another. In the case where two fictional universes covering entire actual universes cross over, physical travel from one universe to another may actually occur in the course of the story. Such crossovers are usually, but not always, considered non-canonical by their creators or by those in charge of the properties involved.

Lists of fictional universes

For lists of fictional universes see:

- List of fictional shared universes in film and television

- List of fictional universes in animation and comics

- List of fictional universes in literature

- List of science fiction universes

See also

- Alternate history

- Alternate universe (fan fiction)

- Constructed world

- Continuity (fiction)

- Diegesis

- Expanded universe

- Shared universe

- Fantasy world

- Fictional country

- Fictional location

- Future history

- Index of fictional places

- List of fantasy worlds

- Mythical place

- Paracosm

- Parallel universe

- Planets in science fiction

- Setting (fiction)

- Simulated reality

- Virtual reality

- Multiverse

References

- "THE MERCHANT OF VENICE meets THE SHIEK OF ARABI", by Don Markstein (as "Om Markstein Sklom Stu"), in CAPA-alpha #71 (September 1970); archived at Toonopedia

- Tolkien, J. R. R. "Foreword". The Fellowship of the Ring.

- Espenson, Jane (April 2008). "How to Give Maris Hives, Alphabetized". JaneEspenson.com. This is a blog entry on the subject by a professional scriptwriter.

- Flint, Eric and various others. Grantville Gazette III. Thomas Kidd (cover art). Baen Books. pp. 311–313. ISBN 978-1-4165-0941-7. ISBN 1-4165-0941-0.

The print published and e-published Grantville Gazettes all contain a post book afterword detailing where and how to submit a manuscript to the fictional canon oversight process for the 1632 series.

- Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi: The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, New York : Harcourt Brace, c2000. ISBN 0-15-100541-9

- Brian Stableford: The Dictionary of Science Fiction Places, New York : Wonderland Press, c1999. ISBN 0-684-84958-5

- Diana Wynne Jones: The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, New York : Firebird, 2006. ISBN 0-14-240722-4, Explains and parodies the common features of a standard fantasy world

- George Ochoa and Jeffery Osier: Writer's Guide to Creating A Science Fiction Universe, Cincinnati, Ohio : Writer's Digest Books, 1993. ISBN 0-89879-536-2

- Michael Page and Robert Ingpen : Encyclopedia of Things That Never Were: Creatures, Places, and People, 1987. ISBN 0-14-010008-3