Eye

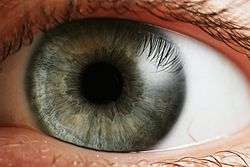

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide animals with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and convert it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons. In higher organisms, the eye is a complex optical system which collects light from the surrounding environment, regulates its intensity through a diaphragm, focuses it through an adjustable assembly of lenses to form an image, converts this image into a set of electrical signals, and transmits these signals to the brain through complex neural pathways that connect the eye via the optic nerve to the visual cortex and other areas of the brain. Eyes with resolving power have come in ten fundamentally different forms, and 96% of animal species possess a complex optical system.[1] Image-resolving eyes are present in molluscs, chordates and arthropods.[2]

| Eye | |

|---|---|

| |

Compound eye of Antarctic krill | |

| Details | |

| System | Nervous |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | oculus |

| MeSH | D005123 |

| TA | A15.2.00.001 A01.1.00.007 |

| FMA | 54448 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The most simple eyes, pit eyes, are eye-spots which may be set into a pit to reduce the angles of light that enters and affects the eye-spot, to allow the organism to deduce the angle of incoming light.[1] From more complex eyes, retinal photosensitive ganglion cells send signals along the retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic nuclei to effect circadian adjustment and to the pretectal area to control the pupillary light reflex.

Overview

Complex eyes can distinguish shapes and colours. The visual fields of many organisms, especially predators, involve large areas of binocular vision to improve depth perception. In other organisms, eyes are located so as to maximise the field of view, such as in rabbits and horses, which have monocular vision.

The first proto-eyes evolved among animals 600 million years ago about the time of the Cambrian explosion.[3] The last common ancestor of animals possessed the biochemical toolkit necessary for vision, and more advanced eyes have evolved in 96% of animal species in six of the ~35[lower-alpha 1] main phyla.[1] In most vertebrates and some molluscs, the eye works by allowing light to enter and project onto a light-sensitive panel of cells, known as the retina, at the rear of the eye. The cone cells (for colour) and the rod cells (for low-light contrasts) in the retina detect and convert light into neural signals for vision. The visual signals are then transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve. Such eyes are typically roughly spherical, filled with a transparent gel-like substance called the vitreous humour, with a focusing lens and often an iris; the relaxing or tightening of the muscles around the iris change the size of the pupil, thereby regulating the amount of light that enters the eye,[4] and reducing aberrations when there is enough light.[5] The eyes of most cephalopods, fish, amphibians and snakes have fixed lens shapes, and focusing vision is achieved by telescoping the lens—similar to how a camera focuses.[6]

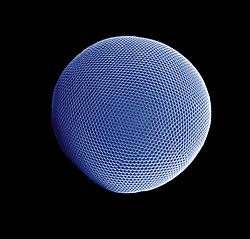

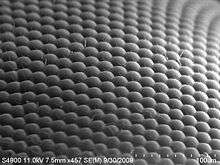

Compound eyes are found among the arthropods and are composed of many simple facets which, depending on the details of anatomy, may give either a single pixelated image or multiple images, per eye. Each sensor has its own lens and photosensitive cell(s). Some eyes have up to 28,000 such sensors, which are arranged hexagonally, and which can give a full 360° field of vision. Compound eyes are very sensitive to motion. Some arthropods, including many Strepsiptera, have compound eyes of only a few facets, each with a retina capable of creating an image, creating vision. With each eye viewing a different thing, a fused image from all the eyes is produced in the brain, providing very different, high-resolution images.

Possessing detailed hyperspectral colour vision, the Mantis shrimp has been reported to have the world's most complex colour vision system.[7] Trilobites, which are now extinct, had unique compound eyes. They used clear calcite crystals to form the lenses of their eyes. In this, they differ from most other arthropods, which have soft eyes. The number of lenses in such an eye varied; however, some trilobites had only one, and some had thousands of lenses in one eye.

In contrast to compound eyes, simple eyes are those that have a single lens. For example, jumping spiders have a large pair of simple eyes with a narrow field of view, supported by an array of other, smaller eyes for peripheral vision. Some insect larvae, like caterpillars, have a different type of simple eye (stemmata) which usually provides only a rough image, but (as in sawfly larvae) can possess resolving powers of 4 degrees of arc, be polarization-sensitive and capable of increasing its absolute sensitivity at night by a factor of 1,000 or more.[8] Some of the simplest eyes, called ocelli, can be found in animals like some of the snails, which cannot actually "see" in the normal sense. They do have photosensitive cells, but no lens and no other means of projecting an image onto these cells. They can distinguish between light and dark, but no more. This enables snails to keep out of direct sunlight. In organisms dwelling near deep-sea vents, compound eyes have been secondarily simplified and adapted to spot the infra-red light produced by the hot vents—in this way the bearers can spot hot springs and avoid being boiled alive.[9]

Types

There are ten different eye layouts—indeed every technological method of capturing an optical image commonly used by human beings, with the exceptions of zoom and Fresnel lenses, occur in nature.[1] Eye types can be categorised into "simple eyes", with one concave photoreceptive surface, and "compound eyes", which comprise a number of individual lenses laid out on a convex surface.[1] Note that "simple" does not imply a reduced level of complexity or acuity. Indeed, any eye type can be adapted for almost any behaviour or environment. The only limitations specific to eye types are that of resolution—the physics of compound eyes prevents them from achieving a resolution better than 1°. Also, superposition eyes can achieve greater sensitivity than apposition eyes, so are better suited to dark-dwelling creatures.[1] Eyes also fall into two groups on the basis of their photoreceptor's cellular construction, with the photoreceptor cells either being cilliated (as in the vertebrates) or rhabdomeric. These two groups are not monophyletic; the cnidaria also possess cilliated cells, [10] and some gastropods,[11] as well as some annelids possess both.[12]

Some organisms have photosensitive cells that do nothing but detect whether the surroundings are light or dark, which is sufficient for the entrainment of circadian rhythms. These are not considered eyes because they lack enough structure to be considered an organ, and do not produce an image.[13]

Non-compound eyes

Simple eyes are rather ubiquitous, and lens-bearing eyes have evolved at least seven times in vertebrates, cephalopods, annelids, crustaceans and cubozoa.[14]

Pit eyes

Pit eyes, also known as stemma, are eye-spots which may be set into a pit to reduce the angles of light that enters and affects the eye-spot, to allow the organism to deduce the angle of incoming light.[1] Found in about 85% of phyla, these basic forms were probably the precursors to more advanced types of "simple eyes". They are small, comprising up to about 100 cells covering about 100 µm.[1] The directionality can be improved by reducing the size of the aperture, by incorporating a reflective layer behind the receptor cells, or by filling the pit with a refractile material.[1]

Pit vipers have developed pits that function as eyes by sensing thermal infra-red radiation, in addition to their optical wavelength eyes like those of other vertebrates (see infrared sensing in snakes). However, pit organs are fitted with receptors rather different to photoreceptors, namely a specific transient receptor potential channel (TRP channels) called TRPV1. The main difference is that photoreceptors are G-protein coupled receptors but TRP are ion channels.

Spherical lens eye

The resolution of pit eyes can be greatly improved by incorporating a material with a higher refractive index to form a lens, which may greatly reduce the blur radius encountered—hence increasing the resolution obtainable.[1] The most basic form, seen in some gastropods and annelids, consists of a lens of one refractive index. A far sharper image can be obtained using materials with a high refractive index, decreasing to the edges; this decreases the focal length and thus allows a sharp image to form on the retina.[1] This also allows a larger aperture for a given sharpness of image, allowing more light to enter the lens; and a flatter lens, reducing spherical aberration.[1] Such a non-homogeneous lens is necessary for the focal length to drop from about 4 times the lens radius, to 2.5 radii.[1]

Heterogeneous eyes have evolved at least nine times: four or more times in gastropods, once in the copepods, once in the annelids, once in the cephalopods,[1] and once in the chitons, which have aragonite lenses.[15] No extant aquatic organisms possess homogeneous lenses; presumably the evolutionary pressure for a heterogeneous lens is great enough for this stage to be quickly "outgrown".[1]

This eye creates an image that is sharp enough that motion of the eye can cause significant blurring. To minimise the effect of eye motion while the animal moves, most such eyes have stabilising eye muscles.[1]

The ocelli of insects bear a simple lens, but their focal point always lies behind the retina; consequently, they can never form a sharp image. Ocelli (pit-type eyes of arthropods) blur the image across the whole retina, and are consequently excellent at responding to rapid changes in light intensity across the whole visual field; this fast response is further accelerated by the large nerve bundles which rush the information to the brain.[16] Focusing the image would also cause the sun's image to be focused on a few receptors, with the possibility of damage under the intense light; shielding the receptors would block out some light and thus reduce their sensitivity.[16] This fast response has led to suggestions that the ocelli of insects are used mainly in flight, because they can be used to detect sudden changes in which way is up (because light, especially UV light which is absorbed by vegetation, usually comes from above).[16]

Multiple lenses

Some marine organisms bear more than one lens; for instance the copepod Pontella has three. The outer has a parabolic surface, countering the effects of spherical aberration while allowing a sharp image to be formed. Another copepod, Copilia, has two lenses in each eye, arranged like those in a telescope.[1] Such arrangements are rare and poorly understood, but represent an alternative construction.

Multiple lenses are seen in some hunters such as eagles and jumping spiders, which have a refractive cornea: these have a negative lens, enlarging the observed image by up to 50% over the receptor cells, thus increasing their optical resolution.[1]

Refractive cornea

In the eyes of most mammals, birds, reptiles, and most other terrestrial vertebrates (along with spiders and some insect larvae) the vitreous fluid has a higher refractive index than the air.[1] In general, the lens is not spherical. Spherical lenses produce spherical aberration. In refractive corneas, the lens tissue is corrected with inhomogeneous lens material (see Luneburg lens), or with an aspheric shape.[1] Flattening the lens has a disadvantage; the quality of vision is diminished away from the main line of focus. Thus, animals that have evolved with a wide field-of-view often have eyes that make use of an inhomogeneous lens.[1]

As mentioned above, a refractive cornea is only useful out of water. In water, there is little difference in refractive index between the vitreous fluid and the surrounding water. Hence creatures that have returned to the water—penguins and seals, for example—lose their highly curved cornea and return to lens-based vision. An alternative solution, borne by some divers, is to have a very strongly focusing cornea.[1]

Reflector eyes

An alternative to a lens is to line the inside of the eye with "mirrors", and reflect the image to focus at a central point.[1] The nature of these eyes means that if one were to peer into the pupil of an eye, one would see the same image that the organism would see, reflected back out.[1]

Many small organisms such as rotifers, copepods and flatworms use such organs, but these are too small to produce usable images.[1] Some larger organisms, such as scallops, also use reflector eyes. The scallop Pecten has up to 100 millimetre-scale reflector eyes fringing the edge of its shell. It detects moving objects as they pass successive lenses.[1]

There is at least one vertebrate, the spookfish, whose eyes include reflective optics for focusing of light. Each of the two eyes of a spookfish collects light from both above and below; the light coming from above is focused by a lens, while that coming from below, by a curved mirror composed of many layers of small reflective plates made of guanine crystals.[17]

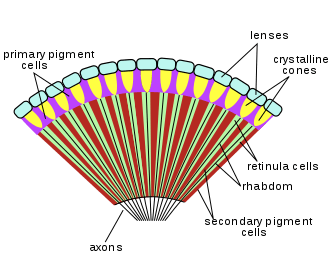

Compound eyes

A compound eye may consist of thousands of individual photoreceptor units or ommatidia (ommatidium, singular). The image perceived is a combination of inputs from the numerous ommatidia (individual "eye units"), which are located on a convex surface, thus pointing in slightly different directions. Compared with simple eyes, compound eyes possess a very large view angle, and can detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarisation of light.[18] Because the individual lenses are so small, the effects of diffraction impose a limit on the possible resolution that can be obtained (assuming that they do not function as phased arrays). This can only be countered by increasing lens size and number. To see with a resolution comparable to our simple eyes, humans would require very large compound eyes, around 11 metres (36 ft) in radius.[19]

Compound eyes fall into two groups: apposition eyes, which form multiple inverted images, and superposition eyes, which form a single erect image.[20] Compound eyes are common in arthropods, annelids and some bivalved molluscs.[21] Compound eyes in arthropods grow at their margins by the addition of new ommatidia.[22]

Apposition eyes

Apposition eyes are the most common form of eyes and are presumably the ancestral form of compound eyes. They are found in all arthropod groups, although they may have evolved more than once within this phylum.[1] Some annelids and bivalves also have apposition eyes. They are also possessed by Limulus, the horseshoe crab, and there are suggestions that other chelicerates developed their simple eyes by reduction from a compound starting point.[1] (Some caterpillars appear to have evolved compound eyes from simple eyes in the opposite fashion.)

Apposition eyes work by gathering a number of images, one from each eye, and combining them in the brain, with each eye typically contributing a single point of information. The typical apposition eye has a lens focusing light from one direction on the rhabdom, while light from other directions is absorbed by the dark wall of the ommatidium.

Superposition eyes

The second type is named the superposition eye. The superposition eye is divided into three types:

- refracting,

- reflecting and

- parabolic superposition

The refracting superposition eye has a gap between the lens and the rhabdom, and no side wall. Each lens takes light at an angle to its axis and reflects it to the same angle on the other side. The result is an image at half the radius of the eye, which is where the tips of the rhabdoms are. This type of compound eye, for which a minimal size exists below which effective superposition cannot occur,[23] is normally found in nocturnal insects, because it can create images up to 1000 times brighter than equivalent apposition eyes, though at the cost of reduced resolution.[24] In the parabolic superposition compound eye type, seen in arthropods such as mayflies, the parabolic surfaces of the inside of each facet focus light from a reflector to a sensor array. Long-bodied decapod crustaceans such as shrimp, prawns, crayfish and lobsters are alone in having reflecting superposition eyes, which also have a transparent gap but use corner mirrors instead of lenses.

Parabolic superposition

This eye type functions by refracting light, then using a parabolic mirror to focus the image; it combines features of superposition and apposition eyes.[9]

Other

Another kind of compound eye, found in males of Order Strepsiptera, employs a series of simple eyes—eyes having one opening that provides light for an entire image-forming retina. Several of these eyelets together form the strepsipteran compound eye, which is similar to the 'schizochroal' compound eyes of some trilobites.[25] Because each eyelet is a simple eye, it produces an inverted image; those images are combined in the brain to form one unified image. Because the aperture of an eyelet is larger than the facets of a compound eye, this arrangement allows vision under low light levels.[1]

Good fliers such as flies or honey bees, or prey-catching insects such as praying mantis or dragonflies, have specialised zones of ommatidia organised into a fovea area which gives acute vision. In the acute zone, the eyes are flattened and the facets larger. The flattening allows more ommatidia to receive light from a spot and therefore higher resolution. The black spot that can be seen on the compound eyes of such insects, which always seems to look directly at the observer, is called a pseudopupil. This occurs because the ommatidia which one observes "head-on" (along their optical axes) absorb the incident light, while those to one side reflect it.[26]

There are some exceptions from the types mentioned above. Some insects have a so-called single lens compound eye, a transitional type which is something between a superposition type of the multi-lens compound eye and the single lens eye found in animals with simple eyes. Then there is the mysid shrimp, Dioptromysis paucispinosa. The shrimp has an eye of the refracting superposition type, in the rear behind this in each eye there is a single large facet that is three times in diameter the others in the eye and behind this is an enlarged crystalline cone. This projects an upright image on a specialised retina. The resulting eye is a mixture of a simple eye within a compound eye.

Another version is a compound eye often referred to as "pseudofaceted", as seen in Scutigera.[27] This type of eye consists of a cluster of numerous ommatidia on each side of the head, organised in a way that resembles a true compound eye.

The body of Ophiocoma wendtii, a type of brittle star, is covered with ommatidia, turning its whole skin into a compound eye. The same is true of many chitons. The tube feet of sea urchins contain photoreceptor proteins, which together act as a compound eye; they lack screening pigments, but can detect the directionality of light by the shadow cast by its opaque body.[28]

Nutrients

The ciliary body is triangular in horizontal section and is coated by a double layer, the ciliary epithelium. The inner layer is transparent and covers the vitreous body, and is continuous from the neural tissue of the retina. The outer layer is highly pigmented, continuous with the retinal pigment epithelium, and constitutes the cells of the dilator muscle.

The vitreous is the transparent, colourless, gelatinous mass that fills the space between the lens of the eye and the retina lining the back of the eye.[29] It is produced by certain retinal cells. It is of rather similar composition to the cornea, but contains very few cells (mostly phagocytes which remove unwanted cellular debris in the visual field, as well as the hyalocytes of Balazs of the surface of the vitreous, which reprocess the hyaluronic acid), no blood vessels, and 98–99% of its volume is water (as opposed to 75% in the cornea) with salts, sugars, vitrosin (a type of collagen), a network of collagen type II fibres with the mucopolysaccharide hyaluronic acid, and also a wide array of proteins in micro amounts. Amazingly, with so little solid matter, it tautly holds the eye.

Evolution

Photoreception is phylogenetically very old, with various theories of phylogenesis.[30] The common origin (monophyly) of all animal eyes is now widely accepted as fact. This is based upon the shared genetic features of all eyes; that is, all modern eyes, varied as they are, have their origins in a proto-eye believed to have evolved some 540 million years ago,[31][32][33] and the PAX6 gene is considered a key factor in this. The majority of the advancements in early eyes are believed to have taken only a few million years to develop, since the first predator to gain true imaging would have touched off an "arms race"[34] among all species that did not flee the photopic environment. Prey animals and competing predators alike would be at a distinct disadvantage without such capabilities and would be less likely to survive and reproduce. Hence multiple eye types and subtypes developed in parallel (except those of groups, such as the vertebrates, that were only forced into the photopic environment at a late stage).

Eyes in various animals show adaptation to their requirements. For example, the eye of a bird of prey has much greater visual acuity than a human eye, and in some cases can detect ultraviolet radiation. The different forms of eye in, for example, vertebrates and molluscs are examples of parallel evolution, despite their distant common ancestry. Phenotypic convergence of the geometry of cephalopod and most vertebrate eyes creates the impression that the vertebrate eye evolved from an imaging cephalopod eye, but this is not the case, as the reversed roles of their respective ciliary and rhabdomeric opsin classes[35] and different lens crystallins show.[36]

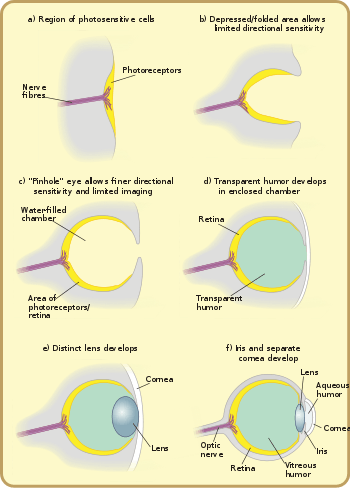

The very earliest "eyes", called eye-spots, were simple patches of photoreceptor protein in unicellular animals. In multicellular beings, multicellular eyespots evolved, physically similar to the receptor patches for taste and smell. These eyespots could only sense ambient brightness: they could distinguish light and dark, but not the direction of the light source.[1]

Through gradual change, the eye-spots of species living in well-lit environments depressed into a shallow "cup" shape. The ability to slightly discriminate directional brightness was achieved by using the angle at which the light hit certain cells to identify the source. The pit deepened over time, the opening diminished in size, and the number of photoreceptor cells increased, forming an effective pinhole camera that was capable of dimly distinguishing shapes.[37] However, the ancestors of modern hagfish, thought to be the protovertebrate,[35] were evidently pushed to very deep, dark waters, where they were less vulnerable to sighted predators, and where it is advantageous to have a convex eye-spot, which gathers more light than a flat or concave one. This would have led to a somewhat different evolutionary trajectory for the vertebrate eye than for other animal eyes.

The thin overgrowth of transparent cells over the eye's aperture, originally formed to prevent damage to the eyespot, allowed the segregated contents of the eye chamber to specialise into a transparent humour that optimised colour filtering, blocked harmful radiation, improved the eye's refractive index, and allowed functionality outside of water. The transparent protective cells eventually split into two layers, with circulatory fluid in between that allowed wider viewing angles and greater imaging resolution, and the thickness of the transparent layer gradually increased, in most species with the transparent crystallin protein.[38]

The gap between tissue layers naturally formed a biconvex shape, an optimally ideal structure for a normal refractive index. Independently, a transparent layer and a nontransparent layer split forward from the lens: the cornea and iris. Separation of the forward layer again formed a humour, the aqueous humour. This increased refractive power and again eased circulatory problems. Formation of a nontransparent ring allowed more blood vessels, more circulation, and larger eye sizes.[38]

Relationship to life requirements

Eyes are generally adapted to the environment and life requirements of the organism which bears them. For instance, the distribution of photoreceptors tends to match the area in which the highest acuity is required, with horizon-scanning organisms, such as those that live on the African plains, having a horizontal line of high-density ganglia, while tree-dwelling creatures which require good all-round vision tend to have a symmetrical distribution of ganglia, with acuity decreasing outwards from the centre.

Of course, for most eye types, it is impossible to diverge from a spherical form, so only the density of optical receptors can be altered. In organisms with compound eyes, it is the number of ommatidia rather than ganglia that reflects the region of highest data acquisition.[1]:23–24 Optical superposition eyes are constrained to a spherical shape, but other forms of compound eyes may deform to a shape where more ommatidia are aligned to, say, the horizon, without altering the size or density of individual ommatidia.[39] Eyes of horizon-scanning organisms have stalks so they can be easily aligned to the horizon when this is inclined, for example, if the animal is on a slope.[26]

An extension of this concept is that the eyes of predators typically have a zone of very acute vision at their centre, to assist in the identification of prey.[39] In deep water organisms, it may not be the centre of the eye that is enlarged. The hyperiid amphipods are deep water animals that feed on organisms above them. Their eyes are almost divided into two, with the upper region thought to be involved in detecting the silhouettes of potential prey—or predators—against the faint light of the sky above. Accordingly, deeper water hyperiids, where the light against which the silhouettes must be compared is dimmer, have larger "upper-eyes", and may lose the lower portion of their eyes altogether.[39] In the giant Antarctic isopod Glyptonotus a small ventral compound eye is physically completely separated from the much larger dorsal compound eye.[40] Depth perception can be enhanced by having eyes which are enlarged in one direction; distorting the eye slightly allows the distance to the object to be estimated with a high degree of accuracy.[9]

Acuity is higher among male organisms that mate in mid-air, as they need to be able to spot and assess potential mates against a very large backdrop.[39] On the other hand, the eyes of organisms which operate in low light levels, such as around dawn and dusk or in deep water, tend to be larger to increase the amount of light that can be captured.[39]

It is not only the shape of the eye that may be affected by lifestyle. Eyes can be the most visible parts of organisms, and this can act as a pressure on organisms to have more transparent eyes at the cost of function.[39]

Eyes may be mounted on stalks to provide better all-round vision, by lifting them above an organism's carapace; this also allows them to track predators or prey without moving the head.[9]

Physiology

Visual acuity

Visual acuity, or resolving power, is "the ability to distinguish fine detail" and is the property of cone cells.[41] It is often measured in cycles per degree (CPD), which measures an angular resolution, or how much an eye can differentiate one object from another in terms of visual angles. Resolution in CPD can be measured by bar charts of different numbers of white/black stripe cycles. For example, if each pattern is 1.75 cm wide and is placed at 1 m distance from the eye, it will subtend an angle of 1 degree, so the number of white/black bar pairs on the pattern will be a measure of the cycles per degree of that pattern. The highest such number that the eye can resolve as stripes, or distinguish from a grey block, is then the measurement of visual acuity of the eye.

For a human eye with excellent acuity, the maximum theoretical resolution is 50 CPD[42] (1.2 arcminute per line pair, or a 0.35 mm line pair, at 1 m). A rat can resolve only about 1 to 2 CPD.[43] A horse has higher acuity through most of the visual field of its eyes than a human has, but does not match the high acuity of the human eye's central fovea region.[44]

Spherical aberration limits the resolution of a 7 mm pupil to about 3 arcminutes per line pair. At a pupil diameter of 3 mm, the spherical aberration is greatly reduced, resulting in an improved resolution of approximately 1.7 arcminutes per line pair.[45] A resolution of 2 arcminutes per line pair, equivalent to a 1 arcminute gap in an optotype, corresponds to 20/20 (normal vision) in humans.

However, in the compound eye, the resolution is related to the size of individual ommatidia and the distance between neighbouring ommatidia. Physically these cannot be reduced in size to achieve the acuity seen with single lensed eyes as in mammals. Compound eyes have a much lower acuity than vertebrate eyes.[46]

Colour perception

"Colour vision is the faculty of the organism to distinguish lights of different spectral qualities."[47] All organisms are restricted to a small range of electromagnetic spectrum; this varies from creature to creature, but is mainly between wavelengths of 400 and 700 nm.[48] This is a rather small section of the electromagnetic spectrum, probably reflecting the submarine evolution of the organ: water blocks out all but two small windows of the EM spectrum, and there has been no evolutionary pressure among land animals to broaden this range.[49]

The most sensitive pigment, rhodopsin, has a peak response at 500 nm.[50] Small changes to the genes coding for this protein can tweak the peak response by a few nm;[2] pigments in the lens can also filter incoming light, changing the peak response.[2] Many organisms are unable to discriminate between colours, seeing instead in shades of grey; colour vision necessitates a range of pigment cells which are primarily sensitive to smaller ranges of the spectrum. In primates, geckos, and other organisms, these take the form of cone cells, from which the more sensitive rod cells evolved.[50] Even if organisms are physically capable of discriminating different colours, this does not necessarily mean that they can perceive the different colours; only with behavioural tests can this be deduced.[2]

Most organisms with colour vision can detect ultraviolet light. This high energy light can be damaging to receptor cells. With a few exceptions (snakes, placental mammals), most organisms avoid these effects by having absorbent oil droplets around their cone cells. The alternative, developed by organisms that had lost these oil droplets in the course of evolution, is to make the lens impervious to UV light—this precludes the possibility of any UV light being detected, as it does not even reach the retina.[50]

Rods and cones

The retina contains two major types of light-sensitive photoreceptor cells used for vision: the rods and the cones.

Rods cannot distinguish colours, but are responsible for low-light (scotopic) monochrome (black-and-white) vision; they work well in dim light as they contain a pigment, rhodopsin (visual purple), which is sensitive at low light intensity, but saturates at higher (photopic) intensities. Rods are distributed throughout the retina but there are none at the fovea and none at the blind spot. Rod density is greater in the peripheral retina than in the central retina.

Cones are responsible for colour vision. They require brighter light to function than rods require. In humans, there are three types of cones, maximally sensitive to long-wavelength, medium-wavelength, and short-wavelength light (often referred to as red, green, and blue, respectively, though the sensitivity peaks are not actually at these colours). The colour seen is the combined effect of stimuli to, and responses from, these three types of cone cells. Cones are mostly concentrated in and near the fovea. Only a few are present at the sides of the retina. Objects are seen most sharply in focus when their images fall on the fovea, as when one looks at an object directly. Cone cells and rods are connected through intermediate cells in the retina to nerve fibres of the optic nerve. When rods and cones are stimulated by light, they connect through adjoining cells within the retina to send an electrical signal to the optic nerve fibres. The optic nerves send off impulses through these fibres to the brain.[50]

Pigmentation

The pigment molecules used in the eye are various, but can be used to define the evolutionary distance between different groups, and can also be an aid in determining which are closely related—although problems of convergence do exist.[50]

Opsins are the pigments involved in photoreception. Other pigments, such as melanin, are used to shield the photoreceptor cells from light leaking in from the sides. The opsin protein group evolved long before the last common ancestor of animals, and has continued to diversify since.[2]

There are two types of opsin involved in vision; c-opsins, which are associated with ciliary-type photoreceptor cells, and r-opsins, associated with rhabdomeric photoreceptor cells.[51] The eyes of vertebrates usually contain ciliary cells with c-opsins, and (bilaterian) invertebrates have rhabdomeric cells in the eye with r-opsins. However, some ganglion cells of vertebrates express r-opsins, suggesting that their ancestors used this pigment in vision, and that remnants survive in the eyes.[51] Likewise, c-opsins have been found to be expressed in the brain of some invertebrates. They may have been expressed in ciliary cells of larval eyes, which were subsequently resorbed into the brain on metamorphosis to the adult form.[51] C-opsins are also found in some derived bilaterian-invertebrate eyes, such as the pallial eyes of the bivalve molluscs; however, the lateral eyes (which were presumably the ancestral type for this group, if eyes evolved once there) always use r-opsins.[51] Cnidaria, which are an outgroup to the taxa mentioned above, express c-opsins—but r-opsins are yet to be found in this group.[51] Incidentally, the melanin produced in the cnidaria is produced in the same fashion as that in vertebrates, suggesting the common descent of this pigment.[51]

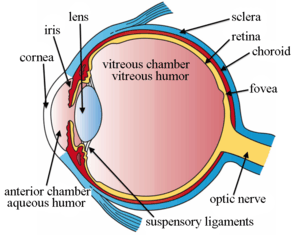

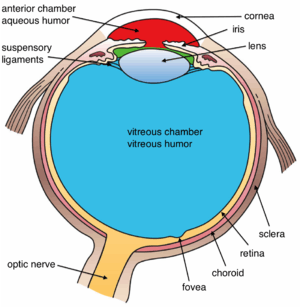

Additional images

The structures of the eye labelled

The structures of the eye labelled Another view of the eye and the structures of the eye labelled

Another view of the eye and the structures of the eye labelled

See also

Notes

- There is no universal consensus on the precise total number of phyla Animalia; the stated figure varies slightly from author to author.

References

Citations

- Land, M.F.; Fernald, R.D. (1992). "The evolution of eyes". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 15: 1–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000245. PMID 1575438.

- Frentiu, Francesca D.; Adriana D. Briscoe (2008). "A butterfly eye's view of birds". BioEssays. 30 (11–12): 1151–1162. doi:10.1002/bies.20828. PMID 18937365.

- Breitmeyer, Bruno (2010). Blindspots: The Many Ways We Cannot See. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-539426-9.

- Nairne, James (2005). Psychology. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-495-03150-5. OCLC 61361417.

- Bruce, Vicki; Green, Patrick R.; Georgeson, Mark A. (1996). Visual Perception: Physiology, Psychology and Ecology. Psychology Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-86377-450-8.

- BioMedia Associates Educational Biology Site: What animal has a more sophisticated eye, Octopus or Insect? Archived 2008-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "Who You Callin' "Shrimp"?". National Wildlife Magazine. Nwf.org. 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- Meyer-Rochow, V.B. (1974). "Structure and function of the larval eye of the sawfly larva Perga". Journal of Insect Physiology. 20 (8): 1565–1591. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(74)90087-0. PMID 4854430.

- Cronin, T.W.; Porter, M.L. (2008). "Exceptional Variation on a Common Theme: the Evolution of Crustacean Compound Eyes". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 1 (4): 463–475. doi:10.1007/s12052-008-0085-0.

- Kozmik, Z.; Ruzickova, J.; Jonasova, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Vopalensky, P.; Kozmikova, I.; Strnad, H.; Kawamura, S.; Piatigorsky, J.; et al. (2008). "Assembly of the cnidarian camera-type eye from vertebrate-like components" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (26): 8989–8993. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8989K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800388105. PMC 2449352. PMID 18577593.

- Zhukov, ZH; Borisseko, SL; Zieger, MV; Vakoliuk, IA; Meyer-Rochow, VB (2006). "The eye of the freshwater prosobranch gastropod Viviparus viviparus: ultrastructure, electrophysiology and behaviour". Acta Zoologica. 87: 13–24. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2006.00216.x.

- Fernald, Russell D. (2006). "Casting a Genetic Light on the Evolution of Eyes" (PDF). Science. 313 (5795): 1914–1918. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1914F. doi:10.1126/science.1127889. PMID 17008522.

- "Circadian Rhythms Fact Sheet". National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- Nilsson, Dan-E. (1989). "Vision optics and evolution". BioScience. 39 (5): 298–307. doi:10.2307/1311112. JSTOR 1311112.

- Speiser, D.I.; Eernisse, D.J.; Johnsen, S.N. (2011). "A Chiton Uses Aragonite Lenses to Form Images". Current Biology. 21 (8): 665–670. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.033. PMID 21497091.

- Wilson, M. (1978). "The functional organisation of locust ocelli". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 124 (4): 297–316. doi:10.1007/BF00661380.

- Wagner, H.J.; Douglas, R.H.; Frank, T.M.; Roberts, N.W. & Partridge, J.C. (Jan 27, 2009). "A Novel Vertebrate Eye Using Both Refractive and Reflective Optics". Current Biology. 19 (2): 108–114. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.061. PMID 19110427.

- Völkel, R; Eisner, M; Weible, K.J (June 2003). "Miniaturized imaging systems" (PDF). Microelectronic Engineering. 67–68 (1): 461–472. doi:10.1016/S0167-9317(03)00102-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-01.

- Land, Michael (1997). "Visual Acuity in Insects" (PDF). Annual Review of Entomology. 42: 147–177. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.147. PMID 15012311. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2004. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- Gaten, Edward (1998). "Optics and phylogeny: is there an insight? The evolution of superposition eyes in the Decapoda (Crustacea)". Contributions to Zoology. 67 (4): 223–236. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- Ritchie, Alexander (1985). "Ainiktozoon loganense Scourfield, a protochordate from the Silurian of Scotland". Alcheringa. 9 (2): 137. doi:10.1080/03115518508618961.

- Mayer, G. (2006). "Structure and development of onychophoran eyes: What is the ancestral visual organ in arthropods?". Arthropod Structure and Development. 35 (4): 231–245. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2006.06.003. PMID 18089073.

- Meyer-Rochow, VB; Gal, J (2004). "Dimensional limits for arthropod eyes with superposition optics". Vision Research. 44 (19): 2213–2223. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2004.04.009. PMID 15208008.

- Greiner, Birgit (16 December 2005). Adaptations for nocturnal vision in insect apposition eyes (PDF) (PhD). Lund University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Horváth, Gábor; Clarkson, Euan N.K. (1997). "Survey of modern counterparts of schizochroal trilobite eyes: Structural and functional similarities and differences". Historical Biology. 12 (3–4): 229–263. doi:10.1080/08912969709386565.

- Jochen Zeil; Maha M. Al-Mutairi (1996). "Variations in the optical properties of the compound eyes of Uca lactea annulipes" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 199 (7): 1569–1577. PMID 9319471.

- Müller, CHG; Rosenberg, J; Richter, S; Meyer-Rochow, VB (2003). "The compound eye of Scutigera coleoptrata (Linnaeus, 1758) (Chilopoda; Notostigmophora): an ultrastructural re-investigation that adds support to the Mandibulata concept". Zoomorphology. 122 (4): 191–209. doi:10.1007/s00435-003-0085-0.

- Ullrich-Luter, E.M.; Dupont, S.; Arboleda, E.; Hausen, H.; Arnone, M.I. (2011). "Unique system of photoreceptors in sea urchin tube feet". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (20): 8367–8372. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8367U. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018495108. PMC 3100952. PMID 21536888.

- Ali & Klyne 1985, p. 8

- Autrum, H (1979). "Introduction". In H. Autrum (ed.). Comparative Physiology and Evolution of Vision in Invertebrates- A: Invertebrate Photoreceptors. Handbook of Sensory Physiology. VII/6A. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 4, 8–9. ISBN 978-3-540-08837-0.

- Halder, G.; Callaerts, P.; Gehring, W.J. (1995). "New perspectives on eye evolution". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 5 (5): 602–609. doi:10.1016/0959-437X(95)80029-8. PMID 8664548.

- Halder, G.; Callaerts, P.; Gehring, W.J. (1995). "Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila". Science. 267 (5205): 1788–1792. Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1788H. doi:10.1126/science.7892602. PMID 7892602.

- Tomarev, S.I.; Callaerts, P.; Kos, L.; Zinovieva, R.; Halder, G.; Gehring, W.; Piatigorsky, J. (1997). "Squid Pax-6 and eye development". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94 (6): 2421–2426. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.2421T. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.6.2421. PMC 20103. PMID 9122210.

- Conway-Morris, S. (1998). The Crucible of Creation. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Trevor D. Lamb; Shaun P. Collin; Edward N. Pugh Jr. (2007). "Evolution of the vertebrate eye: opsins, photoreceptors, retina and eye cup". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 8 (12): 960–976. doi:10.1038/nrn2283. PMC 3143066. PMID 18026166.

- Staaislav I. Tomarev; Rina D. Zinovieva (1988). "Squid major lens polypeptides are homologous to glutathione S-transferases subunits". Nature. 336 (6194): 86–88. Bibcode:1988Natur.336...86T. doi:10.1038/336086a0. PMID 3185725.

- "Eye-Evolution?". Library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-09-01.

- Fernald, Russell D. (2001). The Evolution of Eyes: Where Do Lenses Come From? Archived 2006-03-19 at the Wayback Machine Karger Gazette 64: "The Eye in Focus".

- Land, M.F. (1989). "The eyes of hyperiid amphipods: relations of optical structure to depth". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 164 (6): 751–762. doi:10.1007/BF00616747.

- Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (1982). "The divided eye of the isopod Glyptonotus antarcticus: effects of unilateral dark adaptation and temperature elevation". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. B 215 (1201): 433–450. Bibcode:1982RSPSB.215..433M. doi:10.1098/rspb.1982.0052.

- Ali & Klyne 1985, p. 28

- Russ, John C. (2006). The Image Processing Handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-7254-4. OCLC 156223054.

The upper limit (finest detail) visible with the human eye is about 50 cycles per degree,... (Fifth Edition, 2007, Page 94)

- Klaassen, Curtis D. (2001). Casarett and Doull's Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-134721-1. OCLC 47965382.

- "The Retina of the Human Eye". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu.

- Fischer, Robert E.; Tadic-Galeb, Biljana; Plympton, Rick (2000). Steve Chapman (ed.). Optical System Design. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-134916-1. OCLC 247851267.

- Barlow, H.B. (1952). "The size of ommatidia in apposition eyes". J Exp Biol. 29 (4): 667–674.

- Ali & Klyne 1985, p. 161

- Barlow, Horace Basil; Mollon, J.D (1982). The Senses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-24474-9.

- Fernald, Russell D. (1997). "The Evolution of Eyes" (PDF). Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 50 (4): 253–259. doi:10.1159/000113339. PMID 9310200.

- Goldsmith, T.H. (1990). "Optimization, Constraint, and History in the Evolution of Eyes". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 65 (3): 281–322. doi:10.1086/416840. JSTOR 2832368. PMID 2146698.

- Nilsson, E.; Arendt, D. (Dec 2008). "Eye Evolution: the Blurry Beginning". Current Biology. 18 (23): R1096–R1098. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.025. PMID 19081043.

Bibliography

- Ali, Mohamed Ather; Klyne, M.A. (1985). Vision in Vertebrates. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-42065-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Yong, Ed (14 January 2016). "Inside the Eye: Nature's Most Exquisite Creation". National Geographic.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eyes. |

- Evolution of the eye

- Anatomy of the eye – flash animated interactive. (Adobe Flash)

- Webvision. The organisation of the retina and visual system. An in-depth treatment of retinal function, open to all but geared most towards graduate students.

- Eye strips images of all but bare essentials before sending visual information to the brain, UC Berkeley research shows