Simple eye in invertebrates

A simple eye (sometimes called a pigment pit[1][2]) refers to a form of eye or an optical arrangement composed of a single lens and without an elaborate retina such as occurs in most Vertebrata. In this sense "simple eye" is distinct from a multi-lensed "compound eye", and is not necessarily at all simple in the usual sense of the word. The terminology is not rigid, and must be interpreted in proper context; for example, the eyes of humans and of other large animals such as most Cephalopoda, are camera eyes and in some usages are classed as "simple" because a single lens collects and focuses light onto the retina or film. By other criteria, the presence of a complex retina distinguishes the vertebrate camera eye from the simple stemma or ommatidium. Additionally not all ocelli and ommatidia of invertebrates have simple photoreceptors; many, including the ommatidia of most insects and the central eyes of Solifugae have various forms of retinula, and the Salticidae and some other predatory spiders with apparently simple eyes, emulate retinal vision in various ways. Many insects with unambiguously compound eyes consisting of multiple lenses (up to tens of thousands), but achieve an effect similar to that of a camera eye in that each ommatidium lens focuses light onto a number of neighbouring retinulae.

The structure of an animal's eye is determined by the environment in which it lives, and the behavioural tasks it must fulfill to survive. Arthropods differ widely in the habitats in which they live, as well as their visual requirements for finding food or conspecifics, and avoiding predators. Consequently, an enormous variety of eye types are found in arthropods: they possess a wide variety of novel solutions to overcome visual problems or limitations.

Ocelli or eye spots

Some jellyfish, sea stars, flatworms, and ribbonworms [3] bear the simplest eyes, pigment spot ocelli, which have pigment distributed randomly and which have no additional structures such as a cornea and lens. The apparent eye color in these animals is therefore red or black.[4] However, other cnidaria have more complex eyes, including those of Cubomedusae which have distinct retina, lens, and cornea.[5]

Many snails and slugs (gastropod mollusks) also have ocelli, either at the tips or at the bases of the tentacles.[6] However, some other gastropods, such as the Strombidae, have much more sophisticated eyes. Giant clams (Tridacna) have ocelli that allow light to penetrate their mantles.[7]

Simple eyes in arthropods

Spider eyes

Spiders do not have compound eyes, but instead have several pairs of simple eyes with each pair adapted for a specific task or tasks. The principal and secondary eyes in spiders are arranged in four or more pairs. Only the principal eyes have moveable retinas. The secondary eyes have a reflector at the back of the eyes. The light-sensitive part of the receptor cells is next to this, so they get direct and reflected light. In hunting or jumping spiders, for example, a forward-facing pair possesses the best resolution (and even telescopic components) to see the (often small) prey at a large distance. Night-hunting spiders' eyes are very sensitive in low light levels with a large aperture, f/0.58.[8]

Dorsal ocelli

The term "ocellus" (plural ocelli) is derived from the Latin oculus (eye), and literally means "little eye". Two distinct ocellus types exist:[9] dorsal ocelli (or simply "ocelli"), found in most insects, and lateral ocelli (or stemmata), which are found in the larvae of some insect orders. They are structurally and functionally very different. Simple eyes of other animals, e.g. cnidarians, may also be referred to as ocelli, but again the structure and anatomy of these eyes is quite distinct from those of the dorsal ocelli of insects.

Dorsal ocelli are light-sensitive organs found on the dorsal (top-most) surface or frontal surface of the head of many insects, e.g. Hymenoptera (bees, ants, wasps, sawflies), Diptera (flies), Odonata (dragonflies, damselflies), Orthoptera (grasshoppers, locusts) and Mantodea (mantises). The ocelli coexist with the compound eyes; thus, most insects possess two anatomically separate and functionally different visual pathways.

The number, forms, and functions of the dorsal ocelli vary markedly throughout insect orders. They tend to be larger and more strongly expressed in flying insects (particularly bees, wasps, dragonflies and locusts), where they are typically found as a triplet. Two lateral ocelli are directed to the left and right of the head, respectively, while a central (median) ocellus is directed frontally. In some terrestrial insects (e.g. some ants and cockroaches), only two lateral ocelli are present: the median ocellus is absent. The unfortunately labelled "lateral ocelli" here refers to the sideways-facing position of the ocelli, which are of the dorsal type. They should not be confused with the lateral ocelli of some insect larvae (see stemmata).

A dorsal ocellus consists of a lens element (cornea) and a layer of photoreceptors (rod cells). The ocellar lens may be strongly curved (e.g. bees, locusts, dragonflies) or flat (e.g. cockroaches). The photoreceptor layer may (e.g. locusts) or may not (e.g. blowflies, dragonflies) be separated from the lens by a clear zone (vitreous humour). The number of photoreceptors also varies widely, but may number in the hundreds or thousands for well-developed ocelli.

Two somewhat unusual features of the ocelli are particularly notable and generally well conserved between insect orders.

- The refractive power of the lens is not typically sufficient to form an image on the photoreceptor layer.

- Dorsal ocelli ubiquitously have massive convergence ratios from first-order (photoreceptor) to second-order neurons.

These two factors have led to the conclusion that the dorsal ocelli are incapable of perceiving form, and are thus solely suitable for light-metering functions. Given the large aperture and low f-number of the lens, as well as high convergence ratios and synaptic gains, the ocelli are generally considered to be far more sensitive to light than the compound eyes. Additionally, given the relatively simple neural arrangement of the eye (small number of synapses between detector and effector), as well as the extremely large diameter of some ocellar interneurons (often the largest diameter neurons in the animal's nervous system), the ocelli are typically considered to be "faster" than the compound eyes.[10]

One common theory of ocellar function in flying insects holds that they are used to assist in maintaining flight stability. Given their underfocused nature, wide fields of view, and high light-collecting ability, the ocelli are superbly adapted for measuring changes in the perceived brightness of the external world as an insect rolls or pitches around its body axis during flight. Corrective flight responses to light have been demonstrated in locusts[11] and dragonflies[12] in tethered flight. Other theories of ocellar function have ranged from roles as light adaptors or global excitatory organs to polarization sensors and circadian entrainers.

Recent studies have shown the ocelli of some insects (most notably the dragonfly, but also some wasps) are capable of form vision, as the ocellar lens forms an image within, or close to, the photoreceptor layer.[13][14] In dragonflies it has been demonstrated that the receptive fields of both the photoreceptors[15] and the second-order neurons[16] can be quite restricted. Further research has demonstrated these eyes not only resolve spatial details of the world, but also perceive motion.[17] Second-order neurons in the dragonfly median ocellus respond more strongly to upwards-moving bars and gratings than to downwards-moving bars and gratings, but this effect is only present when ultraviolet light is used in the stimulus; when ultraviolet light is absent, no directional response is observed. Dragonfly ocelli are especially highly developed and specialised visual organs, which may support the exceptional acrobatic abilities of these animals.

Research on the ocelli is of high interest to designers of small unmanned aerial vehicles. Designers of these craft face many of the same challenges that insects face in maintaining stability in a three-dimensional world. Engineers are increasingly taking inspiration from insects to overcome these challenges.[18]

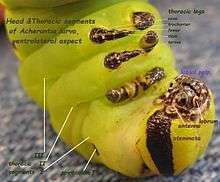

Stemmata

.jpg)

Stemmata (singular stemma) are a class of simple eyes. Many kinds of holometabolous larvae bear no other form of eyes until they enter their final stage of growth. Adults of several orders of hexapods also have stemmata, and never develop compound eyes at all. Examples include fleas, springtails, and Thysanura. Some other Arthropoda, such as some Myriapoda, rarely have any eyes other than stemmata at any stage of their lives (exceptions include the large and well-developed compound eyes of Scutigera [19].)

Behind each lens of a typical, functional stemma, lies a single cluster of photoreceptor cells, termed a retinula. The lens is biconvex, and the body of the stemma has a vitreous or crystalline core.

Although stemmata are simple eyes, some kinds, such as those of the larvae of Lepidoptera and especially those of Tenthredinidae, a family of sawflies, are only simple in that they represent immature or embryonic forms of the compound eyes of the adult. They can possess a considerable degree of acuity and sensitivity, and can detect polarized light.[20] In the pupal stage, such stemmata develop into fully fledged compound eyes. One feature offering a clue to their ontogenetic role is their lateral position on the head; ocelli, that in other ways resemble stemmata, tend to be borne in sites median to the compound eyes, or nearly so. In some circles this distinction has led to the use of the term "lateral ocelli" for stemmata.[9]

Genetic controls

A number of genetic pathways are responsible for the occurrence and positioning of the ocelli. The gene orthodenticle is allelic to ocelliless, a mutation that stops ocelli from being produced.[21] In Drosophila, the rhodopsin Rh2 is only expressed in simple eyes.[22]

While (in Drosophila at least) the genes eyeless and dachshund are both expressed in the compound eye but not the simple eye, no reported 'developmental' genes are uniquely expressed in the simple eye.[23]

Epidermal growth factor receptor (Egfr) promotes the expression of orthodenticle [and possibly eyes absent (Eya) and as such is essential for simple eye formation.[23]

References

- "Catalog - Mendeley". www.mendeley.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- O'Connor M, Nilsson DE, Garm A (March 2010). "Temporal properties of the lens eyes of the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora". J. Comp. Physiol. A. 196 (3): 213–20. doi:10.1007/s00359-010-0506-8. PMC 2825319. PMID 20131056.

- Meyer-Rochow VB; Reid WA (1993). "Cephalic structures in the Antarctic nemertine Parborlasia corrugatus - are they really eyes?". Amer Tissue & Cell. 25 (1): 151–157. doi:10.1016/0040-8166(93)90072-S. PMID 18621228.

- "Eye (invertebrate)". McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. 6. 2007. p. 790.

- Vicki J. Martin (2002). "Photoreceptors of cnidarians" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-05.

- Zieger V, Meyer-Rochow VB (2008). "Understanding the Cephalic Eyes of Pulmonate Gastropods: A Review". American Malacological Bulletin. 26 (1–2): 47–66. doi:10.4003/006.026.0206.

- Murphy, Richard C. (2002). Coral Reefs: Cities Under The Seas. The Darwin Press, Inc. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-87850-138-0.

- Blest, AD; Land (1997). "The Physiological optics of Dinopis Subrufus L.Koch: a fisheye lens in a spider". Proceedings of the Royal Society (196): 198–222.

- C. Bitsch & J. Bitsch (2005). "Evolution of eye structure and arthropod phylogeny". In Stefan Koenemann & Ronald Jenner (eds.). Crustacea and Arthropod Relationships. Volume 16 of Crustacean Issues. Taylor & Francis. pp. 185–214. ISBN 978-0-8493-3498-6.

- Martin Wilson (1978). "The functional organisation of locust ocelli". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 124 (4): 297–316. doi:10.1007/BF00661380.

- Charles P. Taylor (1981). "Contribution of compound eyes and ocelli to steering of locusts in flight: I. Behavioural analysis". Journal of Experimental Biology. 93 (1): 1–18. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25.

- Gert Stange & Jonathon Howard (1979). "An ocellar dorsal light response in a dragonfly". Journal of Experimental Biology. 83 (1): 351–355. Archived from the original on 2007-12-17.

- Eric J. Warrant, Almut Kelber, Rita Wallén & William T. Wcislo (December 2006). "Ocellar optics in nocturnal and diurnal bees and wasps". Arthropod Structure & Development. 35 (4): 293–305. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2006.08.012. PMID 18089077.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Richard P. Berry, Gert Stange & Eric J. Warrant (May 2007). "Form vision in the insect dorsal ocelli: an anatomical and optical analysis of the dragonfly median ocellus". Vision Research. 47 (10): 1394–1409. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2007.01.019. PMID 17368709.

- Joshua van Kleef, Andrew Charles James & Gert Stange (October 2005). "A spatiotemporal white noise analysis of photoreceptor responses to UV and green light in the dragonfly median ocellus". Journal of General Physiology. 126 (5): 481–497. doi:10.1085/jgp.200509319. PMC 2266605. PMID 16260838.

- Richard Berry, Joshua van Kleef & Gert Stange (May 2007). "The mapping of visual space by dragonfly lateral ocelli". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 193 (5): 495–513. doi:10.1007/s00359-006-0204-8. PMID 17273849.

- Joshua van Kleef, Richard Berry & Gert Stange (March 2008). "Directional selectivity in the simple eye of an insect". The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (11): 2845–2855. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5556-07.2008. PMC 6670670. PMID 18337415.

- Gert Stange, R. Berry & J. van Kleef (September 2007). Design concepts for a novel attitude sensor for Micro Air Vehicles, based on dragonfly ocellar vision. 3rd US-European Competition and Workshop on Micro Air Vehicle Systems (MAV07) & European Micro Air Vehicle Conference and Flight Competition (EMAV2007). 1. pp. 17–21.

- Müller, CHG; Rosenberg, J; Richter, S; Meyer-Rochow, VB (2003). "The compound eye of Scutigera coleoptrata (Linnaeus, 1758) (Chilopoda; Notostigmophora): an ultrastructural re-investigation that adds support to the Mandibulata concept". Zoomorphology. 122 (4): 191–209. doi:10.1007/s00435-003-0085-0. S2CID 6466405.

- Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (1974). "Structure and function of the larval eye of the sawfly Perga". Journal of Insect Physiology. 20 (8): 1565–1591. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(74)90087-0. PMID 4854430.

- R. Finkelstein, D. Smouse, T. M. Capaci, A. C. Spradling & N Perrimon (1990). "The orthodenticle gene encodes a novel homeo domain protein involved in the development of the Drosophila nervous system and ocellar visual structures". Genes & Development. 4 (9): 1516–1527. doi:10.1101/gad.4.9.1516. PMID 1979296.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Adriana D. Briscoe & Lars Chittka (2001). "The evolution of color vision in insects". Annual Review of Entomology. 46: 471–510. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.471. PMID 11112177.

- Markus Friedrich (2006). "Ancient mechanisms of visual sense organ development based on comparison of the gene networks controlling larval eye, ocellus, and compound eye specification in Drosophila". Arthropod Structure & Development. 35 (4): 357–378. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2006.08.010. PMID 18089081.

Further reading

- Warrant, Eric; Nilsson, Dan-Eric (2006). Invertebrate Vision. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83088-1.

External links

- John R. Meyer, Photoreceptors

.jpg)