Ed Ricketts

Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts (May 14, 1897 – May 11, 1948) commonly known as Ed Ricketts, was an American marine biologist, ecologist, and philosopher. He is best known for Between Pacific Tides (1939), a pioneering study of intertidal ecology, and for his influence on writer John Steinbeck, which resulted in their collaboration on the Sea of Cortez (1941), later republished as The Log from the Sea of Cortez (1951).

Ed Ricketts | |

|---|---|

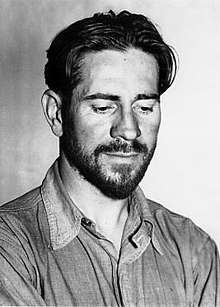

Ricketts in 1937 | |

| Born | May 14, 1897 |

| Died | May 11, 1948 (aged 50) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Between Pacific Tides |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Marine biology |

Life

Ricketts was born in Chicago, Illinois, to Abbott Ricketts and Alice Beverly Flanders Ricketts. He had a younger sister, Frances, and a younger brother, Thayer. His sister, Frances (Ricketts) Strong, said of him that he had a mind like a dictionary and was often in trouble for correcting teachers and other adults.[1] Ricketts spent most of his childhood in Chicago, except for a year in South Dakota when he was ten years old.

After a year of college, Ricketts traveled to Texas and New Mexico. In 1917 he was drafted into the Army Medical Corps. He hated the military bureaucracy but, according to John Steinbeck, "was a successful soldier."

After discharge from the army, Ricketts studied zoology at the University of Chicago. He was influenced by his professor, W. C. Allee,[1] but dropped out without taking a degree. He then spent several months walking through the American south, from Indiana to Florida. He used material from this trip to publish an article in Travel magazine titled "Vagabonding Through Dixie." He returned to Chicago and studied some more at the university.[1]

In 1922 Ricketts met and married Anna Barbara Maker, whom he called "Nan." A year later they had a son, Edward F. Ricketts, Jr., and moved to California to set up Pacific Biological Laboratories with Albert E. Galigher: Galigher was Ricketts' college friend with whom he had run a similar business on a smaller scale. In 1924 Ricketts became sole owner of the lab, and soon two daughters were born: Nancy Jane on 28 November 1924, and Cornelia on 6 April 1928.

Between 1925 and 1927, Ricketts' sister Frances and both his parents moved to California; Frances and their father Abbott worked with Ricketts at the lab. In late 1930 Ricketts met aspiring writer John Steinbeck and his wife Carol,[1] who had moved to Pacific Grove earlier in the year. For more than a year Carol worked half-time for Ricketts at the lab, until 1932 when Ricketts' wife Nan left, taking their two daughters, and Ricketts no longer had enough money to pay Carol's salary. Steinbeck himself also spent time at the lab, learning marine biology, helping Ricketts preserve specimens and talking about philosophy. Steinbeck lived very near the lab. What kept them together was the discovery that each had an almost boundless curiosity about almost everything, and that their personality meshed so well. Steinbeck had a need to give, and Ricketts a need to receive. Ricketts made listening an art. At one point in Steinbeck's life, he suffered an "overwhelming emotional upset", and went to the lab to stay with Ricketts. Ricketts played music for Steinbeck until he could bear to come back to himself.[2]

Nan's separation from Ricketts in 1932 was the first of many separations. In 1936 Ricketts and Nan separated for good, and he took up residence in his lab. On 25 November 1936, a fire spread from the adjacent cannery, destroying the lab. Ricketts lost nearly everything, including an extraordinary amount of correspondence, research notes, manuscripts, and his prized library, which had held everything from invaluable scientific resources to his beloved collection of poetry. However, the manuscript of Ricketts' textbook (with Jack Calvin) Between Pacific Tides had already been sent to the publisher.[1] John Steinbeck would become a silent 50% partner in the lab, after funding its reconstruction costs.

In 1940 Ricketts and Steinbeck journeyed to the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California) in a chartered fishing boat to collect invertebrates for the scientific catalog in their book, Sea of Cortez. Also in 1940, Ricketts began a relationship with Eleanor Susan Brownell Anthony "Toni" Solomons Jackson, who became his common-law wife.[3][4][5][6] As Steinbeck's secretary, Jackson helped edit The Log From the Sea of Cortez. Jackson, who had attended the University of California, Los Angeles, was the daughter of Katherine Gray Church[7][8] and Theodore Solomons, an explorer and early member of the Sierra Club, who had discovered and defined the John Muir Trail.[9] Jackson and her young daughter Katherine Adele moved in with Ricketts and lived with him until 1947. In addition to Steinbeck, their circle of friends included the novelist and painter Henry Miller and the mythologist, writer, and lecturer Joseph Campbell.[10]

During World War II, Ricketts again served in the Army, this time as a medical lab technician; he was drafted in October 1942, missing the age cut-off by days. During his service, he kept collecting marine life and compiling data. His son was drafted in 1943.

In 1945, Steinbeck's novel Cannery Row was published. Ricketts, the model for "Doc," became a celebrity, and tourists and journalists began seeking him out. Steinbeck portrayed "Doc" (and thus, Ricketts) as a many-faceted intellectual who was somewhat outcast from intellectual circles, a party-loving drinking man, in close touch with the working class and with the prostitutes and bums of Monterey's Cannery Row. Steinbeck wrote of "Doc": "He wears a beard and his face is half Christ and half satyr and his face tells the truth."[11]

Ricketts himself read Cannery Row with exasperation, by all accounts, but ended saying simply that it could not be criticized because it had not been written with malice.[12] Ricketts was also portrayed as "Doc" in Sweet Thursday, the sequel to Cannery Row; as "Friend Ed" in Burning Bright; as "Doc Burton" in In Dubious Battle; as Jim Casy in The Grapes of Wrath; and as "Doctor Winter" in The Moon is Down.

In September 1946, Ricketts' daughter Nancy Jane had a son, making Ricketts a grandfather. That same year, his stepdaughter Kay's health deteriorated due to a brain tumor; she died the following year, on 5 October 1947. Kay's mother, Toni left Ricketts shortly afterwards.

Just a few weeks later, Ricketts met Alice Campbell, a music and philosophy student half his age. They "married" in early 1948, though the marriage was not valid because Ricketts had never legally divorced Nan.

In March 1948 in New York City, Toni Jackson married Dr Benjamin Elazari Volcani,[13] a renowned microbiologist she had met while he was working with the famous microbiologist C. B. van Niel (a student of Albert Kluyver's) at Stanford University's Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey in 1943.

In 1948, Ricketts and Steinbeck planned together to go to British Columbia and write another book, The Outer Shores, on the marine life north towards Alaska.[1] On previous trips Ricketts had already done most of the needed research and he gave Steinbeck the typescripts for these as he had done previously with The Sea of Cortez.[14]

A week before the planned expedition, on 8 May 1948, as Ricketts was driving across the railroad tracks at Drake Avenue, just uphill from Cannery Row, on his way to dinner after his day's work, a Del Monte Express (passenger train) hit his car.[15][16] He lived for three days, conscious at least some of the time, before dying on May 11.

A life-size bust of Ricketts, at the site of the long-defunct rail crossing, commemorates the biologist-philosopher who inspired novelist John Steinbeck and mythologist Joseph Campbell. Passers-by often pick nearby flowers and place them in the statue's hand. Also at the crossing are derelict crossbucks marking the site of the accident.

Lab

In 1923, Ed Ricketts and his business partner Albert Galigher started Pacific Biological Laboratories (PBL), a marine biology supply house. The lab was located in Pacific Grove at 165 Fountain Avenue.[17] The business was later moved to 740 Ocean View Avenue, Monterey, California, with Ricketts as sole owner. Today, that location is 800 Cannery Row.

On 25 November 1936, a fire broke out at the Del Mar Cannery next to the lab. Most of the laboratory's contents were destroyed. The typescript of Between Pacific Tides survived, as it had already been sent to Stanford University for publication. With an investment from John Steinbeck, who became silent partner and 50% owner of the business as a result, Ricketts rebuilt the lab using the original floorplan.

Ricketts' lab on Cannery Row had attracted visitors who ran the gamut from writers, artists and musicians to prostitutes and bums. Gatherings often included discussions of philosophy, science and art, and sometimes developed into parties that continued for days.[15] Participants in meetings had included Steinbeck, Bruce Ariss, Joseph Campbell (who had worked at the lab as Ricketts' assistant), Adelle Davis,[18] Henry Miller, Lincoln Steffens and Francis Whitaker. Amidst the tumult of commercial activity and tourist attractions that Cannery Row has become in recent decades, the modest and mostly unnoticed and unmarked lab stands as a silent witness to the bygone era celebrated in Steinbeck's work.

Ricketts' laboratory business was fictionalized in Steinbeck's Cannery Row as "Western Biological Laboratories."[19]

Steinbeck was inspired to write The Pearl after visiting La Paz, Baja California Sur, with Ricketts on their Sea of Cortez expedition.

Philosophy

In addition to his writings on marine life, Ricketts wrote three philosophical essays; he continued to revise them over the years, integrating new ideas in response to feedback from Campbell, Miller, and other friends. The first essay lays out his idea of "nonteleological thinking" – a way of viewing things as they are, rather than seeking explanations for them. In his second essay, "The Spiritual Morphology of Poetry," he proposed four progressive classes of poetry, from naive to transcendent, and assigned famous poets from Keats to Whitman to these categories. The third essay, "The Philosophy of 'Breaking Through'," explores transcendence throughout the arts and describes his own moments of 'breaking through', such as his first hearing of Madame Butterfly.[20]

According to his letters, conversations with composer John Cage helped Ricketts clarify some of his thoughts on poetry, and gave him new insight into the emphasis on form over content embraced by many modern artists.

Even though Steinbeck presented the essays to various publishers on behalf of Ricketts, only one was ever published in his lifetime: the first essay appears (without attribution) in a chapter titled "Non-Teleological Thinking" in The Log From the Sea of Cortez. All of his major essays, along with other shorter works were published in The Outer Shores, vols. 1 and 2, edited by Joel Hedgpeth, and with additional biographical commentary also by Hedgpeth. Much of this material appears in Katharine Rodger's book, Breaking Through: Essays, Journals, and Travelogues of Edward F. Ricketts (2006).

.png)

In the 1930s and 1940s, Ricketts strongly influenced many of Steinbeck's writings. The biologist inspired a number of notable characters in Steinbeck's novels, and ecological themes recur in them. Ricketts' biographer Eric Enno Tamm notes that, except for East of Eden (1952), Steinbeck's writing declined after Ricketts' death in 1948.[15]

Ricketts also influenced the mythologist Joseph Campbell. This was an important period in the development of Campbell's thinking about the epic journey of "the hero with a thousand faces." Campbell lived for a while next door to Ricketts, participated in professional and social activities at his neighbor's, and accompanied him, along with Xenia and Sasha Kashevaroff, on a 1932 journey to Juneau, Alaska, on the Grampus.[21] Like Steinbeck, Campbell played with a novel written round Ricketts as hero, but unlike Steinbeck, didn't complete the book.[22] Bruce Robison writes that "Campbell would refer to those days as a time when everything in his life was taking shape.... Campbell, the great chronicler of the "hero's journey" in mythology, recognized patterns that paralleled his own thinking in one of Ricketts's unpublished philosophical essays. Echoes of Carl Jung, Robinson Jeffers and James Joyce can be found in the work of Steinbeck and Ricketts as well as Campbell."[15]

Henry Miller wrote about Ricketts in his book The Air-Conditioned Nightmare: [Ed Ricketts is] "a most exceptional individual in character and temperament, a man radiating peace, joy and wisdom" and said that Ricketts was (apart from L. C. Powell) the only person whom Miller, during his journey across USA, found being "satisfied with his lot, adjusted to his environment, happy in his work, and representative of all that is best in the American tradition." [23]

Ecology

In Ricketts' day, ecology was early in its development. Now-common concepts such as habitat, niche, succession, predator-prey relationships, and food chains were not yet mature ideas. Ricketts was among a few marine biologists who studied intertidal organisms in an ecological context.

His first major scientific work — now regarded as a classic in marine ecology, and in its fifth edition — was Between Pacific Tides, published in 1939, co-authored with Jack Calvin. The third and fourth editions were revised by Joel Hedgpeth, a contemporary of Ricketts and Steinbeck; Hedgpeth continued the book's taxonomic excellence, while retaining its ecological approach.

The pioneering nature of Ricketts' book may be appreciated by comparison with another classic work, now in its fourth edition, that was published two years later, in 1941: Light's Manual, by S. F. Light, of the University of California, Berkeley. Light's Manual is technical, difficult for laymen, but essential for specialists. On the other hand, Ricketts' Between Pacific Tides is readable, full of observations and side comments, and readily accessible to anyone with a genuine interest in seashore life. It cannot serve as a thorough manual to marine invertebrates, but it addresses the common and conspicuous animals in a style that invites and educates newcomers and offers substantial information for experienced biologists. It is not organized according to taxonomic classification, but instead by habitat. Thus, crabs are not all treated in the same chapter; crabs of the rocky shore, high in the intertidal, are in a separate section from crabs of lower intertidal zones or sandy beaches.

Some concepts that Ricketts used in Between Pacific Tides were novel then and ignored by some in academia. Ricketts, writes Bruce Robison of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, "was 'a lone, largely marginalized scientist' with no university degrees, and he had to struggle... against... traditionalists" to get the book published by Stanford University Press.[15]

Ricketts' subsequent book, Sea of Cortez, is almost two separate books. The first section is a narrative, co-written by Steinbeck and Ricketts (Ricketts kept a daily journal during the expedition; Steinbeck edited the journal into the narrative section of the book). Later, the narrative was published alone as The Log From the Sea of Cortez, without Ricketts's name. The remainder of the book, about 300 pages, is an "Annotated Phyletic Catalog" of specimens collected. This section was Ricketts' work alone. It was presented in the traditional taxonomic arrangement, but with numerous notes on ecological observations.

Ricketts pursued pathfinding studies in quantitative ecology, analyzing the Monterey sardine fishery. In a 1947 article in the Monterey Peninsula Herald, he documented sardine harvests, described sardine ecology, and noted that harvests were declining as fishing intensity increased. When the sardines became depleted and the industry was destroyed, Ricketts explained what had happened to the sardines: "They're in cans."[24]

The research Ricketts did on sardines was a seminal application of ecology to fisheries science, but it was not published as an academic paper. He is not widely recognized by fisheries scientists. The prominent fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly comments: “That’s probably due to the fact that his stuff isn’t widely available... This is strange, but fisheries scientists so far as they are trained do extraordinarily little ecology... I will not publish a paper on pelagics without now mentioning Ricketts”.[25]

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute deploys a four kilometer depth rated remotely operated vehicle named in honor of Ricketts's work, the ROV Doc Ricketts.[26]

Eponymous species

Since 1930, over 16 species have been named after Ricketts:[27]

- Aclesia rickettsi (Sea slug)

- Catriona rickettsi (Sea slug)

- Hypsoblenniops rickettsi (Blenny)

- Longiprostatum rickettsi (Flatworm)

- Mysidium rickettsi (Opossum shrimp)

- Siphonides rickettsi (Peanut worm)

- Nephtys rickettsi (Polychaete worm)

- Mesochaetopterus rickettsi (Polychaete worm)

- Polydora rickettsi Woodwick 1961 (Polychaete worm)

- Panoploea rickettsi (Sand flea)

- Pentactinia rickettsi (Sea anemone)

- Palythoa rickettsi (Zoanthid)

- Isometridium rickettsi (Sea anemone)

- Pycnogonum rickettsi Schmitt, 1934 (Sea spider)

- Asbestopluma rickettsi Lundsten et al., 2014 (Sea sponge)[28]

- Poecillastra rickettsi (Sea sponge)

- Acorylus rickettsi Coan & Valentich-Scott, 2010 (Clam)

References

- Rodger, Katie (30 March 2012). Ed Ricketts, Between Pacific Tides, and Beyond Sitka Sound... (Speech). University of Alaska, Southeast. Sitka, Alaska.

- Benson 1990

- Williams, Jack (2006). "Obituary of Toni Volcani". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 2009-06-08.

- "Stern p.276" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- Railsback, Brian E.; Michael J. Meyer (2006). A John Steinbeck encyclopedia. Greenwood Publisher Group. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-313-29669-7.

- "SIO LOG #16". The Scripps Log. University of California, San Diego. 2006-05-20. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- Raymond, Marcius D (1887). Gray Genealogy. Higginson Book Company. p. 64.

- Jordan, John Woolf (1913). Genealogical and personal history of the Allegheny Valley, Pennsylvania. Lewis Historical Pub. Col. p. 372.

james patton newell.

- Winnett & Morey 2001, front paper

- Mavericks on Cannery Row American Scientist, Book review.

- See Tamm 2004, p. 292; Burkhead 2002, p. 91; Steinbeck 1994 [1945], Chapter V, p. 29

- Tamm, Eric Enno. Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist Who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell. Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004. ISBN 1-56858-298-6

- University of California (System) Academic Senate (2000). 2000, University of California: In Memoriam. University of California Regents. p. 283.

- Bruce Robison, "Mavericks on Cannery Row," American Scientist, vol. 92, no. 6 (November–December 2004, p. 1: a review of Eric Enno Tamm, Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell, Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004.

- Bruce Robison, "Mavericks on Cannery Row," American Scientist, vol. 92, no. 6 (November–December 2004, p. 1.

- Marquis Childs, "A Novel Aquarium Depicts the Story of Monterey Bay," Smithsonian, vol. 16, no. 6 (June 1985), p. 95.

- Seavey, Kent (2005). Pacific Grove. Arcadia Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7385-2964-6.

- "Joseph Campbell - Chronology". Archived from the original on 2008-12-27. Retrieved 2009-03-31. Campbell Chronology Accessed March 30, 2009

- McElrath, Joseph R.; Crisler, Jesse S.; Shillinglaw, Susan (1996). Pacific Grove. Cambridge University. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-521-41038-0.

- Bayuk, Kevin (2002) An Analysis of the Concept of Breaking Through Cannery Row Foundation.

- Straley, John (13 November 2011). "Sitka's Cannery Row Connection and the Birth of Ecological Thinking". 2011 Sitka WhaleFest Symposium: stories of our changing seas. Sitka, Alaska: Sitka WhaleFest.

- Tamm, Eric Enno (2005) Of myths and men in Monterey: "Ed Heads" see Doc Ricketts as a cult figure

- Henry Miller, The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, New Directions, 1945, pp. 18 - 19

- Early years and family info, pp. xv-xxii; daughters, pp. 111 and 199; WWII draft, p. 177; Separation from Nan, fire, p. xxxi; Toni and Kay, Alice, death, pp. xliv-lii; Nancy Jane's son, p. 237; Essay info, pp xxxii-xxxvii; John Cage reference, pp. 81-84 and p. 194. Ricketts, Edward Flanders. Rodger, Katharine A. (2003). Renaissance Man of Cannery Row: The Life and Letters of Edward F. Ricketts. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5087-X

- Ed Ricketts’ death, 50 years ago last week, preceded that of Cannery Row by only a few months. – Eric Enno Tamm (2005) Monterey County Weekly.

- Vessels and Vehicles - ROV Doc Ricketts Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

- Tamm 2005, p.243

- Lundsten et al., 2014, "Four new species of Cladorhizidae (Porifera, Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida) from the Northeast Pacific," Zootaxa 3786 (2): 101-123.

Sources

- Astro, Richard. (1973). John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: the Shaping of a Novelist. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0704-4

- Astro, Richard. (1976). Edward F. Ricketts. Western Writers Series No 21. Boise State Univ. ISBN 0-88430-020-X

- Benson, Jackson J., "John Steinbeck, Writer", Penguin Putnam Inc., NYC, 1990, ISBN 9780140144178

- Lannoo, Michael J. Leopold's Shack and Ricketts's Lab: The Emergence of Environmentalism (University of California Press; 2010) 196 pages; a combined study of Aldo Leopold and Ed Ricketts as major and parallel influences on environmentalism.

- Ricketts, Edward F. and Jack Calvin. (1939). Between Pacific Tides. Stanford University Press; 5th/Rev edition. 1992. ISBN 0-8047-2068-1

- Ricketts, Edward Flanders. Hedgpeth, Joel W. (ed). (1978). Outer Shores. Mad River Press. ISBN 0-916422-13-5

- Ricketts, Edward Flanders. Hedgpeth, Joel W. (ed). (1979). Outer Shores 2: Breaking Through. Mad River Press. ISBN 0-916422-14-3

- Ricketts, Edward Flanders. Rodger, Katharine A. (2003). Renaissance Man of Cannery Row: The Life and Letters of Edward F. Ricketts. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5087-X

- Robison, Bruce, "Mavericks on Cannery Row," American Scientist, vol. 92, no. 6 (November–December 2004, p. 1: a review of Eric Enno Tamm, Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell, Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004.

- Smith, R.I. and J. T. Carlton. 1975. Light's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02113-4

- Steinbeck, John. Ricketts, Edward F. (1941). Sea of Cortez: A leisurely journal of travel and research, with a scientific appendix comprising materials for a source book on the marine animals of the Panamic faunal province. Reprinted by Paul P Appel Pub. 1971. ISBN 0-911858-08-3

- Steinbeck, John. Shillinglaw, Susan (intro). (1994). Cannery Row. Penguin Classics; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-14-018737-5

- Steinbeck, John. Astro, Richard (intro). (1995). The Log from the Sea of Cortez. Penguin Classics; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-14-018744-8

- Tamm, Eric Enno (2005) Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-689-2.

- Winnett, Thomas; Morey, Kathy (2001). Guide to the John Muir Trail (Third ed.). Berkeley, CA: Wilderness Press. ISBN 978-0-89997-221-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ed Ricketts |

- National Public Radio (USA) piece on Ed Ricketts and the 'Dream' of Cannery Row

- Ecology Hall of Fame's biography of Ed Ricketts; contains several errors

- Website about the first biography on Ed Ricketts titled "Beyond the Outer Shores" by Eric Enno Tamm (cited above)

- California Views photography website,The Pat Hathaway Collection with good photos and brief biographical info

- Another California Views photography website, The Pat Hathaway Collection with good photos and brief biographical info

- San Francisco Chronicle article on plans to repeat the Ricketts / Steinbeck Sea of Cortez trip

- "Ed Heads", San Francisco Chronicle article on latter day Ricketts followers, written by Eric Tamm

- "The Science and Philosophy of Edward Flanders Robb Rickets", Stanford University website that identifies books in Ricketts' library, his collection cards, and sources that influenced him.