Xylitol

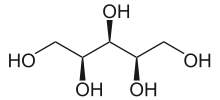

Xylitol is a chemical compound with the formula C

5H

12O

5, or HO(CH2)(CHOH)3(CH2)OH; specifically, one particular stereoisomer with that structural formula. It is a colorless or white crystalline solid that is soluble in water. It can be classified as a polyalcohol and a sugar alcohol, specifically an alditol. The name derives from Ancient Greek: ξύλον, xyl[on], "wood", with the suffix -itol used to denote sugar alcohols.

| |

Xylitol crystals | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈzaɪlɪtɒl/ |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R,3R,4S)-Pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol | |

| Other names

(2R,3R,4S)-Pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentaol (not recommended) 1,2,3,4,5-Pentahydroxypentane Xylite | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.626 |

| E number | E967 (glazing agents, ...) |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H12O5 | |

| Molar mass | 152.146 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.52 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 92 to 96 °C (198 to 205 °F; 365 to 369 K) |

| Boiling point | 345.39 °C (653.70 °F; 618.54 K) Predicted value using Adapted Stein & Brown method[2] |

| ~100 g/L | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Related compounds | |

Related alkanes |

Pentane |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Xylitol is used as a food additive and sugar substitute. Its European Union code number is E967.[3] Replacing sugar by xylitol in food products may promote better dental health, but evidence is lacking on whether xylitol itself prevents cavities.[4]

Structure, production, commerce

Xylitol is naturally occurring in small amounts in plums, strawberries, cauliflower, and pumpkin; humans and animals make trace amounts during metabolism of carbohydrates.[5] Unlike most sugar alcohols, xylitol is achiral.[6] Most other isomers of pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol are chiral, but xylitol has a plane of symmetry.

Industrial production starts with lignocellulosic biomass from which xylan is extracted; raw biomass materials include hardwoods, softwoods, and agricultural waste from processing maize, wheat, or rice. The xylan polymers can be hydrolyzed into xylose, which is catalytically hydrogenated into xylitol. The conversion changes the sugar (xylose, an aldehyde) into the primary alcohol, xylitol. Impurities are then removed.[5] The processing is often done using standard industrial methods; industrial fermentation involving bacteria, fungi, or yeast, especially Candida tropicalis, are common, but are not as efficient.[5][7]

According to the US Department of Energy, xylitol production by fermentation from discarded biomass is one of the most valuable renewable chemicals for commerce, forecast to be a US$1.4 billion industry by 2025.[8]

Uses

Xylitol is used as a sugar substitute in such manufactured products as drugs, dietary supplements, confections, toothpaste, and chewing gum, but is not a common household sweetener.[4][9] Xylitol has negligible effects on blood sugar because it is metabolized independently of insulin.[9] Absorbed more slowly than sugar, xylitol supplies 40% fewer calories than table sugar.[9] It is approved as a food additive in the United States.[10]

Food properties

Xylitol has about the same sweetness as sucrose,[9] but more sweetness than similar compounds like sorbitol and mannitol.[5] Xylitol is stable enough to be used in baking.[11] Because xylitol and other polyols are heat stable, they do not caramelise as sugars do, and they also lower the freezing point of mixtures in which they are used.[12]

No serious health risk exists in most humans for normal levels of consumption; The European Food Safety Authority has not set a limit on daily intake of xylitol. Due to the adverse laxative effect that all polyols have on the digestive system in high doses, xylitol is banned from soft drinks in the EU. Similarly due to a 1985 report, by the EU Scientific Committee on Food, stating that "ingesting 50 g a day of xylitol can cause diarrhea", tabletop sweeteners containing xylitol are required to display the warning: "excessive consumption may induce laxative effects".[13] Chewing gum containing xylitol is permitted.[14]

Health effects

Dental care

As of 2015, clinical trials examining whether xylitol alone or with other agents can prevent cavities found the evidence was too poor to allow generalizations, although when children with permanent teeth use fluoride toothpaste with xylitol, they may get fewer cavities than when using fluoride toothpaste without it.[4] Weak evidence indicates that chewing gum sweetened with xylitol (or similar polyols such as sorbitol) may reduce the incidence of cavities.[15][16][17]

In 2008, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that "xylitol chewing gum reduces the risk of cavities in children".[14] The claim was controversially recognised as requiring rewording in 2009 because xylitol chewing gum is not a medicine, thus can "not be claimed to reduce the risk of a disease".[18] In 2011, EFSA approved a claim that replacing sugar with xylitol and similar sweeteners "may maintain tooth mineralisation compared with sugar-containing foods."[13][19]

Ear aches

In 2011, EFSA "concluded that there was not enough evidence to support" the claim that xylitol-sweetened gum could prevent middle-ear infections with a fast onset, which is also known as acute otitis media (AOM).[13][20] A 2016 review indicated that xylitol in chewing gum or a syrup may have a moderate effect in preventing ear aches in healthy children.[21] It may be an alternative to conventional therapies (such as antibiotics) to lower risk of AOM in healthy children – reducing risk of occurrence by 25%[22] – although there is no definitive proof that it could be used as a therapy for AOM.[21]

Diabetes

In 2011, EFSA approved a marketing claim that foods or beverages containing xylitol or similar sugar replacers cause lower blood glucose and lower insulin responses compared to sugar-containing foods or drinks.[11][19] Xylitol products are used as sucrose substitutes for weight control,[11][23] as xylitol has 40 percent fewer calories than sucrose (2.4 kcal/g compared to 4.0 for sucrose).[11][24] The glycemic index (GI) of xylitol is 7 if GI is 100 for glucose.[25]

Adverse effects

Humans

Xylitol has no known toxicity in humans.[13] At high doses, xylitol and other polyols cause gastrointestinal discomfort, including flatulence, diarrhea, and irritable bowel syndrome (see metabolism section); some people have these adverse effects at lower doses.[13][26] Xylitol has a lower laxation threshold than some sugar alcohols but is more easily tolerated than mannitol and sorbitol.[27]

Increased xylitol consumption can increase oxalate, calcium and phosphate excretion to urine. These affects are termed oxaluria, calciuria and phosphaturia, respectively. These are risk factors for kidney stone disease, but xylitol ingestion has not been linked to this disease in humans.[28]

Dogs and other animals

In dogs, 100 mg of xylitol per kg of body weight (mg/kg bw) causes a dose-dependent insulin release that can result in hypoglycemia, which can be life-threatening. Hypoglycemia associated symptoms of xylitol toxicity may arise as quickly as 30 to 60 minutes after ingestion. Vomiting is a common first symptom. It can be followed by tiredness and ataxia. At doses above 500 mg/kg bw, liver failure is likely and may result in coagulopathies like disseminated intravascular coagulation.[29]

Xylitol is safe for cats, which tolerate even 1000 mg/kg bw ingested doses of it.[30] It is also safe for rhesus macaques, horses and rats.[29]

Metabolism

Xylitol has 2.4 kcal/g (10 kJ/mol) of food energy according to US and EU food labeling regulations.[31][3] The real value can vary, depending on metabolic factors. About 50% of eaten xylitol is not absorbed by the intestines in humans. Instead, 50–75% of this amount is fermented by gut bacteria to short-chain organic acids and gases, which may cause flatulence. The rest of the unabsorbed xylitol is excreted unchanged mostly in feces and less than 2 g of xylitol out of every 100 g ingested is excreted in urine.[32] Xylitol ingestion also increases motilin secretion, which may be related to xylitol's ability to cause diarrhea.[33] The non-digestible but fermentable nature of xylitol also contributes to constipation relieving effects.[23]

About 50% of xylitol is absorbed via intestines. Primarily, the liver metabolizes it. The main metabolic route in humans is: in cytoplasm, nonspecific NAD-dependent dehydrogenase (polyol dehydrogenase) transforms xylitol to D-xylulose. Specific xylulokinase phosphorylates it to D-xylulose-5-phosphate. This then goes to pentose phosphate pathway for further processing.[32]

History

Sugar rationing during World War II led to an interest in sugar substitutes. Interest in xylitol and other polyols became intense, leading to their characterization and manufacturing methods.[5][34]

References

- Safety data sheet for xylitol from Fisher Scientific. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- "Xylitol". Chemspider. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- "Food – EPA – European Association of Polyol Producers". polyols-eu.org. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- Riley, P; Moore, D; Ahmed, F; Sharif, MO; Worthington, HV (26 March 2015). "Xylitol-containing products for preventing dental caries in children and adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD010743. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010743.pub2. PMID 25809586. Lay summary.

- Ur-Rehman, S; Mushtaq, Z; Zahoor, T; Jamil, A; Murtaza, MA (2015). "Xylitol: a review on bioproduction, application, health benefits, and related safety issues". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 55 (11): 1514–28. doi:10.1080/10408398.2012.702288. PMID 24915309.

- Wrolstad, Ronald E. (2012). Food Carbohydrate Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 176. ISBN 9780813826653. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- Jain, H; Mulay, S (March 2014). "A review on different modes and methods for yielding a pentose sugar: xylitol". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 65 (2): 135–43. doi:10.3109/09637486.2013.845651. PMID 24160912.

- Felipe Hernández-Pérez, Andrés; de Arruda, Priscila Vaz; Sene, Luciane; da Silva, Silvio Silvério; Kumar Chandel, Anuj; de Almeida Felipe, Maria das Graças (2019-07-16). "Xylitol bioproduction: state-of-the-art, industrial paradigm shift, and opportunities for integrated biorefineries". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 39 (7): 924–943. doi:10.1080/07388551.2019.1640658. ISSN 0738-8551. PMID 31311338.

- "Xylitol". Drugs.com. 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Xylitol; from Part 172, Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption, Special Dietary and Nutritional Additives; Sec. 172.395". Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. United States Food and Drug Administration. 2012-04-01.

- "Xylitol". Diabetes.co.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Burgos, Karen; Subramaniam, Persis; Arthur, Jennifer (21 November 2016). "Reformulation guide for small to medium sized companies" (PDF). Leatherhead Food Research via The Food and Drink Federation.

- "Is xylitol good for your teeth?". NHS Eat well. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "Xylitol chewing gum/pastilles and reduction of the risk of tooth decay – Scientific substantiation of a health claim related to xylitol chewing gum/pastilles and reduction the risk of tooth decay". EFSA Journal. 6 (11): 852. November 2008. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2008.852.

- "Policy on the use of xylitol in caries prevention" (PDF). Reference Manual. 33 (6): 42–44. 2010. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- Mickenautsch, Steffen; Yengopal, Veerasamy (2012). "Effect of xylitol versus sorbitol: A quantitative systematic review of clinical trials". International Dental Journal. 62 (4): 175–188. doi:10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00113.x. PMID 23016999.

- Mickenautsch, Steffen; Yengopal, Veerasamy (2012). "Anticariogenic effect of xylitol versus fluoride – a quantitative systematic review of clinical trials". International Dental Journal. 62 (1): 6–20. doi:10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00086.x. PMID 22251032.

- Söderling, E (April 2009). "Controversies around Xylitol". European Journal of Dentistry. 3 (2): 81–2. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1697411. PMC 2676064. PMID 19421385.

- "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to the sugar replacers xylitol, sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, lactitol, isomalt, erythritol, D-tagatose, isomaltulose, sucralose and polydextrose and maintenance of tooth mineralisation by decreasing tooth demineralisation, and reduction of post-prandial glycaemic responses". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2076. April 2011. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2076.

- "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to sugar-free chewing gum sweetened with xylitol and plaque acid neutralisation (ID 485), maintenance of tooth mineralisation (ID 486, 562, 1181), reduction of dental plaque (ID 485, 3085)". EFSA Journal. 9 (6): 2266. June 2011. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2266.

- Azarpazhooh, A; Lawrence, HP; Shah, PS (3 August 2016). "Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD007095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007095.pub3. PMID 27486835.

- Marom, Tal; Marchisio, Paola; Tamir, Sharon Ovnat; Torretta, Sara; Gavriel, Haim; Esposito, Susanna (2016-02-12). "Complementary and alternative medicine treatment options for otitis media". Medicine. 95 (6): e2695. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002695. ISSN 0025-7974. PMC 4753897. PMID 26871802.

- Salli, Krista; Lehtinen, Markus J.; Tiihonen, Kirsti; Ouwehand, Arthur C. (2019-08-06). "Xylitol's Health Benefits beyond Dental Health: A Comprehensive Review". Nutrients. 11 (8): 1813. doi:10.3390/nu11081813. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6723878. PMID 31390800.

- Tiefenbacher, Karl F. (2017). "Technology of Main Ingredients—Sweeteners and Lipids". Wafer and Waffle. Elsevier. pp. 123–225. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-809438-9.00003-x. ISBN 978-0-12-809438-9.

- Foster-Powell, K; Holt, SH; Brand-Miller, JC (July 2002). "International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (1): 5–56. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.1.5. PMID 12081815.

- Mäkinen, Kauko (2016-10-20). "Gastrointestinal Disturbances Associated with the Consumption of Sugar Alcohols with Special Consideration of Xylitol: Scientific Review and Instructions for Dentists and Other Health-Care Professionals". International Journal of Dentistry. 2016: 5967907. doi:10.1155/2016/5967907. PMC 5093271. PMID 27840639.

- "Sugar Alcohols" (PDF). Canadian Diabetes Association. 2005-05-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- Janket S, Benwait J, Isaac P, Ackerson LK, Meurman JH (2019). "Oral and systemic effects of xylitol consumption". Caries Research. 53 (5): 491–501. doi:10.1159/000499194. hdl:10138/305074. PMID 31060040.

- Schmid RD, Hovda LR (2016). "Acute hepatic failure in a dog after xylitol ingestion". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 12 (2): 201–205. doi:10.1007/s13181-015-0531-7. PMC 4880608. PMID 26691320.

- Jerzsele A, et al. (2018). "Effects of p.o. administered xylitol in cats". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 41 (3): 409–414. doi:10.1111/jvp.12479. PMID 29430681.

- "Chapter 3: Calculation Of The Energy Content Of Foods – Energy Conversion Factors". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Livesey, G. (2003). "Health potential of polyols as sugar replacers, with emphasis on low glycaemic properties". Nutrition Research Reviews. 16 (2): 163–191. doi:10.1079/NRR200371. ISSN 1475-2700. PMID 19087388.

- Wölnerhanssen BK, Meyer-Gerspach AC, Beglinger C, Islam MS (June 2019). "Metabolic effects of the natural sweeteners xylitol and erythritol: A comprehensive review". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition: 1–13. doi:10.1080/10408398.2019.1623757. PMID 31204494.

- Hicks, Jesse (Spring 2010). "The Pursuit of Sweet". Science History Institute.

External links