Dukeries Junction railway station

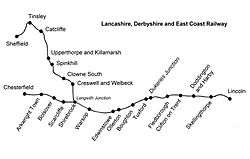

Dukeries Junction, originally Tuxford Exchange,[4] was a railway station near Tuxford, Nottinghamshire, England. The station opened in 1897 and closed in 1950. It was located at the bridge where the Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway crossed over the East Coast Main Line (ECML), with sets of platforms on both lines. The high-level location is now part of the High Marnham Test Track.

| Dukeries Junction | |

|---|---|

_station_site_geograph-3422104-by-Ben-Brooksbank.jpg) Site of the station's high level platforms in 1992 | |

| Location | |

| Place | Tuxford |

| Area | Bassetlaw, Nottinghamshire |

| Coordinates | 53.2256°N 0.8774°W |

| Grid reference | SK 750 704 |

| Operations | |

| Original company |

|

| Pre-grouping |

|

| Post-grouping | London and North Eastern Railway British Railways |

| Platforms | 4; 2 at ground level, 2 overhead[1] |

| History | |

| 1 June 1897 | Opened as Tuxford Exchange, later renamed Dukeries Junction[2] |

| 6 March 1950 | Closed[3] |

| Disused railway stations in the United Kingdom | |

| Closed railway stations in Britain A B C D–F G H–J K–L M–O P–R S T–V W–Z | |

| Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Great Northern Railway Main Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Variations

There were three Tuxford stations, though none was very near the centre of the village. They were:

- Dukeries Junction, at the bridge carrying the Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway over the Great Northern Railway main line,

- Tuxford Central, one mile west of the bridge over the ECML, and

- Tuxford North, half a mile north of the bridge over the ECML.[5]

Context

The station was jointly opened by the LD&ECR and GNR on 1 June 1897.[6] It was originally called "Tuxford Exchange", being situated where the LD&ECR's main line from Chesterfield Market Place to Lincoln (later Lincoln Central) crossed over the GNR's main line from Kings Cross to Doncaster. It was soon renamed "Dukeries Junction". The station was closed by British Railways in March 1950.

Dukeries Junction was, in modern parlance, a two-level interchange. It was never intended to serve Tuxford as such, being situated throughout its life surrounded on one quarter by railway sidings and an engine shed and on the other three quarters by fields, with no road access.[7] The LD&ECR hoped to attract tourist traffic to the North Nottinghamshire area, which they promoted as "The Dukeries", though this traffic never materialised. Years after it closed, Centre Parcs became a success in the Dukeries. The station's principal use over the years was by railway workers at the workshop and engine shed described below.

The station had two opposing platforms on the GNR's lower level tracks[8][9][10] and wooden buildings on a wooden, island platform with two faces on the LD&ECR's tracks immediately above.[11][12][13][14][15][16] The two levels were connected by stairs. The only other station on the LD&ECR with an island platform was Scarcliffe. Of the LD&ECR stations only Tuxford Central and Dukeries Junction were recorded as being electrically lit, the others being lit by gas or oil.[17] A down loop ran outside the more westerly low level platform and a refuge siding lay behind the southbound platform. The footpath to the station passed between the main line and this siding.[18]

On 16 November 1896, a substantial, 60 chains (1.2 km)[19] double-track, West-North connection ("chord") was opened joining the LD&ECR and the GNR, effectively creating a triangle,[20][21][22] with a station near each point, as shown on the 1947 map linked below. The chord carried goods, but no regular passenger traffic, though it came to life at summer weekends up to 1964 with holiday trains and excursions from Nottinghamshire to the Yorkshire Coast which passed through without stopping. It played a part in a minor railway "last", in that the final timetabled steam train south along the ECML from Retford was not a LNER Gresley Classes A1 and A3|Gresley A3 to Kings Cross, but Stanier Black 5 No. 45444 running to Nottingham Victoria via Tuxford's West to North curve in September 1964.[23] The chord was in plain view of Dukeries Junction station but did not pass through it.

An embankment was built for a proposed west to south curve, but tracks were never laid.[24][25]

Former Services

There never was a Sunday service at Dukeries Junction.

In 1922, three trains per day left Dukeries Junction high level eastbound for Lincoln, with a market day extra on Fridays; while three trains per day left Dukeries Junction high level westbound for Chesterfield Market Place (with the Friday extra terminating at Langwith Junction—later renamed Shirebrook North).[26]

Two trains per day left Dukeries Junction low level northbound for Tuxford North and Retford, with a third calling to set down only, except on Fridays when it both picked up and set down. Three trains per day left Dukeries Junction low level southbound for Crow Park and Newark, with a third calling to set down only, except on Fridays when it both picked up and set down.[27]

There were eight possible traffic flows:

- Northbound, change platform, proceed Eastwards (e.g. London to Fledborough)

- Westbound, change platform, proceed Southwards (e.g. return from Fledborough to London)

- Southbound, change platform, proceed Eastwards (e.g. York to Fledborough)

- Westbound, change platform, proceed Northwards (e.g. return from Fledborough to York)

The traffic potential of these four flows was very limited, especially as there were far easier ways to get to and from Lincoln from both the North and the South. The companies clearly gave up on it, with an average waiting time of 116 minutes and a best case of 87 minutes, discounting the one train which gave a waiting time of three minutes, far too short to be practical where the connection was unadvertised so no train need be held if a service was late.

- Northbound, change platform, proceed Westwards (e.g. London to Edwinstowe )

- Eastbound, change platform, proceed Southwards (e.g. return from Edwinstowe to London)

- Southbound, change platform, proceed Westwards (e.g. York to Edwinstowe)

- Eastbound, change platform, proceed Northwards (e.g. return from Edwinstowe to York)

Given that the LD&ECR proclaimed itself as the Dukeries Route these latter four flows would be the target market, e.g. people visiting the area for a holiday or enabling the comfortably off of the area to travel to destinations such as London. Even so, the average waiting time was 56 minutes, skewed towards the last pair, where the average wait was 48 minutes. Dukeries Junction was in the middle of nowhere without refreshment facilities or even road access, such waits may not have been an inviting prospect.

After Closure

Unusually for those days, the high level buildings were demolished not long after closure. The low level lines remain heavily used, though they were progressively rationalised as wagonload freight traffic declined.

Trains continued to pass through the high level station site,[28] with summer excursions via Lincoln continuing until 1964, but the picture was of a progressive decline. The chord was closed on 3 February 1969.[29] The run-down was abruptly accelerated in 1980 when a derailment west of Fledborough Viaduct led to the immediate closure of the line as a through route.

From 1980 the only traffic—apart from occasional enthusiasts' specials—was coal to High Marnham Power Station. When the power station closed in 2003 the track through the high level station site became redundant.

Tuxford Works and Engine Shed

East of the triangle of lines described above was Tuxford Locomotive Works, and within the triangle was Tuxford Engine Shed. Both were plainly visible from Dukeries Junction station.[30]

The locomotive works, known locally as "The Plant",[31] was small but capable of performing most engineering functions, other than locomotive building. It could, for example, replace locomotive boilers and fireboxes. It employed 130 men.[32] The LNER closed it as a locomotive works in 1927, but it continued as a carriage and predominantly wagon works for many years thereafter. The buildings were more or less intact in 1972, but by 1977 had all been razed to the ground, except the main erecting halls, which are still used today, albeit not for railway purposes.[32][33][34]

The engine shed[35] was originally expected to be the line's principal depot, however, it was soon realised that the main centre of activity would be at Langwith Junction, nevertheless, it survived 31 January 1959. The shed was equipped with a water softening plant, but no turntable. Coaling facilities were crude to the end. The shed was the final home of the original LD&ECR Class D 0-6-4T "Big Tanks"[32][36][31]

Upon closure, locomotives and jobs were transferred to Langwith Junction, so a daily Dido train was provided for the staff concerned.[37][38]

Modern Times

The ex-GNR low level lines are now electrified and known as the East Coast Main Line, they carry heavy express traffic at 100 mph and more. When the line was electrified the tracks were slewed to increase speeds and all trace of the low level station was erased.

The ex-LD&ECR high level line through the site of Dukeries Junction was reopened to non-passenger traffic in August 2009 as the High Marnham Test Track. The line is used by Network Rail to test new engineering trains and on-track plant.

The new test line runs from Thoresby Colliery Junction to the site of the partially demolished High Marnham Power Station, and passes the former station sites of Ollerton, Boughton (Nottinghamshire), Tuxford Central and Dukeries Junction.[39]

| Preceding station | Disused railways | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuxford Central Line and station closed |

Great Central Railway High Level Platforms, LD&ECR |

Fledborough Line and station closed | ||

| Tuxford North Line open, station closed |

Great Northern Railway Low Level Platforms |

Crow Park Line open, station closed |

References

- Cowlishaw 2006, p. 62.

- Little 2002b, p. 2.

- Butt 1995, p. 84.

- Taylor 2018, p. 731.

- All Tuxford Stations on an OS map npe Maps

- Ludlam 2013, p. 140.

- Stewart-Smith 2016b, p. 22.

- Little 2002b, p. 3.

- Lund 1999, p. 24.

- Stewart-Smith 2016a, p. 31.

- Ludlam 2013, p. 137.

- Stewart-Smith 2016a, pp. 31-2.

- Dukeries Junction Picture the Past

- Dukeries Junction Signalboxes

- Anderson 2013, p. 341.

- Booth 2013, p. 47.

- Dow 1965, p. 164.

- Taylor 2018, pp. 728-731.

- Dow 1965, p. 159.

- Kaye 1988, p. 70.

- Greening 1982, p. 63.

- Stewart-Smith 2016a, pp. 30 & 32.

- Marsden 2004, 34 mins from start.

- Cupit & Taylor 1984, p. 21.

- The Railway Magazine 1944, p. 63.

- Bradshaw 1985, p. 718.

- Bradshaw 1985, p. 332.

- Walker 1991, Inside front cover.

- Ludlam 2013, p. 144.

- Stewart-Smith 2016b, p. 23.

- Stewart-Smith 2016a, p. 33.

- Little 2002b, p. 7.

- Dow 1965, p. 163.

- Stewart-Smith 2016a, p. 35.

- Little 2002b, pp. 4, 6 & 8.

- Ludlam 2013, pp. 137 & 142.

- Little 2002a, p. 11.

- Stewart-Smith 2016b, p. 24.

- "Preparing for the Future: Network Rail Opens Vehicle Development Centre". Press Releases (Press release). Network Rail. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

Sources

- Anderson, Paul (June 2013). Hawkins, Chris (ed.). "Out and About with Anderson". Railway Bylines. Clophill: Irwell Press Ltd. 18 (7). ISSN 1360-2098.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Booth, Chris (2013). The Lancashire, Derbyshire and East Coast Railway A pictorial view of the "Dukeries Route" and branches. Two: Langwith Junction to Lincoln, the Mansfield Railway and Mid Nott's Joint Line. Blurb. ISBN 978-1-78155-660-3. 06884827.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradshaw, George (1985) [July 1922]. Bradshaw's General Railway and Steam Navigation guide for Great Britain and Ireland: A reprint of the July 1922 issue. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8708-5. OCLC 12500436.

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Cowlishaw, John (2006). British Railways in and Around the Midlands 1953-57. Nottingham: Book Law Publications. ISBN 978-1-901945-47-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cupit, J.; Taylor, W. (1984) [1966]. The Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway. Oakwood Library of Railway History (2nd ed.). Headington: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-302-2. OL19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dow, George (1965). Great Central, Volume Three: Fay Sets the Pace, 1900–1922. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0263-0. OCLC 500447049.

- Greening, David (1982). Steam in the East Midlands. Kings Lynn: Becknell Books. ISBN 978-0-907087-09-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaye, A.R. (1988). North Midland and Peak District Railways in the Steam Age, Volume 2. Chesterfield: Lowlander Publications. ISBN 978-0-946930-09-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Little, Lawson (Summer 2002a). Bell, Brian (ed.). "Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway A personal View 1945-74 (Part I)". Forward. Holton-le-Clay: Brian Bell for the Great Central Railway Society. 132. ISSN 0141-4488.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Little, Lawson (Winter 2002b). Bell, Brian (ed.). "Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway (Part III) Brief History of Tuxford". Forward. Holton-le-Clay: Brian Bell for the Great Central Railway Society. 134. ISSN 0141-4488.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ludlam, A.J. (March 2013). Kennedy, Rex (ed.). "The Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway". Steam Days. Bournemouth: Redgauntlet 1993 Publications. 283. ISSN 0269-0020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lund, Brian (1999) [1991]. Nottinghamshire Railway Stations on old picture postcards. Keyworth: Reflections of a Bygone Age. ISBN 978-0-946245-36-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marsden, Michael (2004) [1959-65]. Doncaster. Birkenshaw, West Yorkshire: Marsden Rail. DVD, Vol 11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- British Railways Atlas 1947: The Last Days of the Big Four. Hersham: Ian Allan Publishing. April 2011 [1948]. ISBN 978-0-7110-3643-7. 1104/A2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart-Smith, Robin (October 2016a). Milner, Chris (ed.). "Tuxford: The growth and decline of a railway centre, Part 1". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 162 no. 1387. Horncastle, Lincolnshire: Mortons Media Group Ltd. ISSN 0033-8923.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart-Smith, Robin (November 2016b). Milner, Chris (ed.). "Tuxford: The growth and decline of a railway centre, Part 2". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 162 no. 1388. Horncastle, Lincolnshire: Mortons Media Group Ltd. ISSN 0033-8923.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Bill (December 2018). Blakemore, Michael (ed.). "Dukeries Junction". Back Track. Vol. 32 no. 12. Easingwold: Pendragon Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Colin (1991). Eastern Region Steam Twilight, Part 2, North of Grantham. Llangollen: Pendyke Publications. ISBN 978-0-904318-14-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Lancashire, Derbyshire and E. Coast Ry". The Why and the Wherefore. The Railway Magazine. Vol. 90 no. 549. London: Tothill Press Limited. January–February 1944. pp. 63–64. ISSN 0033-8923.

External links

- All Tuxford Stations on an old O.S. Map npe Maps

- The station on OS maps with overlays National Library of Scotland

- Tuxford Stations and linesRail Map Online

- The station on line HIM2 Railway Codes

- The station on line ECM1 Railway Codes

- Tuxford Stations and former signalboxesSignalboxes

- Tuxford area railways, including Dukeries Jct Old Tuxford

- Tuxford area railways, including Dukeries Jct The Goods yard

- Tuxford Jct, with Dukeries Jct on the horizon RM Web

- Tuxford Jct, with Dukeries Jct site on the horizon Rail Online

- Dukeries Jct from the north Picture the Past

- GN main line train seen from Dukeries Jct high level flickr

- Train arriving at Dukeries Jct high level Chasewater Stuff

- LDECR poster Pinterest