Direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest; in contrast to those actions that appeal to others (e.g. authorities); by, for example, revealing an existing problem, using physical violence, highlighting an alternative, or demonstrating a possible solution.

Both direct action and actions appealing to others can include nonviolent and violent activities which target persons, groups, or property deemed offensive to the action participants. Examples of nonviolent direct action (also known as nonviolence, nonviolent resistance, or civil resistance) can include (obstructing) sit-ins, strikes, workplace occupations, street blockades or hacktivism, while violent direct action may include political violence or assaults. Tactics such as sabotage and property destruction are legally considered violent.

By contrast, electoral politics, diplomacy, negotiation, protests and arbitration are not usually described as direct action, as they are electorally mediated. Non-violent actions are sometimes a form of civil disobedience, and may involve a degree of intentional law-breaking where persons place themselves in arrestable situations in order to make a political statement but other actions (such as strikes) may not violate criminal law.

The aim of direct action is to either obstruct another political agent or political organization from performing some practice to which the activists object, or to solve perceived problems which traditional societal institutions (governments, religious organizations or established trade unions) are not addressing to the satisfaction of the direct action participants.

Non-violent direct action has historically been an assertive regular feature of the tactics employed by social movements, including Mahatma Gandhi's Indian Independence Movement and the Civil Rights Movement.

History

Direct action tactics have been around for as long as conflicts have existed but it is not known when the term first appeared. The radical union the Industrial Workers of the World first mentioned the term "direct action" in a publication in reference to a Chicago strike conducted in 1910.[1] Other noted historical practitioners of direct action include the American Civil Rights Movement, the Global Justice Movement, the Suffragettes, LGBT and other human rights movements (I.e, ACT UP); revolutionary Che Guevara, and certain environmental advocacy groups.

American anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre wrote an essay called "Direct Action" in 1912 which is widely cited today. In this essay, de Cleyre points to historical examples such as the Boston Tea Party and the American anti-slavery movement, noting that "direct action has always been used, and has the historical sanction of the very people now reprobating it."[2]

In his 1920 book, Direct Action, William Mellor placed direct action firmly in the struggle between worker and employer for control "over the economic life of society." Mellor defined direct action "as the use of some form of economic power for securing of ends desired by those who possess that power." Mellor considered direct action a tool of both owners and workers and for this reason, he included within his definition lockouts and cartels, as well as strikes and sabotage. However, by this time the US anarchist and feminist Voltairine de Cleyre had already given a strong defense of direct action, linking it with struggles for civil rights:

...the Salvation Army, which was started by a gentleman named William Booth was vigorously practising direct action in the maintenance of the freedom of its members to speak, assemble, and pray. Over and over they were arrested, fined, and imprisoned ... till they finally compelled their persecutors to let them alone.

— de Cleyre, undated

Martin Luther King felt that the goal of nonviolent direct action was to "create such a crisis and foster such a tension" as to demand a response.[3] The rhetoric of Martin Luther King, James Bevel, and Mohandas Gandhi promoted non-violent revolutionary direct action as a means to social change. Gandhi and Bevel had been strongly influenced by Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You, which is considered a classic text that ideologically promotes passive resistance.[4]

By the middle of the 20th century, the sphere of direct action had undoubtedly expanded, though the meaning of the term had perhaps contracted. Many campaigns for social change—such as those seeking suffrage, improved working conditions, civil rights, abortion rights or an end to abortion, an end to gentrification, and environmental protection—claim to employ at least some types of violent or nonviolent direct action.

Some sections of the anti-nuclear movement used direct action, particularly during the 1980s. Groups opposing the introduction of cruise missiles into the United Kingdom employed tactics such as breaking into and occupying United States air bases, and blocking roads to prevent the movement of military convoys and disrupt military projects. In the US, mass protests opposed nuclear energy, weapons, and military intervention throughout the decade, resulting in thousands of arrests. Many groups also set up semi-permanent "peace camps" outside air bases such as Molesworth and Greenham Common, and at the Nevada Test Site.

Environmental movement organizations such as Greenpeace have used direct action to pressure governments and companies to change environmental policies for years. On April 28, 2009, Greenpeace activists, including Phil Radford, scaled a crane across the street from the Department of State, calling on world leaders to address climate change.[5] Soon thereafter, Greenpeace activists dropped a banner off of Mt. Rushmore, placing President Obama's face next to other historic presidents, which read "History Honors Leaders; Stop Global Warming".[6]

In 2009, hundreds blocked the gates of the coal fired power plant that powers the US Congress building, following the Power Shift conference in Washington, D.C. In attendance at the Capitol Climate Action were Bill McKibben, Terry Tempest Williams, Phil Radford, Wendell Berry, Robert Kennedy Junior, Judy Bonds and many more prominent figures of the climate justice movement were in attendance.

Anti-abortion groups in the United States, particularly Operation Rescue, often used non-violent sit-ins at the entrances of abortion clinics as a form of direct action in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Anti-globalization activists made headlines around the world in 1999, when they forced the Seattle WTO Ministerial Conference of 1999 to end early with direct action tactics. The goal that they had, shutting down the meetings, was directly accomplished by placing their bodies and other debris between the WTO delegates and the building they were meant to meet in. Activists also engaged in property destruction as a direct way of stating their opposition to corporate culture—this can be viewed as a direct action if the goal was to shut down those stores for a period of time, or an indirect action if the goal was influencing corporate policy.

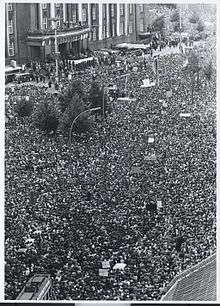

One of the largest direct actions in recent years took place in San Francisco the day after the Iraq War began in 2003. Twenty-thousand people occupied the streets and over 2,000 people were arrested in affinity group actions throughout downtown San Francisco, home to military-related corporations such as Bechtel. (See March 20, 2003 anti-war protest).

Direct action has also been used on a smaller scale. Refugee Salim Rambo was saved from being deported from the UK back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo when one person stood up on his flight and refused to sit down. After a two-hour delay the man was arrested, but the pilot refused to fly with Rambo on board. Salim Rambo was ultimately released from state custody and remains free today.

In the 1980s, a California direct action protest group called Livermore Action Group called its newspaper Direct Action. The paper ran for 25 issues, and covered hundreds of nonviolent actions around the world. The book Direct Action: An Historical Novel took its name from this paper, and records dozens of actions in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Human rights activists have used direct action in the ongoing campaign to close the School of the Americas, renamed in 2001 the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. As a result, 245 SOA Watch human rights defenders have collectively spent almost 100 years in prison. More than 50 people have served probation sentences.

"Direct Action" has also served as the moniker of at least two groups: the French Action Directe as well as the Canadian group more popularly known as the Squamish Five. Direct Action is also the name of the magazine of the Australian Wobblies. The UK's Solidarity Federation currently publishes a magazine called Direct Action.

Until 1990, Australia's Socialist Workers Party published a party paper also named "Direct Action", in honour of the Wobblies' history. One of the group's descendants, the Revolutionary Socialist Party, has again started a publication of this name.[7]

Food Not Bombs is often described as direct action because individuals involved directly act to solve a social problem; people are hungry and yet there is food available. Food Not Bombs is inherently dedicated to non-violence.

A museum that chronicles the history of direct action and grassroots activism in the Lower East Side of New York City, the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space, opened in 2012.

Nonviolent

.jpg)

Principled nonviolence is a positive force in its own right and involves active concern for the well being of the opponent even while resisting the latter's actions. Mohandas Gandhi's teachings of Satyagraha (or truth force) have inspired many practitioners of nonviolent direct action. In his first book, Stride Toward Freedom, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. described the basics of nonviolence, saying that it

- 1. ... is a way of life for courageous people...,

- 2. ... seeks to win friendship and understanding...,

- 3. ... seeks to defeat injustice not people...,

- 4. ... holds that suffering can educate and transform...,

- 5. ... chooses love instead of hate...,

- 6. ... believes that the universe is on the side of justice.[8]

Applied strategically to his campaign for civil rights, Dr. King wrote in his Letter from Birmingham Jail that "Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks to so dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored."[3]

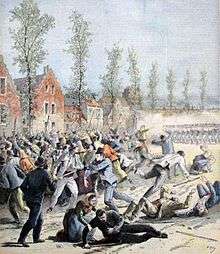

Violent

Violent direct action is any direct action which utilizes physical injurious force against persons or, controversially (see below), property.[2] Examples of violent direct action include: rioting, lynching, terrorism, political assassination, freeing political prisoners, interfering with police actions, armed insurrection, and arguably property destruction.

Ann Hansen, one of the Squamish 5, also known as Vancouver 5, a Canadian anarchist and self-professed urban guerrilla fighter, wrote in her book Direct Action that,

The essence of direct action ... is people fighting for themselves, rejecting those who claim to represent their true interests, whether they be revolutionaries or government officials. It is a far more subversive idea than civil disobedience because it is not meant to reform or influence state power but is meant to undermine it by showing it to be unnecessary and harmful. When people, themselves, resort to violence to protect their community from racist attacks or to protect their environment from ecological destruction, they are taking direct action.[9]:335

Controversy over destruction of property

One major debate is whether destruction of property should be included within the realm of violence or nonviolence. This debate can be illustrated by the response to groups like the Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front, which use property destruction and sabotage as direct action tactics. Although these types of actions are often prosecuted as violence, those groups justify their actions by claiming that violence is harm directed towards living things and not property. The issue of whether sabotage is a form of violence is difficult to resolve in purely philosophical terms, but the use of sabotage as a method can be contrasted with minor property damage that is a small but necessary part of a non-violent campaign method such as breaking locks and fences to gain entry to a site.[10] Some theorists and activists believe that a doctrine of diversity of tactics can resolve the controversy.[11][12]

US and international law include acts against property in the definition of violence and state that even in a time of war, "Destruction [of property] as an end in itself is a violation of international law".[13]:218

United Kingdom

The environmental direct action movement in the United Kingdom started in 1990 with the forming of the first UK Earth First! group. The movement rapidly grew from the 1992 Twyford Down protests, culminating in 1997.

There are now several organisations in the United Kingdom campaigning for action on climate change that use non-violent direct action, including Camp for Climate Action, Plane Stupid, Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion. This has resulted in environmental campaigners being labelled as extremists by the Ministry of Justice.[14]

See also

- Active citizenship

- Activism

- Anarchism

- Arms trafficking

- Citizen journalism

- Civil disobedience

- Civil resistance

- Counterfeiting

- Critical animal studies

- Direct democracy

- Direct Action Day

- Dual power

- General strike

- Hacktivism

- Improvised explosive device

- Improvised fighting vehicle

- Improvised vehicle armour

- Independent Media Center

- Insurrection

- List of anti-war organizations

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of peace activists

- Nonviolence

- Nonviolent resistance

- Off-the-grid energy or Solar energy

- Pirate radio or free radio

- Political radicalism

- Propaganda of the deed

- Property destruction

- Rebellion

- Revolution

- Sabotage or Ecotage

- Satyagraha

- Security culture

- Smuggling

- Squatting

- Tax resistance

- Tree sitting

- Tree spiking

- Some groups which employ or employed direct action

- ADAPT

- AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP)

- Anarchists Against the Wall (Israeli group)

- Animal Liberation Front

- Animal Liberation Press Office

- Anonymous (group)

- Antifa (United States)

- A Quaker Action Group

- BAMN

- Camp for Climate Action

- Campus Antiwar Network

- Code Pink

- Committee of 100 (United Kingdom)

- Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

- Connolly Youth Movement

- Cop Block

- Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg

- Cypherpunk

- Direct Action Committee

- Direct Action Everywhere

- Direct Action to Stop the War

- Earth First!

- Earth Liberation Front

- Euromaidan

- Extinction Rebellion

- Food Not Bombs[15]

- GetEQUAL

- Green Mountain Anarchist Collective

- Greenpeace

- Homes Not Jails

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Landless Workers' Movement

- Lesbian Avengers

- Movement for a New Society

- MindFreedom International

- National Bolshevik Party

- National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam

- No Border network

- Occupy Wall Street

- Operation Save America

- PETA

- Plane Stupid

- Reclaim the Streets

- Rising Tide North America

- School of the Americas Watch (SOA Watch)

- School strike for climate

- Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

- Sons of Liberty

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

- Squamish Five

- Students for a Democratic Society

- Take Back the Land

- Trident Ploughshares

- UkUncut

- Vetëvendosje! - Movement for Self-determination in Kosova

- War Resisters' International

- WOMBLES

- Yellow vests movement

- Zero Hour

References

- The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years, 1905-1975, Fred W. Thompson and Patrick Murfin, 1976, page 46.

- de Cleyre, Voltairine (1912). – via Wikisource.

- King, Martin Luther, Jr. (16 April 1963). "Letter from Birmingham Jail".

- Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (2010). Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel. Exeter: Imprint Academic. p. 19

- "First Day on the Job!". Grist.org. 2009-04-28. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Greenpeace Scales Mt Rushmore – issues challenge to Obama". Christian Science Monitor. Grist.org. 2009-07-09. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- Percy, John (June 2008). "Direct Action – two earlier versions". Revolutionary Socialist Party. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- "The King Philosophy". thekingcenter.org. The King Center.

- Hansen, Ann. Direct Action: Memoirs of an Urban Guerrilla. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2001. ISBN 978-1902593487

- Dieter Rucht. Violence and New Social Movements. In: International Handbook of Violence Research, Volume I. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2003, p. 369-382.

- "Hallmarks of People’s Global Action (amended at the 3rd PGA conference at Cochamamba, 2001)".

- Rowe, James K.; Carroll, Myles (2014-04-03). "Reform or Radicalism: Left Social Movements from the Battle of Seattle to Occupy Wall Street". New Political Science. 36 (2): 149–171. doi:10.1080/07393148.2014.894683. ISSN 0739-3148.

- Orakhelashvili, Alexander. The Interpretation of Acts and Rules in Public International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Taylor, Matthew (26 January 2010). "Ministry of Justice lists eco-activists alongside terrorists". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS". Food Not Bombs. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

Further reading

- Hauser, Luke (2003) Direct Action: An Historical Novel. Available at www.directaction.org.

- Lunori, G. (1999) Direct Action. Available at sniggle.net.

- Kauffman, L.A. (2017) "Direct Action: Protest and the Reinvention of American Radicalism". New York, Verso, 2017. ISBN 9781784784096

- Sparrow, R. (undated) Anarchist Politics and Direct Action. Available at Spunk Online Anarchist Library.

- A Communiqué on Tactics and Organization to the Black Bloc, from within the Black Bloc, by The Green Mountain Anarchist Collective (NEFAC-VT) & Columbus Anti-Racist Action, Black Clover Press, 2001.

- The Black Bloc Papers: An Anthology of Primary Texts From The North American Anarchist Black Bloc 1988-2005, by Xavier Massot & David Van Deusen of the Green Mountain Anarchist Collective (NEFAC-VT), Breaking Glass Press, 2010.

- Hansen, Ann. Direct Action: Memoirs of an Urban Guerrilla. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2001. ISBN 978-1902593487

- Van Deusen On North American Black Blocs 1996-2001, by David Van Deusen, The Anarchist Library, 2017.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Direct action |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Direct action. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- DA! (Direct Action) Gallery. Direct Action in Londons Art scene.

- Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching

- Direct Action News from Germany

- ACTivist Magazine

- Civil Disobedience Manual from ACT-UP/NY

- ReclaimingQuarterly.org features photo-coverage of contemporary nonviolent direct actions

- DirectAction.org offers online organizing resources

- Greenpeace encourages its activists to use Non-Violent Direct Action

- The Citizen's Handbook

- Ruckus

- The Boston Direct Action Project

- IWW Organizing Department

- libcom.org/organise - organising direct action at work, in the community or anywhere else tips and guidelines

- War Resisters' International

- The Scouring of the Shire: Fairies, Trolls and Pixies in Eco-Protest Culture by Andy Letcher (2001)

- Video clips of some direct action

- A bi-lingual database on all known direct action news in Greece since September 2007

- www.direct-action.de.vu German Direct-Action-Site

- www.directaction.org/youtube Video: A Brief History of Direct Action - by Luke Hauser, GroundWork