Dundalk

Dundalk (/dʌnˈdɔːk/ dun-DAWK; Irish: Dún Dealgan [ˌd̪ˠuːnˠ ˈdʲalˠɡənˠ], meaning "Dalgan's fort") is the county town of County Louth, Ireland. It is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is near the border with Northern Ireland (8 km from the town centre), 82 km north of Dublin and 83 km south of Belfast. In the 2016 census, the population was 39,004.

Dundalk Dún Dealgan | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Clockwise from top: Castle Roche, Clarke Station, St. Patrick's Pro-Cathedral, The Marshes Shopping Centre, Market Square, Dundalk Institute of Technology | |

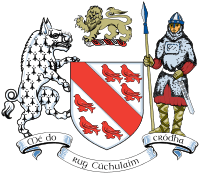

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): | |

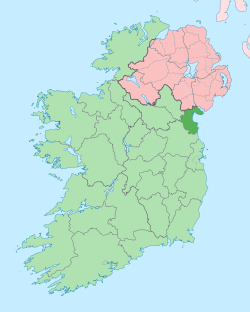

Dundalk Location in Ireland  Dundalk Dundalk (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 54.009°N 6.4049°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Louth |

| Dáil Éireann | Louth |

| EU Parliament | Midlands–North-West |

| Inhabited | 3500 BC[1][2][3] |

| Charter | 1189 |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 25.19 km2 (9.73 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 354.04 km2 (136.70 sq mi) |

| Population (Census 2016) | |

| • Rank | 8th |

| • Urban | 39,004[5] |

| • Metro | 55,806[6] |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing key | A91 |

| Telephone area code | +353(0)42 |

| Irish Grid Reference | J048074 |

| Website | www |

Having been inhabited since the Neolithic period, the town was established as a Norman stronghold in the 12th century following the Norman invasion of Ireland, and became the northernmost outpost of The Pale in the Late Middle Ages. It has associations with the mythical warrior hero Cú Chulainn and the motto on the town's coat of arms is Mé do rug Cú Chulainn cróga (Irish) "I gave birth to brave Cú Chulainn". The town came to be nicknamed the "Gap of the North" where the northernmost point of the province of Leinster meets the province of Ulster (although the actual 'gap' is the Moyry Pass at the border). The modern street layout dates from the early 18th century and largely owes its form to Lord Limerick (James Hamilton, later 1st Earl of Clanbrassil).

Dundalk developed brewing, distilling, tobacco, textile, shoe manufacturing, and engineering industries and became an important centre of trade both as a hub on the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) network and with its maritime link to Liverpool from the Port of Dundalk. But the town later suffered from high unemployment after many of these industries closed or scaled back operations—particularly in the aftermath of the Partition of Ireland in 1921 and the accession of Ireland to the European Economic Community in 1973. Following the Celtic Tiger period of the late 20th century, new industries have been established including pharmaceutical, electronic, financial services and specialist foods.

The town has one Third-level education institute—Dundalk Institute of Technology; and one museum—the County Museum Dundalk. Sporting clubs include Dundalk F.C. (who play at Oriel Park), Dundalk R.F.C., Dundalk Golf Club and a number of Gaelic football clubs. Dundalk Stadium is a horse and greyhound racing venue and is Ireland's only all-weather horse racing track.

History

Pre-Norman era (before 12th Century)

Following the end of the last Ice Age, it is believed that the Dundalk area was first inhabited circa 3700 BC, during the Neolithic period.[7] Visible evidence of this early presence can still be seen in the form of the Proleek Dolmen, the eroded remains of a portal tomb in the Ballymascanlon area, north of Dundalk, which dates to around 3000 BC. Evidence of early Christian settlements are to be found in the high concentration of souterrains in north Louth, which date from early Christian Ireland.[8]

The Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), an epic of early Irish literature, and the legends of Cú Chulainn are set in the first century AD, before the arrival of Christianity to Ireland. Clochafarmore (a menhir), the stone Cú Chulainn reputedly tied himself to before he died, is located to the east of the town.[9]

Saint Brigid is reputed to have been born in 451 AD in Faughart, a townland 6 km north of the centre of Dundalk, near the Moyry Pass.[10]

Most of what is recorded about the Dundalk area between the fifth century and the foundation of the town as a Norman stronghold in the 12th century comes from the Annals of the Four Masters and the Annals of Tigernach, written hundreds of years after the events they record. According to the annals, the plains of North Louth incorporating what is now Dundalk were known as Magh Muirthemne (the Plain of the Dark Sea). The area, bordered to the north east by Cuailgne (the Cooley peninsula) and to the south by the Ciannachta, was ruled by a Cruthin kingdom known as Conaille Muirtheimne in the early Christian period.[11]

The Annals of Ulster record that in 851, Danish Vikings (the Dubhgall) attempted to attack the Norwegian Viking (Fingall) settlement at Annagassan at the southern end of Dundalk Bay but were heavily defeated. The following year, Norwegian vikings based in Scotland were sent to attack the Danes in Carlingford Lough but their expedition was unsuccessful.[12] D'Alton's History of Dundalk recounts an apocryphal tale of the "Battle of Dundalk": Sitric, son of Turgesius, ruler of the Danes in Ireland, had offered Callaghan, the King of Munster, his sister in marriage. But it was a trick to take the king prisoner and he was captured and held hostage in Armagh. An army was raised in Munster and marched on Armagh to free the king, but he had been removed to Sitric's ship in Dundalk Bay. However, a fleet from Munster attacked the Danes in the bay from the south. The Munster admiral, Failbhe Fion, boarded Sitric's ship and freed the king, but was killed by Sitric who put his head on a pole. Failbhe Fion's second in command, Fingal, enraged, seized Citric by the neck and jumped into the sea where they both drowned. Two more Irish captains grabbed Sitric's two brothers and did the same, and the Danes subsequently surrendered.[13]

By the time of the Norman invasion of Ireland, Magh Muirthemne had been absorbed into the kingdom of Airgíalla (Oriel).[14]

Norman era (12th–14th centuries)

In 1169 the Normans arrived in Ireland and set about conquering large areas. By 1185 the Norman nobleman Bertram de Verdun had erected a manor house at Castletown Mount and in 1189 obtained the town's charter. de Verdun set about fortifying his lands and founded an Augustinian friary under the patronage of St Leonard. On his death in Jaffa in 1192, his lands at Dundalk passed to his son Thomas and then to his second son Nicholas. In 1236, Nicholas's daughter Roesia commissioned Castle Roche 10 km north-west of the present-day town, on a large rocky outcrop with a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. It was completed by her son, John, in the 1260s.[15]

Dundalk, effectively a frontier town, was routinely subject to raids from the clans of Ulster following its establishment. The Ulster Irish then sided with Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish king Robert the Bruce after he landed at Larne on 26 May 1315. As his army made its way south through Ulster, they destroyed the de Verdun fortress at Castle Roche and attacked Dundalk on 29 June. The town was almost totally destroyed and its population, both Anglo-Irish and Gaelic, massacred. After taking possession of the town, Bruce proclaimed himself King of Ireland. Following three more years of skirmishes and pillaging across the north-eastern part of the country, Bruce was killed and his army defeated at the Battle of Faughart by a force led by John de Birmingham, who was created the 1st Earl of Louth as a reward.[16]

English rule (14th–20th centuries)

The town was granted its first formal charter in the late 14th century under the reign of Richard II of England.[17] Later generations of de Verduns continued to own lands at Dundalk into the 14th century. Following the death of Theobald de Verdun, 2nd Baron Verdun in 1316 without a male heir, the family's fortunes started to wane and by 1380 a Richard de Verdun had been put in debtor's jail, while Batrtholomew de Verdun had much of the remaining de Verdun land confiscated by the crown after his part in the murder of the High Sheriff of Louth, John Dowdall, in 1402.[18]

Dundalk had been under Royalist (Ormondist) control for centuries, until 1647 when it became occupied by The Northern Parliamentary Army of Colonel George Monck.[19]

The modern town of Dundalk largely owes its form to Lord Limerick (James Hamilton, later 1st Earl of Clanbrassil) in the 17th century. He commissioned the construction of streets leading to the town centre; his ideas stemming from his visits to Continental Europe. In addition to the demolition of the old walls and castles, he had new roads laid out eastwards of the principal streets. The most important of these new roads connected a newly laid down Market Square, which still survives, with a linen and cambric factory at its eastern end, adjacent to what was once an army cavalry and artillery barracks (now Aiken Barracks).

In the 19th century, the town grew in importance and many industries were set up in the local area, including a large distillery. This development was helped considerably by the opening of railways, the expansion of the docks area or 'Quay' and the setting up of a board of commissioners to run the town.[20]

Since Independence (1921–present)

The partition of Ireland in May 1921 turned Dundalk into a border town and the Dublin–Belfast main line into an international railway. The Irish Free State opened customs and immigration facilities at Dundalk to check goods and passengers crossing the border by train. The Irish Civil War of 1922–23 saw a number of confrontations in Dundalk. The local Fourth Northern Division of the Irish Republican Army under Frank Aiken, who took over Dundalk barracks after the British left, tried to stay neutral but 300 of them were detained by the National Army in August 1922.[21] However, a raid on Dundalk Gaol freed Aiken and over 100 other anti-treaty prisoners;[22] two weeks later he retook Dundalk barracks and captured its garrison before freeing the remaining republican prisoners there. Aiken did not try to hold the town, however, and before withdrawing he called for a truce in a meeting in the centre of Dundalk. The 49 Infantry Battalion and 58 Infantry Battalion of the National Army were based in Dundalk along with No.8 armoured locomotive and two fully armoured cars of their Railway Protection Corps.

For several decades after the end of the Civil War, Dundalk continued to function as a market town, a regional centre, and a centre of administration and manufacturing. Its position close to the border and the IRA stronghold of South Armagh gave it considerable significance during the "Troubles" of Northern Ireland. Many people were sympathetic to the cause of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and Sinn Féin, and the town was home to numerous IRA operatives.[23] It was in this period that Dundalk earned the nickname 'El Paso', after the Texan border town of the same name on the border with Mexico.[2][24]

On 1 September 1973, the 27 Infantry Battalion of the Irish Army was established with its Headquarters in Dundalk barracks, renamed Aiken Barracks in 1986 in honour of Frank Aiken.

Dundalk suffered economically when Irish membership of the European Economic Community in the 1970s exposed local manufacturers to foreign competition that they were ill-equipped to cope with. The result was the closure of many local factories, resulting in the highest unemployment rate in Leinster, Ireland's richest province. High unemployment produced serious social problems in the town that were only alleviated by the advent of the Celtic Tiger investment boom at the start of the 21st century. Dundalk's economy has developed rapidly since 2000. Today many international companies have factories in Dundalk, from food processing to high-tech computer components. Harp Lager, a beer produced by Diageo, is brewed in the Great Northern Brewery, Dundalk.

In December 2000, Minister for Foreign Affairs Brian Cowen welcomed US president Bill Clinton to Dundalk to mark the conclusion of the Troubles and the success of the Northern Ireland peace process. Cowen said:

Dundalk is a meeting point between Dublin and Belfast, and has played a central role in the origin and evolution of the peace process. More than most towns in our country, Dundalk, as a border town, has appreciated the need for a lasting and just peace.[25]

The Earls of Roden[26] had property interests in Dundalk for over three centuries, and at an auction in July 2006 the 10th Earl sold his freehold of the town, including ground rents, mineral rights, manorial rights, the reversion of leases and the freehold of highways, common land, and the fair green. Included in the sale were many documents, such as a large 18th-century estate map. The buyer was undisclosed.[27]

Battles

- 248 – Battle fought at Faughart by Cormac Ulfada, High King of Ireland against Storno (Starno), king of Lochlin[28]

- 732 – Battle fought at Faughart by Hugh Allain, king of Ireland against the Ulaid[29]

- 851 – Battle at Dundalk Bay between the Fingall (Norwegian) and Dubhgall (Danish) Vikings takes place.[12]

- 877 – Gregory, King of Scotland took Dundalk en route to Dublin[30]

- 1178 – Battle fought on the outskirts of Dundalk between Normans under John de Courcy and local Irish under O'Hanlon. "The slaughter on both sides was great; few of the Irish, and fewer of the English, were left alive. Who got the best, there is no boast made."[31]

- 1318 – Battle of Dundalk (Battle of Faughart) fought on 14 October 1318 between a Hiberno-Norman force led by John de Bermingham, 1st Earl of Louth and Edmund Butler, Earl of Carrick and a Scots-Irish army commanded by Edward Bruce, brother of Robert Bruce, King of Scotland.[32][33]

- 1483 – Traghbally-of-Dundalk plundered and burned by Hugh Oge ally of Con O'Donnell[34]

- 1566 – O'Neill besieged the town with 4,000 footmen and 700 horsemen[35]

- 1688 – Brothers Malcolm and Archibald MacNeill, officers of William III land in Dundalk and defeat the Celtic MacScanlons in the Battle of Ballymascanlon[36]

- 1689 – Schomberg's Williamite Army camped to the north of the town record 6,000 deaths due to fever, scurvy, and ague[37]

- 1941 – On 24 July the town was bombed by the Luftwaffe with no casualties.

- 1971 – The Battle of Courtbane – on Sunday 29 August 1971 a British army patrol consisting of two armoured Ferret Scout cars crossed the Irish border into Co. Louth near the village of Courtbane close to Dundalk. When attempting to retreat back angry locals blocked their way and set one of the vehicles on fire. While this was happening an IRA unit arrived on the scene and after an exchange of gunfire a British soldier was killed and another one was wounded.[38]

- 1975 – The Dundalk Christmas Bombing – bombing carried out by the Ulster Volunteer Force on 19 December 1975 a car bomb killed 2 and injured 15[39][40]

Coat of arms

The Coat of Arms of Dundalk was officially granted by the Office of the Chief Herald at the National Library of Ireland in 1968, and is a replication of the Seal Matrix of the "New Town of Dundalk", which itself dates to the 14th Century.[41] A bend between six martlets forms the shield. The bend and martlets are derived from the family of Thomas de Furnivall,[42] who obtained a large part of the land and property of Dundalk and district in about 1309 by marriage to Joan de Verdon daughter of Theobald de Verdon (an Anglo-Norman family).[43] The ermine boar supporter is derived from the arms of the Ó hAnluain (O'Hanlon) family, Kings of Airthir. The origins of the foot soldier with his spear and sword is not known, neither is the lion on the crest, although the latter may be from the Mortimer family who held the Lordship of Louth in 1330. A Mortimer Castle stood in Park Street as late as the seventeenth century.

Prior to 1968, a simpler form of the seal – "three martlets proper on a blue field" – was used for the town's coat of arms, dating to when the town had been granted a charter in 1675.[44] It appears as the "Corporation Arms" in a town plan dated 1675.[45] This form of the Coat of Arms can be seen carved in stone on the Italianate Palazzo Town-hall, built between 1855 and 1865.[46] In 1930 the town council proposed to remove the "three black crows" from the seal of the town due to its English origins.[47] This coat of arms also became the crest of Dundalk Football Club in 1928, prior to the club severing its links with the Great Northern Railway (Ireland). The club's current crest retains three martlets on a red shield, as a nod to the town's granted Coat of Arms, but in reversed tinctures.

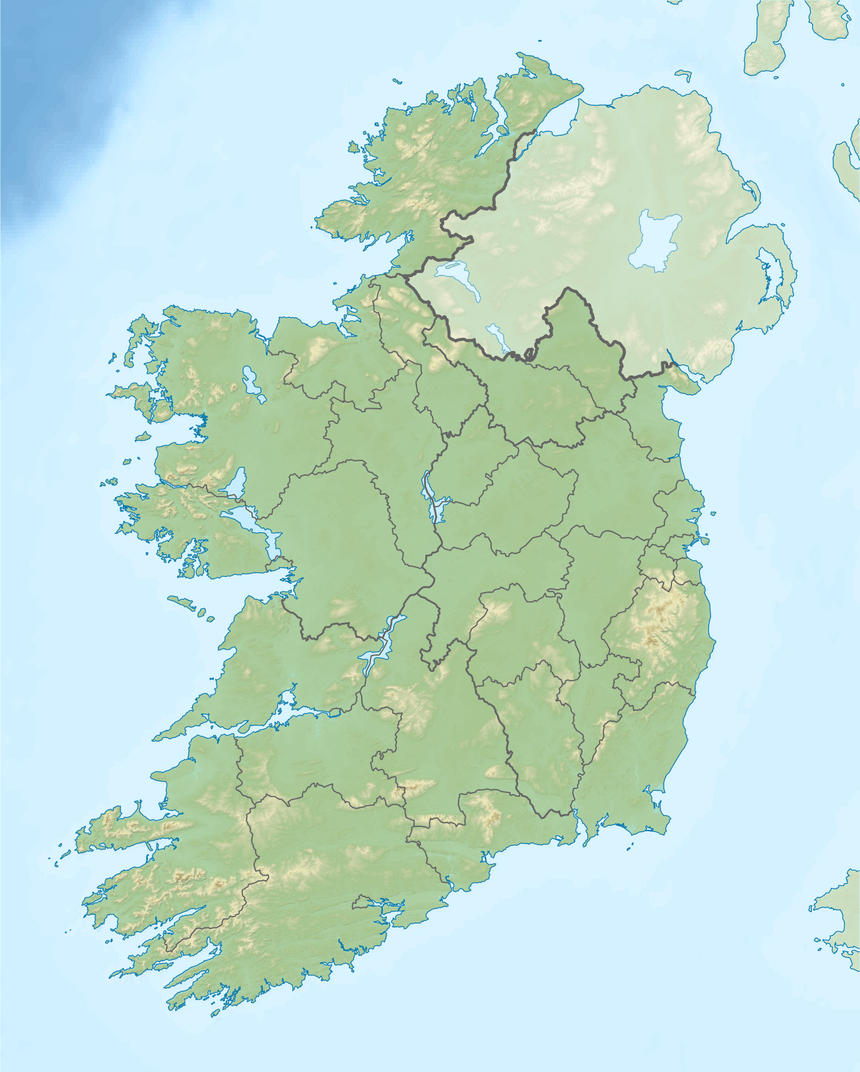

Geography

Landscape

Situated where the Castletown River flows into Dundalk Bay, the town is close to the border with Northern Ireland (3.5 km direct point-to-point aerial transit path border to border) and equidistant from Dublin and Belfast.

Climate

Similar to much of northwest Europe, Dundalk experiences an oceanic climate, sheltered by the Cooley and Mourne Mountains to the north, and undulating hills to the west and south, the town experiences cool winters, quite warm summers, and a lack of temperature extremes.

| Climate data for Dundalk, Leinster | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19 (66) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

8 (46) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.3 (48.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 85 (3.3) |

62 (2.4) |

66 (2.6) |

56 (2.2) |

62 (2.4) |

63 (2.5) |

66 (2.6) |

84 (3.3) |

84 (3.3) |

87 (3.4) |

81 (3.2) |

93 (3.7) |

889 (34.9) |

| Source: Dundalk climate | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 9,256 | — |

| 1831 | 10,078 | +8.9% |

| 1841 | 10,782 | +7.0% |

| 1851 | 9,842 | −8.7% |

| 1861 | 10,360 | +5.3% |

| 1871 | 11,327 | +9.3% |

| 1881 | 11,913 | +5.2% |

| 1891 | 12,449 | +4.5% |

| 1901 | 13,076 | +5.0% |

| 1911 | 13,128 | +0.4% |

| 1926 | 13,996 | +6.6% |

| 1936 | 14,684 | +4.9% |

| 1946 | 18,562 | +26.4% |

| 1951 | 19,678 | +6.0% |

| 1956 | 21,687 | +10.2% |

| 1961 | 21,228 | −2.1% |

| 1966 | 21,678 | +2.1% |

| 1971 | 23,816 | +9.9% |

| 1981 | 29,135 | +22.3% |

| 1986 | 30,608 | +5.1% |

| 1991 | 30,061 | −1.8% |

| 1996 | 30,195 | +0.4% |

| 2002 | 32,505 | +7.7% |

| 2006 | 35,090 | +8.0% |

| 2011 | 37,816 | +7.8% |

| 2016 | 39,004 | +3.1% |

| [48][49][50][51][52] | ||

Population by place of birth:

| Location | 2006[53] | 2011[54] | 2016[55] | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | 28,095 | 29,114 | 29,430 | +316 |

| UK | 3,488 | 3,839 | 3,791 | −48 |

| Poland | 252 | 555 | 602 | +47 |

| Lithuania | 421 | 633 | 657 | +24 |

| Other EU 28 | 692 | 1,119 | 1,508 | +389 |

| Rest of World | 1,804 | 2,269 | 2,652 | +383 |

Population by ethnic or cultural background:

| Ethnicity or culture | 2006[53] | 2011[56] | 2016[57] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Irish | 29,840 | 30,645 | 29,872 |

| White Irish Traveller | 325 | 441 | 535 |

| Other White | 1,802 | 2,987 | 3,572 |

| Black or Black Irish | 1,276 | 1,669 | 1,785 |

| Asian or Asian Irish | 372 | 687 | 988 |

| Other | 380 | 389 | 682 |

| Not stated | 757 | 711 | 1,206 |

Population by religion:

| Religion | 2002[58] | 2006[53] | 2011[59] | 2016[60] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 29,177 | 30,677 | 31,790 | 30,187 |

| Church of Ireland (incl. Protestant) | 482 | 527 | – | – |

| Church of Ireland, England, Anglican, Episcopalian | – | – | 590 | – |

| Apostolic or Pentecostal | – | – | 359 | – |

| Other Christian religion, n.e.s. | 415 | 480 | 714 | – |

| Presbyterian | 169 | 165 | 178 | – |

| Muslim (Islamic) | 279 | 436 | 569 | – |

| Orthodox (Greek, Coptic, Russian) | 44 | 171 | 399 | – |

| Methodist, Wesleyan | 84 | 66 | – | – |

| Other stated religions | 467 | 627 | 541 | 4,248 |

| No religion | 773 | 1,158 | 1,971 | 3,331 |

| Not stated | 615 | 778 | 705 | 1,238 |

Places of interest

Places of interest in North Louth within 15 km of Dundalk.

| Place | Description | Location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| County Museum Dundalk | The county museum documenting the history of County Louth. | 54°0′16.79″N 6°23′49.75″W | |

| St. Patrick's Church[61] | The site was acquired in 1834 with the building completed in 1847, but was in use from 1842. | 54°0′13.94″N 6°23′56.8″W | |

| St. Nicholas' Church (Roman Catholic)[61] | The site was levelled and the foundations cleared out in February 1859, dedication of the Church was in August 1860. Contains a shrine to the local born St. Bridget. | 54°0′35.03″N 6°24′9.1″W | |

| St Joseph's Redemptorist Church[62] | The community of Redemptorists, or missionary priests, settled here in 1876.[63] Contains a relic of St. Gerard Majella. | 54°0′15.2″N 6°23′21.8″W | |

| Parish Church of Saint Nicholas (Anglican Church of Ireland) | Known locally as the Green Church due to its green copper spire. Contains epitaph erected to the memory of Scotland's National Bard, Robert Burns and whose sister Agnes Burns/Galt and her husband William Galt who built Stephenstown Pond are buried here.[64] | 54°0′30.53″N 6°24′5.81″W |  |

| Priory of St Malachy, Dominican chapel | The 'Carlingford Dominicans' official foundation in Dundalk was in 1777[65] | 54°0′1.69″N 6°24′31.09″W | |

| Saint Brigid's Shrine[66][67] | 54°3′11.3″N 6°23′53.24″W | ||

| St Brigid's Well | Holy Well dedicated to St. Brigid | 54°3′6.09″N 6°23′2.06″W | |

| St Bridget's Church, Kilcurry | Holds a relic of St Bridget – a fragment of her skull was brought here in 1905 by Sister Mary Agnes of the Dundalk Convent of Mercy | 54°2′33.57″N 6°25′31.99″W | |

| Castle Roche | Norman castle, the seat of the De Verdun family, who built the castle in 1236 AD. | 54°2′47″N 6°29′18″W |  |

| Proleek Dolmen[68] | One of the finest examples of its kind in Ireland | 54°2′13.86″N 6°20′53.75″W | |

| Proleek Wedge Tomb | 54°2′12.84″N 6°20′49.88″W | ||

| Franciscan friary | Founded 1246[69] | 54°0′22.51″N 6°23′37.92″W |  |

| Windmill Tower | An eight-storey windmill-tower, built around 1800. | 54°0′21.14″N 6°23′21.22″W | |

| Our Lady's Well / Ladywell | Pattern takes place here on 15 August, during the feast of the assumption. | 53°59′36.91″N 6°24′8.23″W | |

| Cloghafarmore (Cuchulains / Cú Chulainn Stone) | Standing stone on which Cú Chulainn tied himself to after his battle with Lugaid in order to die on his feet, facing his enemies. | 53.974484°N 6.465991°W |  |

| Dromiskin Round Tower & High Crosses | Founded by a disciple of St Patrick, Lughaidh (unknown – 515AD) | 53°55′19.24″N 6°23′53.55″W | |

| Cú Chulainn Castle / Dun Dealgan Castle / Castletown Motte / Byrne's Folly | Built in the late 11th century by Bertram de Verdun, a later addition was the castellated house known as 'Byrne's Folly' built in 1780 by a local pirate named Patrick Byrne. | 54°0′49.77″N 6°25′48.82″W |  |

| Magic Hill | A place where the layout of the surrounding land produces the optical illusion that a very slight downhill slope appears to be an uphill slope. Thus, a car left out of gear will appear to be rolling uphill against gravity.[70] | 54°1′19.6″N 6°17′31.86″W | |

| Long Woman's Grave or "The Cairn of Cauthleen" | The grave of a Spanish noble woman, Cauthleen, who married Lorcan O’Hanlon, the youngest son of the "Cean" or Chieftain of Omeath.[71] Her grave is known as the "Lug Bhan Fada" (long woman's hollow).[71] | 54°3′40.63″N 6°16′28.85″W | |

| Rockmarshall Court Tomb | 14 metres long cairn. | 54°0′33″N 6°17′5″W | |

| Dunmahon Castle | Ruins of four storeys tower-house with vault over ground floor. In 1659 it was the residence of Henry Townley. | 53°57′27.48″N 6°25′19.4″W | |

| Haynestown castle | 3-storey square tower house with corner turrets | 53°57′36.47″N 6°24′40.85″W | |

| Milltown Castle | 15th-century Norman keep about 55 feet high built by the Gernon family. | 53°55′58.77″N 6°25′34.23″W | |

| Knockabbey Castle and Gardens | Originally built in 1399, the historical water gardens originally date from the 11th century. | 53°55′47.61″N 6°35′7.01″W | |

| Louth Hall Castle | Ruins originally built in the 14th century in gothic design, it was later extended in the 18th and 19th century in Georgian design. Home of the Plunkett family, Lords of Louth | 53°54′44.01″N 6°33′11.56″W | |

| Roodstown Castle | Dates from the 15th century, features two turrets. | 53°52′20.11″N 6°29′12.07″W | |

| Aghnaskeagh Cairn and Portal Tomb | 54°3′40.59″N 6°21′28.6″W | ||

| Faughart Round Tower | Remains of a monastery founded by St Moninna in the 5th century. | 54°3′6.11″N 6°23′4.18″W | |

| Grave of Edward Bruce | Proclaimed High King of Ireland before he was killed in the battle of Faughart in 1318 | 54°3′6.11″N 6°23′4.18″W | |

| Faughart Motte | 54°3′8.07″N 6°23′9.67″W | ||

| Kilwirra Church, Templetown | St Mary's Church at Templetown, associated with the Knights Templar founded in 1118 by Hugh de Payens. | 53°59′10.33″N 6°9′18.51″W | |

| Lady Well, Templetown | 53°59′14.74″N 6°9′10.79″W | ||

| Ardee Castle | The largest fortified medieval Tower House in Ireland or Britain, founded by Roger de Peppard in 1207, the current building was built in the 15th century by John St. Ledger. James II used it as his headquarters for a month prior to the Battle of the Boyne. | 53°51′18.43″N 6°32′19.7″W | |

| Hatch's Castle, Ardee | Medieval Tower House | 53°51′24.99″N 6°32′22.22″W | |

| Kildemock Church 'The Jumping Church' | 14th-century church built on the site of the Church of Deomog (Cill Deomog), under the control of the Knights Templar until 1540. | 53°50′8.96″N 6°31′14.28″W | |

| St Mary's Priory | Augustinian Priory stands on the site where St Mochta established a monastery in 528 CE. | 53°57′11.68″N 6°32′38.97″W | |

| St Mochta's House | 12th Century Church/Oratory. | 53°57′12.33″N 6°32′43.36″W | |

| St James' Well | 54°1′11.03″N 6°8′38.83″W | ||

| Liberties of Carlingford | Medieval Head Carving | 54°2′31.47″N 6°11′13.81″W | |

| The Mint of Carlingford | Mint established in 1467 | 54°2′25.06″N 6°11′11.02″W | |

| Tallanstown Motte | 53°55′15.12″N 6°32′59.53″W | ||

| Dominican Priory of Carlingford | Founded by Richard de Burgh in 1305 | 54°2′17.33″N 6°11′4.13″W | |

| King John's Castle (Carlingford) | Commissioned by Hugh de Lacy before 1186, the castle owes its name to King John (Richard the Lionheart's brother) who visited Carlingford in 1210. | 54°2′35.7″N 6°11′12.3″W |  |

| Carlingford Lough | A glacial fjord that forms part of the border between Northern Ireland to the north and Ireland to the south. On its northern shore is County Down and on its southern shore is County Louth. At its extreme interior angle (the northwest corner) it is fed by the Newry River and the Newry Canal. | 54°2′35.7″N 6°11′12.3″W |  |

| Ravensdale Forest, Ravensdale, County Louth | 54°03′08″N 6°20′23″W |  |

Festivals and culture

Music and arts

Dundalk has two photography clubs, Dundalk Photographic Society[72] and the Tain Photographic Club. In 2010 Dundalk Photographic Society won the FIAP Photography Club World Cup.[73]

Musical groups and organisations include the Fr. McNally Chamber Orchestra (which was created in April 2010),[74] and the Cross Border Orchestra of Ireland (CBOI) which is a youth orchestra based in the Dundalk Institute of Technology.[75] The latter maintains a membership of 160 musicians between the ages of 12 and 24 and was established in 1995 shortly after the implementation of the Peace Process. It tours regularly to Europe and America and has sold-out venues such as Carnegie Hall and Chicago Symphony Hall. The Clermont Chorale[76] was formed in 2003 and has 30 members, drawn from different parts of County Louth. Dundalk School of Music was created in 2010 and provides education in music for different ages and disciplines.[77]

Dundalk Gaol is the home of The Oriel Centre, a regional centre for Comhaltas Ceoltoirí Éireann.[78] It opened in 2010 and promotes traditional Irish music, song, dance and the Irish language.

Festivals

Festivals associated with Dundalk include the Brigid of Faughart Festival in February,[66] and the Carlingford National Leprechaun Hunt which is held in March.[79]

The Táin March festival, established in 2011, is a walking festival which seeks to commemorate the legendary Cattle Raid of Cooley (Táin Bó Cúailnge).[80] It is held in June, as is the Dundalk Youth Arts Festival.

In August, the All-Ireland Poc Fada Championship is held. Other events in the late summer and early Autumn include the Peninsula Ploughing & Field Day, Greenore Maritime Festival, the Knockbridge Vintage Rally & Family Fun Day,[81] and Saint Gerard Majella Novena[82]

The Dundalk Festival of Light & Culture and Ardee Baroque Festival are held over the winter period.[83]

Transport

Shipping services to Liverpool were provided from 1837 by the Dundalk Steam Packet Company.

Dundalk is an important stop along the Dublin–Belfast railway line, being the last station on the Republic side of the border. Its rail link to Dublin was inaugurated in 1849 and the line to Belfast was opened the following year. Further railway links opened to Derry by 1859 and Greenore in 1873.

In the 20th century, Dundalk's secondary railway links were closed: first the line to Greenore in 1951 and then that to Derry in 1957. In 1966 Dundalk railway station was renamed Dundalk Clarke Station after the Irish republican activist Tom Clarke, though it is still usually just called Dundalk Station. The station is served by the Dublin-Belfast "Enterprise" express trains as well as local Commuter services to and from Dublin. It also houses a small museum of railway history. Dundalk is the last train station on the line before crossing the border into Northern Ireland.

Dundalk's Bus Station is operated by Bus Éireann and located at Long Walk near the town centre.

Major infrastructure upgrades have taken place in and around Dundalk. These improvements have covered the road, rail and telecommunication infrastructures for—according to the National Development Plan—a better integration with the neighbouring Dublin, Midlands Gateway, and Cavan/Monaghan Hubs.

The M1 – N1/A1 connects Dundalk to Dublin and Newry. Works to extend it to Belfast were completed in July 2010.

Education

Primary education

Primary schools in Dundalk include a number of Irish language-medium schools (Gaelscoileanna) like Gaelscoil Dhún Dealgan.[84] There are approximately 20 English-medium national schools in the area, the largest of which include Muire na nGael National School (also known as Bay Estate National School) and Saint Joseph's National School, which (as of early 2020) had an enrollment of over 670 and 570 pupils respectively.[85][86][87]

Secondary schools

Secondary schools in the town include Coláiste Lú (an Irish medium secondary school or Gaelcholáiste),[88] De la Salle College, Dundalk Grammar School, St. Mary's College (also known as the Marist), O'Fiaich College,[89] Coláiste Rís, St. Vincent's Secondary School,[90] St. Louis Secondary School, and Coláiste Chú Chulainn.[91]

Tertiary education

Dundalk Institute of Technology (often abbreviated to DkIT) is the primary higher education provider in the north east of the country. It was established in 1970 as the Regional Technical College, offering primarily technician and apprenticeship courses.

The Ó Fiaich Institute of Further Education also offers further education courses.[92]

Media

The local newspapers are The Argus, Dundalk Democrat and Dundalk Leader.[93]

Online only media outlet includes Talk of the Town.[94]

The local radio station is Dundalk FM broadcasting on 97.7 FM,[95] with regional stations LMFM (Louth-Meath FM) on 96.5 FM, and iRadio (NE and Midlands) on 106.2FM also covering the area. UK Services from nearby Northern Ireland can also be clearly received.

Sport

Association football

Dundalk Football Club (/dʌnˈdɔːk/; Irish: Cumann Peile Dhún Dealgan) is a professional association football club. The club competes in the League of Ireland Premier Division, the top tier of Irish football, and are the reigning League Champions and League of Ireland Cup holders. Founded in 1903 as the works-team of the Great Northern Railway, they played in junior competition until joining the Leinster Senior League in 1922. After playing four seasons at that level, they were elected to the Free State League (which later became the League of Ireland) on 15 June 1926. They became the first club outside of Dublin to win the league title in 1932–33, and have won at least one league title or FAI Cup in every decade since. They are now the second most successful club in the League's history, and the most successful in the Premier Division era. The club has played at Oriel Park since moving from its original home at the Dundalk Athletic Grounds in 1936.

Rugby

Dundalk R.F.C. was formed in 1877 and has achieved a number of honours over its history. These include winning the Provincial Towns Cup on 10 occasions from 15 appearances. Dundalk is currently in the Leinster League Division 1A and field three senior teams plus youth and mini teams at all age groups, and a number of girls' tag teams.[96]

Ice hockey

The Dundalk Ice Dome (closed as of August 2012) was where local ice hockey team the Dundalk Bulls (now defunct) played. The Ice Dome hosted the IIHF World Championship of Division III in April 2007.[97]

Horse racing and greyhound racing

Both horse racing and greyhound racing are held at Dundalk Stadium. Ireland's first all-weather horse racing track was opened in August 2007 on the site of the old Dundalk racecourse.[98] The course held Ireland's first ever meeting under floodlights on 27 September 2007.

American football

Louth's only American Football team, the Louth Mavericks American Football Club[99] (Formerly Dundalk Mavericks), are based in Dundalk and were set up in 2012. They currently play in AFI Division 1. The club train at DKIT and play their matches at Dundalk Rugby Club. 2017 was the club's most successful year, going 5–3 and defeating the Craigavon Cowboys in the IAFL1 Bowl[100] to gain promotion to the top division for the first time in the club's history.[101]

Tennis

Dundalk also has a tennis club, The Dundalk Lawn Tennis and Badminton Club[102] was founded in 1913 and held the Senior Interprovincial Championships (inter-pros) on 29–31 August 2010.[103]

Cricket

Dundalk Cricket Club was founded in November 2009 and began playing matches in the 2010 season.[104] It was recognised by the cricket magazine The Wisden Cricketer as its "Club of the Month" for October 2010. This is both unusual for an Irish club and a club only twelve months into its existence. In 2011, the club was admitted into the Leinster Cricket Union and played in Leinster Senior League Division 11. In the 2011 season it won the Leinster League Division 11 Championship title and in the course of doing so became the only club in the whole of Leinster across the 14 divisions to go unbeaten. In the 2012 season the club won their second title as Leinster League Division 9 Champions.

Snooker

Dundalk & District Snooker League has been running for over 20 years. In 2010 the league was re-branded as the Dundalk Snooker League sponsored, by Tool-Fix. The league has attracted national recognition through RIBSA (Republic of Ireland Snooker and Billiards Association) and the CYMS Letterkenny, who have arranged a "ryder cup" style challenge match against the best players in the Dundalk Snooker League. As of the 2012 season, the league had 15 teams and 113 players competing in 6 championship events, 4 ranking events and 5 special events.[105]

Cycling

The first cycling club in Dundalk was founded in 1874. Cuchulainn Cycling Club[106] was formed in 1935 and is currently one of the biggest and most active cycling clubs in the country with over 300 members. The club caters for all disciplines of the sport including road, off-road and BMX. The club has acquired permission for the construction of a cycling park and 250m velodrome in Muirhevna Mor.[107]

Other sports

Dundalk Kayak Club, founded in 2005, operates from their clubhouse just outside Dundalk town. They cater for all levels of kayaker and run beginner courses twice yearly.

Dundalk held its first ever national fencing tournament in April 2007.[108]

Dundalk also has a basketball team, the Dundalk Ravens.

Gaelic football

Dundalk Gaels GFC (founded 1928) and Seán O'Mahony's GFC (founded 1938) both represent the town.

Politics and government

Louth County Council (Irish: Comhairle Contae Lú), County Hall, Millennium Centre, Dundalk[109] is the authority responsible for local government in Dundalk. As a county council, it is governed by the Local Government Act 2001. The council is responsible for housing and community, roads and transportation, urban planning and development, amenity and culture, and environment.[110] The council has 29 elected members, 13 of whom are from the Dundalk region. Elections are held every five years and are by single transferable vote.

For the purpose of elections the town is divided into two local electoral areas: Dundalk-Carlingford (6 Seats) and Dundalk South (7 Seats).[111]

Dundalk is represented in Dáil Éireann by the Louth parliamentary constituency.

Notable people

Arts and Media

- Peadar Ó Dubhda, Patriot, musician, politician, musician, and author of the first translation the Bible into Irish.[112][113]

- Paul Vincent Carroll (1900–1968), playwright who founded two theater groups in Glasgow, Scotland

- The Corrs, Celtic folk rock group and family (Andrea, Sharon, Caroline, and Jim Corr), born and raised in Dundalk

- Maria Cuche, singer who represented Ireland in the 1985 Eurovision Song Contest, finishing 6th

- The Flaws, indie rock band

- Catherine Gaskin (1929–2009), romance novelist

- Donald Macardle (1900–1984), actor, screenwriter, and director

- Dorothy Macardle (1889–1958), revolutionary, author and playwright

- Cathy Maguire, singer-songwriter; currently lives in the United States

- Dawn Martin, singer who represented Ireland in the 1998 Eurovision concert, finishing 9th

- Patrick McDonnell, actor in Naked Camera and Father Ted

- John Moore, film director, producer, and writer

- Brendan O'Dowda (1925–2002), Irish tenor who popularised the songs of Percy French

- Liam Reilly, singer who represented Ireland in the 1990 Eurovision Song Contest, finishing 2nd; singer in the group Bagatelle

- Jinx Lennon, Music Artist

- Thomas MacAnna (1926–2011), Tony Award-winning theatre director and playwright

- Molly Barton (1861-1949), artist

- Úna-Minh Kavanagh (born 1991), journalist and writer currently living in Dundalk

- Nuala Kennedy (1977–Present), artist

- Just Mustard (est. 2016), music group

Academia and Science

- Nicholas Callan, scientist who made the first induction coil; went to primary school here

- Thomas Coulter (1793–1843), botanist and doctor

- Richard FitzRalph (c. 1300 – 16 December 1360), Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford; Archbishop of Armagh from 1346 to 1360; his remains are interred at St Nicholas's Church

- John Phillip Holland, inventor of the submarine, worked as a teacher in Colaiste Ris, Dundalk

- Peter Kerley, radiologist known for describing Kerley lines of heart failure

- Peter Rice (1935–1992), engineer, worked on the Sydney Opera House, Louvre Pyramid and Centre Pompidou

- Laurie Winkless, physicist and science writer

- Fred Halliday, (1946–2010) writer and academic.

Politics

- Gerry Adams, Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth-Dundalk constituency since 2011

- Dermot Ahern, Fianna Fáil TD and former government minister

- Edward Haughey (1944–2014), entrepreneur and politician

- Brendan McGahon, former Fine Gael TD

Religion

- Saint Brigit of Kildare (c. 453 – c. 524)

Sport

- Tommy Byrne, former Formula 1 racing driver

- David Kearney, rugby player

- Rob Kearney, rugby player, current player for both Leinster and Ireland

- Jim McQuillan, Irish international darts player

- Steve Staunton, former football player and former Republic of Ireland national football team manager

- Tom Sharkey (1873–1953), heavyweight boxer

- Tommy Traynor (1933–2006), former footballer, Republic of Ireland national football team and Southampton FC left-back

Military

- Cú Chulainn, aka Sétanta

- Francis Leopold McClintock, Royal Navy Rear Admiral, Arctic explorer, discoverer of the fate of Franklin

Business

- Larry Goodman, entrepreneur in the beef industry. #22 on the Irish Independent Rich List 2017.[114]

- Dr Pearse Lyons, entrepreneur; President of Kentucky-based Alltech Inc.; proposed the sister cities twinning with the City of Pikeville, Kentucky. #5 on the Irish Independent Rich List 2017.[114]

- Henry McShane, established the McShane Bell Foundry; namesake of Dundalk, Maryland.

- Martin Naughton, entrepreneur founded GlenDimplex. #11 on the Irish Independent Rich List 2017.[114]

Other

- Agnes Burns, sister of the poet Robert Burns lived at Stephenstown with her husband William Galt between 1817 and 1834.

Twin towns and sister cities

Dundalk is twinned with the following places:

See also

- List of abbeys and priories in County Louth

- List of towns and villages in Ireland

- Dundalk, which existed until the Act of Union in 1800

- Dundalk, which existed 1801–1885

References

- "Dundalk - Carlingford and Mourne".

- "Dundalk". 20 March 2009.

- "eOceanic". www.inyourfootsteps.com.

- "Census 2011 – Population Classified by Area Table 6 – Population and area of each Province, County, City, urban area, rural area and Electoral Division, 2011 and 2006" (PDF). Census 2011, Volume 1 – Population Classified by Area. Central Statistics Office. 25 April 2012. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Settlement Dundalk". Central Statistics Office. 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Municipal District Dundalk". Central Statistics Office. 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Armit, Ian; England), Prehistoric Society (London; Belfast, Queen's University of (1 January 2003). Neolithic Settlement in Ireland and Western Britain. Oxbow Books. p. 34.

- "Five Louth Souterrains". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 19 (3): 206–217. 1979. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Kinsella, Thomas (1969). The Táin. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192810901.

- "St Brigid: 5 things to know about the iconic Irish woman". www.rte.ie. RTÉ. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. William Tempest. pp. 1–9. ISBN 1297871308.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1998). "Vikings in Ireland and Scotland in the Ninth Century" (PDF). Peritia. 12: 296–339. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. William Tempest. pp. 13–16. ISBN 1297871308.

- Connolly, S.J. (2007). Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923483-7.

- "Castle Roche, Co. Louth". www.archiseek.com. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Joyce, Patrick. "A Concise History of Ireland". www.libraryireland.com. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. William Tempest. p. 64. ISBN 1297871308.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. William Tempest. pp. 68–75. ISBN 1297871308.

- O'Sullivan, Harold (1 January 1977). "The Cromwellian and Restoration Settlements in the Civil Parish of Dundalk, 1649 to 1673". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 19 (1): 24–58. doi:10.2307/27729438. JSTOR 27729438.

- Systems, Adlib Information. "Internet Server 3.1.1". www.louthcoco.ie.

- Joseph Gavin and Harol O'Sullivan. Dundalk: A Military History. (Dundalk: Dundalgan Press Ltd., 1987), pp.109–137.

- Dundalk Gaol interpretive centre Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine website

- Harnden, Toby. Bandit Country: the IRA and South Armagh, pg. 73-5.

- "Dundalk locals win the battle to keep the economy of the town they love so well alive".

- Cowen, Brian (12 December 2000). Speaking in Dundalk at a public event with President Clinton (Speech). Dundalk, Ireland: Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Dundalk Digital Atlas | Earls of Roden, from the Jocelyn family Archived 2 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Fiona Gartland, "Freehold of Dundalk sold at auction" in The Irish Times dated 22 July 2006

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. p. 8.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. p. 10.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. p. 11.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. William Tempest. p. 21. ISBN 1297871308.

- D'Alton, John (1845). The history of Ireland: from the earliest period to the year 1245, Vol II. Published by the author. p. 49.

- "Battle of Dundalk, 14 October 1318". www.historyofwar.org.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. pp. 88.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. pp. 110.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. pp. 310.

- D'Alton, John (1864). The history of Dundalk and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the present time. William Tempest. pp. 174.

- "Battle of Courtbane attracts world media - Independent.ie".

- "Dundalk bombing report, Ludlow murder expected in few weeks - Independent.ie".

- "Home Page: The Dundalk Bombing, 19 December 1975". www.michael.donegan.care4free.net.

- "Coat of Arms (crest) of Dundalk". www.heraldry-wiki.com. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- Flood, W. H. Grattan (29 March 1899). "The De Verdons of Louth". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 9 (4): 417–419. JSTOR 25507007.

- "Heraldry of the world - Category:Irish municipalities". www.ngw.nl. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Dundalk's 1675 Seal". Evening Herald. 21 December 1938. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- D’Alton, John (1864). The History of Dundalk, and its environs; from the earliest period to the present time; with memoirs of its eminent men. Charleston SC, U.S.A.: British Library Historical Print Editions. p. 299.

- "Town Hall, Crowe Street, Dundalk, County Louth". buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Three Black Crows". Belfast Newsletter. 19 December 1930. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Census for post 1821 figures. Archived 20 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- NISRA – Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (c) 2013 Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Nisranew.nisra.gov.uk (27 September 2010). Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- "Dundalk Migration, Ethnicity and Religion (CSO Area Code LT 10008)". Central Statistics Office. 2006.

- "Dundalk Migration, Ethnicity and Religion (CSO Area Code LT 10008)". Central Statistics Office. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014.

- "Dundalk Migration, Ethnicity, Religion and Foreign Languages". Central Statistics Office. 2017.

- "Dundalk Migration, Ethnicity and Religion (CSO Area Code LT 10008)". Central Statistics Office. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014.

- "Usually resident population by ethnic or cultural background". Central Statistics Office. 2017.

- "Number of persons by religion (XLS 43KB), Row 147". Central Statistics Office. 2002.

- "Dundalk Migration, Ethnicity and Religion (CSO Area Code LT 10008)". Central Statistics Office. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014.

- "Population by religion". Central Statistics Office. 2017.

- "HISTORY". www.stpatricksparishdundalk.org.

- "About Us – St Joseph's Redemptorists Monastery". www.redemptoristsdundalk.ie.

- Tibus, Website design and development by. "St Joseph's Redemptorist Church - Attractions - Churches, Abbeys and Monasteries - All Ireland - Republic of Ireland - Louth - Dundalk - Discover Ireland". www.discoverireland.ie.

- "Robert Burns & the Louth connection". www.irishidentity.com.

- Priory of St Malachy, Dundalk | History

- "Home - Brigid of Faughart Festival - www.brigidoffaughart.ie". Brigid of Faughart.

- Tibus, Website design and development by. "Saint Brigid's Shrine and Well Faughart - Attractions - Churches, Abbeys and Monasteries - All Ireland - Republic of Ireland - Louth - Dundalk - Discover Ireland". www.discoverireland.ie.

- Tibus, Website design and development by. "Proleek Dolmen - Attractions - Museums and Attractions - All Ireland - Republic of Ireland - Louth - Dundalk - Discover Ireland". www.discoverireland.ie.

- Franciscan friary Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Can Things Roll Uphill?". math.ucr.edu.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Welcome to Dundalk Photographic Society". www.dundalkphoto.com.

- FIAP 5th Club World Cup Results Page Archived 21 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fr. McNally Chamber Orchestra". www.facebook.com.

- The Cross Border Orchestra of Ireland Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Clermont Chorale". www.facebook.com.

- Dundalk School of Music Archived 2 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Home – Oriel Centre. Orielcentre.ie. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- "Carlingford & Cooley Peninsula - Official Destination Website". Carlingford & Cooley Peninsula.

- "Home - The Táin March Festival - Ireland's Ancient East". www.tainmarch.ie.

- "Knockbridge Vintage Club – Our Club Website". www.knockbridgevintageclub.com.

- "St Gerard's Novena gets underway in Dundalk this Sunday - Talk of the Town". Talk of the Town. 7 October 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Programme for Ardee Baroque 2012 – Create Louth". www.createlouth.ie.

- Gaelscoil Dhún Dealgan Archived 29 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.education.ie/en/Find-a-School/School-List/?level=Primary&geo=Louthðos=-1&lang=-1&gender=-1

- https://www.education.ie/en/find-a-school/School-Detail/?roll=19598V

- https://www.education.ie/en/find-a-school/School-Detail/?roll=19673J

- Coláiste Lú

- "O'Fiaich College, Secondary School".

- "St. Vincent's Secondary School".

- "Home". colaistecc.ie.

- "O Fiaich Institute of Further Education Dundalk". www.ofi.ie.

- "Dundalk Leader". www.dundalkleader.com.

- "Talk of the Town - News from Dundalk and north Louth". Talk of the Town.

- "Dundalk FM » Dundalk's Local Community Radio Station". Dundalk FM.

- "Dundalk Rugby Football Club". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- AG, Novanet Internet Consulting. "2007 IIHF World Championship Div III". www.iihf.com.

- RTE – 2007 Irish Racing Archived 4 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Louth Mavericks AFC". www.facebook.com.

- Match Report

- "Dundalk Lawn Tennis and Badminton Club". www.dundalkracketsclub.com.

- Welcome to Dundalk Lawn Tennis and Badminton club. Dundalkracketsclub.com. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- Dundalk Cricket Club home page Archived 9 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Dundalkcricketclub.com. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- Dundalk Snooker League Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Dundalk Snooker League. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- "Cuchulainn Cycling Club - Catering for all Cyclists in Louth". www.dundalkcycling.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dundalk Institute of Technology | Sport>

- "Home - Louth County Council". www.louthcoco.ie.

- "Services". Louth County Council. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- "2014 Local elections – Louth County Council". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- "State of Dundalk great's grave a source of anger and embarrassment". www.dundalkdemocrat.ie. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Town lost one of its most distinguished sons with death of novelist, playwright and musician, Peadar O'Dubhda". independent. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Rich List 2017". Irish Independent. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Dundalk – Reze twinning page Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Dundalk agrees to twin with Pikeville, Kentucky - Independent.ie".