Dundalk Distillery

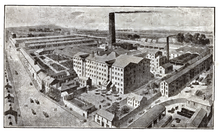

The Dundalk Distillery was an Irish whiskey distillery that operated in Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland between 1708 and 1926.[3] It is thought to have been one of the old registered distilleries in Ireland.[3] Two of the distillery buildings, the grain store and maltings, still exist and now house the County Museum and Dundalk Library.[3]

| Location | Dundalk |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 54°00′16.6″N 6°23′49.5″W |

| Owner | Malcolm Brown & Co. |

| Founded | 1708 |

| Founder | James Gillichan/Gilleghan and Peter Godbey |

| Status | Defunct |

| Water source | Corthill Lough[1] |

| No. of stills | 4 pot stills (2 x 10,700 gallon wash stills, an 8,000 gallon low-wines still, a 6,000 gallon spirit still) and a Coffey still[1] |

| Capacity | possibly 1,000,000 gallons[2] |

| Mothballed | 1926[3] |

The distillery was used as a navigation point by seamen due to its two large chimney stacks, one of which was the largest in Ireland when it was built in 1817.[3]

History

Dundalk was home to a number of distilleries down through the years. The most notable of which was established in 1780 by James Gilleghan and Peter Godbey at Roden Place on the site of an old tannery and bleach ground. Subsequently, several Scotsmen joined the company.[4] In 1802, the distillery is recorded as operating a 1,514 gallon still, which was quite large for the time.[5] By 1804, the distillery is reported as being operated by James Reid, Malcolm Brown, James Gilleghan, Peter Godbey and William Hamilton.[4] By 1807, the large still, the operation of which was impractical due to the licensing system, had been replaced by a smaller, 520 gallon still.[5] In 1812, Brown married Gillichan's daughter, subsequently gaining control of the company and on the death of his partners, after which the operation became known as Malcolm Brown & Co.[6]

In 1817, Dundalk and its surrounds suffered from a scarcity of food due to a bad harvest. That year, the owners of the distillery, having large stores of grain, generously had the stock ground into meal and sold at a rate which the poor could afford.[7] In the same year, a 162 ft tall, brick chimney stack was constructed at the distillery in that year (visible in the image above), which was the largest in Ireland at the time.[3] Prior to the reform the excise regulations in 1823, distillation was based on the theoretical output of a pot still. The purpose of the large chimney was to allow firing of the pot still in the shortest possible time.[8]

In 1823, Malcolm Brown, then in the trade "nearly twenty years" gave testimony to a British House of Commons inquiry into distilling regulations in Ireland. In his testimony, given in June 1823, Brown stated that his operations had lost money for the preceding two years due to increased competition from illicit unlicensed distillers, which had increased eight- to ten-fold in number in the Dundalk region over the same period.[9] As a result, Brown had ceased distilling at Dundalk the previous December, and that had no intention of resuming operations until the excise regulations were reformed.[9] At the time, Brown stated that illicit spirits could be obtained for 4 - 5 shillings a gallon, and were the duty reduced to 2 shillings sixpence, licit spirit could be sold at around 5 - 6 shillings a gallon.[9] With reduced duties, Brown stated that the price difference between licit and illicit spirits would narrow, prompting consumers to opt for licit spirits rather than risk a penalty by purchasing illicit spirit.[9] Brown stated that whiskey from Dundalk distillery was principally consumed in nearby counties of Armagh, Cavan and Down, and that some of his matured spirit sold at 12 shillings a gallon.[9]

Records show that by 1837, the distillery was consuming 40,000 barrels of grain a year, with a staff of 100, and an output of 300,000 gallons of spirit a year (up from 285,000 gallons in 1826).[1][10] The distillery prospered, and expanded further through the mid-1800s, with output more than doubling, in part due to the installation of a large Coffey still, becoming one of the most successful distilleries in the country.[3]

In 1854, Brown passed away without a son, and the distillery passed to his nephews, the Murrays.[6] When Alfred Barnard, a British historian, visited the distillery in 1886, output had reached close to 700,000 gallons per annum.[1] Barnard noted that much of the output from the distillery, was consumed locally, with the remainder exported to England and Scotland.[1] At the time of Barnard's visit, the distillery was being run three brothers (John, Malcolm, and Henry Murray) whose granduncle had come to control the distillery around 1800.[1]

On 22 November 1862, a fire broke out in a corn kiln in the grain stores of the distillery, completely destroying the building which contained several thousand tonnes of grain. After a raising of the alarm, 500 men of the 15th, the King's Hussars (a cavalry regiment), along with fire engines and other constabulary rushed to the scene, preventing the fire from spreading further. At the time, the bonded storehouses contained 400,000 gallons of whiskey. It was estimated that the fire caused £10,000 of damages and 100 redundancies. Unfortunately, one life was lost and several endangered after the incident, as during their efforts some of the hussars had consumed fusel oils, mistaking it for whiskey.[11][12]

By 1887, with a Coffey still employed alongside the existing pot stills, the distillery output had reached 700,000 proof gallons per annum.[5] At this point, the distillery was well equipped with a cooperage and workshops for engineers, carpenters, smiths etc., and had a payroll of about 100 men.[5] However, by the late 1800s, it appears that the distillery was experiencing financial difficulties, as an experienced external manager was recruited in 1898.[3] For a period of time, the distillery found some success by focusing on the production of grain spirit, with yeast a lucrative by-product which was exported to England under the name of "Skylark".[2][5] It is thought that at this stage production of pot still whiskey had ceased.[5] This focus on yeast resulted in the production of an industrial spirit which the distillery was happy to off-load on the London market at a low price, a fact which disturbed the Distillers Company of Scotland (DCL), as their competing product was being undersold.[5] However, as with many Irish distilleries, the distillery experienced further difficulties in the early 1900s, and in 1912, the distillery's owners decided to sell out and approached the United Distillers Company of Belfast, who offered to purchase the distillery in exchange for shares.[5] However, wanting cash, the owners eventually accepted a competing of £160,000 from DCL, who had interest in acquiring the distillery as it would end supply of industrial spirit outside the control of the DCL group.[3][5]

Under DCL ownership, production continued at Dundalk Distillery until 1926, when after 218 years, distilling stopped, the partition of Ireland in 1922 possibly hastening its demise.[6][2] In 1927, the Irish Government entered negotiations with DCL with regard to re-opening the distillery in the interests of local employment. However, DCL stated that the distillery was uneconomic to work as the majority of product was exported to London, and that re-opening could only be reconsidered if they were offered an increased drawback on exports of spirits, and an import tariff on yeast. However, this proposal was rejected, and operations were wound up for good in 1929.[5]

In the years that followed, the main chimney was demolished, with the bricks used to construct nearby houses, while many of the distillery buildings were either demolished or left vacant.[3] In the 1932, P.J. Carroll, the tobacco firm, purchased the grain store for use as a warehouse or bond store.[8] In the 1960s, this was donated to Dundalk Urban Council for use as an exhibition centre.[8] In 1994, this became home to the County Museum.[8] Another distillery building now houses Dundalk Public Library.[13]

Subsequent distilleries in Dundalk

John Teeling, founder of the Cooley Distillery, announced plans to redevelop the Great Northern Brewery in Dundalk as distilling complex in a €35 million investment.[14] The site was previously owned by Diageo and used mainly to brew Harp Lager. When complete the site will have a capacity to produce 3 million cases per annum, making it the second largest in Ireland. It will cater mainly for the third party market, a market Cooley catered for prior to its takeover by Beam Inc. (now Beam Suntory).[15]

In July 2015, distillation began at one of the two distilleries planned for the site following a €10 million investment.[16]

Bibliography

- Barnard, Alfred (1887). The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom. London: The Proprietors of "Harper's Weekly Gazette".

- McGuire, Edward B. (1973). Irish Whiskey: A History of Distilling, the Spirit Trade and Excise Controls in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and MacMillan. pp. 360–361. ISBN 0717106047.

- Townsend, Brian (1997–1999). The Lost Distilleries of Ireland. Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 1897784872.

References

- Barnard, Alfred (1887). The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom. London: The Proprietors of "Harper's Weekly Gazette".

- Dublin, Cork and South of Ireland: A Literary, Commercial & Social Review Past and Present; With a Description of Leading Mercantile Houses and Leading Enterprises. London: Stratten & Stratten. 1892. p. 130.

- Townsend, Brian (1997–1999). The Lost Distilleries of Ireland. Glasgow, Scotland: Neil Wilson Publishing. ISBN 1-897784-87-2.

- "Journals of the House of Commons". HMSO. 61: 799. 1806.

- McGuire, Edward B. (1973). Irish Whiskey: A History of Distilling, the Spirit Trade and Excise Controls in Ireland. Glasgow: Gill and MacMillan. pp. 360–361. ISBN 0717106047.

- Flynn, Charles (November 2000). "Dundalk 1900-1960: an oral history" (PDF). maynoothuniversity.ie. National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- The History of Dundalk, and Its Environs: From the Earliest Historic Period to the Present Time, with Memoirs of Its Eminent Men. Dundalk: William Tempest. 1864. p. 223.

- "Celebrating 20 years". www.dundalkmuseum.ie. Dundalk Museum. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Supplement to the 5th Report: Intercourse In Spirits ; Ordered, by the House of Commons, to Be Printed, 25 June 1823. London: Commissioners of Inquiry into the Collection and Management of the Revenue Arising in Ireland, etc. 1823. pp. 41–48.

- "Accounts relating to Malt and Spirits in Ireland and Scotland, 1826-27". HMSO: 605–608. 1828 – via Enhanced British Parliamentary Papers on Ireland.

- "Fire at the Dundalk Distillery - Great Loss of Property". The Dublin Evening Post. 25 November 1862.

- "NEW ZEALANDER, VOLUME XIX, ISSUE 1791, 11 FEBRUARY 1863". New Zealander. 11 February 1863. Retrieved 12 January 2017 – via https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- "Dundalk Branch and Louth County Library HQ". www.librarybuildings.ie/. Public Library Buildings. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Projects". www.gndireland.com. Great Northern Distillery. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "Irish Whiskey Company acquires Diageo Dundalk brewery". 22 August 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- "The Stills are alive in Dundalk with completion of €10m whiskey distilling development". 31 July 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2017.