Siege of Damascus (1148)

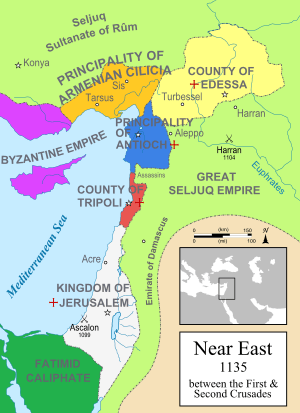

The Siege of Damascus took place between 24 and 28 July 1148, during the Second Crusade. It ended in a decisive crusader defeat and led to the disintegration of the crusade. The two main Christian forces that marched to the Holy Land in response to Pope Eugene III and Bernard of Clairvaux's call for the Second Crusade were led by Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. Both faced disastrous marches across Anatolia in the months that followed, with most of their armies being destroyed. The original focus of the crusade was Edessa (Urfa), but in Jerusalem, the preferred target of King Baldwin III and the Knights Templar was Damascus. At the Council of Acre, magnates from France, Germany, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem decided to divert the crusade to Damascus.

The crusaders decided to attack Damascus from the west, where orchards of Ghouta would provide them with a constant food supply. Having arrived outside the walls of the city, they immediately put it to siege, using wood from the orchards. On 27 July, the crusaders decided to move to the plain on the eastern side of the city, which was less heavily fortified but had much less food and water. Nur ad-Din Zangi arrived with Muslim reinforcements and cut off the crusaders' route to their previous position. The local crusader lords refused to carry on with the siege, and the three kings had no choice but to abandon the city. The entire crusader army retreated back to Jerusalem by 28 July.

Second Crusade

The two main Christian forces that marched to the Holy Land in response to Pope Eugene III and Bernard of Clairvaux's call for the Second Crusade were led by Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. Conrad's force included Bolesław IV the Curly and Vladislaus II of Bohemia, as well as Frederick of Swabia, his nephew who would become Emperor Frederick I.[1] The crusade had been called after the fall of the County of Edessa on 24 December 1144. The crusaders marched across Europe and arrived at Constantinople in September and October 1147.[2]

Both faced disastrous marches across Anatolia in the months that followed, and most of their armies were destroyed. Louis abandoned his troops and travelled by ship to the Principality of Antioch, where his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine's uncle, Raymond, was prince. Raymond expected him to offer military assistance against the Seljuk Turks threatening the principality, but Louis refused and went to Jerusalem to fulfil his crusader vow.[3] Conrad, stricken by illness, had earlier returned to Constantinople, but arrived in Jerusalem a few weeks later in early April 1148.[4] The original focus of the crusade was Edessa, but in Jerusalem, the preferred target of King Baldwin III and the Knights Templar was Damascus.[5]

Council of Acre

The Council of Acre was called with the Haute Cour of Jerusalem at Acre on 24 June. This was the most spectacular meeting of the Cour in its existence: Conrad, Otto of Freising, Henry II, Duke of Austria, Welf VI, future emperor Frederick, and William V, Marquess of Montferrat represented the Holy Roman Empire.[6] Louis, Thierry of Alsace, and various other ecclesiastical and secular lords represented the French. From Jerusalem King Baldwin, Queen Melisende, Patriarch Fulk, Robert de Craon (master of the Knights Templar), Raymond du Puy de Provence (master of the Knights Hospitaller), Manasses of Hierges (constable of Jerusalem), Humphrey II of Toron, Philip of Milly, Walter I Grenier, and Barisan of Ibelin were among those present.[7] Notably, no one from Antioch, Tripoli, or the former County of Edessa attended. Both Louis and Conrad were persuaded to attack Damascus.[2]

Some of the barons native to Jerusalem pointed out that it would be unwise to attack Damascus, as the Burid dynasty, though Muslim, were their allies against the Zengid dynasty. Imad ad-Din Zengi had besieged the city in 1140, and Mu'in ad-Din Unur, a Mamluk acting as vizier for the young Mujir ad-Din Abaq, negotiated an alliance with Jerusalem through the chronicler Usama ibn Munqidh. Conrad, Louis, and Baldwin insisted, Damascus was a holy city for Christianity. Like Jerusalem and Antioch, it would be a noteworthy prize in the eyes of European Christians. In July their armies assembled at Tiberias and marched to Damascus, around the Sea of Galilee by way of Baniyas. There were perhaps 50,000 troops in total.[8]

The general view now appears to be that the decision to attack Damascus was somewhat inevitable. Historians, such as Martin Hoch, regard the decision as the logical outcome of Damascene foreign policy shifting into alignment with the Zengid dynasty. King Baldwin III had previously launched a campaign with the sole objective of capturing the city. This damaged the Burid dynasty's relations with the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[9]

Fiasco at Damascus

The crusaders decided to attack Damascus from the west, where orchards of Ghouta would provide them with a constant food supply.[2] They arrived at Darayya on 23 July, with the army of Jerusalem in the vanguard, followed by Louis and then Conrad in the rearguard. The densely cultivated gardens and orchards would prove to be a serious obstacle for the crusaders.[10] According to William of Tyre, the crusader army was prepared for battle:

At Daria [Darayya], since the city was now so near, the sovereigns drew up their forces in battle formation and assigned the legions to their proper places in the order of march...Because of its supposed familiarity with the country, the division led by the King of Jerusalem was, by common decision of the princes, directed to lead the way and open a path for the legions following. To the King of the Franks [Louis VII] and his army was assigned the second place or centre that they might aid those ahead if the need arose. By the same authority, the Emperor [Konrad III] was to hold the third or rear position, in readiness to resist the enemy if, perchance an attack should be made from behind.[11]

The Muslims were well prepared and constantly attacked the army advancing through the orchards outside Damascus on 24 July. These orchards were defended by towers and walls and the crusaders were constantly pelted with arrows and lances along the narrow paths.[3]

On Saturday 24 July the crusaders began with an attack in the morning along the banks of the Barada river,[12] as far as al-Rabweh. There was a ferocious combat in the orchards and narrow roads at Mezzeh,[13] between the Christian force and a mixture of professional troops of Damascus, the ahdath militia and Turkoman mercenaries.[12] William of Tyre reported:

The cavalry forces of the townsmen and those who had come to their assistance realized that our army was coming through the orchards in order to besiege the city and they accordingly approached the stream which flowed into the town. This they did with their bows and their balistas [crossbows] so that they could fight off the Latin army...The emperor [Konrad], in command of the forces following, demanded to know why the army did not advance. He was told the enemy was in possession of the river and would not allow our forces to pass. Enraged at this news, Konrad and his knights galloped swiftly forward through the king's lines and reached the fighters who were trying to win the river. Here all leaped down from their horses and become foot soldiers, as is the custom of the Teutons when a desperate crisis occurs.[14]

The historian David Nicolle wrote that William of Tyre did not explain how Conrad was able to bring his forces up from the rear to the front without totally disorganizing the Christian army".[12] According to Syrian chronicler Abu Shama:

Despite the multitude of ahdath [militia], Turks, and common people of the town, volunteers and soldiers who had come from the provinces and had joined with them, the Muslims were overwhelmed by the enemy's numbers and were defeated by the infidels. The latter crossed the river, found themselves in the gardens and made camp there...The Franks...cut down trees to make palisades. They destroyed the orchards and passed the night in these tasks.[15]

Thanks to a charge by Conrad, the crusaders managed to fight their way through and chase the defenders back across the Barada river and into Damascus.[15]

Having arrived outside the walls of the city, they immediately put it to siege, using wood from the orchards. The crusaders began to build their siege position opposite Bab al-Jabiya where the Barada did not run past Damascus.[15] Inside the city the inhabitants barricaded the major streets, preparing for what they believed to be an inevitable assault.[3] Unur had sought help from Saif ad-Din Ghazi I of Mosul and Nur ad-Din Zangi of Aleppo, and led an attack on the crusader camp; the crusaders were pushed back from the walls into the orchards, where they were prone to ambushes and guerrilla attacks. During the counter-attack on Sunday, 25 July, the Damascus forces took heavy losses which included the 71-year-old lawyer and well known scholar named Yusuf al-Findalawi, the Sufi mystic Al-Halhli and soldier Nur al-Dawlah Shahinshah.[16] According to William of Tyre, on 27 July the crusaders decided to move to the plain on the eastern side of the city, opposite Bab Tuma and Bab Sharqi, which was less heavily fortified but had much less food and water.[2] During a raid on the crusader camp on 26 July, according to Abu Shama:

A large group of inhabitants and villagers...put to flight all the sentries, killed them, without fear of danger, taking the heads of all the enemy they killed and wanting to touch these trophies. The numbers of heads they gathered was considerable.[17]

There were conflicts in both camps: Unur could not trust Saif ad-Din or Nur ad-Din not to conquer the city if their offer of help was accepted; and the crusaders could not agree about who would receive the city if they captured it. Guy Brisebarre, lord of Beirut, was the suggestion of the local barons, but Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders, wanted it for himself and was supported by Baldwin, Louis, and Conrad. It was recorded by some that Unur had bribed the leaders to move to a less defensible position, and that Unur had promised to break off his alliance with Nur ad-Din if the crusaders went home.[3] Meanwhile, Nur ad-Din and Saif ad-Din had by now arrived at Homs and were negotiating with Unur for possession of Damascus, something that neither Unur nor the crusaders wanted. Saif ad-Din apparently also wrote to the crusaders, urging them to return home. With Nur ad-Din in the field it was impossible to return to their better position.[3] The local crusader lords refused to carry on with the siege, and the three kings had no choice but to abandon the city.[2] First Conrad, then the rest of the army, decided to retreat back to Jerusalem on 28 July, though throughout their retreat they were followed by Turkish archers who constantly harassed them.[18]

Aftermath

Each of the Christian forces felt betrayed by the other.[2] A new plan was made to attack Ascalon but this was abandoned due to the lack of trust that had resulted from the failed siege. This mutual distrust would linger for a generation due to the defeat, to the ruin of the Christian kingdoms in the Holy Land. Following the battle, Conrad returned to Constantinople to further his alliance with Manuel I Komnenos. As a result of the attack, Damascus no longer trusted the crusaders, and the city was formally handed over to Nur ad-Din in 1154. Bernard of Clairvaux was also humiliated, and when his attempt to call a new crusade failed, he tried to disassociate himself from the fiasco of the Second Crusade altogether.[19]

Notes

- Runciman (1952) p. 211.

- Riley-Smith (1991) p. 50.

- Brundage (1962) pp. 115–121.

- Riley-Smith (1991) pp. 49–50.

- Brundage

- Freed 2016, pp. 51–53.

- William of Tyre wrote "it seems well worth while and quite in harmony with the present history that the names of the nobles who were present at the council...should be recorded here for the benefit of posterity." He lists these and numerous others; "to name each one individually would take far too long." A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, trans. E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey (Columbia University Press, 1943), vol. 2, bk. 17, ch. 1, pp. 184–185.

- Runciman (1952) pp. 228–229.

- Hoch (2002)

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London page 57

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London pages 57–58

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London page 58

- Burns (2007) p. 153.

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London pages 58–59

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London page 59

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London page 67

- Nicolle, David The Second Crusade, Osprey: London page 71

- Baldwin (1969) p. 510.

- Runciman (1952) pp. 232–234 and p. 277.

References

- Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W., eds. (1969) [1955]. A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-04834-9.

- Brundage, James (1962). The Crusades: A Documentary History. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press.

- Burns, Ross (2007). Damascus: A History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-488490.

- Hoch, Martin & Jonathan Phillips – editors (2002). The Second Crusade: Scope and Consequences. Manchester: Manchester University Press.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Freed, John (2016). Frederick Barbarossa: The Prince and the Myth. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-122763.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicolle, David (2009). The Second Crusade 1148 Disaster outside Damascus. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-354-4.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). Atlas of the Crusades. New York: Facts on File.

- Runciman, Steven (1952). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smail, R. C. (1956). Crusading Warfare 1097–1193. Barnes & Noble Books.

Further reading

- The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusaders, extracted and translated from the Chronicle of Ibn al-Qalanisi. Edited and translated by H. A. R. Gibb. London, 1932.

- William of Tyre. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. Edited and translated by E. A. Babcock and A. C. Krey. Columbia University Press, 1943.

External links

- Kenneth Setton, ed. – A History of the Crusades, vol. I. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1958. Retrieved on 27 March 2008

- William of Tyre – The Fiasco at Damascus (1148) at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Retrieved on 27 March 2008