Historical reliability of the Quran

Historical reliability of the Quran concerns the question of the historicity of the described or claimed events in the Quran.

The Quran is viewed to be the scriptural foundation of Islam and is believed by Muslims to have been sent down by Allah (God) and revealed to Muhammad by the angel Jabreel (Gabriel). Muslims have generally disapproved of the historical criticism of the Quran, just as devout Christians and Jews have rejected similar Biblical criticism of their holy books.[1] It has been practiced primarily by secular, Western scholars such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, and Michael Cook, who set aside doctrines of the Quran's divinity, perfection, unchangeability, etc., accepted by Muslim scholars,[2] and instead investigate the Quran's origin, text, composition, and history.[2]

In the Muslim world, scholarly criticism of the Quran can be considered an apostasy and can be punished by death.[3] Scholarly criticism of the Quran, is thus, a beginning area of study in the Islamic world.[4][5]

Scholars have identified several pre-existing sources for the Quran.[6] The Quran assumes its readers' familiarity with the Christian Bible and there are many parallels between the Bible and the Quran. Aside from the Bible, the Quran includes legendary narratives about Alexander the Great, apocryphal gospels,[7] and Jewish legends. Thus, the question of the historical reliability of the Quran is tied to the question of the historical reliability of the Bible.

Textual history

Early manuscripts

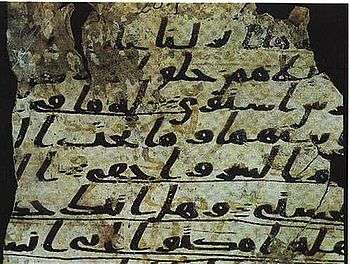

In the 1970s, 14,000 fragments of Quran were discovered in the Great Mosque of Sana'a, the Sana'a manuscripts. About 12,000 fragments belonged to 926 copies of the Quran, the other 2,000 were loose fragments. The oldest known copy of the Quran so far belongs to this collection: it dates to the end of the 7th–8th centuries.

The German scholar Gerd R. Puin has been investigating these Quran fragments for years. His research team made 35,000 microfilm photographs of the manuscripts, which he dated to early part of the 8th century. Puin has not published the entirety of his work, but noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography. He also suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests which had been reused. Puin believed that this implied an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.[8]

In 2015, some of the earliest known Quranic fragments, dating from between approximately AD 568 and 645, were identified at the University of Birmingham.[9] Islamic scholar Joseph E. B. Lumbard of Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar has written in the Huffington Post in support of the dates proposed by the Birmingham scholars. Professor Lumbard notes that the discovery of a Qur'anic text that may be confirmed by radiocarbon dating as having been written in the first decades of the Islamic era, and includes variations in the “under text.” recorded in the Islamic historiographical tradition . [10]

Quran and History

Creation narrative and the Flood

The Quran contains a creation narrative and refers to the world being created in six days. In Sūrah al-Anbiyāʼ, the Quran states that "the heavens and the earth were of one piece" before being parted.[11] God then created the landscape of the earth, placed the sky above it as a roof, and created the day and night cycles by appointing an orbit for both the sun and moon.[12] Some Muslim apologists, like Zakir Naik and Adnan Oktar advocate creationism. Some British Muslim students have distributed leaflets on campus, advocating against Darwin's theory of evolution[13] and contemporary Islamic scholar Yasir Qadhi believes that the idea that humans evolved is against the Quran.[14] It has to be noted, however, that not all Muslims are against the theory of evolution. Evolution is taught in many Islamic countries, and some scholars have tried to reconcile the Quran and evolution.[15]

Quran also contains the flood narrative. According to the Quran, Noah was a prophet for 950 years[16], and he built an ark where he filled it with pairs of animals.[17] People who did not believe him, including one of his own sons, are said to have drowned.[18]

Samiri

Quran recounts a story of the golden calf, where it mentions that Samiri, a rebellious follower of Moses, created the calf while Moses was away for 40 days on Mount Sinai, receiving the Ten Commandments.[19] Due to the fact that as-Samiri can mean the Samaritan,[20] some believe that his character is a reference to the worship of the golden calves built by Jeroboam of Samaria, conflating the two idol-worshiping incidents into one.

Alexander the Great legends

Quran also employs popular legends about Alexander the Great called Dhul-Qarnayn ("he of the two horns") in the Quran. The story of Dhul-Qarnayn has its origins in legends of Alexander the Great current in the Middle East in the early years of the Christian era. According to these the Scythians, the descendants of Gog and Magog, once defeated one of Alexander's generals, upon which Alexander built a wall in the Caucasus mountains to keep them out of civilised lands (the basic elements are found in Flavius Josephus). The legend went through much further elaboration in subsequent centuries before eventually finding its way into the Quran through a Syrian version.[21]

The reasons behind the name "Two-Horned" are somewhat obscure: the scholar al-Tabari (839-923 CE) held it was because he went from one extremity ("horn") of the world to the other,[22] but it may ultimately derive from the image of Alexander wearing the horns of the ram-god Zeus-Ammon, as popularised on coins throughout the Hellenistic Near East.[23] The wall Dhul-Qarnayn builds on his northern journey may have reflected a distant knowledge of the Great Wall of China (the 12th century scholar al-Idrisi drew a map for Roger of Sicily showing the "Land of Gog and Magog" in Mongolia), or of various Sassanid Persian walls built in the Caspian area against the northern barbarians, or a conflation of the two.[24]

Dhul-Qarneyn also journeys to the western and eastern extremities ("qarns", tips) of the Earth.[25] In the west he finds the sun setting in a "muddy spring", equivalent to the "poisonous sea" which Alexander found in the Syriac legend. [26] In the Syriac original Alexander tested the sea by sending condemned prisoners into it, but the Quran changes this into a general administration of justice.[26] In the east both the Syrian legend and the Quran have Alexander/Dhul-Qarneyn find a people who live so close to the rising sun that they have no protection from its heat.[26]

"Qarn" also means "period" or "century", and the name Dhul-Qarnayn therefore has a symbolic meaning as "He of the Two Ages", the first being the mythological time when the wall is built and the second the age of the end of the world when Allah's shariah, the divine law, is removed and Gog and Magog are to be set loose.[27] Modern Islamic apocalyptic writers, holding to a literal reading, put forward various explanations for the absence of the wall from the modern world, some saying that Gog and Magog were the Mongols and that the wall is now gone, others that both the wall and Gog and Magog are present but invisible.[28]

Death of Jesus

Quran maintains that Jesus was not actually crucified and did not die on the cross. The general Islamic view supporting the denial of crucifixion was probably influenced by Manichaenism (Docetism), which holds that someone else was crucified instead of Jesus, while concluding that Jesus will return during the end-times.[30]

That they said (in boast), "We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah";- but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them, and those who differ therein are full of doubts, with no (certain) knowledge, but only conjecture to follow, for of a surety they killed him not:-

Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself; and Allah is Exalted in Power, Wise;-

Despite these views, scholars have maintained, that the Crucifixion of Jesus is a fact of history and not disputed.[32] The view that Jesus only appeared to be crucified and did not actually die predates Islam, and is found in several apocryphal gospels.[33]

Irenaeus in his book Against Heresies describes Gnostic beliefs that bear remarkable resemblance with the Islamic view:

He did not himself suffer death, but Simon, a certain man of Cyrene, being compelled, bore the cross in his stead; so that this latter being transfigured by him, that he might be thought to be Jesus, was crucified, through ignorance and error, while Jesus himself received the form of Simon, and, standing by, laughed at them. For since he was an incorporeal power, and the Nous (mind) of the unborn father, he transfigured himself as he pleased, and thus ascended to him who had sent him, deriding them, inasmuch as he could not be laid hold of, and was invisible to all.-

— Against Heresies, Book I, Chapter 24, Section 40

Irenaeus mentions this view again:

He appeared on earth as a man and performed miracles. Thus he himself did not suffer. Rather, a certain Simon of Cyrene was compelled to carry his cross for him. It was he who was ignorantly and erroneously crucified, being transfigured by him, so that he might be thought to be Jesus. Moreover, Jesus assumed the form of Simon, and stood by laughing at them.[34][35] Irenaeus, Against Heresies.[36]

Another Gnostic writing, found in the Nag Hammadi library, Second Treatise of the Great Seth has a similar view of Jesus' death:

I was not afflicted at all, yet I did not die in solid reality but in what appears, in order that I not be put to shame by them

and also:

Another, their father, was the one who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I. Another was the one who lifted up the cross on his shoulder, who was Simon. Another was the one on whom they put the crown of thorns. But I was rejoicing in the height over all the riches of the archons and the offspring of their error and their conceit, and I was laughing at their ignorance

Coptic Apocalypse of Peter, likewise, reveals the same views of Jesus' death:

I saw him (Jesus) seemingly being seized by them. And I said 'What do I see, O Lord? That it is you yourself whom they take, and that you are grasping me? Or who is this one, glad and laughing on the tree? And is it another one whose feet and hands they are striking?' The Savior said to me, 'He whom you saw on the tree, glad and laughing, this is the living Jesus. But this one into whose hands and feet they drive the nails is his fleshly part, which is the substitute being put to shame, the one who came into being in his likeness. But look at him and me.' But I, when I had looked, said 'Lord, no one is looking at you. Let us flee this place.' But he said to me, 'I have told you, 'Leave the blind alone!'. And you, see how they do not know what they are saying. For the son of their glory instead of my servant, they have put to shame.' And I saw someone about to approach us resembling him, even him who was laughing on the tree. And he was with a Holy Spirit, and he is the Savior. And there was a great, ineffable light around them, and the multitude of ineffable and invisible angels blessing them. And when I looked at him, the one who gives praise was revealed.

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- Religions of the world Lewis M. Hopfe – 1979 "Some Muslims have suggested and practiced textual criticism of the Quran in a manner similar to that practiced by Christians and Jews on their bibles. No one has yet suggested the higher criticism of the Quran."

- LESTER, TOBY (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". Atlantic. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Egypt's culture wars: politics and practice – Page 278 Samia Mehrez – 2008 Middle East report: Issues 218–222; Issues 224–225 Middle East Research & Information Project, JSTOR (Organization) – 2001 Shahine filed to divorce Abu Zayd from his wife, on the grounds that Abu Zayd's textual criticism of the Quran made him an apostate, and hence unfit to marry a Muslim. Abu Zayd and his wife eventually relocated to the Netherlands

- Christian-Muslim relations: yesterday, today, tomorrow Munawar Ahmad Anees, Ziauddin Sardar, Syed Z. Abedin – 1991 For instance, a Christian critic engaging in textual criticism of the Quran from a biblical perspective will surely miss the essence of the quranic message. Just one example would clarify this point.

- Studies on Islam Merlin L. Swartz – 1981 One will find a more complete bibliographical review of the recent studies of the textual criticism of the Quran in the valuable article by Jeffery, "The Present Status of Qur'anic Studies," Report on Current Research on the Middle East

- Leirvik 2010, p. 33.

- Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34.

- Lester, Toby (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Coughlan, Sean (22 July 2015). "'Oldest' Koran fragments found in Birmingham University". BBC News. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "New Light on the History of the Qur'anic Text?". The Huffington Post.

- Quran 21:30

- Quran 21:31–33

- Campbell, Duncan (21 February 2006). "Academics fight rise of creationism at universities" – via www.theguardian.com.

- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2013/jan/11/muslim-thought-on-evolution-debate

- webmaster (6 December 2011). "Are evolution and religion compatible?". The Stream - Al Jazeera English.

- "Surah Al-'Ankabut [29:14]". Surah Al-'Ankabut [29:14].

- "Surah Hud [11:35-41]". Surah Hud [11:35-41].

- "Surah Al-A'raf [7:64]". Surah Al-A'raf [7:64].

- The Qur'an, Surah Ta Ha, Ayah 85

- Rubin, Uri. "Tradition in Transformation: the Ark of the Covenant and the Golden Calf in Biblical and Islamic Historiography," Oriens (Volume 36, 2001): 202.

- Bietenholz 1994, p. 122-123.

- Van Donzel & Schmidt 2010, p. 57 fn.3.

- Pinault 1992, p. 181 fn.71.

- Glassé & Smith 2003, p. 39.

- Wheeler 2013, p. 96.

- Ernst 2011, p. 133.

- Glassé & Smith 2003, p. 38.

- Cook 2005, p. 205-206.

- "Et gentibus ipsorum autem apparuisse eum in terra hominem, et virtutes perfecisse. Quapropter neque passsum eum, sed Simonem quendam Cyrenæum angariatum portasse crucem ejus pro eo: et hunc secundum ignorantiam et errorem crucifixum, transfiguratum ab eo, uti putaretur ipse esse Jesus: et ipsum autem Jesum Simonis accepisse formam, et stantem irrisisse eos." Book 1, Chapter 19

- Joel L. Kraemer Israel Oriental Studies XII BRILL 1992 ISBN 9789004095847 p. 41

- Lawson, Todd (1 March 2009). The Crucifixion and the Quran: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought. Oneworld Publications. p. 12. ISBN 1851686355.

- Eddy, Paul Rhodes and Gregory A. Boyd (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 172. ISBN 0801031141. ...if there is any fact of Jesus' life that has been established by a broad consensus, it is the fact of Jesus' crucifixion.

- Joel L. Kraemer Israel Oriental Studies XII BRILL 1992 ISBN 9789004095847 p. 41

- Haer. 1.24.4

- Kelhoffer, James A. (2014). Conceptions of "Gospel" and Legitimacy in Early Christianity. Mohr Siebeck. p. 80. ISBN 9783161526367.

- "Et gentibus ipsorum autem apparuisse eum in terra hominem, et virtutes perfecisse. Quapropter neque passsum eum, sed Simonem quendam Cyrenæum angariatum portasse crucem ejus pro eo: et hunc secundum ignorantiam et errorem crucifixum, transfiguratum ab eo, uti putaretur ipse esse Jesus: et ipsum autem Jesum Simonis accepisse formam, et stantem irrisisse eos." Book 1, Chapter 19

Bibliography

- Roslan Abdul-Rahim (December 2017). "Demythologizing the Qur'an Rethinking Revelation Through Naskh al-Qur'an" (PDF). Global Journal Al-Thaqafah (GJAT). 7 (2): 51–78. ISSN 2232-0474. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Bannister, Andrew G. "Retelling the Tale: A Computerised Oral-Formulaic Analysis of the Qur'an. Presented at the 2014 International Qur'an Studies Association Meeting in San Diego". academia.edu. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Burton, John (1990). The Sources of Islamic Law: Islamic Theories of Abrogation (PDF). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0108-2. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192853449.

- Crone, Patricia (1987). Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (PDF). Princeton University Press.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, Michael (1977). HAGARISM, THE MAKING OF THE ISLAMIC WORLD (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Dashti, `Ali (1994). Twenty Three Years: A Study of the Prophetic Career of Mohammad (PDF). Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Donner, Fred M. (2008). "The Quran in Recent Scholarship". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 29-50.

- Dundes, Alan (2003). Fables of the Ancients?: Folklore in the Qur'an. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Gibb, H.A.R. (1953) [1949]. Mohammedanism : An Historical Survey (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Guillaume, Alfred (1978) [1954]. Islam. Penguin books.

- Hawting, G.R. (2000). "16. John Wansbrough, Islam, and Monotheism". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 489–509.

- Holland, Tom (2012). In the Shadow of the Sword. UK: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53135-1. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Ibn Warraq, ed. (2000). "2. Origins of Islam: A Critical Look at the Sources". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. Prometheus. pp. 89–124.

- Ibn Warraq, ed. (2000). "1. Studies on Muhammad and the Rise of Islam". The Quest for the Historical Muhammad. Prometheus. pp. 15–88.</ref>

- Ibn Warraq (2002). Ibn Warraq (ed.). What the Koran Really Says : Language, Text & Commentary. Translated by Ibn Warraq. New York: Prometheus. pp. 23–106. ISBN 157392945X. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Ibn Warraq (1995). Why I Am Not a Muslim (PDF). Prometheus Books. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Leirvik, Oddbjørn (27 May 2010). Images of Jesus Christ in Islam (2nd ed.). New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2nd edition. pp. 33–66. ISBN 1441181601.

- Lippman, Thomas W. (1982). Understanding Islam : An Introduction to the Moslem World. New American Library.

- Lüling, Günter (1981). A Challenge to Islam for Reformation; Die Wiederentdeckung des Propheten Muhammad: eine Kritik am "christlichen" Abendland. Erlangen: Luling.</ref>

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said, ed. (2008). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2008). "Introduction, Quranic studies and its controversies". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 1-26.

- Donner, Fred M. (2008). "The Quran in Recent Scholarship". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 29-50.

- van Bladel, Kevin (2008). "The Alexander Legend in the Qur'an 18:83-102". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 175-203.

- Saadi, Abdul-Massih (2008). "Nascent Islam in the Seventh Century Syriac Sources". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 217-222.

- Böwering, Gerhard (2008). "Recent Research on the Construction of the Quran". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 70-87.

- Gillot, Claude (2008). "Reconsidering the Authorship of the Quran. Is the Quran party the fruit of a progressive and collective work?". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 88-108.

- Rodinson, Maxime (2002). Muhammad. London: Tauris Parke. ISBN 1-86064-827-4.

- Said, Edward (1978). Orientalism. Vintage. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Wansbrough, John (2004). QURANIC STUDIES : Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation (PDF). Foreword, Translations, and Expanded Notes by ANDREW RlPPIN. Amherst, New York: Prometheus. ISBN 1-59102-201-0. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Weiss, Bernard (April–June 1993). "Reviewed Work: The Sources of Islamic Law: Islamic Theories of Abrogation by John Burton". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 113 (2): 304–306. doi:10.2307/603054. JSTOR 603054.