William McGillivray

Lt.-Colonel The Hon. William McGillivray (1764 – October 16, 1825), of Chateau St. Antoine, Montreal, was a Scottish-born fur trader who succeeded his uncle as the last chief partner of the North West Company. He was elected a member of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada and afterwards was appointed to the Legislative Council of Lower Canada. In 1795, he was inducted as a member into the Beaver Club. During the War of 1812 he was given the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Corps of Canadian Voyageurs. He owned substantial estates in Scotland, Lower and Upper Canada. His home in Montreal was one of the early estates of the Golden Square Mile. McGillivray Ridge in British Columbia is named for him.[1]:168

William McGillivray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief Partner of the North West Company | |

| In office 1804–1821 | |

| Preceded by | Simon McTavish |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada | |

| In office 1808–1810 | |

| Preceded by | John Richardson |

| Succeeded by | Thomas McCord |

| Member of the Legislative Council of Lower Canada | |

| In office 1814–1825 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1764 Dunlichty, Inverness-shire |

| Died | 16 October 1825 (aged 60–61) St John's Wood, London |

| Spouse(s) | Susan married McGillivray Magdalen MacDonald of Garth |

| Children | 5 sons and 6 daughters |

| Residence | Chateau St.-Antoine, Golden Square Mile, Montreal |

Early years

In 1764, McGillivray was born at Dunlichity, near Daviot in the Scottish Highlands. He was the eldest son of Donald Roy McGillivray (1741–1803), tacksman of Achnalodan in Dunmaglass and later of Dalscoilt in Strathnairn. His mother, Anne (1740–1807), was the daughter of Lieutenant John McTavish (1701–1774), of Garthbeg.

The McGillivrays had traditionally held the Dunmaglass estate since the fourteenth century, and William's grandfather was a first cousin of the Chief of Clan McGillivray, Captain William McGillivray of Dunmaglass. However, on his side of the family the land had dissipated so that William's father was a small tenant on what had become part of the Lovat estate, and he was unable to provide secondary schooling for William and his brothers Duncan and Simon. When William's uncle, Simon McTavish, visited from Montreal in 1776, he paid for the education of the McGillivray boys and in 1784 brought William out to Canada to work for him in the North West Company, with an annual salary of £100.

Fur trading

As a clerk, after a year between Montreal and Rainy River, he was accompanied by proprietor Patrick Small to Île-à-la-Crosse, Saskatchewan. He spent the winter of 1786–87 at Snake Lake, setting up a trading post to compete with Gregory, McLeod & Co. He and Roderick McKenzie served their respective companies on good terms with each other. McGillivray played an important part in the two companies merging in 1787. The following year he returned to Île-à-la-Crosse and started trading at Rat River. This enabled him to purchase the share left open by Peter Pond in the North West Company, for £800 in 1790. Promoted to the rank of proprietor, he was given responsibility at Churchill River, where about 80 men and 40 Métis lived. At about this time he took his 'country wife'. In 1791, he was given charge of the westernmost department on the Athabasca River. All these postings were crucial to the experience he needed to one day step into his uncle's shoes, who was becoming increasingly dominant within the NWC.

McTavish, Frobisher & Co.

McGillivray returned to Montreal in 1793 and then took a trip to Scotland and England. He was now a partner in McTavish, Frobisher & Co., who controlled the NWC. With John Gregory, he was sent to manage the company's huge depot at Grand Portage, stirring jealousy among some of the other partners. When Joseph Frobisher retired in 1798, McGillivray took his place. He set up an agency at New York City to get around the East India Company's monopoly enabling them to trade with China. He was closely involved too with the firm of McTavish, Fraser & Co., at London, managed by another relation of his uncle's, John Fraser. In 1803, he helped organize the move of the NWC's main depot from Grand Portage to Thunder Bay. All this time he was dealing with relations with the Hudson's Bay Company and the splinter XY Company that had broken away from the NWC, led by John Richardson.

North West Company

When Simon McTavish died in 1804, McGillivray was well experienced and his choice to succeed him as the head of the NWC. He took over at a period of intense competition in the North American fur trade. His first action was to strike a deal ending the NWC's rivalry with the XY Company, later serving as a coalition between them. He surrendered 25% of the NWC's shares to the XY, but left his close friend, Alexander Mackenzie, out of the new co-partnership because of his reputation as a trouble-maker in the fur trade.

He reorganized the managing firm of McTavish, Frobisher and Co., which after John Gregory's retirement he renamed McTavish, McGillivrays and Co. The partners were himself, his brother Duncan, their brother-in-law Angus Shaw, and the two Hallowell brothers, James and William. The London firm of McTavish, Fraser & Co., remained unchanged except for McGillivray bringing in another brother, Simon. Due to rising costs within the NWC, he reduced manpower and curtailed the various costly habits of the living and travelling arrangements of the proprietors.

Competition with Astor

The rising costs and fall in profits were largely attributed to the intensified competition with John Jacob Astor and the HBC and the disruptions in the European market caused by the French Revolution. At first the NWC had collaborated with Astor, to avoid the East India Company's monopoly, and they shared some of the same trade routes to China. Over time, American pressure at their shared Pacific trading post on the mouth of the Columbia River was applied to the NWC in a subtle but systematic fashion, and to retain his freedom, McGillivray contemplated negotiating with the East India Company.

Hudson's Bay Company

The rivalry between the NWC of Montreal and the English-controlled HBC gradually degenerated into a bitter and violent struggle, first under McTavish and then McGillivray. From 1810, the scarcity of beaver began to be a problem and only served to heighten tensions between the two companies. The NWC was stronger on the ground, but it was not as financially strong as the HBC. During the War of 1812, the Americans destroyed the NWC's trading post at Sault Ste. Marie, giving them a net loss of over £8,000 for that year. Also in 1812, Lord Selkirk (a shareholder in the HBC) established the Red River Colony which directly served the interests of the HBC and affected the NWC's free transport of goods between Fort William and the fur-bearing Lake Athabasca region. Attempting to gain control over the movement of Pemmican in the region, Miles Macdonell, governor of the new Red River Colony, declared war with the established NWC men.

McGillivray had no illusions about Lord Selkirk's actions nor about the conduct of Miles Macdonell, remarking that Selkirk, "has thought proper lately to become the avowed rival of the North-West Company in the trade which they themselves have carried on for upwards of thirty years with credit to themselves. In a fair commercial competition, we have no objection to enter the lists with his Lordship, but we cannot remain passive spectators to the violence used to plunder or destroy our property".[2] The struggle was continued by Macdonell's successors, Robertson and then Semple, culminating in the Battle of Seven Oaks, in which Semple and some 20 settlers were killed by the NWC men, led by Cuthbert Grant.

Lord Selkirk arrested McGillivray and a number of NWC proprietors, holding them responsible. He seized Fort William and confiscated their furs for his own benefit. McGillivray was released and cleared at Montreal. The strength held by the NWC had been in a steady decline since 1810 and Selkirk's actions helped tip the balance in the power struggle towards the HBC, even with its debts. William's brother Simon conceded that from 1810 the richest and most talented partners of the NWC (notably those connected to the XY Company) had withdrawn and been replaced by men with less capital and less work ethic, and given to extravagant spending. Nepotism was also a problem: 14 members of the McTavish and McGillivray families (not including relatives by marriage) had been given partnerships since 1800, undermining the drive and morale of those hoping for promotion.

Eventually, William McGillivray accepted the inevitability of a merger between the NWC and the HBC, and his brother Simon McGillivray set about bringing it to pass. An agreement was signed in 1821 and the once great Montreal company disappeared under the trading banner of the HBC. McGillivray was content that he had settled on equal terms with the HBC, but only a few months after his death both McTavish, McGillivrays & Co., of London and McGillivrays, Thain & Co., of Montreal were declared bankrupt.

Life at Montreal

McGillivray enjoyed a leading role in Quebec society, particularly at Montreal. He had been elected a member of the Beaver Club in 1795 and in 1804 he was made a Justice of the Peace in the Indian Territories and for the Province of Quebec. In 1808, he replaced John Richardson in the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada and in 1814 he was elected to the Legislative Council of Lower Canada. He also became a significant landowner, purchasing 12,000 acres at Inverness, Quebec in 1802, which he later sold to Joseph Frobisher. During the War of 1812, McGillivray obtained the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Corps of Canadian Voyageurs, who succeeded in capturing Detroit. In gratitude for this service, the government of Upper Canada granted him the substantial lands at Plantagenet. In 1817, at a cost of £20,000, he purchased 'Bhein Ghael', a comparatively small but beautifully located Scottish estate on the Isle of Mull, overlooking Ghael Bay. In 1808, David Thompson had given what is now called the Kootenay River the name McGillivray's River, in honour of William and his brother Duncan.[3] After losing the NWC to the HBC, McGillivray had made ready to leave Montreal for a new life in England. He died during a trip to London in 1825 and was buried at St James's Church, Piccadilly, where there is a memorial to him and his wife in the church. Their graves were destroyed by enemy bombs during the Second World War.

Chateau Saint Antoine

McGillivray's home, Chateau St. Antoine, stood within 200 acres of parkland on Cote St. Antoine, roughly at the end of Dorchester Street. Built in 1803, the house enjoyed "a magnificent view of the city and river".[4] The McGillivrays were well known for their hospitality and kept open house at St. Antoine, as they had done before in their townhouse on St. Gabriel Street. Even his old rival John Jacob Astor came to dine there once a year on his annual trips to Montreal. The ballroom was said to be "an enchanting sight".[5] In 1820, the English geologist, John Jeremiah Bigsby, was invited to a dinner at St. Antoine, which he described at great length in his entertaining book, The Shoe and Canoe:

I had the pleasure of dining with the then great Amphictyon of Montreal at his seat, on a high terrace under the mountain, looking southwards and laid out in pleasure-grounds in the English style. The view from the drawing room windows of this large and beautiful mansion is extremely fine, too rich and fair, I foolishly thought, to be out of my native England. Close beneath you are scattered elegant country retreats embowered in plantations, succeeded by a crowd of orchards of delicious apples, spreading far to the right and left, and hedging in the glittering churches, hotels, and house-roofs of Montreal, Quebec...

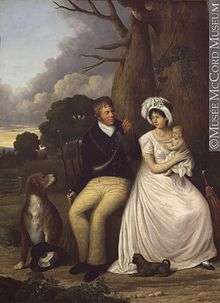

Mr McGillivray was accustomed to entertain the successive governors in their progresses, and was well entitled to such honour, not only from his princely fortune, but from his popularity, honesty of purpose, and intimate acquaintance with the true interests of the colony... My host was then a widower with two well-educated daughters. The company was various and consisted of a judge or two, some members of the Legislative Council and three or four retired partners of the North West Company of fur-traders (including David Thompson). Our dinner and wines were perfect. The conversation was fluent and sensible... It is hardly necessary to say that I passed a very agreeable evening. Our host was a large, handsome man, with the pleasant, successful look of the men of his habits and mode of life.[6]

Family

William McGillivray had four brothers and four sisters:

- Marjory Shaw née McGillivray (1766-1820), married Angus Shaw, childless

- Farquhar McGillivray (1769-?), never married and childless

- John McGillivray (1771-?), never married and childless

- Duncan McGillivray (~1772-1808), one son and one daughter

- Anne McTavish née McGillivray (~1773-1834), married Archibald McTavish, childless

- Elizabeth "Betsy" McGillivray (~1780-?), never married and childless

- Simon McGillivray (1783-1740), married Anne McGillivray née McTavish, two daughters

- Mary McGillivray (?-?), never married and childless

In the tradition of the fur traders, McGillivray had first taken a 'country wife' while in Manitoba, a Cree lady named Susan. They were the parents of three sons and a daughter, though one son did not survive to adulthood.

- Elizabeth Jourdain née McGillivray (1786–1858), married Daniel Jourdain, of Ste-Elizabeth de Joliette, Quebec, one daughter. She was provided for generously in his will.

- Simon McGillivray Jr. (1791–1840), married Therese McGillivray née Roy, five sons and five daughters. He became a partner in the North West Company shortly before their merger with the HBC in 1821. He inherited £2,000 from his father and half of his lands at Plantagenet, Upper Canada.

- Joseph McGillivray (1791–1832), married Françoise "Fanny" McGillivray née Boucher, three sons. He was the twin of his brother, Simon, and named for his godfather, Joseph Frobisher. He became a partner in the North West Company in 1813. He inherited £2,000 from his father and half of his lands at Plantagenet, Upper Canada.

- William McGillivray (1796-1832), two sons

- Peter McGillivray (?-?), never married and childless

In 1800, at St. Mary's, Marylebone in London, McGillivray married Magdalen (d.1811), daughter of Captain John McDonald of Garth, Perthshire, by his wife Magdalen, daughter of James Small. Sir Alexander Mackenzie described Mrs. Magdalen McGillivray as, "an agreeable, lively brunette of the most expressive countenance".[7] Mrs. McGillivray's brothers were John MacDonald of Garth and The Hon. Archibald Macdonald, and their sister, Helen, was married to General Sir Archibald Campbell, 1st Baronet, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in the First Anglo-Burmese War. Mrs. McGillivray's mother was a niece of Major-General John Small and Alexander Small, two of the first cousins of General John Robertson Reid. The McGillivrays were the parents of five daughters and one son, but only two of their daughters reached adulthood.

- Magdalen McGillivray (1801-1801), never married and childless

- Mary McGillivray (1803-1803), never married and childless

- Anna Maria Auldjo née McGillivray (1805–1856), married Thomas Richardson Auldjo (1808–1837), of Montreal, in 1826 in London, two daughters. Her husband was the son of The Hon. Alexander Auldjo by his wife Eweretta Jane Richardson, sister of The Hon. John Richardson of Montreal. Thomas' brother, John Auldjo, was the first Briton to climb Mont Blanc. They lived between her father's Scottish estate, Bhein Ghael, on the Isle of Mull and Noel House opposite Kensington Palace in London. She inherited £10,000 and half of her father's Scottish lands. He died at Naples, visiting his brother, and she at Noel House.

- Helen Elizabeth McGillivray (1806-1806), never married and childless

- Magdalen Julia Brackenbury née McGillivray (1808-1888), married Vice-Admiral William Congreve Cutliffe Brackenbury (1815-1868) in 1842, three sons and three daughters. She was the god-daughter of Sir Isaac Brock and Mrs. Alexander Henry. Her husband was the son of Sir John MacPherson Brackenbury (1778–1847), of Raithby Hall, Lincolnshire. He was British Consul at Cadiz, where they lived. She inherited £10,000 and half of her father's Scottish lands.[8]

- William McGillivray (1809-1810), never married and childless

References

- Akrigg, G.P.V.; Akrigg, Helen B. (1986), British Columbia Place Names (3rd, 1997 ed.), Vancouver: UBC Press, ISBN 0-7748-0636-2

- Northwest to the Sea; a biography of William McGillivray (Toronto and Vancouver, 1975).

- Nisbet, Jack (1994). Sources of the River: Tracking David Thompson Across Western North America. Sasquatch Books. pp. 130–131. ISBN 1-57061-522-5.

- Montreal in Evolution: Historical Analysis of the Development of Montreal's Architecture and Urban Environment. By Jean-Claude Marsan

- The Higher Hill (1944). By Grace MacLennan & Grant Campbell

- Page 113 onwards in 'The Shoe and Canoe; or pictures of travel in the Canadas' (published at London, 1850) by John Jeremiah Bigsby

- The Montreal Gazette - Nov 4, 1961 - McGillivray and Chateau St. Antoine

- Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 16.

- Ouellet, Fernand (1987). "McGillivray, William". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. VI (1821–1835) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- "Biography of William McGillivray". Dictionnaire des parlementaires du Québec de 1792 à nos jours (in French). National Assembly of Quebec.