Copán

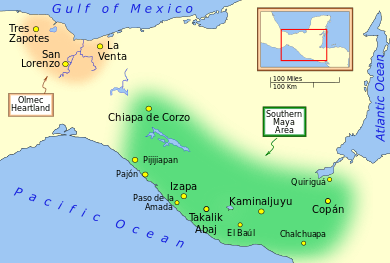

Copán is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization in the Copán Department of western Honduras, not far from the border with Guatemala. It was the capital city of a major Classic period kingdom from the 5th to 9th centuries AD. The city was in the extreme southeast of the Mesoamerican cultural region, on the frontier with the Isthmo-Colombian cultural region, and was almost surrounded by non-Maya peoples.

One of two simian sculptures on Temple 11,[1] possibly representing howler monkey gods. | |

Shown within Mesoamerica  Copán (Honduras) | |

| Location | Copán Ruinas, Copán Department, Honduras |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 14°50′15″N 89°08′33″W |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Preclassic to Postclassic |

| Cultures | Maya civilization |

| Site notes | |

| Criteria | Cultural: iv, vi |

| Reference | 129 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th session) |

| Area | 15.095 ha |

Copán was occupied for more than two thousand years, from the Early Preclassic period to the Postclassic. The city developed a distinctive sculptural style within the tradition of the lowland Maya, perhaps to emphasize the Maya ethnicity of the city's rulers.

The city has a historical record that spans the greater part of the Classic period and has been reconstructed in detail by archaeologists and epigraphers. Copán was a powerful city ruling a vast kingdom within the southern Maya area. The city suffered a major political disaster in AD 738 when Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil, one of the greatest kings in Copán's dynastic history, was captured and executed by his former vassal, the king of Quiriguá.[4] This unexpected defeat resulted in a 17-year hiatus at the city, during which time Copán may have been subject to Quiriguá in a reversal of fortunes.[5]

A significant portion of the eastern side of the acropolis was eroded away by the Copán River; the river has since been diverted to protect the site from further damage.

Names

It is thought likely that the ancient name of Copán was Oxwitik (pronounced [oʃwitik]), meaning the "Three Witiks", although the meaning of the word witik itself remains obscure.[6][7]

Location

Copán is in western Honduras close to the border with Guatemala. It lies within the municipality of Copán Ruinas in the department of Copán. It is in a fertile valley among foothills at 700 meters (2,300 ft) above mean sea level. The ruins of the site core of the city are 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) from the modern village of Copán Ruinas, which is built on the site of a major complex dating to the Classic period.[8]

In the Preclassic period the floor of the Copán Valley was undulating, swampy and prone to seasonal flooding. In the Early Classic, the inhabitants flattened the valley floor and undertook construction projects to protect the city's architecture from the effects of flooding.[9]

Copán had a major influence on regional centres across western and central Honduras, stimulating the introduction of Mesoamerican characteristics to local elites.[10]

Population

At the peak of its power in the Late Classic, the kingdom of Copán had a population of at least 20,000 and covered an area of over 250 square kilometers (100 sq mi).[11] The greater Copán area consisting of the populated areas of the valley covered about a quarter of the size of the city of Tikal. It is estimated that the peak population in central Copán was between 6000 and 9000 in an area of 0.6 square kilometers (0.23 sq mi), with a further 9,000 to 12,000 inhabitants occupying the periphery—an area of 23.4 square kilometers (9.0 sq mi). Additionally, there was an estimated rural population of 3,000 to 4,000 in a 476-square-kilometer (184 sq mi) area of the Copán Valley, giving an estimated total population of 18,000 to 25,000 people in the valley during the Late Classic period.

History

Little is known of the rulers of Copán before the founding of a new dynasty with its origins at Tikal in the early 5th century AD, although the city's origins can be traced back to the Preclassic period. After this, Copán became one of the more powerful Maya city states and was a regional power in the southern Maya region. However, it suffered a catastrophic defeat at the hands of its former vassal state Quirigua in 738, when the long-ruling king Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil was captured and beheaded by Quirigua's ruler K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat (Cauac Sky). Although this was a major setback, Copán's rulers began to build monumental structures again within a few decades.[5]

The area of Copán continued to be occupied after the last major ceremonial structures and royal monuments were erected, but the population declined in the 8th and 9th centuries from perhaps over 20,000 in the city to less than 5,000. This decrease in population took over four centuries to actually show signs of collapse, showing the stability of this site even after the fall of the ruling dynasties and royal families.[15] The ceremonial center was long abandoned and the surrounding valley home to only a few farming hamlets at the time of the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century.

Rulers

References to the predynastic rulers of Copán are found in later texts, but none of these texts predate the refounding of Copán in AD 426.

| Name (or nickname) | Ruled | Dynastic succession no. | Alternative names |

|---|---|---|---|

| K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' | 426 – c. 437 | 1 | Great-Sun First Quetzal Macaw |

| K'inich Popol Hol | c. 437 | 2 | Great-Sun |

| name unknown | c. 455 | 3 | Ruler 3 |

| Ku Ix | c. 465 | 4 | K'altuun Hix, Tuun K'ab' Hix |

| name unknown | c. 476 | 5 | Ruler 5 |

| Muyal Jol | c. 485 | 6 | Ruler 6 |

| B'alam Nehn | 504–544 | 7 | Jaguar Mirror; Waterlily-Jaguar |

| Wil Ohl K'inich | 532–551 | 8 | Ruler 8; Head on Earth |

| Sak-Lu | 551–553 | 9 | Ruler 9 |

| Tzi-B'alam | 553–578 | 10 | Moon Jaguar |

| K'ak' Chan Yopaat | 578–628 | 11 | B'utz' Chan; Smoke Serpent |

| Chan Imix K'awiil | 628–695 | 12 | Smoke Jaguar; Smoke Imix |

| Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil | 695–738 | 13 | 18 Rabbit |

| Ajaw K'ak' Joplaj Chan K'awiil | 738–749 | 14 | Smoke Monkey |

| Ajaw K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil | 749–763 | 15 | Smoke Shell; Smoke Squirrel |

| Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat | 763 – after 810 | 16 | Yax Pac |

| Ukit Took | 822 | 17? | – |

Predynastic history

The fertile Copán River valley was long a site of agriculture before the first known stone architecture was built in the region about the 9th century BC. The city was important before its refounding by a foreign elite; mentions of the predynastic history of Copán are found in later texts, but none of these predates the refounding of the city in AD 426. There is an inscription that refers to the year 321 BC, but no text explains the significance of this date.[20] An event at Copán is linked to another event that happened 208 days before in AD 159 at an unknown location that is also mentioned on a stela from Tikal, suggesting that it is a location somewhere in the Petén Basin, possibly the great Preclassic Maya city of El Mirador. This AD 159 date is mentioned in several texts and is linked to a figure known as "Foliated Ajaw". This same person is mentioned on the carved skull of a peccary recovered from Tomb 1, where he is said to perform an action with a stela in AD 376.[20]

K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and K'inich Popol Hol

The city was refounded by K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', establishing it as the capital of a new Maya kingdom. This coup was apparently organized and launched from Tikal. Texts record the arrival of a warrior named K'uk' Mo' Ajaw who was installed upon the throne of the city in AD 426 and given a new royal name, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and the ochk'in kaloomte "Lord of the West" title used a generation earlier by Siyaj K'ak', a general from the great metropolis of Teotihuacan who had decisively intervened in the politics of the central Petén. K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' was probably from Tikal and was likely to have been sponsored by Siyaj Chan K'awill II, the 16th ruler in the dynastic succession of Tikal. K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' may have legitimized his claim to rulership by marrying into the old Copán royal family, evidenced from the remains of his presumed widow. Bone analysis of her remains indicates that she was local to Copán.[23] After the establishment of the new kingdom of Copán, the city remained closely allied with Tikal. The hieroglyphic text on Copán Altar Q describes the lord being elevated to kingship with the receipt of his royal scepter. The ceremonies involved in the founding of the Copán dynasty also included the installation of a subordinate king at Quiriguá.[25]

A text from Tikal mentions K'uk' Mo' and has been dated to AD 406, 20 years before K'uk' Mo' Ajaw founded the new dynasty at Copán. Both names are likely to refer to the same individual originally from Tikal. Although none of the hieroglyphic texts that mention the founding of the new Copán dynasty describe how K'uk' Mo' arrived at the city, indirect evidence suggests that he conquered the city by military means. On Altar Q he is depicted as a Teotihuacano warrior with goggle eyes and a war serpent shield. When he arrived at Copán he initiated the construction of various structures, including one temple in the talud-tablero style typical of Teotihuacan and another with inset corners and apron moldings that are characteristic of Tikal. These strong links with both the Maya and Central Mexican cultures suggest that he was at least a Mexicanized Maya or possibly even from Teotihuacan.[20] The dynasty founded by king K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' ruled the city for four centuries and included sixteen kings plus a probable pretender who would have been seventeenth in line. Several monuments have survived that were dedicated by K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and by his heir.

K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' died between AD 435 and AD 437. In 1995 a tomb underneath the talud-tablero Hunal temple was discovered by a team of archaeologists led by Robert Sharer and David Sedat. The tomb contained the skeleton of an elderly man with rich offerings and evidence of battle wounds. The remains have been identified as those of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' due to their location underneath a sequence of seven buildings erected in his honor. Bone analysis has identified the remains as being those of someone foreign to Copán.[20]

K'inich Popol Hol inherited the throne of Copán from K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', who was his father. He undertook major construction projects with the redesign of the core of Copán. Popol Hol is not the original name of this king but rather a nickname based on the appearance of his Teotihuacan-linked name glyph.[29] K'inich Popol Hol oversaw the construction of the first version of the Mesoamerican ballcourt at the city, which was decorated with images of the scarlet macaw, a bird that features prominently in Maya mythology. His greatest construction activity was in the area of his father's palace, now underlying Structure 10L-16, which he demolished after entombing his father there. He then built three successive buildings on top of the tomb in rapid succession.[30]

Other early dynastic rulers

Very little is known about Rulers 3 to 6 in the dynastic succession, although it is known from a fragment of a broken monument reused as construction fill in a later building that one of them was a son of Popol Hol. Ruler 3 is depicted on the 8th-century Altar Q, but his name glyph has broken away. Ku Ix was the 4th ruler in the succession. He rebuilt temple 10L-26 in the Acropolis, erecting a stela there and a hieroglyphic step at its base. Although this king is also mentioned on a few other fragments of sculpture, no dates accompany his name. The next two kings in the dynastic sequence are only known from their sculptures on Altar Q.[31]

B'alam Nehn (often referred to as Waterlily Jaguar) was the first king to actually record his position in the dynastic succession, declaring that he was seventh in line from K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'. Stela 15 records that he was already ruling Copán by AD 504. B'alam Nehn is the only king of Copán to be mentioned in a hieroglyphic text from outside of the southeastern Maya region. His name appears in a text on Stela 16 from Caracol, a site in Belize. The stela dates to AD 534, but the text is not well understood. B'alam Nehn undertook major construction projects in the Acropolis, building over an early palace with a number of important structures.[32]

Wil Ohl K'inich, the eighth ruler, is another king known only by his appearance on Altar Q.[32] He was succeeded by Ruler 9 in AD 551, his accession being described on the Hieroglyphic Stairway. He is also depicted on Altar Q even though he ruled for less than two years.[33]

|

| Maya civilization |

|---|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

The 10th ruler is nicknamed Moon Jaguar by Mayanists. He was a son of B'alam Nehn, the 7th ruler. He was enthroned in May 553. His surviving monuments were found in the modern village of Copán Ruinas, which was a major complex during the Classic period. The most famous construction dating to his reign is the elaborate Rosalila phase of Temple 16, discovered entombed intact under later phases of the temple during archaeological tunneling work.[34]

K'ak' Chan Yopaat and Smoke Imix

K'ak' Chan Yopaat was the eleventh dynastic ruler at Copán. He was crowned as king in AD 578, 24 days after the death of Moon Jaguar. At the time of his rule, Copán was undergoing an unprecedented rise in population, with residential land use spreading to all available land in the entire Copán Valley. The two surviving stelae of K'ak' Chan Yopaat contain long, hard-to-decipher hieroglyphic texts and are the oldest monuments at the site to survive without being either broken or buried. He reigned for 49 years until his death on 5 February 628. His name is recorded on four stelae erected by his successors, one of which describes a rite performed with relics from his tomb in AD 730, almost a hundred years after his death.[35]

Smoke Imix was crowned 16 days after the death of K'ak' Chan Yopaat. He is thought to have been the longest reigning king of Copán, ruling from 628 to 695. He is believed to have been born in AD 612 and to have become king at the age of 15. Archaeologists have recovered little evidence of activity for the first 26 years of his reign, but in AD 652 there was a sudden explosion of monument production, with two stelae being erected in the Great Plaza and a further four in important locations across the Copán Valley. These monuments all celebrated a k'atun-ending. He also erected a stela at the Santa Rita site 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) away and is mentioned on Altar L at Quiriguá in relation to the same event in 652. It is thought that he was trying to stamp his authority throughout the whole valley after the end of some earlier restriction to his freedom to rule as he wished.[36]

After this sudden spate of activity, Smoke Imix continued to rule until almost the end of the 7th century; he dedicated another nine known monuments and made important changes to the architecture of Copán, including the construction of Structure 2, which closes the northern side of the Great Plaza, and a new version of Temple 26, nicknamed Chorcha. Smoke Imix ruled Copán for 67 years and died on 15 June 695 at the age of 79, an age that was so distinguished that it is used to identify him in place of his name on Altar Q. His tomb had already been prepared in the Chorcha phase of Temple 26 and he was buried just two days after his death.[37]

Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil

.jpg)

Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil was crowned as the 13th king in the Copán dynasty in July 695. He oversaw both the apogee of Copán's achievements and also one of the city's most catastrophic political disasters. During his reign, the sculptural style of the city evolved into the full in-the-round sculpture characteristic of Copán. In AD 718, Copán attacked and defeated the unidentified site of Xkuy, recording its burning on an unusual stone cylinder. In AD 724 Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil installed K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat as a vassal on the throne of Quiriguá. Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil was confident enough in his power to rank his city among the four most powerful states in the Maya region, together with Tikal, Calakmul and Palenque, as recorded on Stela A. In contrast to his predecessor, Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil concentrated his monuments in the site core of the Copán; his first was Stela J, dated to AD 702 and erected at the eastern entrance to the city.[17]

He continued to erect a further seven high-quality stelae until AD 736, monuments that are considered masterpieces of Classic Maya sculpture with such mastery of detail that they represent the highest pinnacle of Maya artistic achievement.[38] The stelae depict king Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil ritually posed and bearing the attributes of a variety of deities, including B'olon K'awiil, K'uy Nik Ajaw and Mo' Witz Ajaw.[17] The king also carried out major construction works, including a new version of Temple 26 that now bore the first version of the Hieroglyphic Stairway, plus two temples that have now been lost to the erosion of the Copán River. He also encased the Rosalila phase of Temple 16 within a new phase of construction. He remodelled the ballcourt, then demolished it and built a new one in its place.[39]

Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil had only recently dedicated the new ballcourt in AD 738 when a completely unexpected disaster befell the city. Twelve years earlier he had installed K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat on the throne of Quiriguá as his vassal.[40] By 734 the king of Quiriguá had shown he was no longer an obedient subordinate when he began to refer to himself as k'ul ajaw, "holy lord", rather than simply as a subordinate lord ajaw.[41] K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat appears to have taken advantage of wider political rivalries and allied himself with Calakmul, the sworn enemy of Tikal. Copán was firmly allied with Tikal and Calakmul used its alliance with Quiriguá to undermine Tikal's key ally in the south.[42]

Although the exact details are unknown, in April 738 K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat captured Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil and burned two of Copán's patron deities. Six days later Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil was decapitated in Quiriguá.[43] This coup does not seem to have physically affected either Copán or Quiriguá; there is no evidence that either city was attacked at this time and the victor seems not to have received any detectable tribute.[44] All of this seems to imply that K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat managed to somehow ambush Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil, rather than to have defeated him in outright battle. It has been suggested that Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil was attempting to attack another site to secure captives for sacrifice in order to dedicate the new ballcourt when he was ambushed by K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat and his Quiriguá warriors.[45]

In the Late Classic, alliance with Calakmul was frequently associated with the promise of military support. The fact that Copán, a much more powerful city than Quiriguá, failed to retaliate against its former vassal implies that it feared the military intervention of Calakmul. Calakmul was far enough away from Quiriguá that K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat was not afraid of falling directly under its power as a full vassal state, even though it is likely that Calakmul sent warriors to help in the defeat of Copán. The alliance instead seems to have been one of mutual advantage: Calakmul managed to weaken a powerful ally of Tikal while Quiriguá gained its independence.[46] The disaster for Copán had long-lasting consequences; major construction ceased and no new monuments were raised for the next 17 years.[47]

Later rulers

K'ak' Joplaj Chan K'awiil was installed as the 14th dynastic ruler of Copán on 7 June 738, 39 days after the execution of Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil. Little is known of his reign due to the lack of monuments raised after Quiriguá's surprise victory. Copán's defeat had wider implications due to the fracturing of the city's domain and the loss of the key Motagua River trade route to Quiriguá. The fall in Copán's income and corresponding increase at Quiriguá is evident from the massive commissioning of new monuments and architecture at the latter city, and Copán may even have been subject to its former vassal. K'ak' Joplaj Chan K'awiil died in January 749.[5]

The next ruler was K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil, a son of K'ak' Joplaj Chan K'awiil. The early period of his rulership fell within Copán's hiatus, but later on he began a programme of renewal in an effort to recover from the city's earlier disaster. He built a new version of Temple 26, with the Hieroglyphic Stairway being reinstalled on the new stairway and doubled in length. Five life-size statues of seated rulers were installed seated upon the stairway. K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil died in the early 760s and is likely to have been interred in Temple 11, although the tomb has not yet been excavated.[49]

Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat was the next ruler, 16th in the dynasty founded by K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', although he appears not to have been a direct descendant of his predecessor. He took the throne in June 763 and may have been only 9 years old.[1] He produced no monumental stelae and instead dedicated hieroglyphic texts incorporated into the city's architecture and smaller altars. Texts make an obscure reference to his father but his mother was a noblewoman from distant Palenque in Mexico. He built the platform of Temple 11 over the tomb of the previous king in AD 769 and added a two-storey superstructure that was finished in AD 773.[1] Around AD 776, he completed the final version of Temple 16 over the tomb of the founder. At the base of the temple, he placed the famous Altar Q, which shows each of the 16 rulers of the city from K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' through to Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, with a hieroglyphic text on top describing the founding of the dynasty.[50] By the latter 8th century, the nobility had become more powerful, raising palaces with hieroglyphic benches that were as richly constructed as those of the king. At the same time, local satellites were displaying their own local power, as demonstrated by the ruler of Los Higos erecting his own stela in AD 781.[50] Towards the end of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat's reign, the city of Copán was struggling with overpopulation and a lack of local resources, with a distinct fall in living standards among the populace.[50] Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat was able to celebrate his second K'atun in AD 802 with his own monument, but the king's participation in the K'atun ending ceremony of AD 810 was marked at Quiriguá, not at Copán.[50] By this time the city's population was over 20,000 and it had long needed to import basic necessities from outside.[51]

The troubled times enveloping Copán at this time are evident from the funerary tomb of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, which bears sculptures of the king performing war dances with spear and shield in hand. The sculpted column from the temple shrine has a hieroglyphic text reading "toppling of the Foundation House" that may refer to the fall of the Copán dynasty.[52] Shortage and disease afflicted the massively overpopulated valley of Copán when its last known king, Ukit Took', came to the throne on 6 February 822. He commissioned Altar L in the style of Altar Q but the monument was never finished — one face shows the enthronement of the king and a second face was started but two others were completely blank. The long line of kings at the once great city had come to an end. Before the end, even the nobility had been struck by disease, perhaps because epidemics among the malnourished masses spread to the elite. With the end of political authority at the city the population collapsed to a fraction of what it had been at its height.[52] This collapse of the city-state, which people believe occurred sometime between 800 and 830 AD, was sudden. However, the population continued to persist and even flourish between the years 750 and 900 AD, and then gradually declined soon thereafter.[53] In the Postclassic period the valley was occupied by villagers who stole the stone from the monumental architecture of the city in order to build their simple house platforms.[52]

Modern history

The first post-Spanish conquest mention of Copán was in an early colonial period letter dated 8 March 1576. The letter was written by Diego García de Palacio, a member of the Royal Audience of Guatemala, to king Philip II of Spain.[54] French explorer Jean-Frédéric Waldeck visited the site in the early 19th century and spent a month there drawing the ruins.[55] Colonel Juan Galindo led an expedition to the ruins in 1834 on behalf of the government of Guatemala and wrote articles about the site for English, French and North American publications.[55] John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood visited Copán and included a description, map and detailed drawings in Stephens' Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán, published in 1841.[55] The site was later visited by British archaeologist Alfred Maudslay.[55] Several expeditions sponsored by the Peabody Museum of Harvard University worked at Copán during the late 19th and early 20th centuries,[56] including the 1892–1893 excavation of the Hieroglyphic Stairway by John G. Owens and George Byron Gordon.[57] The Carnegie Institution also sponsored work at the site in conjunction with the government of Honduras.[58]

The Copán buildings suffered significantly from forces of nature in the centuries between the site's abandonment and the rediscovery of the ruins. After the abandonment of the city the Copán River gradually changed course, with a meander destroying the eastern portion of the acropolis (revealing in the process its archaeological stratigraphy in a large vertical cut) and apparently washing away various subsidiary architectural groups, including at least one courtyard and 10 buildings from Group 10L–2.[59] The cut is an important archaeological feature at the site, with the natural erosion having created an enormous cross-section of the acropolis. This erosion cut away a large portion of the eastern part of the acropolis and revealed a vertical cross-section that measures 37 meters (121 ft) high at its tallest point and 300 meters (980 ft) long. Several buildings recorded in the 19th century were destroyed, plus an unknown amount of the acropolis that was eroded before it could be recorded. In order to avoid further destruction of the acropolis, the Carnegie Institution redirected the river to save the archaeological site, diverting it southwards in the 1930s; the dry former riverbed was finally filled in at the same time as consolidation of the cut in 1990s. Structures 10L–19, 20, 20A and 21 were all destroyed by the Copán River as it eroded the site away, but had been recorded by investigators in the 19th century.

Copán was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980, and UNESCO approved funding of US$95,825 between 1982 and 1999 for various works at the site.[61] Looting remains a serious threat to Copán. A tomb was looted in 1998 as it was being excavated by archaeologists.[62]

Site description

The Copán site is known for a series of portrait stelae, most of which were placed along processional ways in the central plaza of the city and the adjoining acropolis, a large complex of overlapping step-pyramids, plazas, and palaces. The site has a large court for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame.[63]

The site is divided into various groups, with the Main Group and the Cemetery Group in the site core linked by a sacbe to the Sepulturas Group to the northeast. Central Copán had a density of 1449 structures per square kilometer (3,750/sq mi), while in greater Copán as a whole this density fell to 143 per square kilometre (370/sq mi) over a surveyed area of 24.6 square kilometers (9.5 sq mi).

Main Group

The Main Group represents the core of the ancient city and covers an area of 600 by 300 meters (1,970 ft × 980 ft). The main features are the Acropolis, which is a raised royal complex on the south side, and a group of smaller structures and linked plazas to the north, including the Hieroglyphic Stairway and the ballcourt. The Monument Plaza contains the greatest concentration of sculpted monuments at the site.

The Acropolis was the royal complex at the heart of Copán. It consists of two plazas that have been named the West Court and the East Court. They are both enclosed by elevated structures. Archaeologists have excavated extensive tunnels under the Acropolis, revealing how the royal complex at the heart of Copán developed over the centuries and uncovering several hieroglyphic texts that date back to the Early Classic and verify details of the early dynastic rulers of the city who were recorded on Altar Q hundreds of years later. The deepest of these tunnels have revealed that the first monumental structures underlying the Acropolis date archaeologically to the early 5th century AD, when K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' established the royal dynasty. These early buildings were built of stone and adobe and were themselves built upon earlier earth and cobble structures dating to the predynastic period. The two styles of building overlap somewhat, with some of the earthen structures being expanded during the first hundred years or so of the dynastic history of the city. The early dynastic masonry buildings of the Acropolis included several with the Early Classic apron-molding style of Tikal and one built in the talud-tablero style associated with Teotihuacan, although at the time the talud-tablero form was in use at both Tikal and Kaminaljuyu as well as in Central Mexico.

Structure 10L-4 is a platform with four stairways situated by the Monument Plaza.

.jpg)

Structure 10L-11 is on the west side of the Acropolis. It encloses the south side of the Court of the Hieroglyphic Stairway and is accessed from it by a wide monumental stairway. This structure appears to have been the royal palace of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, the 16th ruler in the dynastic succession and the last known king of Copán. Structure 10L-11 was built on top of several earlier structures, one of which probably contains the tomb of his predecessor K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil. A small tunnel descends into the interior of the structure, possibly to the tomb, but it has not yet been excavated by archaeologists.[70] Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat built a new temple platform over his predecessor's tomb in AD 769. On top of this he placed a two-storey superstructure with a sculpted roof depicting the mythological cosmos. At each of its northern corners was a large sculpted Pawatun (a group of deities that supported the heavens). This superstructure had four doorways with panels of hieroglyphs sculpted directly onto the walls of the building. A bench inside the structure, removed by Maudslay in the nineteenth century and now in the British Museum's collection, once depicted the king's accession to the throne, overseen by deities and ancestors.[1][71]

| Phase | King | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Hunal | K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' | early 5th century AD |

| Yehnal | K'inich Popol Hol | mid-5th century AD |

| Margarita | K'inich Popol Hol | mid-5th century AD |

| Rosalila | Moon Jaguar | mid-6th century AD |

| Purpura | Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil | early 7th century AD |

_sm_(4289308339).jpg)

Structure 10L-16 (Temple 16) is a temple pyramid that is the highest part of the Acropolis. It is located between the East and West Courts at the heart of the ancient city.[72] The temple faces the West Court within the Acropolis and is dedicated to K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', the dynastic founder. The temple was placed on top of the original palace and tomb of the king. It is the final version of a number of temples built on top of each other, as was common practice in Mesoamerica. The earliest version of this temple is nicknamed Hunal; it was built in the talud-tablero style of architecture that was typical of Teotihuacan, with traces of brightly colored murals on the surviving traces of the interior walls. The king was buried in a vaulted crypt that was cut into the floor of the Hunal phase of the building, accompanied by rich offerings of jade. K'inich Popol Hol, son of the founder, demolished the palace of his father and built a platform on top of his tomb, named Yehnal by archaeologists. It was built in a distinctively Petén Maya style and bore large masks of K'inich Tajal Wayib', the sun god, which were painted red. This platform was encased within another much larger platform within a decade of its construction. This larger platform has been named Margarita and had stucco panels flanking its access stairway that bore entwined images of quetzals and macaws, which both form a part of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo's name. The Margarita phase contained a tomb with the richly accompanied burial of an elderly woman nicknamed the "Lady in Red". It is likely that she was the widow of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and the mother of K'inich Popol Hol. The upper chamber of the Margarita phase temple was converted to receive offerings and the unusual Xukpi stone, a dedicatory monument used in one of the earlier phases, was reused in this later phase.[74]

One of the best preserved phases of Temple 16 is the Rosalila, built over the remains of five previous versions of the temple. Archaeologist Ricardo Agurcia discovered the almost intact shrine while tunneling underneath the final version of the temple. Rosalila is notable for its excellent state of preservation, including the entire building from the base platform up to the roof comb, including its highly elaborate painted stucco decoration. Rosalila features K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' placed at the centre of a mythological tableau, combining the founder of the dynasty with the sky deity Itzamna in avian form. The mythological imagery also includes anthropomorphic mountains, skeletons and crocodiles. Vents in the exterior were designed so smoke from incense being burned inside the shrine would interact with the stucco sculpture of the exterior. The temple had a hieroglyphic stone step with a dedicatory inscription. The stone step is less well preserved than the rest of the building, but a date in AD 571 has been deciphered. Due to the deforestation of the Copán valley, the Rosalila building was the last structure at the site to use such elaborate stucco decoration — vast quantities of firewood could no longer be spared to reduce limestone to plaster. A life-size copy of the Rosalila building has been built at the Copán site museum.[34]

Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil encased the Rosalila phase under a new version of the building in the early 8th century AD. An offering was made as part of the rites to terminate the old phase and included a collection of eccentric flints worked into the profiles of humans and gods, which were wrapped in blue-dyed textiles.[76]

Structure 10L-18 is on the southeastern side of the Acropolis and has been damaged by the erosion caused by the Copán River, having lost its eastern side. Stairs on the south side of the structure lead down to a vaulted tomb that was looted in ancient times and was probably that of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. It was apparently plundered soon after the collapse of the Copán kingdom. Unusually for Copán, the summit shrine had four sculpted panels depicting the king performing war dances with spear and shield, emphasizing the rising tensions as the dynasty came to its end.[52]

Temples 10L-20 and 10L-21 were probably both built by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil. They were lost to the Copán River in the early 20th century.[76]

Structure 10L-22 is a large building on the north side of the East Court, in the Acropolis, and faces onto it. It dates to the reign of Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil and is the best preserved of the buildings from his rule. The superstructure of the building has an interior doorway with an elaborate sculpted frame and decorated with masks of the mountain god Witz. The outer doorway is framed by the giant mask of a deity, and has stylistic similarities with the Chenes regional style of distant Yucatán.[77] The temple was built to celebrate the completion of the king's first K'atun in power, in AD 715, and has a hieroglyphic step with a first-person phrase "I completed my K'atun". The building symbolically represents the mountain where maize was created.[39]

Structure 10L-25 is in the East Court of the Acropolis. It covers a rich royal tomb nicknamed Sub-Jaguar by archaeologists. It is presumed to be the tomb of either Ruler 7 (B'alam Nehn), Ruler 8 or Ruler 9, who all ruled in the first half of the 6th century AD.[78]

| Phase | King | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Yax | K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' | early 5th century AD |

| Motmot | K'inich Popol Hol | mid-5th century AD |

| Papagayo | Ku Ix | mid-5th century AD |

| Mascarón | Smoke Imix | 7th century AD |

| Chorcha | Smoke Imix | 7th century AD |

| Esmeralda | Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil | early 8th century AD |

| N/A | K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil | mid-8th century AD |

Structure 10L-26 is a temple that projects northwards from the Acropolis and is immediately to the north of Structure 10L-22. The structure was built by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil and K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil, the 13th and 15th rulers in the dynastic succession. The 10-meter (33 ft) wide Hieroglyphic Stairway ascends the building on the west side from the courtyard below. The earliest version of the temple, nicknamed Yax, was built during the reign of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', the dynastic founder, and has architectural features (such as inset corners) that are characteristic of Tikal and the central Petén region.[20] The next phase of the building was built by Yax K'uk' Mo's son K'inich Popol Hol and is nicknamed Motmot. This phase of the structure was more elaborate and was decorated with stucco. Set under the building was the Motmot capstone, covering a tomb with the unusual Teotihuacan-style burial of a woman, accompanied by a wide variety of offerings that included animal bones, mercury, jade and quartz, along with three severed human heads, all of which were male.[29] Ku Ix built a new phase of the building over Motmot, nicknamed Papagayo.[31]

Smoke Imix demolished the Papagayo phase and ritually interred the broken remains of its sculpted monuments, accompanied by stone macaw heads from an early version of the ballcourt. He then built a pyramid over the earlier phases, nicknamed Mascarón by archaeologists. It in turn was developed into the Chorcha pyramid with the addition of a long superstructure with seven doorways at the front and back. Before a new building was built over the top, the upper sanctuary was demolished and a tomb was inserted into the floor and covered with 11 large stone slabs. The tomb contained the remains of an adult male and a sacrificed child. The adult's badly decayed skeleton was wrapped in a mat and accompanied by offerings of fine jade, including ear ornaments and a necklace of sculpted figurines. The burial was accompanied by offerings of 44 ceramic vessels, jaguar pelts, spondylus shells, 10 paintpots and one or more hieroglyphic books, now decayed. There were also 12 ceramic incense burners with lids modeled into human figurines, thought to represent Smoke Imix and his 11 dynastic predecessors. The Chorcha building was dedicated to the long-lived 7th-century king Smoke Imix and it is therefore likely that the remains interred in the building are his.[21] Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil had sealed the Chorcha phase under a new version of the temple, nicknamed Esmeralda, by AD 710. The new phase bore the first version of the Hieroglyphic Stairway, which contains a lengthy dynastic history.[76] K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil built over the Esmeralda phase in the mid-8th century. He removed the Hieroglyphic Stairway from the earlier building and reinstalled it into his own version, while doubling the length of its text and adding five life-size statues of rulers dressed in the garb of Teotihuacano warriors, each seated on a step of the stairway. At the base of the stairway, he also raised Stela M, with his own image. The summit shrine of the temple bore a hieroglyphic text composed of full-figure hieroglyphs, each placed beside a similar glyph in faux-Mexican style, giving the appearance of a bilingual text.[49]

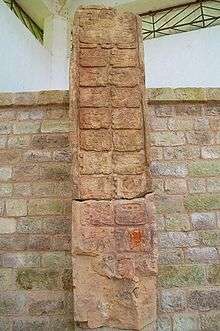

The Hieroglyphic Stairway climbs the west side of Structure 10L-26. It is 10 meters (33 ft) wide and has a total of 62 steps. Stela M and its associated altar are at its base and a large sculpted figure is located in the centre of every 12th step. These figures are believed to represent the most important rulers in the dynastic history of the site. The stairway takes its name from the 2200 glyphs that together form the longest known Maya hieroglyphic text. The text is still being reconstructed, having been scrambled by the collapse of the glyphic blocks when the façade of the temple collapsed.[79] The staircase measures 21 meters (69 ft) long and was first built by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in AD 710, being reinstalled and expanded in the following phase of the temple by K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil in AD 755.[48]

The Ballcourt is immediately north of the Court of the Hieroglyphic Stairway and is to the south of the Monument Plaza. It was remodeled by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil, who then demolished it and built a third version, which was one of the largest from the Classic period. It was dedicated to the great macaw deity and the buildings flanking the playing area carried 16 mosaic sculptures of the birds. The completion date of the ballcourt is inscribed with a hieroglyphic text upon the sloping playing area and is given as 6 January 738.[63]

The Monument Plaza or Great Plaza is on the north side of the Main Group.

Sepulturas Group

The Sepulturas Group is linked by a sacbe or causeway that runs southwest to the Monument Plaza in the Main Group. The Sepulturas Group consists of a number of restored structures, mostly elite residences that feature stone benches, some of which have carved decorations, and a number of tombs.

The group has a very long occupational history, with one house having been dated as far back as the Early Preclassic. By the Middle Preclassic, large platforms were being built from cobbles and several rich burials were made. By AD 800, the complex consisted of about 50 buildings arranged around 7 major courtyards.[51] At this time, the most important building was the House of the Bakabs, the palace of a powerful nobleman from the time of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. The building has a high-quality sculpted exterior and a carved hieroglyphic bench inside. A portion of the group was a subdistrict occupied by non-Maya inhabitants from Central Honduras who were involved in the trade network that brought in goods from that region.[51]

Other groups

The North Group is a Late Classic compound. Archaeologists have excavated fallen façades that bear hieroglyphic inscriptions and sculpted decoration.

The Cemetery Group is immediately south of the Main Group and includes a number of small structures and plazas.

Monuments

Altar Q is the most famous monument at Copán.[81] It was dedicated by king Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat in AD 776 and has each of the first 16 kings of the Copán dynasty carved around its side. Each figure is depicted seated on his name glyph. A hieroglyphic text is inscribed on the upper surface, relating the founding of the dynasty in AD 426–427. On one side, it shows the dynastic founder K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' transferring power to Yax Pasaj.[82] Tatiana Proskouriakoff first discovered the inscription on the West Side of Altar Q that tells us the date of the inauguration of Yax Pasaj. This portrayal of political succession tells us much about Early Classic Maya culture.

The Motmot Capstone is an inscribed stone that was placed over a tomb under Structure 10L-26. Its face was finely sculpted with portraits of the first two kings of the Copán dynasty, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and K'inich Popol Hol, facing towards each other with a double column of hieroglyphs between them, all contained within a quatrefoil frame. The frame and the hieroglyphic names of mythological locations underneath the feet of the two kings place them in a supernatural realm. The capstone bears two calendrical dates, in AD 435 and AD 441. The second of these is probably the date that the capstone was dedicated.[29]

The Xukpi Stone is a dedicatory monument from one of the earlier phases of the 10L-16 temple constructed to honor K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'. It bears the date of AD 437 and the names both K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' and K'inich Popol Hol, together with a possible mention of the Teotihuacan general Siyaj K'ak'. The monument has not been completely deciphered and its style and phrasing are unusual.[31] Originally it was used as a sculpted bench or step and the date on the monument is associated with the dedication of a funerary temple or a tomb, probably the tomb of K'inich' Yax K'uk' Mo', which was discovered underneath the same structure.

Stela 2 was erected in the Great Plaza by Smoke Imix in AD 652.[36]

Stela 3 is another stela erected by Smoke Imix in the Great Plaza in AD 652.[36]

Stela 4 was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in the early 8th century AD.[17]

Stela 7 dates to the reign of K'ak' Chan Yopaat, and was erected to celebrate the K'atun-ending ceremony of AD 613. It was found in the western complex now underneath the modern village of Copán Ruinas. It bears a long hieroglyphic text that has been only partially deciphered.[80]

Stela 9 was found in the modern village of Copán Ruinas, where it had been erected on the site of a major Classic period complex 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) outside of the site core. It was dedicated by Moon Jaguar and dates to AD 564.[8]

Stela 10 was erected outside of the site core by Smoke Imix in AD 652.[36]

Stela 11 was originally an interior column from Temple 18, the funerary shrine of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. When it was found, it was broken in two parts at the base of the temple. It portrays the king as the elderly Maya maize god and has imagery that seems to deliberately parallel the tomb lid of the Palenque king K'inich Janaab' Pakal, probably because of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat's close family ties to that city. The text of the column formed part of a longer text carved onto the interior walls of the temple and may describe the downfall of the Copán dynasty.[52]

Stela 12 was erected outside of the site core by Smoke Imix in AD 652.[36]

Stela 13 was erected outside the site core by Smoke Imix in AD 652.[36]

Stela 15 is dated to AD 524, during the reign of B'alam Nehn. Its sculpture consists entirely of hieroglyphic text, which mentions that king B'alam Nehn was ruling the city by AD 504.[32]

Stela 17 dates to AD 554, during the reign of Moon Jaguar. It originally stood in the nearby village of Copán Ruinas, which was a major complex in the Classic period.[8]

Stela 18 is a fragment of a monument bearing the name of K'inich Popol Hol. It was erected in the inner chamber of the 10L-26 temple.[83]

Stela 19 is a monument erected outside of the site core by Smoke Imix in AD 652.[36]

Stela 63 was dedicated by K'inich Popol Hol. Its sculpture consists purely of finely carved hieroglyphic texts and it is possible that it was originally commissioned by K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' with additional texts added to the sides of the monument by his son. The text contains the same date in AD 435 that appears on the Motmot Capstone. Stela 63 was deliberately broken, together with its hieroglyphic step, during the ritual demolishing of the Papagayo phase of Temple 26. The remains of the monuments were then interred in the building before the next phase was built.[84]

Stela A was erected in 731 by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil. It places his rulership among the four most powerful kingdoms in the Maya region, alongside Palenque, Tikal and Calakmul.[17]

Stela B was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in the early 8th century AD.[17]

Stela C was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in the early 8th century AD.[17]

Stela D was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in the early 8th century AD.[17]

Stela F was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in the early 8th century AD.[17]

Stela H was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in the early 8th century AD.[17]

Stela J was erected by Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil in AD 702 and was his first monument. It stood at the eastern entrance to the city and is unusual in being topped by a sculpted stone roof, converting the monument into a symbolic house. It bears a hieroglyphic text that is woven into a criss-cross mat design to form a convoluted puzzle that must be read in precisely the right order to be understood.[17]

Stela M bears a portrait of K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil. It was raised at the foot of the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Temple 26 in AD 756.[17]

Stela N was dedicated by K'ak' Yipyaj Chan K'awiil in AD 761 and placed at the foot of the steps to Temple 11, which is believed to contain his burial.[48]

Stela P was originally erected in an unknown location and was later moved to the West Court of the Acropolis. It bears a long hieroglyphic text that has not yet been fully deciphered. It dates from the reign of king K'ak' Chan Yopaat and was dedicated in AD 623.[80]

Notes

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 209.

- Martin & Grube2000, pp. 203–205; Looper 2003, p. 76; Miller 1999, pp. 134–135.

- Martin & Grube2000, pp. 206–207.

- Stuart 1996.

- Stuart & Houston 1994, pp. 23, 25.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 198.

- Viel & Hall 2002, p. 877.

- Sheets 2000, p. 434.

- Fasquelle & Fash 2005, p. 4.

- Snow 2010, p. 267.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 203.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 193.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 202.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 196; Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 338.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 192.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 194.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 195.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 196.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 197.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 197–198; Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 336.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 198–199

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 200–201.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 201.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 202–203.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 203–204.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 204–205.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 203, 205.

- Drew 1999, p. 241.

- Looper 2003, p. 79.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 204; Looper 2003, p. 76; Miller 1999, pp. 134–135.

- Drew 1999, p. 286; Looper 2003, p. 78.

- Looper 2003, p. 78.

- Looper 1999, p. 271; Looper 2003, p. 81.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 206.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 208.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 207–208.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 210.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 211.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 212.

- Snow 2010, p. 168.

- Kelly 1996, p. 277.

- Kelly 1996, p. 278.

- Kelly 1996, pp. 278-279.

- Pezzati 2012, p. 5.

- Kelly 1996, p. 279.

- Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp. 335, 339; Fash et al 2005, p.268.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- Schuster 1998.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 205.

- Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp. 334, 340; Martin & Grube 2000, p. 208.

- British Museum Collection

- Sharer & Traxler 2006, pp. 334, 340; Fasquelle & Fash 2005, p. 201.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 193–196.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 199.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 204.

- Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 340; Martin & Grube 2000, p. 204.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 197–198.

- Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 340; Martin & Grube 2000, p. 208.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 200.

- Fasquelle & Fash 2005, p. 201.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 210, 192; Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 341.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 194–196.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 194, 202.

References

- Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo; Fash, Barbara W. (2005). "The Evolution of Structure 10L-16, Heart of the Copán Acropolis". In E. Wyllys Andrews; William L. Fash (eds.). Copán: The History of an Ancient Maya Kingdom. Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.: School of American Research Press. pp. 201–237. ISBN 0-85255-981-X. OCLC 474837429.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drew, David (1999). The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81699-3. OCLC 43401096.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kelly, Joyce (1996). An Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2858-5. OCLC 34658843.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Looper, Matthew G. (1999). "New Perspectives on the Late Classic Political History of Quirigua, Guatemala". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 10 (2): 263–280. doi:10.1017/S0956536199101135. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 86542758.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Looper, Matthew G. (2003). Lightning Warrior: Maya Art and Kingship at Quirigua. Linda Schele series in Maya and pre-Columbian studies. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70556-5. OCLC 52208614.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, Simon; Grube, Nikolai (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05103-8. OCLC 47358325.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pezzati, Alessandro (April 2012). "The Excavation of the Hieroglyphic Stairway at Copan". Pennsylvania Museum Archives. University of Pennsylvania. 54 (1): 4–6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schuster, Angela M.H. (May–June 1998). "Copán Tomb Looted". Archaeology Magazine. Vol. 51 no. 3. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 2010-04-06.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharer, Robert J.; Sedat, David W.; et al. (2005). "Early Classic Power in Copán". In E. Wyllys Andrews; William L. Fash (eds.). Copán: The History of an Ancient Maya Kingdom. Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.: School of American Research Press. pp. 139–199. ISBN 0-85255-981-X. OCLC 474837429.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Traxler, Loa P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheets, Payson D. (2000). "The Southeast Frontiers of Mesoamerica". In Adams, Richard E.W.; Macleod, Murdo J. (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 407–448. ISBN 0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snow, Dean R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. New York: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-615686-4. OCLC 223933566.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stuart, David; Houston, Stephen D. (1994). "Classic Maya Place Names". Studies in pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks (33). OCLC 231630189.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stuart, David (1996). "Hieroglyphs and History at Copán". Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2010-04-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Maya Site of Copan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 8 April 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Viel, René; Hall, Jay (2002). Laporte, J.P.; Escobedo, H.; Arroyo), B. (eds.). "El paisaje natural y cultural del valle de Copan" (PDF). XV Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2001 (in Spanish). Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 872–877. Archived from the original (versión digital) on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2010-02-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Fash, William L.; Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo (2005). "Contributions and Controversies in the Archaeology and History of Copán". In E. Wyllys Andrews; William L. Fash (eds.). Copán: The History of an Ancient Maya Kingdom. Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.: School of American Research Press. pp. 3–32. ISBN 0-85255-981-X. OCLC 474837429.

- Fash, William L.; Andrews, E. Wyllys; Manahan, T. Kam (2005). "Political Decentralization, Dynastic Collapse, and the Early Postclassic in the Urban Center of Copán, Honduras". In Arthur A. Demarest; Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice (eds.). The Terminal Classic in the Maya lowlands: Collapse, transition, and transformation. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. pp. 260–287. ISBN 0-87081-822-8. OCLC 61719499.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Copán. |

| Wikisource has a poem by Clark Ashton Smith called Copan (1912): |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 94.

- "Copan" at Curlie

- "Lost King of the Maya" companion site to PBS's "Nova" television documentary on Copán

- Copan Sculpture Museum: Ancient Maya Artistry in Stucco and Stone. Barbara Fash. Published by the Peabody Museum Press. Paperback 2011