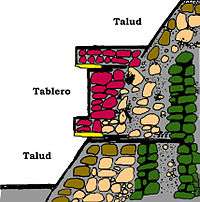

Talud-tablero

Talud-tablero is an architectural style most commonly used in platforms, temples, and pyramids in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, becoming popular in the Early Classic Period of Teotihuacan. Talud-tablero consists of an inward-sloping surface or panel called the talud, with a panel or structure perpendicular to the ground sitting upon the slope called the tablero. This may also be referred to as the slope-and-panel style.

Cultural significance

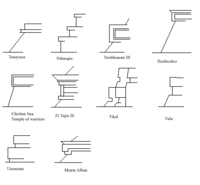

Talud-tablero was often employed in pyramid construction, found in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. It is found in many cities and cultures but is strongly associated with the Teotihuacan culture of central Mexico, where it is a dominant architectural style. Talud-tablero's appearance in many cities during and after Teotihuacan's apogee is thought to be indicative of the city's powerful influence in Mesoamerica as a trade, art, and cultural center, with the architectural style serving to either emulate Teotihuacan or affiliate the cities together.[2] Teotihuacan's influence was especially evident in newer settlements that developed during the Early Classic Period, which adopted the talud-tablero architectural style and may have utilized guidance from the city to become trading centers themselves.[3] After the fall of Teotihuacan, other cities may have adopted the talud-tablero style not for its direct affiliation with Teotihuacan, but because of the power it symbolized due to the many successful cultures that had adopted it.[3]

Many different variants on the talud-tablero style arose throughout Mesoamerica, developing and manifesting themselves differently among the various cultures. In some cases, such as the Maya city of Tikal, the introduction of talud-tablero architecture during the Early Classic corresponds with direct contact with Teotihuacan and possible domination or conquest.[4] However, the form of contact at other cities is less well documented and presumably included trade and cultural contacts. A competing theory by Juan Pedro Laporte postulates that Tikal may have developed talud-tablero independently from Teotihuacan based on their extensive use of apron molding in their architecture that may have been a precursor to the slope-and-panel.[5]

Sites featuring Talud-tablero

The earliest examples of talud-tablero constructions date not from the Teotihuacan Early Classic Period, however, but are found in Pre-Classic constructions in the Tlaxcala-Puebla region,[6] with the oldest known dating to c. 200 BC in the Mexican city of Tlalancaleca. It is unknown if Teotihuacan developed their version of the style based on that of Tlalancaleca or if they did so independently.[7] Teotihuacan strongly influenced many other cities which allowed for the architectural style of talud-tablero to be adapted into these cities all over Mesoamerica. Cities and their structures using talud-tablero include:

- Cholula-Epiclassic Period- Evidence of talud-tablero was found in previous pyramids beneath the final layer of the Great Pyramid.[8] Talud-tablero is also mimicked in the creation of the terraces at Cholula.[9]

- Kaminaljuyu site in Guatemala-Classic Period- Talud-tablero style tombs were used for the elite of the city.[10]

- Matacapan-Classic Period- The center pyramid of the city was created using the talud-tablero style after the city was directly influenced by Teotihuacan.[11]

- Monte Albán-Classic Period- Many structures in Monte Alban have a similar style to Teotihuacan's talud-tablero, but with a modified panel.[12]

- Nakum- Nakum used thetalud-tablero style on the interior side of four pyramids that surrounded Patio 1 in the city.[13]

- Teotihuacan- Most structures in Teotihuacan were created by using the talud-tablero style. The most notable structures using talud-tablero include the Temple of the Sun, Temple of the Moon, and Temple of Quetzalcoatl.[14]

- Tikal-Classic Period- Tikal has a structure using talud-tablero that dates to around A.D. 200 and the next large structure seeming to be directly influenced by Teotihucan with talud-tablero on two sides of a pyramid.[15]

- Xochicalco- The greatest structure of Xochicalco is the Temple of the Feathered Serpent that was created using talud-tablero.[16]

Talud-tablero in Tikal Structure 5C-49

Talud-tablero in Tikal Structure 5C-49 Example of Talud Tablero Architecture in Tikal

Example of Talud Tablero Architecture in Tikal- Talud-tablero in Structure 17 at Calixtlahuaca

- Talud-tablero present on platform along Avenue of the Dead, Teotihuacan

- Great Pyramid of Cholula, Puebla, Mexico

Other sites where talud-tablero architecture can be found include but are not limited to:

| Early Classic | Middle Classic | Late Classic | Post Classic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholula | Tonina | Mitla | Tulum |

| Becan | Dzibilchaltun | Mexiquito | Tancah |

| Teotihuacan | Chinkultic | Teotenango | Tlatelolco |

| Edzna | Cacaxtla | Tula | Tenochititlan |

| Tepeapulco | Xochicalco | Chichen Itza | |

| Solano | El Ixtepete | ||

| Tikal | Copán | ||

| Monte Albán | |||

| Calixtlahuaca | |||

| Yohulichan | |||

| Ake | |||

| Kaminaljuyu | |||

| Oxkintok | |||

| Matacapan | |||

| Tazumal | |||

| Tingambato | |||

| El Tajín | |||

| Palenque |

Notes

- Illustration adapted from Weaver (1993, p.251)

- Giddens (1995, p.40)

- Giddens (1995, p. 70)

- Martin and Grube (2000, pp.29–31)

- Laporte (1985)

- Braswell (2003, p.11)

- Garcia Cook (1984)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, pp.125)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, pp.144)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, p.122)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, p.127)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, p.131)

- Koszkul, Hermes, and Calderon (2006, p.121)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, p.112)

- Giddens (1995, p.59)

- Coe and Koontz (2013, p.141)

- Giddens (1995, p. 82)

See also

References

- Braswell, Geoffrey E. (2003). "Introduction: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction". In Geoffrey E. Braswell (ed.). The Maya and Teotihuacan: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 1–44. ISBN 0-292-70587-5. OCLC 49936017.

- Coe, Michael D.; Koontz, Rex (2013). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500290767.

- Garcia Cook, Angel (1973). "Algunos descumbrimientos en Tlalancaleca". Communicaciones de Proyecto Puebla-Tlaxcala. Fundación Alemana para la Investigación Científica, Puebla, Mexico. 9: 25–34.

- Giddens, Wendy Louise (1995). Talud-Tablero Architecture as a Symbol of Mesoamerican Affiliation and Power (Masters). University of California.

- Harris, Cyril M. (1983). Illustrated Dictionary of Historic Architecture (originally published as: Historic Architecture Sourcebook (New York: McGraw-Hill ©1977), reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24444-X. OCLC 8806282.

- Koszkul, Wieslaw; Hermes, Bernard; Calderon, Zoila (December 2006). "Teotihucan-related Finds from the Maya Site of Nakum, Peten, Guatemala". Mexicon. 28: 117–127.

- Laporte, Juan Pedro (1985). "El 'Talud Tabler' en Tikal, Peten: Nuevos Datos". Vida y Obra de Roman Pina Chan. Instituto de Investigaciones Anthropologicas.

- Martin, Simon; Nikolai Grube (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05103-8. OCLC 47358325.

- Weaver, Muriel Porter (1993). The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-739065-0. OCLC 25832740.

External links

- Definition of Talud-tablero Archeology Wordsmith

- Teotihuacano art and architecture University of Texas

- Locating the Place and Meaning of the Talud-Tablero Architectural Style in the Early Classic Maya Built Environment Doctoral Dissertation by Crtistin Cash