Jade use in Mesoamerica

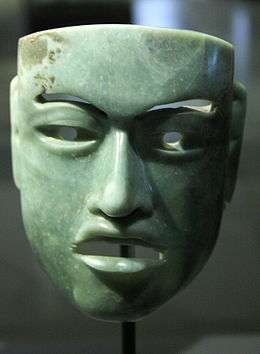

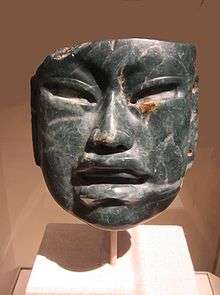

The use of jade in Mesoamerica for symbolic and ideological ritual was highly influenced by its rarity and value among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Olmec, the Maya, and the various groups in the Valley of Mexico. Although jade artifacts have been created and prized by many Mesoamerican peoples, the Motagua River valley in Guatemala was previously thought to be the sole source of jadeite in the region.

This extreme durability makes fine grained or fibrous jadeite and nephrite highly useful for Mesoamerican technology. It was often worked or carved as ornamental stones, a medium upon which glyphs[1] were inscribed, or shaped into figurines, weapons, and other objects. Many jade artifacts crafted by later Mesoamerican civilizations appear cut from simple jade axes, implying that the earliest jadeite trade was based in utilitarian function.

Jade and Jadeite

In general terms, jade refers to two distinct minerals: nephrite, a calcium and magnesium rich amphibole mineral, and jadeite, a pyroxene rich in sodium and aluminum. A general misconception is that nephrite does not naturally exist in Mesoamerica. However, the Middle Motagua River Valley area that yields jadeite also yields nephrite although Mesoamerican artisans had less interest in working nephrite.[2] Colloquially 'jade' objects in Mesoamerica are composed of jadeite, but may also refer to other similar-looking, relatively hard greenstones such as albitite, omphacite, chrysoprase, and quartzite.[3]

Variation in color is largely due to variation in trace element composition. In other words, the types of trace elements and their quantities affect the overall color of the material. “Olmec Blue” jade, characterized by an icelike shade of pale blue, owes its unique color to the presence of iron and titanium, while the more typical green jade’s color is due to the varying presence of sodium, aluminum, iron, and chromium. Translucence can vary as well, with specimens ranging from nearly clear to completely opaque.

Sources in Mesoamerica

The archaeological search for the Mesoamerican jade sources, which were largely lost at the time of the Maya collapse, began in 1799 when Alexander von Humboldt started his geological research in the New World. Von Humboldt sought to determine whether or not Neolithic jadeite celts excavated from European Megalithic archaeological sites like Stonehenge and Carnac shared sources with the similar looking jade celts from Mesoamerica (they do not).

The first discovery of in-situ jade quarries was made by archeologist Mary Lou Ridinger in 1974.[4] Previous to this discovery, academic consensus had not been reached regarding the true source of jade used by the Maya and debate continued for some time after, though it is now accepted as the first conclusive discovery of the sources of jade that the Maya culture had used. Since the first discovery, Ridinger also discovered many varieties of Central American jadeite that had never before been seen, such as lilac jade and a variety of jadeite with pyrite inclusions.[5]

From 1974 to 1996, the only documented source of jadeite in Mesoamerica was the lowland Motagua River valley. Research conducted by the Mesoamerican Jade Project of Harvard's Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology between 1977 and 2000 led to the identification of both the long lost 'Olmec Blue' mines, a discovery published by Mesoamerican Jade project Field Director Russell Seitz and his colleagues from the American Museum of Natural History in Antiquity in December 2001. In addition, they conducted geochemical dating of several ancient Maya lode mines and alluvial sources in the mountainous areas on both sides of the Motagua. Following their exposure by the torrential rains of Hurricane Mitch in 1998, alluvial cobbles of blue jade were traced up a southern Motagua tributary, the Rio Tambor, to massive outcrops of fine grained translucent 'Olmec Blue' jadeite, at elevations of between 1200 and 3800 feet in the province of Jalapa, along a fault extending from Carrizal Grande to La Ceiba. Geochemical dating revealed that the southern deposits, including the archaeologically important translucent blue jade, were ~40 MA older that the coarse grained opaque jades mined for sale to tourists, or those from the higher elevations around a northern Motagua tributary, the Rio Blanco, where jadeite outcrops are found at elevations of up to an elevation of 6,000 feet and several of the ancient mining sites are connected by dry-laid stone paths.

It is noteworthy that the richest 'Olmec Blue' source area, far from being in 'the Motagua Valley' lies about 50 km southwest of Copán. Since the Motagua becomes Guatemala's border with Honduras, Honduras may host alluvial jade as well. The rediscovered 'Olmec' jade is of the quality traded throughout formative Mesoamerica, reaching areas as distant as the Valley of Mexico and Costa Rica. While Pool notes that "for many years, it had been suggested that there might be another source in the Balsas River valley", no such Mexican source has come to light; However, recent work has revealed that the high pressure-low temperature metamorphic rocks (blueschist facies) hosting jade deposits in Guatemala also outcrop as jadeite boulder bearing serpentine melange deposits at several places in Cuba and Hispaniola, where the material was exploited by the Taino and Carib cultures. Jade artifacts, mainly pointed celts, apparently stemming from these Antillean sources have been excavated as far east as Antigua in the Windward Islands. Given the scope and duration of the regional tectonic processes that created and exhumed these jade deposits, they may well extend into Chiapas as well.

Uses

Art

Jade was shaped into a variety of objects including, but not limited to, figurines, celts, ear spools (circular earrings with a large hole in the center), and teeth inlays (small decorative pieces inserted into the incisors). Mosaic pieces of various sizes were used to decorate belts and pectoral coverings.

A good example of jadeite garb is the Mayan Leiden Plaque. The plaque was known more as a portable stella, with hieroglyphs and narratives inscribed on its face. The markings provide a scene of a Maya lord standing with one foot on top of a captive.[1]

Jade sculpture often depicted deities, people, shamanic transformations, animals and plants, and various abstract forms. Sculptures varied in size from single beads, used for jewelry and other decorations, to large carvings, such as the 4.42 kilogram head of the Maya sun god found at Altun Ha. Jade workshop areas have been documented at two Classic Maya sites in Guatemala: Cancuen and Guaytán. The archaeological investigation of these workshops has informed researchers on how jadeite was worked in ancient Mesoamerica.

Religion

The value of jade went beyond its material worth. Perhaps because of its color, mirroring that of water and vegetation, it was symbolically associated with life and death and therefore possessed high religious and spiritual importance.

The Maya placed jade beads in the mouth of the dead. Michael D. Coe has suggested that this practice relates to a sixteenth-century funerary ritual performed at the deaths of Pokom Maya lords: "When it appears then that some lord is dying, they had ready a precious stone which they placed at his mouth when he appeared to expire, in which they believe that they took the spirit, and on expiring, they very lightly rubbed his face with it. It takes the breath, soul or spirit."

Bishop Landa has associated the placement of jade beads in the mouths of the dead with symbolic planting and rebirth of the maize god.[6] Precious offerings depicting maize have been found in the Sacred Cenote, paralleling the interment of the Maize God himself entering the underworld. Many objects found were considered uniquely beautiful, and had been exquisitely crafted before offered as sacrifice.[7]

The Maya also associated jade with the sun[8] and the wind. Many Maya jade sculptures and figurines of the wind god have been discovered, as well as many others displaying breath and wind symbols. In addition, caches of four jade objects placed around a central element which have been found are believed to represent not only the cardinal directions, but the directional winds as well.

Elite Mayans wore jade pendants that depicted "mirror gods" associated with rulership in Mesoamerica.[9] Mirror divination was a part of spiritual practice in Mayan culture, and the Mayan sun god, Kinich Ahau, was often depicted in jade and other materials with a mirror on his forehead. The reflective quality of highly polished jade connected itself to other mirrored objects, promoting its spiritual importance and aesthetic value to the Maya.[9]

The aesthetic and religious significance of the various colors remains a source of controversy and speculation. The bright green varieties may have been identified with the young Maize God. The Olmec were fascinated with the unique blue jade of Guatemala and it played an important role in their rituals involving water sources. The Olmec used blue jade because it represented water, an Olmec iconography representing the Underworld. Blue also represented the blue color that snakes turn before shedding their skin; therefore, blue represents aquatic and serpentine rejuvenation.

Working jade

Next to emery, jade was the hardest mineral known to ancient Mesoamerica.[10] In the absence of metal tools, ancient craftsmen used tools themselves made of jade, leather strops, string saws to cut and carve jade, and reeds or other hard materials to drill holes. (Mesoamerican artisans also used jade tools to work other stones.) Working the raw stone into a finished piece was a very labor-intensive process, often requiring repeated physical movement to shape the jade.[11] It would take many hours of work to create even a single jade bead.[12]

Craftsmen employed lapidary techniques such as pecking, percussion, grinding, sawing, drilling, and incising to shape and decorate jade. Several of these techniques were thought to imbue pieces with religious or symbolic meaning. For instance, drilling holes into jade was thought to give a piece "life," or animate, a carving.[11]

In addition to being an elite good of highly symbolic use in the performance of ideological ritual, the high pressure minerals that form these translucent rocks are much tougher and more damage resistant than slightly harder but far more brittle materials such as flint.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jade artefacts from Mesoamerica. |

- Howard, Kim Be (n.d.). "Jadeite" (PDF reprinted online). Gemmology Canada. Vancouver: Canadian Institute of Gemmology. ISSN 0846-3611. OCLC 25590010.

- Middleton, Andrew (2006). "Jade – Geology and Mineralogy". In Michael O'Donoghue (ed.). Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification (6th ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 332–354. ISBN 978-0-7506-5856-0. OCLC 62088437.

- Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.

- Pool, Christopher A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3. OCLC 68965709.

- Seitz, R.; G.E. Harlow; V.B. Sisson; K.A. Taube (December 2001). "'Olmec Blue' and Formative jade sources: new discoveries in Guatemala" (PDF online facsimile). Antiquity. Cambridge, England: Antiquity Publications. 75 (290): 687–688. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.424.750. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00089171. ISSN 0003-598X. OCLC 93889951.

- Wagner, Elisabeth (2006). "Jade – the Green Gold of the Maya". In Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann Press. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

References

- Ellen., Miller, Mary (2012). The art of Mesoamerica : from Olmec to Aztec (Fifth ed.). London. ISBN 978-0500204146. OCLC 792747355.

- Ancient Maya art at Dumbarton Oaks. Pillsbury, Joanne., Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. 2012. ISBN 978-0884023753. OCLC 731372976.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pool (2007, p.150).

- https://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/24/travel/a-mayan-past-a-latin-present-in-guatemala.html?pagewanted=2

- http://www.natchezdemocrat.com/1999/10/19/archaeologist-tells-story-of-lost-jade-mines/

- Miller, Mary (Spring 1998). "Where Maize May Grow: Jade, Chacmools, and the Maize God". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 33 (33): 58. doi:10.1086/RESv33n1ms20167001. JSTOR 20167001.

- Miller, Mary (1998). "Where Maize May Grow: Jade, Chacmools, and the Maize God". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. 33: 56. doi:10.1086/RESv33n1ms20167001.

- Miller (1999, p.74).

- John B. Carlson, “The Jade Mirror: An Olmec Concave Jade Pendant,” in Precolumbian Jade: New Geological and Cultural Interpretations, ed. Frederick W Lange (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1993), 242–50.

- Miller (1999, p.73).

- Ancient Maya art at Dumbarton Oaks. Pillsbury, Joanne., Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. 2012. ISBN 9780884023753. OCLC 731372976.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pool, p. 151.