Izamal

Izamal (Spanish: [isaˈmal] (![]()

Izamal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): The Yellow City | |

Location of Izamal, Yucatan | |

| Coordinates: 20°55′53″N 89°01′04″W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| State | Yucatan |

| Municipality | Izamal |

| City Founded | December 4, 1841 |

| Elevation | 13 m (43 ft) |

| Population (INEGI, 2005)[1] | |

| • Total | 15,101 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central Daylight Time) |

| ZIP code | 97540[2] |

| Area code(s) | 988 |

| INEGI Code | 310400001[3] |

| Website | www |

Izamal was continuously occupied throughout most of Mesoamerican chronology; in 2000, the city's estimated population was 15,000 people. Izamal is known in Yucatán as the Yellow City (most of its buildings are painted yellow) and the City of Hills (that actually are the remains of ancient temple pyramids).

Pre-Columbian Izamal

Izamal is an important archaeological site of the Pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is probably the biggest city of the Northern Yucatec Plains, covering a minimal urban extension of 53 square kilometres (20 sq mi). Its monumental buildings exceed 1,000,000 cubic meters of constructive volume and at least two raised causeways, known by their Mayan term sacbeob, connect it with other important centers, Ruins of Ake, located 29 kilometres (18 mi) to the west and Kantunil, 18 kilometers to the south, evidencing the religious, political and economic power of this political unit over a territory of more than 5,000 square kilometres (1,900 sq mi) in extension. Izamal developed a particular constructive technique involving use of megalithic carved blocks, with defined architectonical characteristics like rounded corners, projected mouldings and thatched roofs at superstructures, which also appeared in other important urban centers within its hitherland, such as Ake, Uci and Dzilam.

The city was founded during the Late Formative Period (750–200 BC) and was continuously occupied until the Spanish Conquest. The most important constructive activity stage spans between Protoclassic (200 BC – 200 AD) and Late Classic (600–800 AD). It was partially abandoned with the rise of Chichen Itza in the Terminal Classic (800–1000 A.D.) until the end of the Precolumbian era, when Izamal was considered a site of pilgrimages in the region, rivaled only by Chichen Itza. Its principal temples were sacred to the creator deity Itzamna and to the Sun god Kinich Ahau.

Five huge Pre-Columbian structures are still easily visible at Izamal (and two from some distance away in all directions). The first is a great pyramid to the Maya Sun god, Kinich Kak Moo (makaw of the solar fire face) with a base covering over 2 acres (8,000 m²) of ground and a volume of some 700,000 cubic meters. Atop this grand base is a pyramid of ten levels. To the south-east lies another great temple, called Itzamatul, and placed at the south of what was a main plaza, another huge building, called Ppap Hol Chak, was partially destroyed with the construction of a Franciscan temple during the 16th century.

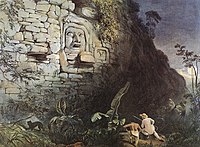

The south-west side of the plaza is partially limited by another pyramid, the Hun Pik Tok, and in the west lie the remains of the temple known as Kabul, where a great stucco mask still existed on one side as recently as the 1840s, as seen in a colored lithograph after a drawing by Frederick Catherwood. All these large man-made mounds probably were built up over several centuries and originally supported city palaces and temples. Other important residential buildings which have been restored and can be visited are Xtul (The Rabbit), Habuc and Chaltun Ha.

After more than a decade of archaeological work done by Mexican archaeologists at Izamal, over 163 archaeologically important structures have been found there, and thousands of residential structures at surrounding communities have been located.

Spanish Colonial era

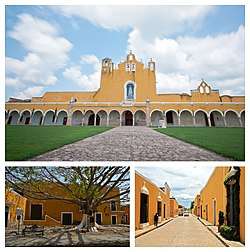

After the Spanish conquest of Yucatán in the 16th century a Spanish colonial city was founded atop the existing Maya one; however it was decided that it would take a prohibitively large amount of work to level these two huge structures and so the Spanish contented themselves with placing a small Christian temple atop the great pyramid and building a large Franciscan Monastery atop the acropolis. It was named after San Antonio de Padua. Completed in 1561, the open atrium of the Monastery is still today second in size only to that at the Vatican. Most of the cut stone from the Pre-Columbian city was reused to build the Spanish churches, monastery, and surrounding buildings.

Izamal was the first chair of the Bishops of Yucatán before they were moved to Mérida. The fourth Bishop of Yucatán, Diego de Landa lived here.

Modern history

The town of Izamal was first granted the status of city by the government of Yucatán on 4 December 1841. On 13 August 1923 it was demoted to town status. It was again officially ranked as a city on 1 December 1981.

In 1975 the official in charge of land redistribution was repeatedly accused of political corruption; letters of complaint were sent from citizens of Izamal to Mérida and Mexico City with no response. The official was found stoned to death under a large pile of rocks in the town's main square. A Mexican Army unit occupied the town for some days after the incident, but investigators failed to find anyone in town who knew anything about what happened.

Pope John Paul II visited Izamal in August 1993, where he performed a mass and presented the statue of the Virgin with a silver crown.[4]

Present day

Izamal remains a place of pilgrimage within the Yucatán state, now for the veneration of Roman Catholic saints. Several saints statues at Izamal are said to perform miracles. An early colonial era statue of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception ("Our Lady of Izamal") is particularly venerated, and is the Yucatan state's patron saint.[5]

The Maya language is still heard at least as much as Spanish in Izamal. It is the first language in the homes of the majority of the people. Most signs are in both languages.

Major Fiestas are held in Izamal on April 3, May 3, August 15, and December 8.

Izamal is the home of a distillery which produces an eponymous mezcal from the hearts of the locally grown agave plants.

Izamal was named a "Pueblo Mágico" in 2002.[6]

Climate

| Climate data for Izamal | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.7 (92.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31 (88) |

30.4 (86.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17 (63) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38 (1.5) |

30 (1.2) |

20 (0.8) |

23 (0.9) |

81 (3.2) |

140 (5.6) |

130 (5.2) |

160 (6.4) |

190 (7.4) |

97 (3.8) |

33 (1.3) |

30 (1.2) |

980 (38.5) |

| Source: Weatherbase [7] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

Main arcade of convent and church entrance

Main arcade of convent and church entrance- The placid streets of Izamal

- Monastery facade

Arcade with pyramid in background

Arcade with pyramid in background Convent as viewed from atop Kinich Kak Mo pyramid

Convent as viewed from atop Kinich Kak Mo pyramid

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2005). "Principales resultados por localidad (ITER)". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- Alternativo Networks, Inc. "Buscador de Códigos Postales en México" (in Spanish). Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- INEGI. "Archivo Histórico de Localidades. Izamal" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- "Yucatan News: Izamal's Favorite Pope". Yucatanliving.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Casinos unter die Lupe genommen – Das Mummysgold Casino – sicher, kompetent und vertrauensvoll". Colonial-mexico.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "HISTORY OF IZAMAL". Izamal.info. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Izamal, Yucatán". Weatherbase. 2011. Retrieved on November 24, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Izamal. |

- Izamal's monastery on colonial-mexico.com with photos and a map of the center of town

- Izamal by Yucatan Today

- Izamal Photo Essay