Ekʼ Balam

Ekʼ Balam ek-bælæm is a Yucatec-Maya archaeological site within the municipality of Temozón, Yucatán, Mexico. It lies in the Northern Maya lowlands, 25 kilometres (16 mi) north of Valladolid and 56 kilometres (35 mi) northeast of Chichen Itza. From the Preclassic until the Postclassic period, it was the seat of a Mayan kingdom.

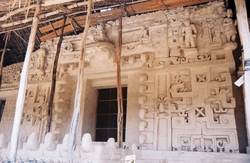

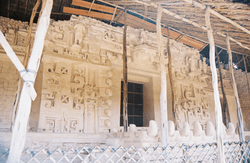

The site is noted for the preservation of the plaster on the tomb of Ukit Kan Lek Tokʼ, a king buried in the side of the largest pyramid.[1]

History

Ekʼ Balam was occupied from the Middle Preclassic through the Postclassic, although it ceased to thrive as a major city past the Late Classic. Beginning in the Late Preclassic, the population grew and the city expanded throughout the following periods. It eventually became the capital of the polity that controlled the region around the beginning of the Common Era.[2]

At its height from 770 to 840 CE, Ekʼ Balam provides a rich resource of information for understanding northern Classic cities, due to the poor preservation of many other notable northern Maya sites (e.g. Coba, Izamal, and Edzna).[3] It was during this height that the Late Yumcab ceramic complex (750-1050/1100 CE) dominated the architecture and pottery of Ekʼ Balam.[2] The population decreased dramatically, down to 10% of its highest, during the Postclassic period as Ekʼ Balam was slowly becoming vacant.[4] There are several theories to why it was eventually abandoned and to the degree of haste at which it was abandoned (see: Defensive Walls).

Ek Balam is mentioned in a late-sixteenth-century Relación Geográfica, an official inquiry held by the colonial government among local Spanish landowners. It is reported to have belonged to a kingdom called 'Talol',[5] founded by an Ekʼ Balam, or Coch Cal Balam, who had come from the East. Later, the region was dominated by the aristocratic Cupul family.

Architecture

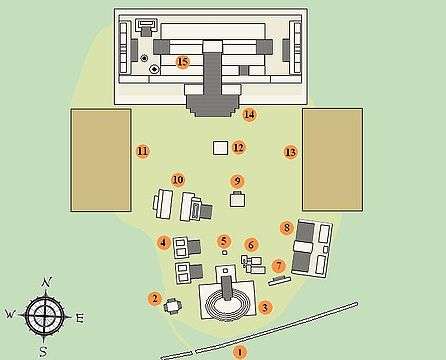

There are 45 structures, including:

- These are the city's Defensive Walls, which end on both sides at an unsurpassable, steep sink hole.[6]

- The Entrance Arch stands at the entrance of Ekʼ Balam on four legs, constructed over the road that leads into the city, and was probably ceremonial in purpose.[7]

- The Oval Palace contained burial relics and its alignment is assumed to be connected to cosmological ceremonies.[7]

- Structure 17 or The Twins atop of which there are two mirroring temples on either side.

- Chapel

- A carved stela which depicts a ruler of Ek Balam, possibly Ukit Kan Leʼk Tokʼ.

- Structure 12

- Structure 10 is a platform whose base dates to the Late Classic but was built upon by later generations.[7]

- Structure 7

- The Ballcourt was completed in 841.[7]

- Structure 2 on the west corner of the Acropolis is one of the large platforms that make up the main plaza and contains a temple in one corner.[7]

- Steam Bath

- Structure 3 on the east corner of the Acropolis is an unexcavated platform that borders the main plaza.[7]

- Structure 1 or the Acropolis on the north side of the site is the largest structure at Ekʼ Balam and is believed to contain the tomb of Ukit Kan Leʼk Tokʼ, an important ruler in Ekʼ Balam. Excavations on it began in 1998, when it was just a mound.[7]

- This is the temple in which Ukit Kan Leʼk Tokʼ was buried, called El Trono ('The Throne'). The doorway is in the shape of a monster-like mouth, possibly depicting a jaguar.[7]

Notable Features

Defensive Walls

The layout of the site is surrounded by two concentric walls which served as defense against attack. There were many smaller walls that snaked through the city as well. The inner wall encompasses an area of 9.55 hectares (23.6 acres). The carved stone of the inner wall, 2 metres (6.6 ft) tall and 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide, is covered in plaster; the outer wall serves purely for defense, as it is less substantial and less decorative. These walls were the largest in the Late Classic Yucatan, and seem to have a symbolic meaning of protection and military strength. Theories claiming a hasty desertion of the city are backed up by the fourth wall inside the city, which "bisects the Great Plaza, and, at less than a meter wide and made of poorly constructed rubble, it was clearly built as a last ditch effort at protection" against invading attackers.[6]

Structures Inside the Walls

Only the center of Ekʼ Balam has been excavated. Large, raised platforms line the interior wall, surrounding internal plazas. Sacbé roads stem off of the center in the four cardinal directions, an architectural allusion to the idea of a "four-part cosmos".[5] These roads are often understood to have been sacred.[6][7] The buildings were designed in the northern Petén architectural style, as were the surrounding large cities of the time, although it has its dissimilarities with them as well.[5]

The Acropolis houses the tomb of king Ukit Kan Leʼk Tok', who ruled from 770 (the starting year of the "height" of this city) to 797 or 802 CE.

Wall Paintings

In rooms of the Acropolis, wall paintings consisting of texts have been found, amongst these the 'Mural of the 96 Glyphs', a masterwork of calligraphy comparable to the 'Tablet of the 96 Glyphs' from Palenque.[8] Another wall painting of the Acropolis features a mythological scene with a hunted deer, which has been interpreted as the origin of death.[9] A series of vault capstones depict the lightning deity, a specific decoration also known from other Yucatec sites.[8]

View from the top

On a clear day, from the top of the Acrópolis, temples of Cobá and Chichén Itzá can be seen on the horizon.

- Temple Ixmoja of Cobá is approximately at azimuth 135° (Southeast) at a distance of 65 km.

- El Castillo of Chichén Itzá is approximately at azimuth 242° (West-Southwest) at a distance of 55 km.

Archaeological Research

Ekʼ Balam was rediscovered and explored first by influential archaeologist Désiré Charnay in the late 1800s but extensive excavation did not take place until a century later.[7] Bill Ringle and George Bey III mapped the site in the late 1980s, and continued to do extensive research into the 1990s, their works being cited by many others who later write on the site. Subsequently, the Acropolis was excavated by Leticia Vargas de la Peña and Víctor Castillo Borges from the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.[5] Alfonso García-Gallo Lacadena deciphered the most important set of North Maya Maya hieroglyphic texts and all historical references of Ek Balam are based on his intellectual work.[10]

Gallery

Structure III and Structure X

Structure III and Structure X Pillars on 'The Acropolis'

Pillars on 'The Acropolis' Close-up of carving

Close-up of carving Stucco facade.

Stucco facade. Jaguar Altar (Left)

Jaguar Altar (Left) Structure II and west side of 'The Acropolis'

Structure II and west side of 'The Acropolis'- Stucco jaws principal pyramid of Ek Balam(Yucatan)

Oval palace Ek Balam

Oval palace Ek Balam- Winged Maya Warriors

See also

References

- O'Neill, Zora; Fisher, John (2008). The Rough Guide to the Yucatan (second ed.). London: Rough Guides (Penguin). pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-1-85828-805-5.

- Bey III, et al (1998)

- Martin and Grube (2000)

- Aimers (2007)

- Witschey and Brown (2011)

- Dahlin (2000)

- Rider (2005)

- Lacadena 2004

- Chinchilla Mazariegos 2011: 167 figs. 65, 66

- Lacadena García-Gallo, A. 2002. El corpus glífico de Ekʼ Balam (Yucatán, México) (Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI).

Bibliography

- Aimers, James J. "What Maya Collapse? Terminal Classic Variation in the Maya Lowlands." Journal of Archaeological Research 15.4 (2007): 329-77.

- Bey III, George J., et al. "The Ceramic Chronology of Ek Balam, Yucatan, Mexico." Ancient Mesoamerica. 9. (1998): 101-20.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo. Imágenes de la mitología maya. Guatemala: Museo Popol Vuh, 2011.

- Dahlin, Bruce H. "The Barricade and Abandonment of Chunchucmil: Implications for Northern Maya Warfare." Latin American Antiquity. 11.3 (2000): 283-98.

- Lacadena, Alfonso, 'The Glyphic Corpus from Ekʼ Balam, Yucatán, Mexico', FAMSI report 2004.

- Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. 2nd ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

- Rider, Nick. Yucatan & Mayan Mexico, 3rd. 3rd. Cadogan Guides, 2005.

- Witschey, Walter R. T., and Clifford T. Brown. Historical Dictionary of Mesoamerica. illustrated. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2011. Web.

- Photos of Ekʼ Balam

- Recent Finds at Ekʼ Balam at Mesoweb

- based on Hofling at famsi.org

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ek' balam. |