Comedy

In a modern sense, comedy (from the Greek: κωμῳδία, kōmōidía) is a genre of fiction that refers to any discourse or work generally intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, television, film, stand-up comedy, books or any other medium of entertainment. The origins of the term are found in Ancient Greece. In the Athenian democracy, the public opinion of voters was influenced by the political satire performed by the comic poets at the theaters.[1] The theatrical genre of Greek comedy can be described as a dramatic performance which pits two groups or societies against each other in an amusing agon or conflict. Northrop Frye depicted these two opposing sides as a "Society of Youth" and a "Society of the Old."[2] A revised view characterizes the essential agon of comedy as a struggle between a relatively powerless youth and the societal conventions that pose obstacles to his hopes. In this struggle, the youth is understood to be constrained by his lack of social authority, and is left with little choice but to take recourse in ruses which engender very dramatic irony which provokes laughter.[3]

| Literature |

|---|

|

| Major forms |

| Genres |

| Media |

| Techniques |

| History and lists |

| Discussion |

|

|

Satire and political satire use comedy to portray persons or social institutions as ridiculous or corrupt, thus alienating their audience from the object of their humor. Parody subverts popular genres and forms, critiquing those forms without necessarily condemning them.

Other forms of comedy include screwball comedy, which derives its humor largely from bizarre, surprising (and improbable) situations or characters, and black comedy, which is characterized by a form of humor that includes darker aspects of human behavior or human nature. Similarly scatological humor, sexual humor, and race humor create comedy by violating social conventions or taboos in comic ways. A comedy of manners typically takes as its subject a particular part of society (usually upper-class society) and uses humor to parody or satirize the behavior and mannerisms of its members. Romantic comedy is a popular genre that depicts burgeoning romance in humorous terms and focuses on the foibles of those who are falling in love.

Etymology

The word "comedy" is derived from the Classical Greek κωμῳδία kōmōidía, which is a compound of κῶμος kômos (revel) and ᾠδή ōidḗ (singing; ode).[4] The adjective "comic" (Greek κωμικός kōmikós), which strictly means that which relates to comedy is, in modern usage, generally confined to the sense of "laughter-provoking".[5] Of this, the word came into modern usage through the Latin comoedia and Italian commedia and has, over time, passed through various shades of meaning.[6]

The Greeks and Romans confined their use of the word "comedy" to descriptions of stage-plays with happy endings. Aristotle defined comedy as an imitation of men worse than the average (where tragedy was an imitation of men better than the average). However, the characters portrayed in comedies were not worse than average in every way, only insofar as they are Ridiculous, which is a species of the Ugly. The Ridiculous may be defined as a mistake or deformity not productive of pain or harm to others; the mask, for instance, that excites laughter is something ugly and distorted without causing pain.[7] In the Middle Ages, the term expanded to include narrative poems with happy endings. It is in this sense that Dante used the term in the title of his poem, La Commedia.

As time progressed, the word came more and more to be associated with any sort of performance intended to cause laughter.[6] During the Middle Ages, the term "comedy" became synonymous with satire, and later with humour in general.

Aristotle's Poetics was translated into Arabic in the medieval Islamic world, where it was elaborated upon by Arabic writers and Islamic philosophers, such as Abu Bishr, and his pupils Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes. They disassociated comedy from Greek dramatic representation and instead identified it with Arabic poetic themes and forms, such as hija (satirical poetry). They viewed comedy as simply the "art of reprehension", and made no reference to light and cheerful events, or to the troubling beginnings and happy endings associated with classical Greek comedy.

After the Latin translations of the 12th century, the term "comedy" gained a more general meaning in medieval literature.[8]

In the late 20th century, many scholars preferred to use the term laughter to refer to the whole gamut of the comic, in order to avoid the use of ambiguous and problematically defined genres such as the grotesque, irony, and satire.[9][10]

History

Western history of comedy

Dionysiac origins, Aristophanes and Aristotle

Starting from 425 BCE, Aristophanes, a comic playwright and satirical author of the Ancient Greek Theater, wrote 40 comedies, 11 of which survive. Aristophanes developed his type of comedy from the earlier satyr plays, which were often highly obscene.[11] The only surviving examples of the satyr plays are by Euripides, which are much later examples and not representative of the genre.[12] In ancient Greece, comedy originated in bawdy and ribald songs or recitations apropos of phallic processions and fertility festivals or gatherings.[13]

Around 335 BCE, Aristotle, in his work Poetics, stated that comedy originated in phallic processions and the light treatment of the otherwise base and ugly. He also adds that the origins of comedy are obscure because it was not treated seriously from its inception.[14] However, comedy had its own Muse: Thalia.

Aristotle taught that comedy was generally positive for society, since it brings forth happiness, which for Aristotle was the ideal state, the final goal in any activity. For Aristotle, a comedy did not need to involve sexual humor. A comedy is about the fortunate rise of a sympathetic character. Aristotle divides comedy into three categories or subgenres: farce, romantic comedy, and satire. On the contrary, Plato taught that comedy is a destruction to the self. He believed that it produces an emotion that overrides rational self-control and learning. In The Republic, he says that the guardians of the state should avoid laughter, "for ordinarily when one abandons himself to violent laughter, his condition provokes a violent reaction." Plato says comedy should be tightly controlled if one wants to achieve the ideal state.

Also in Poetics, Aristotle defined comedy as one of the original four genres of literature. The other three genres are tragedy, epic poetry, and lyric poetry. Literature, in general, is defined by Aristotle as a mimesis, or imitation of life. Comedy is the third form of literature, being the most divorced from a true mimesis. Tragedy is the truest mimesis, followed by epic poetry, comedy, and lyric poetry. The genre of comedy is defined by a certain pattern according to Aristotle's definition. Comedies begin with low or base characters seeking insignificant aims and end with some accomplishment of the aims which either lightens the initial baseness or reveals the insignificance of the aims.

Early Renaissance forms of comedy

The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia [diˈviːna komˈmɛːdja]) is a long narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed in 1320, a year before his death in 1321. It is widely considered to be the preeminent work in Italian literature[15] and one of the greatest works of world literature.[16] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[17] It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

The narrative describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise or Heaven,[18] while allegorically the poem represents the soul's journey towards God.[19] Dante draws on medieval Christian theology and philosophy, especially Thomistic philosophy and the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas.[20] Consequently, the Divine Comedy has been called "the Summa in verse".[21] In Dante's work, Virgil is presented as human reason and Beatrice is presented as divine knowledge.[22]

The work was originally simply titled Comedia (so also in the first printed edition, published in 1472). The adjective Divina was added by Giovanni Boccaccio, and the first edition to name the poem Divina Comedia in the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce,[23] published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

The Divine Comedy is composed of 14,233 lines that are divided into three cantiche (singular cantica) – Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) – each consisting of 33 cantos (Italian plural canti). An initial canto, serving as an introduction to the poem and generally considered to be part of the first cantica, brings the total number of cantos to 100. It is generally accepted, however, that the first two cantos serve as a unitary prologue to the entire epic, and that the opening two cantos of each cantica serve as prologues to each of the three cantiche.[24][25][26]

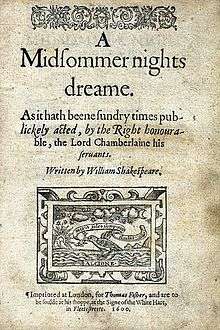

Commedia dell'arte and Shakespearean, Elizabethan comedy

"Comedy", in its Elizabethan usage, had a very different meaning from modern comedy. A Shakespearean comedy is one that has a happy ending, usually involving marriages between the unmarried characters, and a tone and style that is more light-hearted than Shakespeare's other plays.[27]

The Punch and Judy show has roots in the 16th-century Italian commedia dell'arte. The figure of Punch derives from the Neapolitan stock character of Pulcinella.[28] The figure who later became Mr. Punch made his first recorded appearance in England in 1662.[29] Punch and Judy are performed in the spirit of outrageous comedy — often provoking shocked laughter — and are dominated by the anarchic clowning of Mr. Punch.[30] Appearing at a significant period in British history, professor Glyn Edwards states: "[Pulcinella] went down particularly well with Restoration British audiences, fun-starved after years of Puritanism. We soon changed Punch's name, transformed him from a marionette to a hand puppet, and he became, really, a spirit of Britain — a subversive maverick who defies authority, a kind of puppet equivalent to our political cartoons."[29]

19th to early 20th century

In early 19th century England, pantomime acquired its present form which includes slapstick comedy and featured the first mainstream clown Joseph Grimaldi, while comedy routines also featured heavily in British music hall theatre which became popular in the 1850s.[31] British comedians who honed their skills in music hall sketches include Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel and Dan Leno.[32] English music hall comedian and theatre impresario Fred Karno developed a form of sketch comedy without dialogue in the 1890s, and Chaplin and Laurel were among the comedians who worked for his company.[32] Karno was a pioneer of slapstick, and in his biography, Laurel stated, "Fred Karno didn't teach Charlie [Chaplin] and me all we know about comedy. He just taught us most of it".[33] Film producer Hal Roach stated: "Fred Karno is not only a genius, he is the man who originated slapstick comedy. We in Hollywood owe much to him."[34] American vaudeville emerged in the 1880s and remained popular until the 1930s, and featured comedians such as W. C. Fields, Buster Keaton and the Marx Brothers.

20th century theatre and art

Surreal humour (also known as 'absurdist humour'), or 'surreal comedy', is a form of humour predicated on deliberate violations of causal reasoning, producing events and behaviours that are obviously illogical. Constructions of surreal humour tend to involve bizarre juxtapositions, incongruity, non-sequiturs, irrational or absurd situations and expressions of nonsense.[35] The humour arises from a subversion of audience's expectations, so that amusement is founded on unpredictability, separate from a logical analysis of the situation. The humour derived gets its appeal from the ridiculousness and unlikeliness of the situation. The genre has roots in Surrealism in the arts.[35]

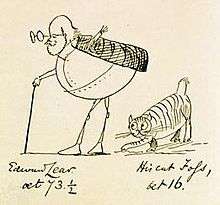

Surreal humour is the effect of illogic and absurdity being used for humorous effect. Under such premises, people can identify precursors and early examples of surreal humour at least since the 19th century, such as Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, which both use illogic and absurdity (hookah-smoking caterpillars, croquet matches using live flamingos as mallets, etc.) for humorous effect. Many of Edward Lear's children stories and poems contain nonsense and are basically surreal in approach. For example, The Story of the Four Little Children Who Went Round the World (1871) is filled with contradictory statements and odd images intended to provoke amusement, such as the following:

After a time they saw some land at a distance; and when they came to it, they found it was an island made of water quite surrounded by earth. Besides that, it was bordered by evanescent isthmuses with a great Gulf-stream running about all over it, so that it was perfectly beautiful, and contained only a single tree, 503 feet high.[36]

In the early 20th century, several avant-garde movements, including the dadaists, surrealists, and futurists, began to argue for an art that was random, jarring and illogical.[37] The goals of these movements were in some sense serious, and they were committed to undermining the solemnity and self-satisfaction of the contemporary artistic establishment. As a result, much of their art was intentionally amusing.

A famous example is Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917), an inverted urinal signed "R. Mutt". This became one of the most famous and influential pieces of art in history, and one of the earliest examples of the found object movement. It is also a joke, relying on the inversion of the item's function as expressed by its title as well as its incongruous presence in an art exhibition.[38]

20th century film, records, radio, and television

.jpg)

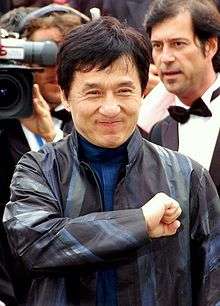

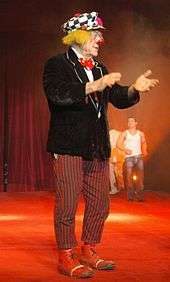

The advent of cinema in the late 19th century, and later radio and television in the 20th century broadened the access of comedians to the general public. Charlie Chaplin, through silent film, became one of the best-known faces on Earth. The silent tradition lived on well into the 20th century through mime artists like Marcel Marceau, and the physical comedy of artists like Rowan Atkinson as Mr. Bean. The tradition of the circus clown also continued, with such as Bozo the Clown in the United States and Oleg Popov in Russia. Radio provided new possibilities — with Britain producing the influential surreal humour of the Goon Show after the Second World War. The Goons' influence spread to the American radio and recording troupe the Firesign Theatre. American cinema has produced a great number of globally renowned comedy artists, from Laurel and Hardy, the Three Stooges, Abbott and Costello, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, as well as Bob Hope during the mid-20th century, to performers like George Carlin, Robin Williams, and Eddie Murphy at the end of the century. Hollywood attracted many international talents like the British comics Peter Sellers, Dudley Moore and Sacha Baron Cohen, Canadian comics Dan Aykroyd, Jim Carrey, and Mike Myers, and the Australian comedian Paul Hogan, famous for Crocodile Dundee. Other centres of creative comic activity have been the cinema of Hong Kong, Bollywood, and French farce.

American television has also been an influential force in world comedy: with American series like M*A*S*H, Seinfeld and The Simpsons achieving large followings around the world. British television comedy also remains influential, with quintessential works including Fawlty Towers, Monty Python, Dad's Army, Blackadder, and The Office. Australian satirist Barry Humphries, whose comic creations include the housewife and "gigastar" Dame Edna Everage, for his delivery of Dadaist and absurdist humour to millions, was described by biographer Anne Pender in 2010 as not only "the most significant theatrical figure of our time ... [but] the most significant comedian to emerge since Charlie Chaplin".[39]

Non-Western history of comedy

Classical Sanskrit Dramas, Plays, and Epics of Ancient India

By 200 BC,[40] in ancient Sanskrit drama, Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra defined humour (hāsyam) as one of the nine nava rasas, or principle rasas (emotional responses), which can be inspired in the audience by bhavas, the imitations of emotions that the actors perform. Each rasa was associated with a specific bhavas portrayed on stage. In the case of humour, it was associated with mirth (hasya).

Studies on comic theory

The phenomena connected with laughter and that which provokes it have been carefully investigated by psychologists. They agree the predominant characteristics are incongruity or contrast in the object and shock or emotional seizure on the part of the subject. It has also been held that the feeling of superiority is an essential factor: thus Thomas Hobbes speaks of laughter as a "sudden glory". Modern investigators have paid much attention to the origin both of laughter and of smiling, as well as the development of the "play instinct" and its emotional expression.

George Meredith said that "One excellent test of the civilization of a country ... I take to be the flourishing of the Comic idea and Comedy, and the test of true Comedy is that it shall awaken thoughtful laughter." Laughter is said to be the cure for being sick. Studies show that people who laugh more often get sick less.[41][42]

American literary theorist Kenneth Burke writes that the "comic frame" in rhetoric is "neither wholly euphemistic, nor wholly debunking—hence it provides the charitable attitude towards people that is required for purposes of persuasion and co-operation, but at the same time maintains our shrewdness concerning the simplicities of ‘cashing in.’" [43] The purpose of the comic frame is to satirize a given circumstance and promote change by doing so. The comic frame makes fun of situations and people, while simultaneously provoking thought.[44] The comic frame does not aim to vilify in its analysis, but rather, rebuke the stupidity and foolery of those involved in the circumstances.[45] For example, on The Daily Show, Jon Stewart uses the "comic frame" to intervene in political arguments, often offering crude humor in sudden contrast to serious news. In a segment on President Obama's trip to China Stewart remarks on America's debt to the Chinese government while also having a weak relationship with the country. After depicting this dismal situation, Stewart shifts to speak directly to President Obama, calling upon him to "shine that turd up."[46] For Stewart and his audience, introducing coarse language into what is otherwise a serious commentary on the state of foreign relations serves to frame the segment comically, creating a serious tone underlying the comedic agenda presented by Stewart.

Forms

Comedy may be divided into multiple genres based on the source of humor, the method of delivery, and the context in which it is delivered. The different forms of comedy often overlap, and most comedy can fit into multiple genres. Some of the subgenres of comedy are farce, comedy of manners, burlesque, and satire.

Some comedy apes certain cultural forms: for instance, parody and satire often imitate the conventions of the genre they are parodying or satirizing. For example, in the United States, parodies of newspapers and television news include The Onion, and The Colbert Report; in Australia, shows such as Kath & Kim, Utopia, and Shaun Micallef's Mad As Hell perform the same role.

Self-deprecation is a technique of comedy used by many comedians who focus on their misfortunes and foibles in order to entertain.

Performing arts

| Performing arts |

|---|

Historical forms

- Ancient Greek comedy, as practiced by Aristophanes and Menander

- Ancient Roman comedy, as practiced by Plautus and Terence

- Burlesque, from Music hall and Vaudeville to Performance art

- Citizen comedy, as practiced by Thomas Dekker, Thomas Middleton and Ben Jonson

- Clowns such as Richard Tarlton, William Kempe, and Robert Armin

- Comedy of humours, as practiced by Ben Jonson and George Chapman

- Comedy of intrigue, as practiced by Niccolò Machiavelli and Lope de Vega

- Comedy of manners, as practiced by Molière, William Wycherley and William Congreve

- Comedy of menace, as practiced by David Campton and Harold Pinter

- comédie larmoyante or 'tearful comedy', as practiced by Pierre-Claude Nivelle de La Chaussée and Louis-Sébastien Mercier

- Commedia dell'arte, as practiced in the twentieth century by Dario Fo, Vsevolod Meyerhold, and Jacques Copeau

- Farce, from Georges Feydeau to Joe Orton and Alan Ayckbourn

- Jester

- Laughing comedy, as practiced by Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan

- Restoration comedy, as practiced by George Etherege, Aphra Behn and John Vanbrugh

- Sentimental comedy, as practiced by Colley Cibber and Richard Steele

- Shakespearean comedy, as practiced by William Shakespeare

- Stand-up comedy

- Dadaist and Surrealist performance, usually in cabaret form

- Theatre of the Absurd, used by some critics to describe Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Jean Genet and Eugène Ionesco[47]

- Sketch comedy

Plays

- Comic theatre

- Musical comedy and palace

Opera

Improvisational comedy

- Improvisational theatre

- Bouffon comedy

- Clowns

Jokes

- One-liner joke

- Blonde jokes

- Shaggy-dog story

- Paddy Irishman joke

- Polish jokes

- Light bulb jokes

Stand-up comedy

Stand-up comedy is a mode of comic performance in which the performer addresses the audience directly, usually speaking in their own person rather than as a dramatic character.

Events and awards

- American Comedy Awards

- British Comedy Awards

- Canadian Comedy Awards

- Cat Laughs Comedy Festival

- The Comedy Festival, Aspen, Colorado, formerly the HBO Comedy Arts Festival

- Edinburgh Festival Fringe

- Edinburgh Comedy Festival

- Halifax Comedy Festival

- Just for Laughs festival, Montreal

- Leicester Comedy Festival

- Mark Twain Prize for American Humor

- Melbourne International Comedy Festival

- New Zealand International Comedy Festival

- New York Underground Comedy Festival

- HK International Comedy Festival

List of comedians

- List of stand-up comedians

- List of musical comedians

- List of Australian comedians

- List of British comedians

- List of Canadian comedians

- List of Filipino comedians

- List of Finnish comedians

- List of German language comedians

- List of Indian comedians

- List of Italian comedians

- List of Mexican comedians

- List of Puerto Rican comedians

Mass media

| Literature |

|---|

|

| Major forms |

| Genres |

| Media |

| Techniques |

| History and lists |

| Discussion |

|

|

Literature

Film

- Comedy film

- Anarchic comedy film

- Gross-out film

- Parody film

- Romantic comedy

- Screwball comedy film

- Slapstick film

Audio recording

Television and radio

- Television comedy

- Situation comedy

- Radio comedy

Comedy networks

- British sitcom

- British comedy

- Comedy Central – A television channel devoted strictly to comedy

- Comedy Nights with Kapil – An Indian television program

- German television comedy

- List of British TV shows remade for the American market

- Paramount Comedy (Spain)

- Paramount Comedy 1 and 2.

- TBS (TV network)

- The Comedy Channel (Australia)

- The Comedy Channel (UK)

- The Comedy Channel (United States) – merged into Comedy Central.

- HA! – merged into Comedy Central

- The Comedy Network, a Canadian TV channel.

- Gold

- Sky Comedy

See also

Footnotes

- Henderson, J. (1993) Comic Hero versus Political Elite pp. 307–19 in Sommerstein, A.H.; S. Halliwell; J. Henderson; B. Zimmerman, eds. (1993). Tragedy, Comedy and the Polis. Bari: Levante Editori.

- (Anatomy of Criticism, 1957)

- Marteinson, 2006

- "The old derivation from kome "village" is not now regarded."

- Cornford (1934)

- Oxford English Dictionary

- McKeon, Richard. The Basic Works Of Aristotle, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001, p. 1459.

- Webber, Edwin J. (January 1958). "Comedy as Satire in Hispano-Arabic Spain". Hispanic Review. 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2307/470561. JSTOR 470561.

- Herman Braet, Guido Latré, Werner Verbeke (2003) Risus mediaevalis: laughter in medieval literature and art p.1 quotation:

The deliberate use by Menard of the term 'le rire' rather than 'l'humour' reflects accurately the current evidency to incorporate all instances of the comic in the analysis, while the classification in genres and fields such as grotesque, humour and even irony or satire always poses problems. The terms humour and laughter are therefore pragmatically used in recent historiography to cover the entire spectrum.

- Ménard, Philippe (1988) Le rire et le sourire au Moyen Age dans la littérature et les arts. Essai de problématique in Bouché, T. and Charpentier H. (eds., 1988) Le rire au Moyen Âge, Actes du colloque international de Bordeaux, pp. 7–30

- Aristophanes (1996) Lysistrata, Introduction, p.ix, published by Nick Hern Books

- Reckford, Kenneth J. (1987)Aristophanes' Old-and-new Comedy: Six essays in perspective p.105

- Cornford, F.M. (1934) The Origin of Attic Comedy pp.3-4 quotation:

That Comedy sprang up and took shape in connection with Dionysiac or Phallic ritual has never been doubted.

- "Aristotle, Poetics, lines beginning at 1449a". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- For example, Encyclopedia Americana, 2006, Vol. 30. p. 605: "the greatest single work of Italian literature;" John Julius Norwich, The Italians: History, Art, and the Genius of a People, Abrams, 1983, p. 27: "his tremendous poem, still after six and a half centuries the supreme work of Italian literature, remains – after the legacy of ancient Rome – the grandest single element in the Italian heritage;" and Robert Reinhold Ergang, The Renaissance, Van Nostrand, 1967, p. 103: "Many literary historians regard the Divine Comedy as the greatest work of Italian literature. In world literature, it is ranked as an epic poem of the highest order."

- Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon. See also Western canon for other "canons" that include the Divine Comedy.

- See Lepschy, Laura; Lepschy, Giulio (1977). The Italian Language Today. or any other history of Italian language.

- Peter E. Bondanella, The Inferno, Introduction, p. xliii, Barnes & Noble Classics, 2003, ISBN 1-59308-051-4: "the key fiction of the Divine Comedy is that the poem is true."

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on page 19.

- Charles Allen Dinsmore, The Teachings of Dante, Ayer Publishing, 1970, p. 38, ISBN 0-8369-5521-8.

- The Fordham Monthly Fordham University, Vol. XL, Dec. 1921, p. 76

- Approaches to teaching Dante's Divine comedy. Slade, Carole., Cecchetti, Giovanni, 1922–1998. New York: Modern Language Association of America. 1982. ISBN 978-0-87352-478-0. OCLC 7671339.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ronnie H. Terpening, Lodovico Dolce, Renaissance Man of Letters (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 1997), p. 166.

- Dante The Inferno A Verse Translation by Professor Robert and Jean Hollander p. 43

- Epist. XIII 43 to 48

- Wilkins E.H The Prologue to the Divine Comedy Annual Report of the Dante Society, pp. 1–7.

- Regan, Richard. "Shakespearean comedy"

- Wheeler, R. Mortimer (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 648–649.

- "Punch and Judy around the world". The Telegraph. 11 June 2015.

- "Mr Punch celebrates 350 years of puppet anarchy". BBC. 11 June 2015.

- Jeffrey Richards (2014). "The Golden Age of Pantomime: Slapstick, Spectacle and Subversion in Victorian England". I.B.Tauris,

- McCabe, John. "Comedy World of Stan Laurel". p. 143. London: Robson Books, 2005, First edition 1975

- Burton, Alan (2000). Pimple, pranks & pratfalls: British film comedy before 1930. Flicks Books. p. 51.

- J. P. Gallagher (1971). "Fred Karno: master of mirth and tears". p. 165. Hale.

- Stockwell, Peter (2016-11-01). The Language of Surrealism. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-137-39219-0.

- Lear, Edward (2004-10-08). Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany, and Alphabets.

- Buelens, Geert; Hendrix, Harald; Jansen, Monica, eds. (2012). The History of Futurism: The Precursors, Protagonists, and Legacies. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7387-9.

- Gayford, Martin (16 February 2008). "Duchamp's Fountain: The practical joke that launched an artistic revolution". The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Meacham, Steve (2010-09-15). "Absurd moments: in the frocks of the dame". Brisbanetimes.com.au. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- Robert Barton, Annie McGregor (2014-01-03). Theatre in Your Life. CengageBrain. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-285-46348-3.

- "An impolite interview with Lenny Bruce". The Realist (15): 3. February 1960. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- Meredith, George (1987). "Essay on Comedy, Comic Spirit". Encyclopedia of the Self, by Mark Zimmerman. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- "The Comic Frame". newantichoicerhetoric.web.unc.edu.

- "Standing Up for Comedy: Kenneth Burke and The Office – KB Journal". www.kbjournal.org.

- "History – School of Humanities and Sciences". www.ithaca.edu. Ithaca College.

- Trischa Goodnow Knapp (2011). The Daily Show and Rhetoric: Arguments, Issues, and Strategies. p. 327. Lexington Books, 2011

- This list was compiled with reference to The Cambridge Guide to Theatre (1998).

Notations

- Aristotle. Poetics.

- Buckham, Philip Wentworth (1827). Theatre of the Greeks. J. Smith.

The Theatre of the Greeks.

- Marteinson, Peter (2006). On the Problem of the Comic: A Philosophical Study on the Origins of Laughter. Ottawa: Legas Press. http://french.chass.utoronto.ca/as-sa/editors/origins.html

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace

- Dithyramb, Tragedy, and Comedy , 1927.

- The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, 1946.

- The Dramatic Festivals of Athens, 1953.

- Raskin, Victor (1985). The Semantic Mechanisms of Humor. Springer. ISBN 978-90-277-1821-1.

- Riu, Xavier (1999). "Dionysism and Comedy". Bryn Mawr Classical Review.

- Sourvinou-Inwood, Christiane (2003). Tragedy and Athenian Religion. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0400-2.

- Trypanis, C.A. (1981). Greek Poetry from Homer to Seferis. University of Chicago Press.

- Wiles, David (1991). The Masked Menander: Sign and Meaning in Greek and Roman Performance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40135-7.

Further reading

- Comedy at Curlie

- A Vocabulary for Comedy (definitions are taken from Harmon, William & C. Hugh Holman. A Handbook to Literature. 7th ed.)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Comedy. |

_Mytilene_3cAD.jpg)