Pulcinella

Pulcinella (Italian pronunciation: [pultʃiˈnɛlla], Neapolitan: "Polecenella") is a classical character that originated in commedia dell'arte of the 17th century and became a stock character in Neapolitan puppetry. Pulcinella's versatility in status and attitude has captivated audiences worldwide and kept the character popular in countless forms since his introduction to commedia dell'arte by Silvio Fiorillo in 1620.[1]

.jpg)

Characteristics

Pulcinella was raised by two "fathers", Maccus and Bucco. Maccus is described as being witty, sarcastic, rude, and cruel, while Bucco is a nervous thief who is as silly as he is full of himself.[2] This duality manifested itself in both the way Pulcinella is shaped and the way he acts. Physically, the characteristics he inherited from his fathers attributed to his top-heavy, chicken-like shape. He inherited his humpback, his large, crooked nose, and his gangly legs from Maccus. His potbelly, large cheeks, and gigantic mouth come from Bucco.[3]

Due to this duality of paternal lineage, Pulcinella can be portrayed as either a servant and master, depending on the scenario. "Upper" Pulcinella is more like Bucco, with a scheming nature, an aggressive sensuality, and great intelligence. "Lower" Pulcinella, however, favors Maccus, and is described by Pierre Louis Duchartre as being "a dull and coarse bumpkin."[4] This juxtaposition of proud, cunning thief from the upper class and loud, crass pervert from the servant class is one that is key to understanding Pulcinella's behaviors.

Pulcinella is a dualistic character: he either plays dumb, though he is very much aware of the situation, or he acts as though he is the most intelligent and competent, despite being woefully ignorant.[6] He is incessantly trying to rise above his station, though he does not intend to work for it. He is a social chameleon, who tries to get those below him to think highly of him, but is sure to appease those in positions of power. Pulcinella's closing couplet translates to "I am Prince of everything, Lord of land and main. Except for my public whose faithful servant I remain."[7] However, because his world is often that of a servant, he has no real investment in preserving the socio-political world of his master.[8] He is always on the side of the winner, though he often does not decide this until after they have won. No matter his initial intent, Pulcinella always manages to win. If something ends poorly, another thing is successful. If he is put out in a sense, he is rewarded in another.[9] This often accidental triumph is his normal. Another important characteristic of Pulcinella is that he fears nothing. He does not worry about consequences as he will be victorious no matter what. It is said that he is so wonderful to watch because he does what audience members would do were they not afraid of the consequences.[10]

Pulcinella is the ultimate self-preservationist, looking out for himself in most every situation, yet he still manages to sort out the affairs of everyone around him. Antonio Fava, a world-renowned maskmaker and Maestro of Commedia dell'arte, is particularly fond of the character in both performance and study due to his influence and continuity throughout history. Fava explained that "Pulcinella, a man without dignity, is nevertheless indispensable to us all: without [him] ... none of his countless 'bosses' could ever escape from the awkward tangle of troubles in which they find themselves. Pulcinella is everyone's saviour, saved by no one."[12] This accidental helpfulness is key to his success. He goes out of his way to avoid responsibility, yet always ends up with more of it than he bargained for.

His movements are broad and laborious, allowing him to aggressively emphasize his speech and simultaneously exhausting him. He will also get excited about something and move very quickly and deliberately, leaving him with no choice but to halt the action and catch his breath.[13] He is to be thought of as a rebellious delinquent in the body of an old man.[13]

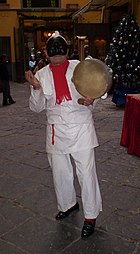

Mask

Traditionally made of leather, Pulcinella's mask is either black or dark brown, to imply weathering from the sun. His nose varies, but is always the most prominent feature of the mask by far. It can be long and curved, hooking over the mouth, or it can be shorter, with a more bulbous bridge. But either way, the nose is to resemble a bird's beak. There is often a wart somewhere on the mask, typically on the forehead or nose.[14] Furrowed eyebrows and deep wrinkles are also important, though there is room for artistic interpretation there. He can have a protruding brow ridge, knitted brows, a furrowed brow, or simply raised eyebrows. It is simply important that they are deeply wrinkled and prominent enough to match the exaggerated style of commedia dell'arte masks. The mask used to feature a bushy black mustache or beard, but this was mostly abandoned through the 17th century.[15]

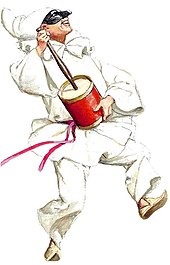

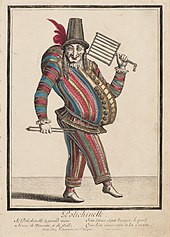

Costume and props

Pulcinella is most often portrayed in a baggy, white ensemble consisting of a long-sleeved, loose-fitting blouse with buttons down the front. He paired this with wide-legged trousers, the whole outfit complemented by a belt of sorts that cinches below the belly. This gives him a place to hold props while emphasizing his pot belly.[14] A hat is always worn, though the style can vary. Typically, it can either be a skull cap, or hat with turn-up brim,[16] a soft conical hat whose point lays down, or a rigid sugar-loaf hat. The sugar loaf hat gained popularity in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Either hat is white.[17]

Pulcinella has two main props: The first is a cudgel, which is a relatively short stick often used primarily as a weapon. He calls this his "staff of credit." His other prop is a coin purse that's traditionally attached to his belt so as to stay close to the body.[15]

Etymology

A plausible theory derives his name from the diminutive (or combination with pollastrello "rooster")[18]) of Italian pulcino ("chick"), on account of his long beaklike nose, as theorized by music historian Francesco Saverio Quadrio, or due to the squeaky nasal voice and "timorous impotence" in its demeanor, according to Giuseppe (Joseph) Baretti.[19]

According to another version, Pulcinella derived from the name of Puccio d'Aniello, a peasant of Acerra, who was portrayed in a famous picture attributed to Annibale Carracci, and was characterized by a long nose.[19] It has also been suggested that the figure is a caricature of a sufferer of acromegaly.[20]

Variants

Many regional variants of Pulcinella were developed as the character diffused across Europe. From its east to west coasts, Europeans strongly identified with the tired, witty "everyman" that Pulcinella represented. In many later adaptations, Pulcinella was portrayed as a puppet, as commedia dell'arte-style theatre did not continue to be popular throughout all of the continent over time. He was said to evolve into "Mr. Punch" in England. The key half of Punch and Judy, he is recognized as one of the most important British icons in history.[21]

The first recorded show to have involved the Punch-style marionette was performed in England in May 1662, outside of London in Covent Garden, by Bologna-born puppeteer Pietro Gimonde, also known as Signor Bologna.[21] This marionette was named Punchinello, later evolving into Punch, and finally becoming wholly British with his transformation into Mr. Punch. The British Punch is far more childlike and violent than Pulcinella, but is renowned for being just as funny.[22] Always seen with cudgel in hand, Punch has a more menacing character than his Italian counterpart. In many performances, he murders his wife and child, as well as the Devil. In 1851, Henry Mayhew wrote of one performer who described the character's enduring appeal: "Like the rest of the world, he has got bad morals, but very few of them."[23]

In Germany, this kind of Pulcinella-based puppet character came to be known as Kasper. Kasper is a cunning servant who solves the problems of all the masters he serves.[24] This character became wildly popular throughout Europe. He was less extreme than Mr. Punch, but offered the same kind of slapstick puppetry that audiences loved. In the Netherlands, he is known as Jan Klaassen. In Denmark he is Mester Jakel. In Romania, he is Vasilache. In Hungary he is Paprika Jancsi (or Paprikajancsi) and in the 20th century Vitéz László, and in France he remained Polichinelle.

Russian composer Igor Stravinsky was commissioned to compose two different ballets for the Ballets Russes that were inspired by variations of this character. Stravinsky's ballets were entitled Petrushka (1911), based on Russian 19th-century puppetry traditions celebrated at Shrovetide, and Pulcinella (1920), based on 17th-century Italian music (thought to be by Pergolesi) associated with a commedia dell'arte version.

Miscellanea

- Pulcinella Awards mascot – Pulcinella is the mascot of the Pulcinella Awards, annual awards for excellence in animation, presented at the Cartoons on the Bay Festival in Positano, Italy.

- Open secret – In various European languages, including at least Italian,[25] French,[26] Spanish,[27] Polish,[28] Russian,[29] and Portuguese,[30] a "Pulcinella's secret" or a "Polichinelo's secret" is an open secret.

Italian psychoanalyst and philosopher Emilio Mordini has discussed Pulcinella secrets[31], saying that they help people to retain their sanity[32] in contexts where secrets are impossible (e.g., small villages, today's online world). Mordini argues that Pulcinella secrets "are not really secret in the sense that they are unknown or unknowable, but because they are labeled as secret".[33]

References

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia Dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. London, England: Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-0415047708.

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis (1966). The Italian Comedy. United States of America: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 208. ISBN 978-0486216799.

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis (1966). The Italian Comedy. United States of America: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 209. ISBN 978-0486216799.

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis (1966). The Italian Comedy. United States of America: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 212. ISBN 978-0486216799.

- Bonnart, Nicolas (1680–1690). "DAC Collection Object Information - "Polichinelle"". DAC-Collection.Wesleyan.edu. Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. London, England: Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group. p. 141. ISBN 978-0415047708.

- Oreglia, Giacomo (1968). The Commedia dell'Arte. Translated by Edwards, Lovett F. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 94. ISBN 978-0809005451.

- McGhee, Scott (2015). Chaffee, Judith; Crick, Oliver (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Commedia Dell'Arte. New York, New York: Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Frances Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415745062.

- Fava, Antonio (2013). "Pulcinella Character and Mask Description". AntonioFava.com. Antonio Fava. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Grantham, Barry (2000). Playing Commedia. United Kingdom: Nick Hern Books. p. 208. ISBN 978-1854594662.

- "Pulcinella In 1700 By Maurice Sand 1860 Engraving Stock Illustration". Gety Images. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- Fava, Antonio (December 5, 2014). Chaffee, Judith; Crick, Oliver (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell'Arte. Translated by Perlman, Mace (1st ed.). New York, New York: Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group. p. 111. ISBN 978-0415745062.

- Grantham, Barry (2000). Playing Commedia. United Kingdom: Nick Hern Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-1854594662.

- Grantham, Barry (January 9, 2000). Playing Commedia. United Kingdom: Nick Hern Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-1854594662.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia Dell'Arte: An Actor's Handbook. London, England: Routledge, and imprint of Taylor & Francis Group. p. 140. ISBN 978-0415047708.

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis (1966). The Italian Comedy. New York, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 220. ISBN 978-0486216799.

- Grantham, Barry (October 27, 2000). Playing Commedia. United Kingdom: Nick Hern Books. p. 210. ISBN 978-1854594662.

- Fava, Antonio (2013). "I Servi (The Servants) - Pulcinella". AntonioFava.com. Antonio Fava. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Wheeler, R. Mortimer (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 648–649.

- "UK | England | Derbyshire | Mr Punch's 'bad mood' syndrome". BBC News. 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "That's the Way to Do it! A History of Punch and Judy". VAM.ac.uk. Victoria and Albert Museum. 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Fava, Antonio (December 5, 2014). Chaffee, Judith; Crick, Oliver (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell'Arte. Translated by Perlman, Mace. New York, New York: Routledge, an imprint of Tayor & Francis Group. p. 109. ISBN 978-0415745062.

- Gatrell, Vic. City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth Century London, Walker & Company, 2006, pg. 200-201

- "Kasperletheatre Puppets, Germany". ObjectLessons.org. Islington Education Library Service. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "pulcinella translation from Collins Unabridged Italian-English dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "polichinelle translation from Collins French-English dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "secreto de Polichinela translation from Collins Unabridged Spanish-English dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- "poliszynel, Słownik Wyrazów Obcych i zwrotów obcojęzycznych Władysława Kopalinskiego". www.slownik-online.pl. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Справочник по фразеологии". gramota.ru. Retrieved 2017-04-15.

- "Polichinelo". www.ciberduvidas.com. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- Mordini, Emilio (2011). "Pulcinella Secrets". Bioethics. 25 (9): ii–iii. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01938.x. PMID 21988143.

- Cole, Tim (2015). Digital Enlightenment Now!: How the Internet is making us better and smarter and in the process changing just about everything around us!. Norderstedt, DE: BoD – Books on Demand. p. 280. ISBN 9783738697667.

- "Pulcinella revisited". 2015. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

External links

- The Commedia dell'Arte Homepage