Robert Armin

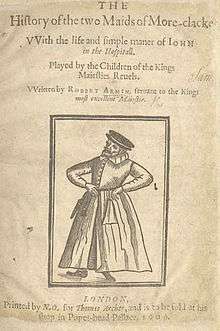

Robert Armin (c. 1568 – 1615) was an English actor, a member of the Lord Chamberlain's Men. He became the leading comedy actor with the troupe associated with William Shakespeare following the departure of Will Kempe around 1600. Also a popular comic author, he wrote a comedy, The History of the Two Maids of More-clacke, as well as Foole upon Foole, A Nest of Ninnies (1608) and The Italian Taylor and his Boy.

Armin changed the part of the clown or fool from the rustic servingman turned comedian to that of a high-comedy domestic wit.

Early life

- "…the clown is wise because he plays the fool for money, while others have to pay for the same privilege." – Leslie Hotson in Shakespeare's Motley

Armin was one of three children born to John Armyn II of King's Lynn, a successful tailor and friend to John Lonyson, a goldsmith also of King's Lynn. His brother, John Armyn III, was a merchant tailor in London. Armin did not take up his father's craft; instead, his father apprenticed him to Lonyson in the Goldsmiths' Company in 1581. Lonyson was the Master of Works at the Royal Mint in the Tower of London, a position of great responsibility. The arrangement moved Armin to a life and a social circle quite different from what he might have expected as a Norfolk tailor. Lonyson died in 1582, and the apprenticeship was transferred to another master. According to a tale preserved in Tarlton's Jests, Armin came to the attention of the Queen's famous jester Richard Tarlton. In the course of his duties, the story contends, Armin was sent to collect money from a lodger at Tarlton's inn. Frustrated by the man's refusal to pay, Armin wrote verses in chalk on the wall; Tarlton noticed and, approving their wit, wrote an answer in which he expressed a desire to take Armin as his apprentice. Though not corroborated, this anecdote is far from the least plausible in Tarlton's Jests. Influenced by Tarlton or not, Armin already had a literary reputation before he finished his apprenticeship in 1592. In 1590, his name is affixed to the preface of a religious tract, A Brief Resolution of the Right Religion. Two years later, both Thomas Nashe (in Strange News) and Gabriel Harvey (in Pierce's Supererogation) mention him as a writer of ballads; none of his work in this vein, however, is known to have survived.

The Chandos company

At some point in the 1590s, Armin joined a company of players patronised by William Brydges, 4th Baron Chandos. With this company, about which little is known, he is presumed to have travelled from the western Midlands to East Anglia. The nature of his work for the company may be estimated from his parts in The History of the Two Maids of More-clacke. The preface to the 1609 quarto indicates that he played Blue John, a clown in the vein of Tarlton and Kempe; he also seems to have doubled in the role of Tutch, a witty fool of the type he later played in London. The late quarto is associated with a revival by the King's Revels Children, a short-lived troupe of boy players led by Nathan Field, but it was almost certainly written around 1597.

Little else is known precisely of Armin's time with Chandos's Men. A dedication to his patron's widow in 1604 suggests some personal acquaintance with the Brydges family; on the other hand, a reference in another work suggests he may have spent some time, like Kempe, as a solo performer. The pair of books Armin published around the turn of the century demonstrate a performer with an interest in his craft. Fool Upon Fool (1600, 1605; reissued in 1608 as A Nest of Ninnies), offers the wit of assorted natural fools, some of whom Armin knew personally. The same year he published Quips upon Questions, a collection of seemingly extemporaneous dialogues with his marotte, named by him Signor Truncheon. In this he demonstrates his style; instead of having a conversation with the audience, as Tarlton did, and entering into a battle of wits, he jests using multiple personas, improvised song, or by commenting on a person or event. Rather than exchanging words, he gave words freely. Armin reported in that work that on either Tuesday 25 December 1599, or Tuesday 1 January 1600, he would be travelling to Hackney to wait on his "right honourable good lord". This was possibly Baron Chandos, who may have been visiting Edward la Zouche, 11th Baron Zouche over the holidays, or more likely Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford who lived in Hackney.[1][2]

The first editions of these two books were credited to "Clonnico de Curtanio Snuffe"—that is, to the "Clown of the Curtain". The 1605 edition changes "Curtain" to "Mundo" (that is, Globe); only in 1608 was he credited by name, though the earlier title pages would have sufficed to identify him for Londoners.

Another work of uncertain date (it was published in 1609) is The Italian Tailor and his Boy. A translation of a tale from Gianfrancesco Straparola, the subject matter may reflect his family background of tailors. He was a tailor's son, who paralleled in the Italian tailor's apprentice, and the ruby ring of the play's lore parallels the goldsmith apprentice.

Sutcliffe argues that Armin wrote a pamphlet published in 1599, A Pil to Purge Melancholie, on the grounds that it was published by the same press, mentions a clown with Armin's nickname, and contains verbal echoes of Two Maids of More-clacke.

Lord Chamberlain's Men

The timing of Armin's joining the Chamberlain's Men is as mysterious as its occasion. That it was connected to Kempe's departure has been generally accepted; however, the reasons for that departure are not clear. One traditional view—that the company in general or Shakespeare specifically had begun to tire of Kempe's old-fashioned clowning—is still current, though the main evidence for this view consists of Kempe's departure and the type of comic roles Shakespeare wrote after 1600. Armin played on the Globe stage by August 1600; Wiles theorizes that he may have joined the Chamberlain's Men in 1599, but continued to perform solo pieces at the Curtain; however, he may also have played with the company at the Curtain, while Kempe was still a member.

Armin is generally credited with all the "licensed fools" in the repertory of the Chamberlain's and King's Men: Touchstone in As You Like It, Feste in Twelfth Night, the Fool in King Lear, Lavatch in All's Well That Ends Well, and perhaps Thersites in Troilus and Cressida, the Porter in Macbeth, the Fool in Timon of Athens, and Autolycus in The Winter's Tale. Of these eight, Touchstone is the fool about which there is the most critical discussion. Harold Bloom describes him as "rancidly vicious," and writes that "this more intense rancidity works as a touchstone should, to prove the true gold of Rosalind's spirit". John Palmer disagrees and writes that "he must be either a true cynic or one that affects his cynicism to mask a fundamentally genial spirit". Obviously, as Palmer continues, a true cynic does not belong in Arden, so the clown "must be a thoroughly good fellow at heart". Touchstone affects the front of a malcontented cynic, thus serving as proof of Rosalind's quick wit. When she confronts both Jaques and Touchstone, she exposes their silliness and prevents the fools from making Arden out to be worse than it really is.

Feste was almost certainly written for Armin, as he is a scholar, a singer, and a wit. Feste's purpose is to reveal the foolishness of those around him. Lear's fool differs from both Touchstone and Feste as well as from other clowns of his era. Touchstone and Feste are philosopher-fools; Lear's fool is the natural fool of whom Armin studied and wrote. Armin here had the opportunity to display his studies. The fool speaks the prophecy lines, which he tells—largely ignored—to Lear before disappearing from the play altogether. Lear's fool is hardly around for entertainment purposes; rather, he is present to forward the plot, remain loyal to the king, and perhaps to stall his madness.

Although Armin typically played these intelligent clown roles, it has been suggested by a few scholars that he originated the role of Iago in Othello, on the grounds that Iago sings two drinking songs (most of the songs in Shakespeare's plays from 1600 to 1610 were sung by Armin's characters) and that this was the sole play between As You Like It and Timon of Athens that has no fool or clown for Armin to play.[3][4] An alternative suggestion, though, is that Iago was originally acted by John Lowin, with Armin instead taking the smaller part of Othello's servant.[5][6][7]

In non-Shakespearean roles, he probably played Pasarello in John Marston's The Malcontent; indeed, Marston may have added the part for him when the play was produced by the King's Men. Armin appears in the cast list for Ben Jonson's The Alchemist; he may have played Drugger. He is also presumed to have been the clown in George Wilkins's The Miseries of Enforced Marriage.

He is not named in the cast list for Jonson's Catiline (1611), and other evidence suggests that he retired in 1609 or 1610. The preface to the Two Maids quarto confides, "I would have again enacted John myself, but tempora mutantur in illis, and I cannot do as I would". He was buried in late 1615.

In London, he resided in the parish of St Botolph's Aldgate; three of his children named in the parish register appear to have died before adulthood. Fellow King's Man Augustine Phillips bequeathed him twenty shillings as a "fellow"; John Davies of Hereford wrote Armin a complimentary epigram. His burial is recorded in the Registers of St Botolph's as 30 November 1615.[8]

A new fool

Armin may have played a key role in the development of Shakespearian fools.[9] "If any player breathed," Hotson tells us, "who could explore with Shakespeare the shadows and fitful flashes of the borderland of insanity, that player was Armin". Robert Armin explored every aspect of the clown, from the natural idiot to the philosopher-fool; from serving man to retained jester. In study, writing, and performance, Armin moved the fool from rustic zany to trained motley. His characters—those he wrote and those he acted—absurdly point out the absurdity of what is otherwise called normal. Instead of appealing to the identity of the English commoner by imitating them, he created a new fool, a high-comic jester for whom wisdom is wit and wit is wisdom. When Robert Armin replaced Kemp in the Chamberlain's Men, it was considered the "taming of the clown". Armin's new style of comedy brought into play the "world-wisely fool". This urged Shakespeare to create Feste in his Twelfth Night, who was a philosophical social insurgence. He had a place everywhere, but belonged nowhere. Ken Kesey told an interviewer of this notion of a fool. "That fool of Shakespeare's, the actor Robert Armin, became so popular that finally Shakespeare wrote him out of Henry IV. In a book called A Nest of Ninnies, Armin wrote about the difference between a fool artificial and a fool natural. And the way Armin defines the two is important: the character Jack Oates is a true fool natural. He never stops being a fool to save himself; he never tries to do anything but anger his master, Sir William. A fool artificial is always trying to please; he’s a lackey."[10]

Modern References

The Shakespeare Stealer

Robert Armin is a significant character in Gary Blackwood's historical fiction The Shakespeare Stealer.

Tam Lin

In the 1991 Pamela Dean novel Tam Lin, one of the major characters is Robert Armin (better known as Robin), a Classics and Theater student at a small college in the Midwestern U.S. during the early 1970s who has a surprisingly detailed knowledge of William Shakespeare's life and work.

References

- Bednarz. James P. (2001) Shakespeare and the Poet's War, New York: Columbia UP, p. 267.

- McCrea, Scott (2005), The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question, Westport: Praeger, p. 169.

- Verdi's Shakespeare: Men of the Theater, Garry Wills, p. 88-90

- Shakespeare and the Poet's Life, Gary Schmidgall, p. 157

- Hampton-Reeves, Stuart (2010). Othello. Macmillan International Higher Education. pp. 6, 8.

- Kawai, Shoichiro (1992). "John Lowin as Iago". Shakespeare Studies (Japan). 30: 17–34.

- McMillin, Scott (1987). The Elizabethan Theatre and "The Book of Sir Thomas More. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. p. 63.

- Nungezer, Edwin (1929), "A Dictionary of Actors and of Other Persons Associated with the Public Representation of Plays in England, before 1642", OUP

- History of the Fool

- The Paris Review, "Ken Kesey, The Art of Fiction No. 136 (Interviewed by Robert Faggen)"

Sources

- Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books, 1998.

- Brown, John Russell. The Oxford Illustrated History of Theatre. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. Web.

- Faggen, Robert. Ken Kesey-The Art of Fiction. The Paris Review: Issue 130, Spring 1994.

- Felver, Charles S. "Robert Armin, Shakespeare's Fool: a Biographical Essay." Kent State University Bulletin 49(1) January 1961.

- Gray, Austin. "Robert Armine, the Foole." PMLA 42 (1927), 673–685.

- Hotson, Leslie. Shakespeare’s Motley. New York: Oxford University Press, 1952.

- Lippincott, H. F. "King Lear and the Fools of Armin." Shakespeare Quarterly 26 (1975), 243–253.

- Palmer, John. Comic Characters of Shakespeare. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1953.

- Sutcliffe, Chris. Robert Armin: Apprentice Goldsmith. Notes and Queries (1994) 41(4): 503–504.

- Sutcliffe, Chris. The Canon of Robert Armin's Work: An Addition. Notes and Queries (1996) 43(2): 171–175.

- Wiles, David. Shakespeare's Clown. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Zall, P. M., ed. A Nest of Ninnies and Other English Jestbooks of the Seventeenth Century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1970.