Chillisquaque Creek

Chillisquaque Creek is a tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Montour County and Northumberland County, in Pennsylvania, in the United States. It is approximately 20.2 miles (32.5 km) long and flows through Derry Township, Washingtonville, and Liberty Township in Montour County and East Chillisquaque Township and West Chillisquaque Township in Northumberland County.[1] The watershed of the creek has an area of 112 square miles (290 km2). Agricultural impacts have caused most of the streams in the watershed of the creek (including the main stem) to be impaired. Causes of impairment include sedimentation/siltation and habitat alteration. The average annual discharge of the creek between 1980 and 2014 ranged from 48.2 to 146.0 cubic feet per second (1.36 to 4.13 m3/s). Its watershed mainly consists of rolling agricultural land. The creek's channel flows through rock formations consisting of sandstone and shale. It is a warmwater stream.

| Chillisquaque Creek Chilisquaque Creek | |

|---|---|

Chillisquaque Creek looking downstream above Washingtonville | |

| Etymology | probably "place of the snow-birds", but possibly "flight of the wild goose", "frozen duck", or "man made perfect" |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | confluence of Middle Branch Chillisquaque Creek and East Branch Chillisquaque Creek in Derry Township, Montour County, Pennsylvania |

| • elevation | 520 ft (160 m) |

| Mouth | |

• location | West Branch Susquehanna River in West Chillisquaque Township, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania |

• coordinates | 40°55′59″N 76°51′37″W |

• elevation | 430 ft (130 m) |

| Length | 20.2 mi (32.5 km) |

| Basin size | 112 sq mi (290 km2) |

| Basin features | |

| Progression | West Branch Susquehanna River → Susquehanna River → Chesapeake Bay |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | East Branch Chillisquaque Creek, Mud Creek, Beaver Run |

| • right | Middle Branch Chillisquaque Creek, West Branch Chillisquaque Creek |

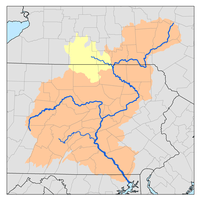

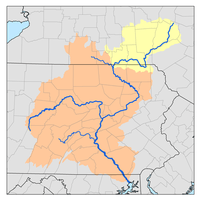

The watershed of Chillisquaque Creek occupies parts of four counties: Columbia County, Montour County, Northumberland County, and Lycoming County. There is a gauging station along the creek near Washingtonville. A Shawnee village had been established at the confluence with the West Branch Susquehanna River by 1728. A fort known as Fort Bosley also historically existed on the creek near Washingtonville. Numerous bridges were built over the creek in the 19th and 20th centuries, two of which are on the National Register of Historic Places. The creek is designated as a Warmwater Fishery and a Migratory Fishery. It lacks trout, but has in the past been stocked with various other fish species. A tract of the creek's floodplain is known as the Chillisquaque Creek Natural Area and is owned by Bucknell University. Various bird species have been observed near it and woodland wildflowers inhabit the creek's vicinity. Recreational opportunities in the watershed include canoeing and fishing.

Course

Chillisquaque Creek begins at the confluence of East Branch Chillisquaque Creek and Middle Branch Chillisquaque Creek near the northern border of Derry Township, Montour County. It flows west-southwest for a few tenths of a mile before turning south-southwest. After several tenths of a mile, it turns west for a short distance and receives the tributary West Branch Chillisquaque Creek from the right. The creek then turns south-southeast for more than a mile, flowing alongside Pennsylvania Route 54 and crossing it once. In this reach, it briefly flows alongside the western border of Washingtonville before crossing Pennsylvania Route 254 and receiving the tributary Mud Creek from the left. The creek then begins flowing in a roughly west-southwesterly direction and soon enters Liberty Township. It continues flowing in a similar direction in Liberty Township (though it does flow north, west, and then south for several tenths of a mile at one point), flowing through a broad valley with Limestone Ridge on the north and receiving many unnamed tributaries from both sides. After several miles, the creek leaves the valley and crosses Interstate 80. Several tenths of a mile further downstream, it exits Liberty Township and Montour County.[1]

Upon exiting Montour County, Chillisquaque Creek enters East Chillisquaque Township, Northumberland County. It then turns south-southeast for about a mile, flowing close to the county line and crossing Pennsylvania Route 642. In this reach, it receives Beaver Run, its last named tributary, from the left. The creek then turns southwest for a few tenths of a mile before turning south for a similar distance. It then turns west for several tenths of a mile before turning southwest. The creek crosses Pennsylvania Route 45 and meanders in a southwesterly direction for more than a mile, flowing along the border between East Chillisquaque Township and West Chillisquaque Township. It then turns south for a few tenths of a mile, passing the Rishel Covered Bridge as it continues flowing along the border. After this, the creek turns west-southwest, entering West Chillisquaque Township, before turning south and then west. For more than a mile, the creek flows through a valley between Montour Ridge and a smaller hill. Upon leaving the valley, the creek crosses Pennsylvania Route 147 and Pennsylvania Route 405 and heads in a southwesterly direction for several tenths of a mile before reaching its confluence with the West Branch Susquehanna River.[1]

Chillisquaque Creek joins the West Branch Susquehanna River 5.01 miles (8.06 km) upriver of its mouth.[2]

Tributaries

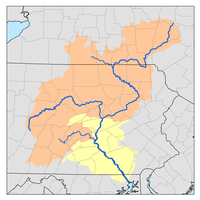

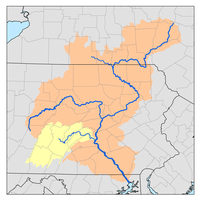

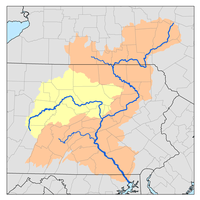

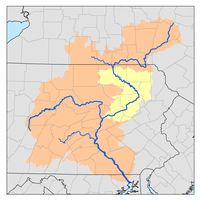

Chillisquaque Creek has five named direct tributaries: Beaver Run, Mud Creek, West Branch Chillisquaque Creek, East Branch Chillisquaque Creek, and Middle Branch Chillisquaque Creek.[1] Beaver Run joins Chillisquaque Creek 7.80 miles (12.55 km) upstream of its mouth and its watershed has an area of 12.0 square miles (31 km2). Mud Creek joins Chillisquaque Creek 16.79 miles (27.02 km) upstream of its mouth and its watershed has an area of 17.7 square miles (46 km2). West Branch Chillisquaque Creek joins Chillisquaque Creek 18.26 miles (29.39 km) upstream of its mouth. East Branch Chillisquaque Creek joins Chillisquaque Creek 19.96 miles (32.12 km) upstream of its mouth, as does Middle Branch Chillisquaque Creek. Their watersheds have areas of 9.75 square miles (25.3 km2) and 9.64 square miles (25.0 km2), respectively.[2]

Hydrology

Reaches of Chillisquaque Creek are designated as an impaired waterbody. Causes of impairment include sedimentation/siltation and habitat alteration, while likely sources include agriculture and industrial point-source discharge.[3] Many streams in the watershed experience significant impacts due to agriculture, as heavy use of agricultural lands reduces the creek's water quality. A total of 215 miles (346 km) of streams, or about 83% of all the stream miles in the watershed, are impaired.[4] The nearby Mahoning Creek is in "better environmental shape" than Chillisquaque Creek.[4] However, in the 1980s, the concentrations of pollutants in the creek were relatively low, despite being increased by discharges from a nearby power plant. For instance, the selenium concentration was consistently under 0.010 milligrams per liter, the United States Environmental Protection Agency criterion for that pollutant.[5]

Between 1980 and 2014, the highest average annual discharge of Chillisquaque Creek at Washingtonville was 146.0 cubic feet per second (4.13 m3/s), in 2011. The second-highest average annual discharge, 107.7 cubic feet per second (3.05 m3/s), occurred in 1984, while the third-highest, 104.4 cubic feet per second (2.96 m3/s), occurred in 2004. The lowest average annual discharge, 48.2 cubic feet per second (1.36 m3/s), occurred in 2001. The second-lowest, 52.2 cubic feet per second (1.48 m3/s), occurred in 1988 and the third-lowest, 52.4 cubic feet per second (1.48 m3/s), occurred in 2013.[6] The months with the highest average discharge are March, April, and December; their values are 125 cubic feet per second (3.5 m3/s), 104 cubic feet per second (2.9 m3/s), and 100 cubic feet per second (2.8 m3/s), respectively.[7] The PPL power plant contributes about 10 cubic feet per second (0.28 m3/s) of water to the creek.[8]

During several measurements in the 1970s, the pH of Chillisquaque Creek near Washingtonville ranged from 6.3 to 7.1. The specific conductance of the creek ranged from 170 to 250 micro-siemens per centimeter at 25 °C (77 °F). The turbidity ranged between 2 and 7 Jackson Turbidity Units. The concentration of water hardness in the creek ranged from 84 to 130 milligrams per liter. The concentration of dissolved oxygen ranged from 9.0 to 11.0 milligrams per liter, while the hydrogen ion concentration ranged from 0.00008 to 0.00051 milligrams per liter. The carbon dioxide concentration ranged between 4.7 and 49 milligrams per liter.[9]

In the 1970s, the concentration of nitrate as nitrogen in Chillisquaque Creek near Washingtonville ranged from 1.68 to 2.00 milligrams per liter, while the concentration of nitrite as nitrogen ranged from 0.040 to 0.164 milligrams per liter. The concentration of phosphorus ranged from 0.040 to 0.520 milligrams per liter. The organic carbon concentration was 3.0 milligrams per liter in one measurement. The concentration of sulfate ranged from 32.0 to 114 milligrams per liter in the creek's filtered water and the chloride concentration ranged between 8.0 and 14.0 milligrams per liter, again in filtered water. The ammonia concentration ranged from 0.026 to 0.811 milligrams per liter.[9]

In the 1970s, the concentration of magnesium in Chillisquaque Creek ranged from 1.50 to 9.50 milligrams per liter in the creek's filtered water and the calcium concentration ranged from 26.4 to 48.8 milligrams per liter, in filtered water. The arsenic concentration was once measured to be 77 micrograms per liter. The cadmium, recoverable chromium, and recoverable copper concentrations were each once measured to be less than 3, less than 20, and 30 micrograms per liter, respectively. The recoverable iron concentration ranged from 160 to 410 micrograms per liter. The concentrations of zinc, lead, manganese, and aluminum were less than 20, less than 50, 50, and 500 micrograms per liter, respectively. Additionally, a detectable amount of nickel was observed in the creek.[9]

Geography, geology, and climate

The elevation near the mouth of Chillisquaque Creek is 430 feet (130 m) above sea level.[10] The elevation of the creek's source is approximately 520 feet (160 m) above sea level.[1] The gradient of the creek is about 3 feet per mile (0.57 m/km).[8]

The upper reaches of the watershed of Chillisquaque Creek are in the Muncy Hills.[11] Montour Ridge is located to the south of the watershed.[12] Additionally, Limestone Ridge is situated near the creek.[13] The creek's drainage basin mainly consists of rolling agricultural land, with some forested floodplains.[8][12] Much of the central part of Montour County is in the 100-year floodplain of the creek and its tributaries.[14] In places, it has high, muddy banks, and is generally "placid", save for some riffles and gravel bars. It is rarely blocked by fences and fallen trees, but there are a few strainers.[8] A seep is located along the creek near the Bucknell preserve and a spring is located below Pennsylvania Route 54.[8][15]

Chillisquaque Creek cuts a broad and almost flat valley through rock of the Hamilton Group. It is 2 to 3 miles (3.2 to 4.8 km) wide and rarely rises to more than 50 feet (15 m) higher than the creek.[13] A 1775 map shows the creek's headwaters as being at Tilghmans Springs. However, A. Joseph Armstrong (author of Trout Unlimited's Guide to Pennsylvania Limestone Streams) was unable to find the springs. The creek is between 20 and 30 feet (6.1 and 9.1 m) wide and has no apparent limestone influence, despite being near Limestone Ridge and flowing through Limestone Township.[16]

Chillisquaque Creek flows in a generally southwesterly direction. The channel of the creek is sinuous and flows through rock formations consisting of sandstone and shale.[12] Oriskany sandstone and Lower Helderberg limestone occur on Limestone Ridge near it. Oriskany cherty sandstone occurs near the confluence of the tributary Mud Creek. Additionally, Black Genesee shales have also been observed near the creek, as does the Tully limestone. Rock of the Hamilton Group is common in the area as well and is in places covered with sandstone boulders of the Pocono Formation.[13] Hydric soils occur along it in central Montour County.[14]

In the early 1900s, the average annual rate of precipitation in the watershed of Chillisquaque Creek was 35 to 45 inches (89 to 114 cm).[12] The creek has relatively warm water.[16]

Watershed

The watershed of Chillisquaque Creek has an area of 112 square miles (290 km2).[2] The mouth of the creek is in the United States Geological Survey quadrangle of Northumberland. However, its source is in the quadrangle of Washingtonville. The creek also passes through the quadrangle of Milton.[10] The creek can be accessed from Pennsylvania Route 45, Pennsylvania Route 405, and Pennsylvania Route 642.[17]

The watershed of Chillisquaque Creek parts of four counties: Montour County, Northumberland County, Columbia County, and Lycoming County.[12] The portion of Montour County that is in the watershed is the central portion. It is the largest watershed in that county, accounting for 56 percent of its land area.[4] It is also the only large stream in northern Northumberland County.[13] There are about 260 miles (420 km) of streams in the watershed.[4]

The land alongside Chillisquaque Creek is mainly used for farming. As of the 1980s, the main crops are corn and soybeans.[5]

There is a gauging station on Chillisquaque Creek at Washingtonville. The area of the creek's watershed upstream of this point is 51.3 square miles (133 km2).[9] A reservoir known as Lake Chillisquaque is located on the tributary Middle Branch Chillisquaque Creek in Anthony Township, Montour County.[4] It is the largest lake/reservoir in Montour County, with an area of 165 acres (67 ha).[4][18] There are two dams in the watershed: the Lake Chillisquaque dam and the Montour Ash Basin No 1 dam. Both were built in 1971. The former drains an area of 5.6 square miles (15 km2), while the latter drains an area of 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2).[18]

History

Chillisquaque Creek was entered into the Geographic Names Information System on August 2, 1979. Its identifier in the Geographic Names Information System is 1171784. The creek is also known as Chilisquaque Creek.[10] Its name most likely comes from the Shawnee word chilisuagi, meaning "place of the snow-birds".[11] However, other possible meanings of the word include "flight of the wild goose", "frozen duck", and "man made perfect".[11]

The Shawnee Indians historically had a large village/town at the mouth of Chillisquaque Creek.[11][19] The village was established by 1728 and was known as Chenastry and Otzinachson.[19] The Shawnees on the creek moved to Western Pennsylvania in 1728.[20] Additionally, Andrew Montour historically owned a plantation near the creek's mouth.[19] In 1745, Bishop Spagenberg passed by the creek and noted the former Indian village there in his journal.[21] A Mingo chief named Logan was living at the mouth of the creek in about 1753.[22] An elderly couple were scalped by Indians near the creek in 1782.[19]

A frontier fort known as Fort Rice used to be located on Chillisquaque Creek near what is now Washingtonville.[23] William Plunket had settled near Chillisquaque Creek as early as 1772. Boyd and Wilson built a mill at the mouth of the creek in 1791. The first Methodist camp meeting in the area was held on the creek 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the West Branch Susquehanna River in August 1806.[22] The creek was declared a public highway in the 1820s.[24] The West Branch Division of the Pennsylvania Canal historically had an aqueduct over the creek. However, by 1842, it was in need of repairs.[25] In July 18 and 19, 1851, a 32-hour-long storm caused Chillisquaque Creek to rise higher than it had in 57 years.[22]

In the early 1900s, the main industries in the creek's watershed included agriculture and clay mines. The creek was also used as water power for a number of small mills. Around this time period, railroads in the watershed included the Susquehanna, Bloomsburg, and Berwick Railroad and the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. Major communities included Exchange, Jerseytown, Potts Grove, Washingtonville, Strawberry Ridge, and White Hall. Their populations were 225, 200, 184, 183, 160, and 140, respectively.[12]

Numerous bridges have been constructed over Chillisquaque Creek in Montour County. A bridge known as the Washingtonville Bridge was built in 1887 and is on the Historic American Buildings Survey.[26] Another one, which carries Pennsylvania Route 54, was built in 1930. Another bridge was built in 1946 and carries Pennsylvania Route 254 in Washingtonville. A bridge carrying State Route 4008 was built across the creek in 1957 and was repaired in 2010. A bridge carrying State Route 1004 was built across the creek in 1960. Additionally, two bridges carrying Interstate 80 were built over the creek in 1962 and repaired in the late 1990s. A bridge carrying State Route 4004 over the creek was built in 1987 and another bridge carrying Pennsylvania Route 54 was built in 1992. A bridge carrying State Route 1003 was constructed across the creek in 1993 and a bridge carrying State Route 3003 was built over the creek in 1997. In 2005, another bridge carrying State Route 1004 was built over the creek.[27]

A number of bridges have been built over Chillisquaque Creek in Northumberland County as well. One of these was the Rishel Covered Bridge, which was built in 1830 and repaired in 1990. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Gottlieb Brown Covered Bridge, which carries T594, was built across the creek in 1881 and was repaired in 1985. It is also on the National Register of Historic Places. A bridge carrying State Route 1025 was constructed over the creek in 1926 and a bridge carrying Pennsylvania Route 45 was built over the creek in 1952. A three-span bridge carrying Pennsylvania Route 642 was built over the creek in 1958 and was repaired in 2012. A two-span bridge carrying Pennsylvania Route 405 was built over the creek in 1974.[28]

A number of studies and inventories have been carried out on Chillisquaque Creek.[15] Such studies include Pennsylvania's 208 Study in 1979, an assessment by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and an assessment by Bucknell University in 2003.[4]

Biology

The drainage basin of Chillisquaque Creek is designated as a Warmwater Fishery and a Migratory Fishery.[29] The creek was observed by A. Joseph Armstrong to lack trout.[16] In 1986, the creek was not being stocked.[17] However, it was stocked with black bass, sunfish, and yellow perch in 1934 and with yellow perch in the spring of 1936.[30][31] In 1986, it contained many of the species found in the West Branch Susquehanna River, including rock bass.[17] Smallmouth bass have also been observed in the creek. Disease is moderately common among young-of-the-year smallmouth bass in the creek. 2011 was the first year where diseased smallmouth bass were documented in the creek since studies began in 2009.[32]

A tract of forested floodplain known as the Chillisquaque Creek Natural Area (or Bucknell Preserve, Tobias Marsh, or Mexico Road Swamp) is located in Liberty Township, Montour County.[15][33] A deciduous bottomland forest with pools and channels occurs along the creek, while more mesic forests occur higher up.[15] The tract of land is owned by Bucknell University, whose students and faculty sometimes conduct research there. The tract has an area of 66 acres (27 ha) and has a high level of tree biodiversity. Common tree species include basswood, bitternut hickory, pin oak, and shagbark hickory.[33] In the preserve, there is also a population of cat-tail sedges. Graminoid marshes occur along the creek near Mexico Road. Such marshes are mainly dominated by cattails, grasses, rushes, and sedges.[15]

Reaches of Chillisquaque Creek in Derry Township, Montour County would benefit from additional riparian buffering consisting of native trees to mitigate the effects of nonpoint source pollution.[15] Woodland wildflowers such as bluebells occur along the creek in April.[8] Virginia cowslips, mint, skunk cabbage, mountain honeysuckle, and scallions also are common along it towards the end of April.[34]

A number of bird species occur at the Bucknell Preserve along Chillisquaque Creek. These include marsh wrens and soras. Virginia rails were observed at the site in 1980 and 1984, though it is likely that they still remain there. Additionally, several mussel species that require high levels of water quality to survive have been observed in the creek.[15] In the Montour County reach of the watershed of Chillisquaque Creek, livestock is commonly allowed access to streams.[4]

Recreation

At least 17.9 miles (28.8 km) of Chillisquaque Creek, from Pennsylvania Route 54 at Washingtonville downstream to its mouth, are navigable by canoe. The difficulty rating of the creek is 1 and the scenery is described in Edward Gertler's book Keystone Canoeing as "good". The creek is suitable for beginners and is typically canoeable from March to May, with the exception of dry years. Not much water is required to canoe on it. However, there is no access to the creek's mouth.[8]

A greenway corridor for Chillisquaque Creek was proposed in the Montour County Comprehensive Plan.[14] Fishing and boating are permitted on Lake Chillisquaque, though only non-powered and electric boats are allowed.[4] The best fishing opportunities on the creek are in the springtime.[17] However, A. Joseph Armstrong's book Trout Unlimited's Guide to Pennsylvania Limestone Streams described the creek as "not an attractive stream.".[16]

A campsite known as Shangri-La on the Creek is situated on Chillisquaque Creek at the base of Montour Ridge. It has 52 creekside sites and another 115 sites that are forested to varying degrees. Recreational opportunities at the site include fishing and Frisbee golf.[35]

A reach of Chillisquaque Creek was once a third-priority candidate for a Pennsylvania Scenic Rivers designation.[36]

See also

- Turtle Creek (West Branch Susquehanna River), next tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River going downriver

- Limestone Run (Union County, Pennsylvania), next tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River going upriver

- List of rivers of Pennsylvania

References

- United States Geological Survey, The National Map Viewer, archived from the original on April 5, 2012, retrieved July 11, 2015

- Pennsylvania Gazetteer of Streams (PDF), November 2, 2001, retrieved July 11, 2015

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2006 Waterbody Report for Chillisquaque Creek, retrieved July 11, 2015

- Montour County Conservation District (December 2009), Montour County Implementation Plan For The Chesapeake Bay Tributary Strategy (PDF), pp. 4–5, 7, 9, archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2014, retrieved July 12, 2015

- Health Risks of Toxic Emissions from a Coal-fired Power Plant, January 1, 1987, pp. viii, 34, ISBN 9780833008671

- United States Geological Survey, USGS 01553700 Chillisquaque Creek at Washingtonville, PA, retrieved July 12, 2015

- United States Geological Survey, USGS 01553700 Chillisquaque Creek at Washingtonville, PA, retrieved July 12, 2015

- Edward Gerlter (1984), Keystone Canoeing, Seneca Press, p. 289

- United States Geological Survey, USGS 01553700 Chillisquaque Creek at Washingtonville, PA, retrieved July 11, 2015

- Geographic Names Information System, Feature Detail Report for: Chillisquaque Creek, retrieved July 11, 2015

- Walter M. Brasch (1982), Columbia County Place Names, p. 56

- Water Supply Commission of Pennsylvania (1921), Water Resources Inventory Report ..., Parts 1–5, p. 287

- Israel Charles White (1883), The Geology of the Susquehanna River Regíon in the Six Counties of Wyoming, Lackwanna, Luzerne, Columbia, Montour, and Northumberland, pp. 4, 29, 207, 309, 318–319

- Montour County Planning Commission (April 2009), Montour County Comprehensive Plan Goals, Objectives Recommendations & Strategies (PDF), pp. 14–15, 70, retrieved July 12, 2015

- Pennsylvania Science Office of The Nature Conservancy (2005), Montour County Natural Areas Inventory 2005 (PDF), pp. 17, 34, 56, retrieved July 12, 2015

- A. Joseph Armstrong (2000), Trout Unlimited's Guide to Pennsylvania Limestone Streams, p. 203, ISBN 9780811729444

- Ronald L. Hoffman (May 1986), "Northumberland County", Pennsylvania Angler and Boater, pp. 18–19, retrieved July 13, 2015

- Montour County Multi-jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan: Appendix C – Hazard Profile (PDF), March 2007, pp. 2–3, retrieved July 12, 2015

- C.H. Sipe (1931), The Indian wars of Pennsylvania, pp. 450–451, 678, 748, ISBN 9785871748480

- Jerry E. Clark (February 5, 2015), The Shawnee, University Press of Kentucky, p. 22, ISBN 9780813148939

- Charles Augustus Hanna (1911), The Wilderness Trail: Or, The Ventures and Adventures of the ..., Volume 1, p. 191

- John Blair Linn (1877), Annals of Buffalo Valley, Pennsylvania, 1755–1855, pp. 5, 31, 271, 354, 552

- John Franklin Meginness (1857), Otzinachson, p. 186

- Pennsylvania (1827), Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, p. 59

- Pennsylvania. General Assembly. Senate (1842), Journal, Part 3, p. 158

- Washingtonville Bridge, Pennsylvania Legislative Route 47036, spanning Chillisquaque Creek (Derry Township), Washingtonville, Montour County, PA, retrieved July 12, 2015

- Montour County, retrieved July 11, 2015

- Northumberland County, retrieved July 11, 2015

- "§ 93.9l. Drainage List L. Susquehanna River Basin in Pennsylvania West Branch Susquehanna River", Pennsylvania Code, retrieved July 11, 2015

- Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (December 1934), October stocking tops 2,600,000 (PDF), p. 16, retrieved July 13, 2015

- Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (September 1936), Fish distribution: April, May and June (PDF), pp. 18, 24, archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2015, retrieved July 13, 2015

- G. Smith (2011), Investigation into factors leading to disease-related mortality of young-of-year smallmouth bass Micropterus dolomieu in the Susquehanna River Basin: 2011 (PDF), Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, pp. 8, 19, retrieved July 13, 2015

- Bucknell University, Ecological Habitats, retrieved July 12, 2015

- William V. McNaull (2005), My Travels By Canoe, ISBN 9781477172971

- Robert W. Sehlinger (March 19, 2007), Frommer's Best RV and Tent Campgrounds in the U.S.A., John Wiley & Sons, p. 695, ISBN 9780470069295

- The State Water Plan: Subbasin 10 : Lower West Branch Susquehanna River, 1979, p. i

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chillisquaque Creek. |