Catawissa Creek

Catawissa Creek (colloquially known as The Cat[2]) is a 41.8-mile-long (67.3 km)[3] tributary of the Susquehanna River in east-central Pennsylvania in the United States.[4] Its watershed has an area of 153 square miles (400 km2).[5]

| Catawissa Creek | |

|---|---|

The creek near Brandonville, Pennsylvania | |

| |

| Etymology | Corruption of the Algonquin word Gattawisi, meaning "Growing fat"[1] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Southwestern Luzerne County, Pennsylvania |

| Mouth | |

• location | Susquehanna River |

| Length | 41.8 mi (67.3 km) |

| Basin size | 153 sq mi (400 km2) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Hunkydory Creek, Spies Run, Messers Run, Davis Run, Rattling Run, Dark Run, Little Catawissa Creek, Crooked Run, Cranberry Run, Klingermans Run, Stranger Hollow, Long Hollow, Mine Gap Run, Fisher Run, Furnace Run |

| • right | Cross Run, Tomhicken Creek, Beaver Run, Scotch Run |

The waters of Catawissa Creek are highly acidic, with a pH of 4.5,[6] due to runoff from an abandoned mine in the creek's watershed.[7] Catawissa Creek is smaller than the nearby Fishing Creek due to a lack of major tributaries.[8]

Catawissa Creek starts in Luzerne County, not far from Hazleton. It flows west and slightly south into Schuylkill County before flowing north into Columbia County and then west to the Susquehanna River, which it flows into at Catawissa. It parallels Catawissa Mountain for a significant portion of its course.

The surface rock in Catawissa Creek largely consists of sedimentary rock, such as sandstone and shale. However, there is also coal in the watershed. Major soils in the creek's watershed include the Leck Kill soil and the Albrights series. Most of the steeper hills in the watershed are situated near the headwaters of the creek.

Coal mining was once a major industry in the Catawissa Creek watershed, but this is no longer the case. Major tributaries of Catawissa Creek include Little Catawissa Creek and Tomhicken Creek. The president of the Catawissa Creek Watershed Restoration Association, Ed Wytovich, called Catawissa Creek "probably the most beautiful screwed-up stream east of the Mississippi".[2]

Hydrology

Audenried Tunnel

Where the Audenried Tunnel meets Catawissa Creek, the concentration of iron is 0.7 milligrams per liter (mg/L). The daily load of iron is 71.3 pounds (32.3 kg), which is 1.24 times the total maximum daily load allowed under the U.S. Clean Water Act. There are 2.28 mg/L of magnesium in the creek. The daily load of it is 232.4 lb (105.4 kg) per day, which is 3.73 times the total maximum daily load. Aluminium makes up 7.93 mg/L. The daily load is 808.2 lb (366.6 kg) per day, which is 19.8 times the total maximum daily load.[5] The total concentration of acidity in the creek is 68.08 mg/L. A total of 6,938.4 lb (3,147.2 kg) flow through the creek. This figure is 100 times the total maximum daily load.[5] The concentration of alkalinity is 2.31 mg/L, which equates to 235.4 lb (106.8 kg) per day.[5]

Green Mountain Tunnel

At the Green Mountain Tunnel, the concentration of iron is 0.44 mg/L, which equates to a load of 5.3 lb (2.4 kg) per day. There are 0.64 mg/L of manganese, which equates to a load of 7.7 lb (3.5 kg) per day. There are 2.97 mg/L of aluminium, meaning that 35.7 lb (16.2 kg) flow through each day. The amount of acidity is 28.06 mg/L, which equates to a load of 337 lb (153 kg) per day. Alkalinity takes up 3.29 mg/L, and 39.5 lb (17.9 kg) flow through per day.[5]

Catawissa Tunnel

Where the Catawissa Creek receives the Catawissa Tunnel, the concentration of iron is 1.01 mg/L, equating to a load of 6.9 lb (3.1 kg) per day. Manganese makes 0.31 mg/L, which is equivalent to a load of 2.1 lb (0.95 kg) per day. Aluminium's concentration is 1.27 mg/L, meaning that 8.7 lb (3.9 kg) flow through per day. The concentration of acidity is 18.44 mg/L, which equates to a load of 126.1 lb (57.2 kg) per day. Alkalinity comprises 4.11 mg/L, equating to a load of 28.1 lb (12.7 kg) per day.[5]

Catawissa Creek's headwaters

At Catawissa Creek's headwaters, the concentration of iron in the water is 0.34 mg/L. Manganese's level of occurrence is 1.74 mg/L. Aluminium's concentration is 3.2 mg/L. Acidity makes up 34.5 mg/L and alkalinity makes up 0.17 mg/L.[5]

At Susquehanna River

Where Catawissa Creek meets the Susquehanna River, the concentration of iron in the water is 0.11 mg/L, which equates to a load of 82.2 lb (37.3 kg) per day. Manganese's concentration is 0.33 mg/L, equating to a load of 246.6 lb (111.9 kg) per day. Aluminium's occurrence level is 0.85 mg/L, which equates to a daily load of 635.2 lb (288.1 kg). The concentration of acidity is 12.8 mg/L, meaning that 9,565 lb (4,339 kg) flow through per day. The concentration of alkalinity is 18.16 mg/L, which equates to a load of 13,570.3 lb (6,155.4 kg) per day.[5]

Below Messers Run

Shortly downstream of the confluence of Catawissa Creek with Messers Run, the pH of Catawissa Creek ranges between 4.1 and 6.2, with an average of 4.5. Further downstream, at Davis Run, the pH changes to 4.5 to 4.9, and averages 4.64. After picking up Rattling Run, Dark Run, and Little Catawissa Creek, but before picking up Tomhicken Creek, Catawissa Creek's pH ranges from 3.2[5] to 6.4 and averages 4.96. After the confluence with Tomhicken Creek, Catawissa Creek's pH ranges from 4.7 to 5.4.[5]

Despite the presence of acid mine drainage in Catawissa Creek, its waters are largely clear.[2]

Geology

From Catawissa Creek's source to Mainville, the creek's river valley is steep and narrow, and from Mainville to the creek's mouth, the river valley is more rolling.[5]

Interbedded sedimentary rock makes up 93% of the surface rock in the Catawissa Creek watershed, while the remaining 7% is sandstone.[5] South of Mainville, the Catawissa Creek river valley is made of red shale. There is also conglomerate, greenish-gray sandstone, olive-colored shale, and anthracite coal near Catawissa Creek.[9][10]

The geological features near the headwaters of Catawissa Creek primarily include anthracite and ridges of sandstone. The valleys in this part of the watershed are narrow and steep. Elsewhere in the watershed, the topography consists mostly of less steep valleys and some hills.[5]

McCauley Mountain and Green Mountain form the sides of the Catawissa Creek valley in Beaver Township, Columbia County. McCauley Mountain has a gradual slope near the creek.[11]

At the location where Catawissa Creek flows past Nescopeck Mountain in Main Township, there is a 580 feet (180 m) layer of rock known as the Pocono Formation. Below it, there is a 375 ft (114 m) layer of rock called the Pocono-Catskill Formation. Below the Pocono-Catskill Formation is a layer of red shale that is 100 ft (30 m) thick.[11]

A formation of greenish-gray sandstone near Catawissa Creek has been quarried for use in building. Below this layer is an olive colored sandstone that is home to Spirifer fossils. This layer is 40 ft (12 m) to 50 feet (15 m) thick. In a layer of red shale that is at least 100 ft (30 m) thick, there are fucoid fossils.[10]

Soils

A type of soil known as the Leck Kill soil occurs along Catawissa Creek. Usually, cultivated Leck Kill soils are topped with an 8-inch (200 mm) thick layer of dark brown silt loam, with a subsoil of reddish-brown silt loam that extends to a depth of 32 inches (810 mm). Below the subsoil is a 6-inch (150 mm) thick layer of clay loam. The bedrock below this type of soil is red shale.[12]

The Albrights series also occurs along Catawissa Creek. This type of soil is topped by a 7-inch (180 mm) thick layer of reddish-brown gravelly silt loam. Below this layer, there is a subsoil of yellowish-red silty clay loam. Below the subsoil is a layer of mixed gravel and silty clay loam. Bedrock occurs several feet underground.[12]

Course

Luzerne County

Catawissa Creek's source is in a strip mine area in southern Luzerne County and northern Schuylkill County near Audenried and McAdoo,[5][13] a few miles southwest of the city of Hazleton. However, it quickly becomes lost in the strip mines of the area. The creek resurfaces in an iron-filled pool west of Interstate 81.[5] It runs west through another strip mine before passing into Schuylkill County.[13]

Schuylkill County

Upon entering Schuylkill County in East Union Township, Catawissa Creek flows approximately west-southwest into a valley. In the valley, it goes past the geographical features called Round Head and Blue Head, picking up a tributary near Blue Head. Beyond Blue Head, the creek flows past Sheppton and then Brandonville. It picks up a tributary called Rattling Run at the edge of the township, shortly before entering Union Township.[14]

As the creek enters Union Township, its valley briefly becomes very deep before becoming shallower again. It picks up Dark Run in the township. The creek flows along the East Union Township/Union Township border before entering North Union Township.[15] Upon entering North Union Township, Catawissa Creek flows northwards until it reaches the community of Zion Grove, where it takes a sharp turn northwest. At Zion Grove, the walls of the creek's valley again become considerably higher and steeper. As it exits Zion Grove, it picks up Tomhicken Creek. Catawissa Creek takes a sharp turn to the west and flows under Red Ridge. At the western edge of Red Ridge, the creek takes a sharp turn northwards, followed shortly afterwards by a gentle turn westwards. It picks up Crooked Run at the edge of North Union Township, and then flows into Columbia County.[16]

Columbia County

Catawissa Creek enters Columbia County in Beaver Township. It immediately passes by Bunker Hill and makes several meanders and passes by Beaver Valley. An old Conrail railroad starts paralleling Catawissa Creek at this point. In the southern part of Beaver Township, the creek is situated between Buck Mountain to the east and Catawissa Mountain to the west. The creek takes a sharp turn westwards as it passes by Shumans, where Pennsylvania Route 339 crosses the creek and Beaver Run flows into it. The creek closely follows Catawissa Mountain for a short distance before turning northwards and passing close to McCauley Mountain. It meanders past Dry Ridge and then Full Mill Hill, where Pennsylvania Route 339 crosses it again. The creek makes a hairpin turn northwards and picks up Gap Run before exiting Beaver Township.[17]

Leaving Beaver Township, the creek enters Main Township. It continues following Catawissa Mountain, and, for a shorter distance, Full Mill Hill. It picks up Gap Run and Fisher Run from the left, Scotch Run from the right,[17] and Furnace Run from the left in quick succession. After picking up Furnace Run, Catawissa Creek flows between Catawissa Mountain and Nescopeck Mountain in a high, narrow gorge. As the creek leaves the gorge, it passes Mainville and enters a plain. The creek turns west-southwest and the plain narrows slightly. On the south side of the plain is Catawissa Mountain and on the north side are lower hills. After a few miles, the creek flows out of Main Township and into Catawissa Township.[18] In Catawissa Township, the creek flows southwest to Catawissa. It follows the southern border of Catawissa until it reaches its edge and turns northwards, following the western border of Catawissa. Pennsylvania Route 487 crosses over the creek at this point. At the western edge of Catawissa, the creek empties into the Susquehanna River.[19]

History

Early history

Catawissa, meaning "growing fat", was the name applied to the stream by the Native American tribes which originally occupied the area at the mouth of Catawissa Creek. Fur traders lived along the Catawissa as early as 1728.[20] According to legend, Catawissa Creek got its name because an Indian killed a deer near there "in the season when the animal fattens".[1]

Modern history

Settlers of European descent arrived on or near Catawissa Creek before 1776. The settlers included Alexander McCauley and Andrew Harger. McCauley left the area in 1776 and Harger was abducted by Indians. The Englishman Thomas Wilson was another early settler in the area. He lived in a cave on Catawissa Creek. The first mill in Columbia County was built on Catawissa Creek in 1774.[11] Two other mills were built on the Creek in 1789 and 1799.[21]

In 1826, a forge was built on Catawissa Creek for making bar iron.[9] By the late 1820s, there were plans to build a railroad paralleling Catawissa Creek and connecting Catawissa with Pottsville.[22] The Catawissa Railroad, which was built in the 1830s, paralleled Catawissa Creek for part of its course. Another railroad that historically paralleled Catawissa Creek was the Danville, Hazleton and Wilkes-Barre Railroad, which was built in 1870.[11] A paper mill was established on Catawissa Creek in Catawissa in 1811.[23] In the late 19th century a dam was built on Catawissa Creek in Beaver Township.[9]

In 1886, a bridge known as the Catawissa Creek Bridge was built over Catawissa Creek by Columbia County. It was located at what was then Reichard's switch on the Philadelphia and Reading Railway. The bridge was destroyed by a flood in 1902, but later rebuilt. It was again carried away about 200 feet (61 m) downstream by ice and flooding on March 7, 1904, although it remained intact despite being carried away. The bridge, however, was not rebuilt again in that location.[24]

From the middle of the 19th century until the early part of the 1970s, coal was mined in the eastern portion of the Catawissa Creek watershed.[5] The coal was primarily mined in the Jeansville Coal Basin and the Green Mountain Coal Basin.[5] The Catawissa Water Company once used water from Catawissa Creek.[25] Five drainage tunnels were built in the watershed in the 1930s, and they still discharge acid mine drainage in the 21st century. Strip mining has occurred in parts of the watershed, mainly the Catawissa Creek headwaters and the Little Tomhicken Creek sub-watershed.[5]

While deep mining of coal in the Catawissa Creek watershed ceased in the 1970s, strip mining still continued for some time. However, in the 21st century, there are still five mining permits in the watershed and some coal is still extracted from refuse banks.

Several surveys of Catawissa Creek have been performed by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. The first one was in 1957. There were two more surveys of chemical hydrology in 1966 and 1976. In 1997, the commission assessed the creek and its tributaries for usability as fisheries for the first time.[5]

There have been several attempts in the late 20th century and 21st century to raise the pH of Catawissa Creek. Between 1998 and 2000, the Catawissa Creek Restoration Association added limestone sand into the creek, but were not successful in raising the pH. However, in 2001, the Oneida #1 treatment system successfully neutralized the tributary Sugarloaf Creek.[5] As of 2000, there have been plans to reroute Catawissa Creek away from the Audenried Tunnel and the Green Mountain Tunnel.[26] The Catawissa Creek Watershed Restoration Association was established in 1997.[27]

Catawissa Creek is the subject of at least two 1862 paintings by Thomas Moran: On the Catawissa Creek, now on display in the University Of Virginia Art Museum and Valley of the Catawissa in Autumn at the Crystal Bridges Art Museum[28][29]

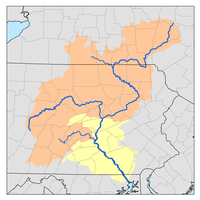

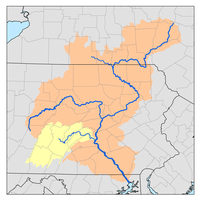

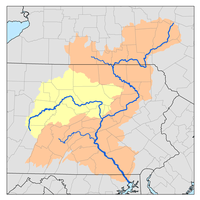

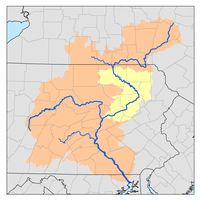

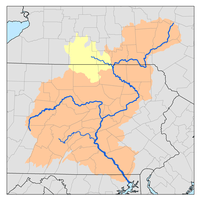

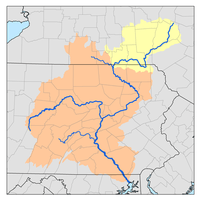

Watershed

Catawissa Creek's watershed ranges through four counties: Columbia County, Schuylkill County, Luzerne County, and Carbon County. The area of the watershed in Columbia and Schuylkill Counties are both large, with the area in Luzerne County being considerably smaller. The area in Carbon County consists of only a few square miles Tresckow.[30]

Pennsylvania Route 339 and Pennsylvania Route 924 are the main highways in the Catawissa Creek watershed. They both run along the creek for some distance. However, Interstate 81 passes by the creek's headwaters and there are many township roads throughout the watershed. The communities of McAdoo and Kelayres are on the extreme eastern edge of the watershed. Sheppton and Oneida are also in the watershed.[31]

The Hollingshead Covered Bridge No. 40 crosses Catawissa Creek.[32]

There are five drainage tunnels in the Catawissa Creek watershed: the Audenried, Oneida #1, Oneida #3, Catawissa, and Green Mountain. Audenried Tunnel drains the Jeansville Coal Basin on the eastern edge of the watershed. Oneida #1 empties into, Sugarloaf Creek, a tributary of Catawissa Creek. The Oneida #3 empties into Tomhicken Creek, another tributary of Catawissa Creek. The other two empty into Catawissa Creek itself, relatively close to each other. The Audenried Tunnel is responsible for 80% of the acid mine drainage flowing into Catawissa Creek.[5]

Out of the land in the Catawissa Creek watershed, 78.4% is forested, 17.4% is agricultural, and 1% is developed. Two percent of the land in the watershed is former coal-mining land, such as old coal mines and quarries.[5]

Fauna and flora

Some of Catawissa Creek's tributaries are known to contain trout, but the creek itself does not contain any fish due to pollution from acidic mine drainage.[5][33] In 1966, some woodcocks were observed to live along Catawissa Creek.[12]

Rhododendrons and hemlocks typically grow close to Catawissa Creek, while hardwood trees grow higher up in Catawissa Creek's river valley.[34] In the late 1800s, a large number of plants resembling fucoids were discovered along Catawissa Creek near the border of Main and Catawissa Townships.[35]

In the late 1950s, Catawissa Creek was found by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission to have good temperatures for trout habitation, but there was no aquatic life in the creek due to acid mine drainage. This situation continued through the 1960s and 1970s. However, by 1997, large populations of wild trout were found on some tributaries of Catawissa Creek. As of 2003, Catawissa Creek is considered to be a cold-water fishery between its headwaters and its confluence with Rattling Run. Several other tributaries, namely Dark Run, Davis Run, Little Catawissa Creek, and Messers Run are designated as high-quality cold water fisheries.[5]

Aquatic macroinvertebrates are not common in and around Catawissa Creek, as of 2003. However, some adult members of the Allocapnia and Taeniopteryx genera have been observed. Large numbers of Amphinmeura and Leuctra have also been observed on the creek between its headwaters and the Audenried and Green Mountain tunnels.[36]

Tributaries

Spies Run and Davis Run are two tributaries that flow into Catawissa Creek within a few miles of its headwaters. Spies Run is about one mile long and joins Catawissa Creek from the south.[37] Davis Run is slightly longer, about 1.5 miles (2.4 km). It also joins Catawissa Creek from the south, near Brandonville.[38] Rattling Run, a 2.3 miles (3.7 km) tributary, also flows into Catawissa Creek from the south near Brandonville.[38]

The next tributaries of Catawissa Creek going downstream are Dark Run and Little Catawissa Creek. Dark Run is close to four miles long and flows into Catawissa Creek from the southwest. Little Catawissa Creek is approximately ten miles long and flows into Catawissa Creek from the west, less than a mile downstream from Dark Run. Little Catawissa Creek starts near Centralia and passes by Ringtown.[39]

Tomhicken Creek is the next tributary of Catawissa Creek flowing downstream. It has a few tributaries, including Raccoon Creek and Sugarloaf Creek.[40] Approximately two miles downstream of Tomhicken Creek, Crooked Run, Cranberry Run and Klingerman's Run join Catawissa Creek from the south about 2 to 3 miles apart.[41]

In addition to Klingerman's Run, Fisher Run and Furnace Run flow down Catawissa Mountain to Catawissa Creek. Scotch Run flows into the creek from the east.[42]

Recreation

It is possible to paddle on much of Catawissa Creek for parts of the year. However, it is not usually possible to paddle on the creek during the summer. Upstream of Mainville, there are some riffles and small rapids. There is a larger rapid downstream of a lowdam in the lower reaches of the creek.[34]

See also

- Roaring Creek (Pennsylvania), next tributary of the Susquehanna River going downriver

- Corn Run, next tributary of the Susquehanna River going upriver

- List of rivers of Pennsylvania

References

- Thomas K. Donnalley, Larry S. Watson (editors) (1986), Handbook of Tribal Names of Pennsylvania: Together with Signification of Indian Words, p. 27, ISBN 9780942594119CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Ad Crable (July 26, 2006). "No longer dead in the water". Lancaster Online. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-04-05 at WebCite, accessed August 8, 2011

- Gertler, Edward. Keystone Canoeing, Seneca Press, 2004. ISBN 0-9749692-0-6

- CATAWISSA CREEK WATERSHED TMDL: Carbon, Columbia, Luzerne, and Schuylkill Counties (PDF), EPA, March 1, 2003, retrieved October 31, 2013

- Franklin L. Curry (2011). Clean Politics, Clean Streams: A Legislative Autobiography and Reflections. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 171. ISBN 9781611460735.

- Remediating the Audenreid Mine Tunnel Discharge (PDF), Susquehanna River Basin Commission, January 2005, archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013, retrieved October 24, 2013

- John H. Brubaker (2002), Down the Susquehanna to the Chesapeake, Penn State Press, p. 73, ISBN 0271046651

- Charles B. Trego (July 31, 1863), A Geography of Pennsylvania: Containing an Account of the History, pp. 52, 222

- Geological Survey of Pennsylvania (1889), Report of Progress, Board of Commissioners for the Second Geological Survey, pp. 255, 279–280

- J.H. Beers (1915), Historical and Biographical Annals of Columbia and Montour Counties

- United States. Bureau of Soils; et al. (1967), Soil survey, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, pp. 26, 69

- USGS, Luzerne County, archived from the original on October 31, 2013, retrieved October 28, 2013

- USGS, East Union Township, archived from the original on October 31, 2013, retrieved October 28, 2013

- USGS, Union Township, archived from the original on October 31, 2013, retrieved October 28, 2013

- USGS, North Union Township, archived from the original on November 2, 2013, retrieved October 29, 2013

- USGS, Beaver Township, archived from the original on November 2, 2013, retrieved October 29, 2013

- USGS, Main Township, archived from the original on November 2, 2013, retrieved October 29, 2013

- USGS, Catawissa Township, archived from the original on November 2, 2013, retrieved October 29, 2013

- Edwin B. Barton (1976). Columbia County two hundred years ago. Columbia County Historical Society. p. 13. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- J.H. Battle (1887), CATAWISSA TOWNSHIP, retrieved October 24, 2013

- Samuel Hazard (editor) (1828), Hazard's Register of Pennsylvania, p. 427CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Columbia County Historical and Genealogical Society (2009), Early Columbia County, p. 115, ISBN 9780738572017

- Pennsylvania county court reports, 1905, p. 261

- J. H. Battle (editor) (1887), History of Columbia and Montour Counties, PennsylvaniaCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gerry Ulicny (February 7, 2000), Schuylkill Groups Seek Waterway Grants * Largest Project Would Be Catawissa Creek Restoration To End Acid Mine Pollution., The Morning Call, retrieved November 9, 2013

- Stephen J. Pytak (January 18, 2012), County gives out watershed grants, Republican Herald, retrieved November 14, 2013

- Two New Gifts On Display At The University Of Virginia Art Museum, November 12, 2002, archived from the original on 2015-01-18, retrieved November 14, 2013

- Hutter, Hillary. "EXPLORING FALL COLORS AT CRYSTAL BRIDGES". Crystal Bridges Blog. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Michael A. Hewitt, CattyBaseMap, retrieved October 30, 2013

- EPA (March 1, 2003), CATAWISSA CREEK WATERSHED TMDL (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013, retrieved October 24, 2013

- "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Bill Pennesi and Susan M. Zacher (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Hollingshead Covered Bridge No. 40" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- Genetic Studies of Fish, Ardent Media, 1974, p. 14, ISBN 9780842271776

- Jeff Mitchell (2009), Paddling Pennsylvania: Canoeing and Kayaking the Keystone State's Rivers and Lakes, Stackpole Books, pp. 90–91, ISBN 9780811736268

- White, Israel Charles (1887), The geology of the Susquehanna River region in the six counties, p. 60

- Catawissa Creek Watershed Restoration Plan Update Addressing the TMDL (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on November 9, 2013, retrieved November 9, 2013

- Google Maps, 2013, retrieved November 6, 2013

- Google Maps, 2013, retrieved November 6, 2013

- Google Maps, 2013, retrieved November 6, 2013

- Google Maps, 2013, retrieved November 6, 2013

- Google Maps, 2013, retrieved November 9, 2013

- Google Maps, 2013, retrieved November 9, 2013

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catawissa Creek. |