Chevening

Chevening House is a large country house in the parish of Chevening in Kent, in south east England. Built between 1617 and 1630 to a design reputedly by Inigo Jones and greatly extended after 1717, it is a Grade I listed building.[1] The surrounding gardens, pleasure grounds and park are listed Grade II*.[2]

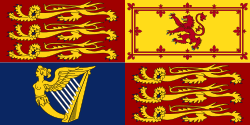

Formerly the principal seat of the Earls Stanhope, the house and estate are owned and maintained at the expense of the trust of the Chevening Estate, under the Chevening Estate Act 1959[3] (amended 1987), to serve as a furnished country residence for a person nominated by the Prime Minister, so qualified by being a member of the Cabinet or a descendant of King George VI. The nominee pays for their own private living expenses when in residence but government departments arrange and effect official business at the estate.[4] Chevening House is not an official residence.

History

There has been a house on the site since at least 1199 and the estate originally formed part of the archiepiscopal manor of Otford. The present 15-bedroomed house is a three-storey, symmetrical red brick structure in the early English Palladian style, attributed to Inigo Jones, set at the foot of the North Downs in extensive parkland. A garden to the south encircles a man-made lake. The house was extended from 1717 by the addition of symmetrical wings by Thomas Fort, a master carpenter and royal clerk of works who had worked under Wren at Hampton Court. Much remodelled by the 3rd Earl Stanhope in the late 18th century, the house was extensively restored in the 1970s by Donald Insall Associates for the Board of Trustees of the Chevening Estate.

The house was for 250 years the principal seat of the Earls Stanhope, a cadet (and ultimately the final) branch of the Earls of Chesterfield, from 1717 to 1967. James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope, was a general under Marlborough and a Whig politician who served as chief minister to King George I until his death in 1721. Through marriage he was the uncle of William Pitt the Elder. Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl Stanhope, was tutored by the 4th Earl of Chesterfield and became a distinguished patron of science during the Enlightenment. Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope, both first cousin and brother-in-law to William Pitt the Younger, was a prolific inventor whose major achievements in such diverse fields as printing, building a mechanical calculator, steam navigation, optics, musical notation and fire-proofing in buildings were overshadowed at the time and subsequently by his reputation, as the self-styled "Citizen Stanhope", for eccentricity and political radicalism. Philip Henry Stanhope, 4th Earl Stanhope, was a gifted amateur landscape gardener and architect, half-brother to Lady Hester Stanhope, and the legal guardian of Kaspar Hauser. Philip Stanhope, 5th Earl Stanhope, was the driving force behind the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery and the Historical Documents Commission: writing as Viscount Mahon he was a distinguished 19th-century historian and established the Stanhope Essay Prize at Oxford. Arthur Stanhope, 6th Earl Stanhope, was a Conservative MP before inheriting and served as First Ecclesiastical Estates Commissioner from 1878 to 1903. Both his brothers made their careers in politics. The Rt Hon Edward Stanhope (Conservative) was a reforming Secretary of State for War (1887–1892), while the 1st Lord Weardale (Liberal) was president of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (1912–22) and of the Save the Children Fund. James Stanhope, 7th Earl Stanhope (also 13th Earl of Chesterfield), was a Conservative politician who held office almost continuously from 1924 to 1940, serving in Cabinet posts from 1936 under Baldwin and Chamberlain. He founded the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

Having no children of his own and his only brother having been killed in the Great War, the last Earl Stanhope wished to create at Chevening a lasting monument to a family that had provided for two and a half centuries politicians across the political spectrum and no less than five Fellows of the Royal Society. He therefore drafted what became the Chevening Estate Act 1959[5] to ensure that the estate would not be broken up after his death, but would instead retain a significant role as a private house in public life. The ownership of the property would pass to a Board of Trustees, who would maintain it as a furnished country residence for a suitably qualified Nominated Person chosen by the Prime Minister. The Nominated Person would have the right to occupy the house in a private capacity and would pay for their private living expenses. The Board of Trustees would maintain the house and estate by means of their stewardship of the estate, with no grant from the Government. The Act was passed with cross-party support and, as amended by the Chevening Estate Act 1987, governs the estate to this day. The first beneficiary of the Act was the 7th Earl, who died in 1967, following which the Board of Trustees launched a major programme of restoration of the house, gardens and parklands funded partly by his endowment and partly through their own management of the estate.[6]

In 1974 Charles, Prince of Wales, accepted the prospect of living on the estate. According to his biographer, Jonathan Dimbleby (for whom Prince Charles arranged access to unpublished royal diaries and family correspondence), at that time he was contemplating an eventual marriage to Hon. Amanda Knatchbull, granddaughter of his great-uncle the 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma: "[I]n 1974, following his correspondence with Mountbatten on the subject, the Prince had tentatively raised the question of marriage to Amanda with her mother (and his godmother), Lady Brabourne. She was sympathetic, but counselled delaying mention of the matter to her daughter, who had yet to celebrate her seventeenth birthday."[7] Amanda's paternal great-aunt had been Lady Eileen Browne, daughter of the 6th Marquess of Sligo, whose childless marriage to the last Earl Stanhope led to Chevening's being designated by law as a potential home for a member of Britain's Royal Family. If Amanda were to become Princess of Wales by marriage, the Prince's acceptance of Chevening would make some familial sense. But this was not to be, although the Prince did visit the house several times. In a note of 24 April 1978 to his private secretary, Sir David Checketts, Prince Charles observed, "I know there are advantages — particularly financial ones — in the Chevening set up, but I regret to say I am rapidly coming to the conclusion that they are the only advantages."[8] In June 1980 Prince Charles wrote to Prime Minister Thatcher to renounce residency at Chevening (without actually having resided there). Weeks later, he purchased Highgrove in Gloucestershire. By then, according to Dimbleby, Amanda Knatchbull, several of whose close family members had been recently murdered, had declined the Prince's proposal of marriage,[9] and he would soon begin courtship of Lady Diana Spencer.[10]

Current use

Under the terms of the Chevening Act the Prime Minister has the responsibility of nominating a person to occupy the house privately as a furnished country residence. This person can be the Prime Minister, a minister who is a member of the Cabinet, a lineal descendant of King George VI or the spouse, widow or widower of such a descendant. The Canadian High Commissioner, the American Ambassador and the National Trust all have remainder interests in Chevening in the unlikely event that none of the others requires the house.

The usual nominee is the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs. Under special arrangements with the Board of Trustees the house is also available to the Secretary of State for International Trade and the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union. When circumstances permit, the house may be used for meetings or conferences, usually by other Government departments, through arrangement with the Trustees.

Alleged literary connection

It has sometimes been suggested that Chevening served Jane Austen as a model for Rosings Park in her novel Pride and Prejudice, but the only established fact that links the novelist with Chevening is that the Revd John Austen, her second cousin and grandson of the solicitor Francis Austen, who lived in the Red House, Sevenoaks, became Rector of Chevening in 1813, the novel having been published in that January.[11] However, it was written from October 1796 to August 1797. John Halperin also relates that Francis Austen, an uncle of Jane Austen's father, was solicitor to the owners of Chevening during the latter third of the 18th century; that Francis Austen owned property in the area, and that Jane Austen visited him and relatives in Kent several times between 1792 and 1796.[11]

Chevening scholarship programme

Chevening is the name of the UK government's international awards scheme, founded in 1983 to develop global leaders. While the programme takes its name from the house, the Chevening Secretariat administers the awards on behalf of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Secretariat is based at Woburn House in London and is part of the Association of Commonwealth Universities.

See also

- Chequers, the British Prime Minister's official country retreat, near Wendover in Buckinghamshire.

- Dorneywood, a country retreat in Burnham, Buckinghamshire, periodically assigned to a senior British government minister.

References

_after_Thomas_Badeslade_(d.1742)%2C_published_(in_History_of_Kent)_1719_by_John_Harris.jpg)

- Historic England. "Chevening House (1085853)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Historic England. "Chevening House (1000258)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Chevening Estate Act 1959 (1959 Chapter 49 7 and 8 Eliz 2)

- Newman, Aubrey (1969). The Stanhopes of Chevening. Macmillan.

- http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Eliz2/7-8/49/contents

- Wilson, Michael (2011). A House of Distinction.

- Dimbleby, J: page 263.

- Dimbleby, J: page 299.

- Dimbleby, J: page 265

- Dimbleby, J: page 279.

- Halperin, John (1989), "Inside Pride and Prejudice", Persuasions, Jane Austen Society of North America (11), retrieved 9 December 2018

Bibliography

- Newman, Aubrey. The Stanhopes of Chevening. Macmillan.

- Wilson, Michael. A House of Distinction.

- Dimbleby, Jonathan (1994). The Prince of Wales: A Biography. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0688129965.

- Sedgemore, Brian (1995). The Insider's Guide to Parliament. Cambridge: Icon Books. ISBN 1-874166-32-3.

.svg.png)