Eltham Palace

Eltham Palace is a large house at Eltham (/ˈɛltəm/) in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The house consists of the medieval great hall of a former royal residence, to which an Art Deco extension was added in the 1930s. The hammerbeam roof of the great hall is the third-largest of its type in England, and the Art Deco interior of the house has been described as a "masterpiece of modern design".[1] The house is owned by the Crown Estate and managed by English Heritage, which took over responsibility for the great hall in 1984 and the rest of the site in 1995.[2]

| Eltham Palace | |

|---|---|

| |

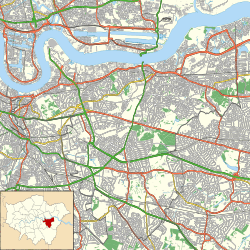

Eltham Palace Location within Royal Borough of Greenwich | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Art Deco interior |

| Location | Eltham London, SE9 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°26′50″N 00°02′53″E |

| Current tenants | English Heritage |

| Owner | Crown Estate |

| Website | |

| www | |

History

1300–1930

The original palace was given to Edward II in 1305 by the Bishop of Durham, Anthony Bek, and used as a royal residence from the 14th to the 16th century. According to one account, the incident which inspired Edward III's foundation of the Order of the Garter took place here. As the favourite palace of Henry IV, it played host to Manuel II Palaiologos, the only Byzantine emperor ever to visit England, from December 1400 to January 1401, with a joust being given in his honour. There is still a jousting tilt yard. Edward IV built the Great Hall in the 1470s, and a young Henry VIII when he was known as Prince Henry also grew up here; it was here in 1499 that he met and impressed the scholar Erasmus, introduced to him by Thomas More. Erasmus described the occasion:[3]

I had been carried off by Thomas More, who had come to pay me a visit on an estate of Mountjoy’s (the house of Lord Mountjoy near Greenwich) where I was staying, to take a walk by way of diversion as far as the nearest town (Eltham). For there all the royal children were being educated, Arthur alone excepted, the eldest son. When we came to the hall, all the retinue was assembled; not only that of the palace, but Mountjoy’s as well. In the midst stood Henry, aged nine, already with certain royal demeanour; I mean a dignity of mind combined with a remarkable courtesy…. More with his companion Arnold saluted Henry (the present King of England) and presented to him something in writing. I, who was expecting nothing of the sort, had nothing to offer; but I promised that somehow, at some other time, I would show my duty towards him. At the time I was slightly indignant with More for having given me no warning, especially because the boy, during dinner, sent me a note inviting something from my pen. I went home, and though the Muses, from whom I had lived apart so long, were unwilling, I finished a poem in three days.

Tudor courts often used the palace for their Christmas celebrations. With the grand rebuilding of Greenwich Palace, which was more easily reached by river,[4] Eltham was less frequented, save for the hunting in its enclosed parks, easily reached from Greenwich, "as well enjoyed, the Court lying at Greenwiche, as if it were at this house it self". The deer remained plentiful in the Great Park, of 596 acres (2.4 km2), the Little, or Middle Park, of 333 acres (1.3 km2), and the Home Park, or Lee Park, of 336 acres (1.4 km2).[5] In the 1630s, by which time the palace was no longer used by the royal family, Sir Anthony van Dyck was given the use of a suite of rooms as a country retreat. During the English Civil War, the parks were denuded of trees and deer. John Evelyn saw it 22 April 1656: "Went to see his Majesty's house at Eltham; both the palace and chapel in miserable ruins, the noble wood and park destroyed by Rich the rebel". The palace never recovered. Eltham was bestowed by Charles II on John Shaw and in its ruinous condition— reduced to Edward IV's Great Hall, the former buttery, called "Court House", a bridge across the moat and some walling—remained with Shaw's descendants as late as 1893.[5]

The current house was built in the 1930s on the site of the original, and incorporates its Great Hall, which boasts the third-largest hammerbeam roof in England.[6] Fragments of the walls of other buildings remain visible around the gardens, and the 15th-century bridge still crosses the moat.

The south side of the palace, with the medieval great hall on the left

The south side of the palace, with the medieval great hall on the left JMW Turner's painting of the great hall c.1793

JMW Turner's painting of the great hall c.1793.jpg) The great hall in 2018

The great hall in 2018

1930–present

In 1933, Stephen Courtauld and his wife Virginia "Ginie" Courtauld (née Peirano) acquired a 99-year lease on the palace site and commissioned Seely & Paget to restore the hall and create a modern home attached to it. Seely and Paget added a minstrel's gallery and a timber screen to the hall, while creating a design for the main house inspired by Christopher Wren's work at Hampton Court Palace and Trinity College Cambridge.[7]

The home was decorated internally in the Art Deco style. The dramatic Entrance Hall was created by the Swedish designer Rolf Engströmer. Light floods in from a spectacular glazed dome, highlighting blackbean veneer and figurative marquetry.[8] Other rooms in the house, including the dining room, drawing room and Virginia Courtauld's circular bedroom and adjoining bathroom, were the work of the Italian designer Piero Malacrida de Saint-August, while Seely and Paget designed many of the bedrooms.[7] Keen gardeners, the Courtaulds also substantially modified and improved the grounds and gardens.[9]

The Art Deco entrance hall

The Art Deco entrance hall Virginia Courtauld's bedroom

Virginia Courtauld's bedroom The library

The library The dining room

The dining room The drawing room

The drawing room

Stephen was a younger brother of Samuel Courtauld, an industrialist, art collector and founder of the Courtauld Institute of Art. His study in the new house features a statuette version of The Sentry, copied from a Manchester war memorial, by Charles Sargeant Jagger, who was - like Stephen - a member of the Artists' Rifles during the First World War.

The Courtaulds' pet lemur, Mah-Jongg, had a special room on the upper floor of the house which had a hatch to the downstairs flower room; he had the run of the house. The Courtaulds remained at Eltham until 1944. During the earlier part of the war, Stephen Courtauld was a member of the local Civil Defence Service. In September 1940 he was on duty on the Great Hall roof as a fire watcher when it was badly damaged by German incendiary bombs. In 1944, the Courtauld family moved to Scotland then to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), giving the palace to the Royal Army Educational Corps in March 1945; the Corps remained there until 1992.

In 1995, English Heritage assumed management of the palace, and in 1999, completed major repairs and restorations of the interiors and gardens.[9]

The palace and its garden are open to the public and can be hired for weddings and other functions. Most of the rooms have been restored to resemble their appearance during the Courtaulds' occupation (although it is uncertain how some of them were furnished) but some have been left as they were when the palace was used by the Educational Corps.

Public transport is available at the nearby Mottingham railway station or Eltham railway station, both a short walk from the palace.

Moat

Moat Garden

Garden- South Bridge

Filming

Many films and television programmes have been filmed at Eltham Palace, including:

- Bright Young Things

- I Capture the Castle

- High Heels and Low Lifes

- The Gathering Storm

- Home Front

- Any Questions

- The History of Romance

- This Morning

- Antiques Roadshow

- The Truth

- The 200 Year House

- The Crown

- Brideshead Revisited

- Hustle

- Secret Diary of a Call Girl

- Gucci by Gucci perfume commercial featuring James Franco

- Parachute, 2010 music video by Cheryl Cole

- Fry and Laurie: Reunited

- Revolver

- Shake It Out, 2011 music video by Florence and the Machine

- "Death on the Nile", 2004 episode of Poirot TV series.

- "Froot", 2014 music video by Marina and the Diamonds

- "Alone", 2017 music video by Jessie Ware

Haunting

Eltham Palace is listed on English Heritage's list of "most haunted places." The ghost of a former staff member is said to have given tours of the palace when the palace should have been empty.[10]

References

- "Eltham Palace". LondonTown.com. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "History of Eltham Palace and Gardens Access". English Heritage. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Collected Works of Erasmus, Toronto University Press, volume 9, letter 1341A. The reference can be found also in R. W. Chambers, Thomas More, 1935, edn 1976, p. 70; E. E. Reynolds, Thomas More & Erasmus, 1965, p. 25, and The Field is Won, The Life and Death of St Thomas More, 1968, p. 35.

- "Through the benefite of the river, a seate of more commoditie", observed Lambarde, in his Perambulation of Kent 1573, noted by Walter Thornbury and Edward Walford, Old and New London: A Narrative of Its History, Its People and Its Places 1893:238.

- Thornbury and Walford 1893:239.

- James Dowsing (3 June 2002). Forgotten Tudor palaces in the London area. London: Sunrise Press. ISBN 978-1-873876-15-2.

- "The Partners: Seely and Paget". English Heritage. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Eltham Palace". prop a scene. 2000. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "The History of Eltham Palace and Gardens". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012.

- Copping, Jasper (27 June 2009). "English Heritage reveals most haunted sites". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eltham Palace. |

.svg.png)