Chennai Lighthouse

The Chennai Lighthouse (Tamil: சென்னை கலங்கரை விளக்கம்), formerly the Madras Lighthouse, is a lighthouse facing the Bay of Bengal on the east coast of the Indian Subcontinent. It is a famous landmark on the Marina Beach in Chennai, India. It was built by the East Coast Constructions and Industries in 1976 replacing the old lighthouse in the northern direction. The lighthouse was opened in January 1977. It also houses the meteorological department. On 16 November 2013, it was reopened to visitors. It is one of the few lighthouses in the world with an elevator.[3][4] It is also the only lighthouse in India within the city limits.[1] It is also a green lighthouse, with a solar panel for power.[5]

| |

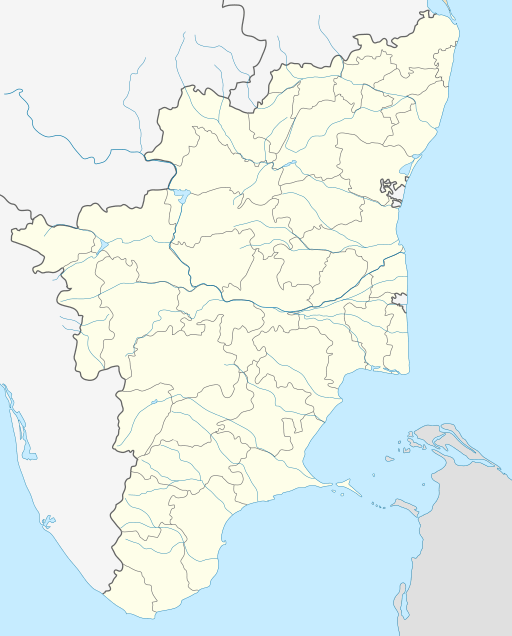

India Tamil Nadu | |

| |

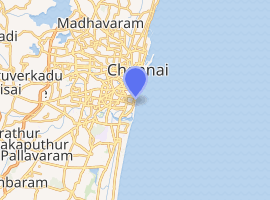

| Location | Kamarajar Salai, Marina Beach, Santhome, Chennai |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 13.039802°N 80.279575°E |

| Year first constructed | 1796 (first) 1844 (second) 1894 (third) |

| Year first lit | 1977 (current) built by East Coast Constructions |

| Foundation | reinforced concrete (Current location) |

| Construction | reinforced concrete |

| Tower shape | triangular prism with lantern and double gallery |

| Markings / pattern | red and white horizontal bands |

| Tower height | 45.72 metres (150.0 ft)[1] |

| Focal height | 57 metres (187 ft) above MSL |

| Original lens | 375 mm 3rd order revolving optic inside 2.5 m dia lantern house (BBT) |

| Intensity | 110 V 3000 W Incandescent Lamp |

| Range | 28 nautical miles (52 km; 32 mi) |

| Characteristic | Fl (2) W10s. |

| Admiralty number | F 0936 |

| NGA number | 27072 |

| ARLHS number | IND-010[2] |

| Managing agent | Directorate General of Lighhouses and Lightships, Government of India |

Location

The lighthouse is located on Kamarajar Salai (Beach Road) opposite the office of the Director General of Tamil Nadu Police and All India Radio's Chennai station. The lighthouse marks the end of the promenade on the northern half of the Marina Beach. It is also the junction where Kamarajar Salai, Santhome High Road and Dr. Radhakrishnan Salai meet. The lighthouse and the surrounding areas are served by the Light House MRTS station located nearby on Dr.Radhakrishnan Salai 13.0450°N 80.2768°E.

History

By the end of the 18th century, the Madras Presidency encompassed much of south India and also Ceylon. As its capital, the city of Madras served as the nerve centre of the sea trade controlled by the British East India Company. Ships approaching the shore of Madras after nightfall faced the risk of running aground on the shoals of Covelong (Kovalam) in the south and the sand-banks of Armagon and Pulicat in the north.[6]

The present lighthouse is the fourth lighthouse of Chennai. Before the end of the 18th century, when Madras was an open seashore, where goods were loaded and unloaded from boats, bonfire lit by fisherwomen was used to guide the menfolk to the shore. The arrangement of exhibiting light to assist British East India Company's vessels arriving at Madras and to enter the port during the 17th and 18th centuries is not known since no record is available. The first conventional lighthouse was proposed in 1795, the very year when the first census of the city was taken. In February 1795, maritime officials petitioned the British government to build a lighthouse at Fort St. George to serve as a navigational aid, allowing vessels to enter the open anchorage at all times. The request was approved and the steeple of St. Mary's Church was considered as the site for the new lighthouse. However, the proposal did not materialise due to opposition from the chaplains. Hence, the terrace of the officer's mess-cum-exchange building (the present day's Fort Museum) was chosen as the location for the new lighthouse, and the first lighthouse started functioning in 1796. It used a large oil-wick lantern to aid vessels approaching the port. Situated at 99 feet above sea level, it had 12 lamps fuelled by coconut oil.[6] Small country mirrors were used as reflectors.[7] The beam emanating from the lamp swept the sea as far as 25 miles from the shore. Signals were exchanged with the lighthouse by merchants on the ship, who would conduct all the transactions later in the Public Exchange Hall downstairs, which served as a meeting point for brokers, merchants, and commanders of ships. The first lighthouse functioned till 1841.[6]

In 1834, further to the petition by vice-admiral Sir John Gore about the necessity to have a more advanced lighthouse, the East India Company asked Capt. T. J. Smith of the Corps of Engineers, then on home leave in England, to suggest alternatives. When Capt. Smith returned to Madras in 1837, he brought with him a new apparatus. By then, ships, which were anchored in front of the Fort thus far, started anchoring off First Line Beach. The old lighthouse was therefore considered a location too far to the south. Incidentally, in the early 19th century, the area west of Fort St. George was the buffer zone between the Black Town and the fort which has come to be known as George Town. A fire in 1762 destroyed this area including two temples, the Chenna Kesavapperumal temple and the Chenna Malleeswarar temple that flourished in the area. The colonial government took possession of this land and facilitated the construction of these temples near the Flower Bazaar. It then considered the construction of a new lighthouse on this land.[6] This led to the choosing of a site on the Esplanade "between the Fort and the offices of Parry & Co" as the location for the new lighthouse.[7] Thus, the second lighthouse was erected during 1838–1844 on the north side of Fort St. George. Work began in 1838 on a granite column in the compound of the present High Court.[6] The column was designed by Smith, who had by then been promoted to Major. The stone for the construction was sourced from quarries in Pallavaram.[7] Work was completed in 1840[6] at a total cost of ₹ 60,000,[7] on which the wick lamp was shifted as the supply of the new equipment by Stone Chance, Birmingham was delayed.[6] The apparatus cost a further ₹ 15,000 and was of the most sophisticated kind for its times. On 9 October 1843, a public announcement was made that the new Madras Light was completed and it would be fully functional from 1 January 1844. Major Smith was asked to remain in charge until a team was trained to take over the handling of the equipment. He handed over charge to the master attendant of the Madras Harbour on 6 October 1845. The lighthouse had a full complement of staff comprising a superintendent, a deputy, a headman and six lascars. The monthly operational cost, inclusive of 208 measures of oil was ₹ 227 and 3 annas. It was to be the Madras Light for the next 50 years until 1894, when the British government felt the height of this lighthouse was not sufficient and decided to build a new, taller lighthouse,[6] leading to the High Court's tallest dome becoming the third lighthouse of Madras.[7] Today, this second lighthouse is under the watch of the Department of Archaeology as a protected monument.[6][8]

In 1886, during the reconstruction of the Madras Port after a cyclone, the port officer wrote to the Madras government alerting them of a possible threat to vessel traffic in the region from a Tripasore reef spotted around 40 miles south of Madras near Seven Pagodas (now known as Mamallapuram). The port officer then recommended that a lighthouse be installed to alert ships about the impending danger. Responding to this, the government shifted this lighthouse equipment with lantern onto the dome of the new High Court building. This became the third lighthouse of Chennai and was functioning from the tallest dome of the Madras High Court. It started functioning on 1 June 1894, with argand lamps and reflectors manufactured by Chance Bros, Birmingham which had originally been installed in the 160-ft-tall lighthouse tower. This lighthouse later became crucial for the development of the Madras port.

The lighthouse used kerosene to produce light with an intensity equivalent to that emitted by about 18,000 candles.[6] This remained one of the primary reasons for attracting the attention of the German warship SMS Emden during World War I. The lighthouse was the main target of the attack in which the High Court campus was bombed on 22 September 1914. The attack became part of the local folklore. A ballad in Tamil, published by Vijayapuram Sabhapati Pillai in 1914, goes:

To damage Fort and Light house too

Hurl they did some bombs ...

No damage, ha, no damage[6]

An improvement of equipment was introduced in 1927.[9] In the 1970s, the lighthouse department sought a site opposite the Madras University buildings to construct a new lighthouse. However, this request was rejected by the state government. Thus, a new lighthouse was instead built at the southern end of the Marina in 1976.[6] The new lighthouse was unveiled on 10 January 1977. An electrical lighthouse equipment manufactured by BBT, Paris was installed on the new tower, which maintains a range of 28 nautical miles for vessels and is one of the tallest lighthouses in the country.[9]

Coconut oil was considered the best fuel for a lighthouse lamp because it made the light burn bright in the lighthouse. Gas lights were used later followed by dischargeable lamps. In the beginning, the lighthouse lamp had a steady flame. When ships began to confuse this with city lights, it was decided to use a flickering light in lighthouses. The lighthouses at Chennai and Mamallapuram use dischargeable lamps, which rotate inside a bowl of mercury. In recent days, LED lights are preferred.

The Chennai Lighthouse District

The Chennai Lighthouse, along with 23 other lighthouses along the eastern, southern and western coast of the Indian peninsula, comes under the administration of the Chennai Lighthouse District. In accord with the Lighthouse Act of 1927 and the Lighthouse (Amendment) Act of 1985, the Chennai Lighthouse District comprises under its jurisdiction part of Kerala State which is south of latitude 9º00'N and state of Tamil Nadu, which is south of latitude 13º00'N and west of longitude 80º30'E and the union territory of Puducherry, which include the following lighthouses:[10]

%2C_Chennai.jpg)

1. Alleppey

2. Kovilthottam

3. Tangasseri Point (Quilon)

4. Anjengo

5. Vilinjam

6. Muttam Point

7. Kanyakumari (Cape Comorin)

8. Manappad Point

9. Pandiyan Tivu DGPS

10. Kilakkarai

11. Point Calimere

12. Kodikkarai

13. Ammapattinam DGPS

14. Pasipattinam

15. Rameswaram

16. Pamban

17. Nagapattinam DGPS

18. Karaikal

19. Porto Novo

20. Cuddalore Channel Buoyage

21. Pondicherry Lighthouse and DGPS

22. Mahabalipuram

23. Madras (Chennai)

24. Pulicat DGPS

The director general at the Directorate General of Lighthouses and Lightships located at Noida has under him or her four deputy director generals, namely, Jamnagar, Chennai, Kolkata and the headquarters. For administrative control, the entire coastline has been divided into seven districts having their regional headquarters at Jamanagar, Mumbai, Cochin, Chennai, Visakhapatnam, Kolkata and Port Blair. The Chennai Lighthouse District is administrated under the Regional Director (Chennai), who along with the Regional Director (Cochin) comes under the deputy director general (Chennai).[11] The Regional Office at Chennai provides information on the geographical region between Alleppey Lighthouse to Pulicat Lighthouse. The union government is planning to build three new lighthouses in the Chennai Lighthouse District at an estimated cost of ₹ 25 million each.[12][13]

The towers

The entrance channel tower (date unknown)

Located north of the port, the entrance channel tower is about 24 metres (79 ft) high with a focal plane of 26 metres (85 ft), flashing white, red and green lights, and the tower is visible only from a distance closer to the entrance channel. This tower was assigned an Admiralty number of F0938 and NGA number of 27074. This tower is still active.[14]

The first tower (1796–1844)

The first light at Madras is a lantern on the wall of the Fort St. George. With the growth of commercial activities of the English East India Company, the company built a lighthouse at the Fort in 1796. Functioning from the roof of the Officer's Mess, now housing the Fort Museum, it comprised a lantern with large oil-fed wicks.[5] The light has been inactive since 1844.

The second tower (1844–1894)

The second lighthouse was a tall granite Doric column erected in 1841 and is located within the compound of the Madras High Court to the north of Fort St. George. Work began in 1838 and was completed in 1843 at a cost of ₹ 75,000, and the lighthouse started functioning on 1 January 1844.[5] This round fluted stone tower with gallery is 38 metres (125 ft) tall.[5][15] Built on a base of 55-feet breadth, its column rises 84 feet with a tapering diameter—16 feet at the base and 11 feet at the top. The entire structure from base to tip has a height of 125 feet. The light was at 117 feet and was visible 20 miles into the sea. Illumination was by 15 "argand lamps with parabolic reflectors, arranged in three tiers." Unlike the earlier rotary model, it had a reciprocal type of light, with the ratio of bright-to-dark periods being 2:3 and with each unit of time being 24 seconds.[7] This tower was assigned an ARLHS number of IND-027. Given the inability of brick to withstand saline breeze of the sea, the surface of the tower was built with granite procured from quarries at Pallavaram. However, following the construction of the taller High Court building in 1892, mariners started having difficulty in identifying the tower during daytime. The tower became inactive since 1894 after the lighthouse was moved atop the dome of the main tower of the new High Court building. This Light House is renovated and inaugurated in September 2018.

The third tower (1894–1977)

The lantern from the second tower was moved to one of the tallest ornate towers of the Madras High Court building, which was constructed adjacent to the second tower in 1892. The lighthouse started functioning from 1 June 1894. According to I. C. R. Prasad's book Madras Lighthouse, the lantern room was erected on the gilded dome, with a cutting in the dome and the spiral staircase serving as entry to the top. The lighthouse used kerosene vapour lamps. The revolving light was supplied by Chance Brothers from Birmingham. The capillary lamp of this light was capable of producing 18,000 candelas power. It was assigned an ARLHS number of IND-026. This tower became inactive since 1977, after guiding British and Allied warships of both the world wars.[5]

The fourth tower (1977–present)

The present lighthouse is a triangular cylindrical, red-and-white-banded, concrete one with lantern and double gallery and is 11 stories high. The tower is attached to a three-story circular harbour-control building. The total height of the tower is 45.72 metres (150.0 ft) with the light source standing at a height of 57 metres (187 ft) from the mean sea level. The source consists of 440V 50 Hz main supply (with standby Genset), with a range of 28 nautical miles. It is functional since 10 January 1977.[5]

The base of the present lighthouse tower was damaged by the waves from the Indian Ocean tsunami of 26 December 2004, but there were no reported casualties.

Security

The ninth floor of the tower has a viewing gallery where steel welded mesh panels have been erected for safety. This has been done to avoid suicide attempts, which were witnessed in the past. The tenth floor has a high-security radar installed and is not open to public. The elevator in the lighthouse will take the visitors directly to the viewing gallery on the ninth floor, and visitors will not be given access to any other floors.[16]

The lighthouse was open to the public until the assassination of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, following which it was shut down over fears that it would be the target of an attack. It was re-opened for visitors on 14 November 2013.[17]

Developments

Chennai Lighthouse is one of the 13 lighthouses in India that are identified as heritage centres to portray maritime history of India.[18] A lighthouse museum has been planned at a cost of ₹ 50 million.[19][20] The union shipping ministry is planning to build museums, rooms, cafeteria, souvenir shop, viewers gallery, 4D cinema hall, gaming zone and aquarium at the Chennai lighthouse.[21][22] The heritage museum will showcase the history of marine navigation, where oil-bearing large wicks, kerosene lights, petroleum vapour, and electrical lamps used in the past will be on display.[16]

Directorate General of Lighthouses and Lightships has planned the remote control and automation of lighthouses in Cochin, Chennai, Visakhapatnam and Kolkata directorates at a cost of ₹ 304.5 million.[23] As a first step towards automation of lighthouses, Radone, an equipment that can detect radar signals from ships and helps captains identify the location, has been installed on most lighthouses. The automation of lighthouses in the Chennai Lighthouse District is estimated to cost about ₹ 50 million during the 11th Five-Year Plan.[24] The 22 lighthouses in the Chennai Lighthouse district will be monitored and controlled from conveniently located positions termed as Remote Control Stations (RCSs). These RCSs will be ultimately linked to Master Control Station, proposed to be located at Chennai for effective control.

See also

References

- TNN (22 September 2013). "Marina lighthouse to be opened for kids from Nov 14". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- "Chennai/Madras (New) Light". World List of Lights (WLOL). Amateur Radio Lighthouse Society. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Lighthouses in India". Lighthouse Depot. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- "Chennai lighthouse open to visitors after 22 years". NDTV. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Padmanabhan, Geeta (19 September 2017). "To the lighthouse". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Shivam, Pushkal (21 July 2013). "The glowing tale of Chennai's lighthouses". The Hindu. Chennai: The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Sriram, V. (8 October 2013). "170 years of a modern lighthouse". The Hindu. Chennai: The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Chandru, K. (26 November 2011). "Some thoughts around the Madras High Court". The Hindu. Chennai: The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Janardhanan, Arun (17 February 2011). "From an oil wick lamp to LEDs: A long way for seafaring tradition". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Directorate General of Lighthouses & Lightships (n.d.). "Lighthouse Act". Government of India, Ministry of Shipping. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Directorate General of Lighthouses & Lightships (n.d.). "Organisation Chart". Government of India, Ministry of Shipping. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "TN coast to soon boast of three new lighthouses". The New Indian Express. The New Indian Express. 13 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Automatic identification: Ministry to safeguard coastline". Maritime Gateway. Maritime Gateway. n.d. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Lighthouses of India: Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. n.d. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "High Court Building". Chennai-Directory.com. n.d. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Mariappan, Julie (24 September 2013). "Grille balcony to keep visitors safe at lighthouse". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- "Marina lighthouse reopened to visitors". The Hindu. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- "India: Project for Promotion of Tourism in Lighthouses". MarineBuzz.com. MarineBuzz.com. 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "New project to promote tourism in lighthouses". Business Line. Chennai: The Hindu. 12 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Modernization programme for Aguada lighthouse". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. 13 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Ayyappan, V. (17 February 2011). "Now, holiday at a lighthouse". The Times of India. Chennai: The Times Group. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Lighthouses across the Country to be Developed as Tourist Attractions for Maritime History of India". Rang 7. 14 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Directorate General of Lighthouses & Lightships (n.d.). "New Projects". Government of India, Ministry of Shipping. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "The Working Group Report on Shipping and Inland Water Transport for the Eleventh Five Year Plan" (PDF). Working Group Report on Shipping and IWT. Planning Commission, Government of India. n.d. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

External links

- Chennai Lighthouse in Lighthouse Digest's Lighthouse Explorer Database

- Photo of the original lighthouse

- The Hindu – The second longest beach?

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chennai Lighthouse. |