Primary nutritional groups

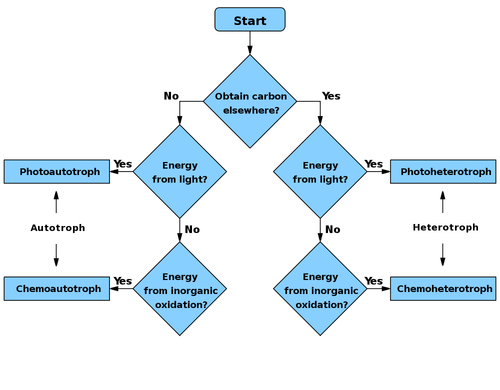

Primary nutritional groups are groups of organisms, divided in relation to the nutrition mode according to the sources of energy and carbon, needed for living, growth and reproduction. The sources of energy can be light or chemical compounds; the sources of carbon can be of organic or inorganic origin.[1]

The terms aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration and fermentation (substrate-level phosphorylation) do not refer to primary nutritional groups, but simply reflect the different use of possible electron acceptors in particular organisms, such as O2 in aerobic respiration, or nitrate (NO3−), sulfate (SO42−) or fumarate in anaerobic respiration, or various metabolic intermediates in fermentation.

Primary sources of energy

Phototrophs absorb light in photoreceptors and transform it into chemical energy.

Chemotrophs release bond energy from chemical compounds.[2]

The freed energy is stored as potential energy in ATP, carbohydrates, or proteins. Eventually, the energy is used for life processes such as moving, growth and reproduction.

Plants and some bacteria can alternate between phototrophy and chemotrophy, depending on the availability of light.

Primary sources of reducing equivalents

Organotrophs use organic compounds as electron/hydrogen donors.

Lithotrophs use inorganic compounds as electron/hydrogen donors.

The electrons or hydrogen atoms from reducing equivalents (electron donors) are needed by both phototrophs and chemotrophs in reduction-oxidation reactions that transfer energy in the anabolic processes of ATP synthesis (in heterotrophs) or biosynthesis (in autotrophs). The electron or hydrogen donors are taken up from the environment.

Organotrophic organisms are often also heterotrophic, using organic compounds as sources of both electrons and carbon. Similarly, lithotrophic organisms are often also autotrophic, using inorganic sources of electrons and CO2 as their inorganic carbon source.

Some lithotrophic bacteria can utilize diverse sources of electrons, depending on the availability of possible donors.

The organic or inorganic substances (e.g., oxygen) used as electron acceptors needed in the catabolic processes of aerobic or anaerobic respiration and fermentation are not taken into account here.

For example, plants are lithotrophs because they use water as their electron donor for biosynthesis. Animals are organotrophs because they use organic compounds as electron donors to synthesize ATP (plants also do this, but this is not taken into account). Both use oxygen in respiration as electron acceptor and the main source of energy,[2] but this character is not used to define them as lithotrophs.

Primary sources of carbon

Heterotrophs metabolize organic compounds to obtain carbon for growth and development.

Autotrophs use carbon dioxide (CO2) as their source of carbon.

Energy and carbon

| Energy source | Light | photo- | -troph | ||

| Molecules | chemo- | ||||

| Electron donor | Organic compounds | organo- | |||

| Inorganic compounds | litho- | ||||

| Carbon source | Organic compounds | hetero- | |||

| Carbon dioxide | auto- | ||||

A chemoorganoheterotrophic organism is one that requires organic substrates to get its carbon for growth and development, and that obtains its energy from the decomposition, often an oxidation,[2] of an organic compound. This group of organisms may be further subdivided according to what kind of organic substrate and compound they use. Decomposers are examples of chemoorganoheterotrophs which obtain carbon and electrons or hydrogen from dead organic matter. Herbivores and carnivores are examples of organisms that obtain carbon and electrons or hydrogen from living organic matter.

Chemoorganotrophs are organisms which use the chemical bonds in organic compounds or O2[2] as their energy source and obtain electrons or hydrogen from the organic compounds, including sugars (i.e. glucose), fats and proteins.[3] Chemoheterotrophs also obtain the carbon atoms that they need for cellular function from these organic compounds.

All animals are chemoheterotrophs (meaning they oxidize chemical compounds as a source of energy and carbon), as are fungi, protozoa, and some bacteria. The important differentiation amongst this group is that chemoorganotrophs oxidize only organic compounds while chemolithotrophs instead use oxidation of inorganic compounds as a source of energy.[4]

Primary metabolism table

The following table gives some examples for each nutritional group:[5][6][7][8]

| Energy source |

Electron/ H-atom donor |

Carbon source | Name | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun Light Photo- |

Organic -organo- |

Organic -heterotroph |

Photoorganoheterotroph | Some bacteria: Rhodobacter, Heliobacterium, some green non-sulfur bacteria[9] |

| Carbon dioxide -autotroph |

Photoorganoautotroph | |||

| Inorganic -litho-* |

Organic -heterotroph |

Photolithoheterotroph | Purple non-sulfur bacteria | |

| Carbon dioxide -autotroph |

Photolithoautotroph | Some bacteria (cyanobacteria), some eukaryotes (eukaryotic algae, land plants). Photosynthesis. | ||

| Breaking Chemical Compounds Chemo- |

Organic -organo- |

Organic -heterotroph |

Chemoorganoheterotroph | Predatory, parasitic, and saprophytic prokaryotes. Some eukaryotes (heterotrophic protists, fungi, animals) |

| Carbon dioxide -autotroph |

Chemoorganoautotroph | Some archaea (anaerobic methanotrophic archaea).[10] Chemosynthesis, synthetically autotrophic Escherichia coli bacteria[11] and Pichia pastoris yeast.[12] | ||

| Inorganic -litho-* |

Organic -heterotroph |

Chemolithoheterotroph | Some bacteria (Oceanithermus profundus)[13] | |

| Carbon dioxide -autotroph |

Chemolithoautotroph | Some bacteria (Nitrobacter), some archaea (Methanobacteria). Chemosynthesis. |

- Some authors use -hydro- when the source is water.

Mixotrophs

Some, usually unicellular, organisms can switch between different metabolic modes, for example between photoautotrophy, photoheterotrophy, and chemoheterotrophy in Chroococcales [14] Such mixotrophic organisms may dominate their habitat, due to their capability to use more resources than either photoautotrophic or organoheterotrophic organisms.[15]

Examples

All sorts of combinations may exist in nature, but some are more common than others. For example, most plants are photolithoautotrophic, since they use light as an energy source, water as electron donor, and CO2 as a carbon source. All animals and fungi are chemoorganoheterotrophic, since they use chemical energy sources (organic substances and O2)[2] and organic molecules as both electron/hydrogen donors and carbon sources. Some eukaryotic microorganisms, however, are not limited to just one nutritional mode. For example, some algae live photoautotrophically in the light, but shift to chemoorganoheterotrophy in the dark. Even higher plants retained their ability to respire heterotrophically on starch at night which had been synthesised phototrophically during the day.

Prokaryotes show a great diversity of nutritional categories.[16] For example, cyanobacteria and many purple sulfur bacteria can be photolithoautotrophic, using light for energy, H2O or sulfide as electron/hydrogen donors, and CO2 as carbon source, whereas green non-sulfur bacteria can be photoorganoheterotrophic, using organic molecules as both electron/hydrogen donors and carbon sources.[9][16] Many bacteria are chemoorganoheterotrophic, using organic molecules as energy, electron/hydrogen and carbon sources.[9] Some bacteria are limited to only one nutritional group, whereas others are facultative and switch from one mode to the other, depending on the nutrient sources available.[16] Sulfur-oxidizing, iron, and anammox bacteria as well as methanogens are chemolithoautotrophs, using inorganic energy, electron, and carbon sources. Chemolithoheterotrophs are rare because heterotrophy implies the availability of organic substrates, which can also serve as easy electron sources, making lithotrophy unnecessary. Photoorganoautotrophs are uncommon since their organic source of electrons/hydrogens would provide an easy carbon source, resulting in heterotrophy.

Synthetic biology efforts enabled the transformation of the trophic mode of two model microorganisms from heterotrophy to chemoorganoautotrophy:

- Escherichia coli was genetically engineered and then evolved in the laboratory to use CO2 as the sole carbon source while using the one-carbon molecule formate as the source of electrons.[11]

- The methylotrophic Pichia pastoris yeast was genetically engineered to use CO2 as the carbon source instead of methanol, while the latter remained the source of electrons for the cells.[12]

See also

Notes and references

- Eiler A (December 2006). "Evidence for the ubiquity of mixotrophic bacteria in the upper ocean: implications and consequences". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (12): 7431–7. doi:10.1128/AEM.01559-06. PMC 1694265. PMID 17028233.

Table 1: Definitions of metabolic strategies to obtain carbon and energy

- Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2020). "Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics” ACS Omega 5: 2221-2233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03352

- Todar K (2009). "Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology". Nutrition and Growth of Bacteria. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

- Kelly DP, Mason J, Wood A (1987). "Energy Metabolism in Chemolithotrophs". In van Verseveld HW, Duine JA (eds.). Microbial Growth on C1 Compounds. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 186–187. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-3539-6_23. ISBN 978-94-010-8082-8.

- Lwoff A, Van Niel CB, Ryan TF, Tatum EL (1946). "Nomenclature of nutritional types of microorganisms" (PDF). Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quantit. Biol (5th ed.). 11: 302–303.

- Andrews JH (1991). Comparative Ecology of Microorganisms and Macroorganisms. Berlin: Springer Verlag. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-387-97439-2.

- Yafremava LS, Wielgos M, Thomas S, Nasir A, Wang M, Mittenthal JE, Caetano-Anollés G (2013). "A general framework of persistence strategies for biological systems helps explain domains of life". Frontiers in Genetics. 4: 16. doi:10.3389/fgene.2013.00016. PMC 3580334. PMID 23443991.

- Margulis L, McKhann HI, Olendzenski L, eds. (1993). Illustrated Glossary of Protoctista: Vocabulary of the Algae, Apicomplexa, Ciliates, Foraminifera, Microspora, Water Molds, Slime Molds, and the Other Protoctists. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. xxv. ISBN 978-0-86720-081-2.

- Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", 3rd edition, W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1319017637

- Kellermann MY, Wegener G, Elvert M, Yoshinaga MY, Lin YS, Holler T, et al. (November 2012). "Autotrophy as a predominant mode of carbon fixation in anaerobic methane-oxidizing microbial communities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (47): 19321–6. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10919321K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208795109. PMC 3511159. PMID 23129626.

- Gleizer S, Ben-Nissan R, Bar-On YM, Antonovsky N, Noor E, Zohar Y, et al. (November 2019). "2". Cell. 179 (6): 1255–1263.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.009. PMC 6904909. PMID 31778652.

- Gassler T, Sauer M, Gasser B, Egermeier M, Troyer C, Causon T, et al. (December 2019). "2". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (2): 210–216. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0363-0. PMC 7008030. PMID 31844294.

- Miroshnichenko ML, L'Haridon S, Jeanthon C, Antipov AN, Kostrikina NA, Tindall BJ, et al. (May 2003). "Oceanithermus profundus gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic, microaerophilic, facultatively chemolithoheterotrophic bacterium from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (Pt 3): 747–52. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02367-0. PMID 12807196.

- Rippka R (March 1972). "Photoheterotrophy and chemoheterotrophy among unicellular blue-green algae". Archives of Microbiology. 87 (1): 93–98. doi:10.1007/BF00424781.

- Eiler A (December 2006). "Evidence for the ubiquity of mixotrophic bacteria in the upper ocean: implications and consequences". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (12): 7431–7. doi:10.1128/AEM.01559-06. PMC 1694265. PMID 17028233.

- Tang, K.-H., Tang, Y. J., Blankenship, R. E. (2011). "Carbon metabolic pathways in phototrophic bacteria and their broader evolutionary implications" Frontiers in Microbiology 2: Art. 165. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/micb.2011.00165