Oscar Straus (politician)

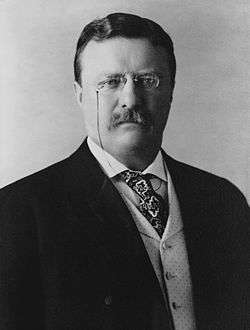

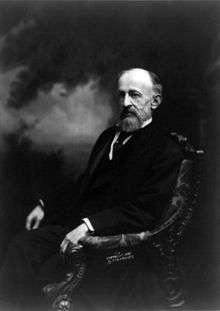

Oscar Solomon Straus (December 23, 1850 – May 3, 1926) was United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor under President Theodore Roosevelt from 1906 to 1909. Straus was the first Jewish United States Cabinet Secretary.[1]

Oscar Straus | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office October 4, 1909 – September 3, 1910 | |

| President | William Taft |

| Preceded by | John Leishman |

| Succeeded by | William Rockhill |

| In office October 15, 1898 – December 20, 1899 Minister | |

| President | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | James Angell |

| Succeeded by | John Leishman |

| In office July 1, 1887 – June 16, 1889 Envoy | |

| President | Grover Cleveland Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | Samuel S. Cox |

| Succeeded by | Solomon Hirsch |

| 3rd United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor | |

| In office December 17, 1906 – March 5, 1909 | |

| President | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Victor H. Metcalf |

| Succeeded by | Charles Nagel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Oscar Solomon Straus December 23, 1850 Otterberg, Bavaria, Germany |

| Died | May 3, 1926 (aged 75) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Other political affiliations | Independence Progressive |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Straus |

| Education | Columbia University (BA, LLB) |

Early life and education

He was born in Otterberg, Germany. He emigrated with his parents to the United States, and settled in Talbotton, Georgia. At the close of the Civil War he moved to New York City where he graduated from Columbia College in 1871 and Columbia Law School in 1873. He practiced law until 1881, and then became a merchant, retaining his interest in literature.[2]

Diplomatic career

He first served as United States Minister to the Ottoman Empire from 1887 to 1889 and again from 1898 to 1899. John Hay, the American Secretary of State, asked the Jewish American ambassador to Ottoman Turkey, Oscar Strauss, in 1899 to approach Sultan Abdul Hamid II to request that the Sultan write a letter to the Moro Sulu Muslims of the Sulu Sultanate in the Philippines telling them to submit to American suzerainty and American military rule; the Sultan obliged them and wrote the letter which was sent to Sulu via Mecca where 2 Sulu chiefs brought it home to Sulu. It was deemed successful, as the Sulu Mohammedans . . . refused to join the insurrectionists and had placed themselves under the control of our army, thereby recognizing American sovereignty.[3][4] The Ottoman Sultan used his position as caliph to order the Sulu Sultan not to resist and not fight the Americans when they came subjected to American control.[5] President McKinley did not mention Turkey's role in the pacification of the Sulu Moros in his address to the first session of the Fifty-sixth Congress in December 1899 since the agreement with the Sultan of Sulu was not submitted to the Senate until December 18.[6] Despite Sultan Abdulhamid's "pan-Islamic" ideology, he readily acceded to Oscar S. Straus' request for help in telling the Sulu Muslims to not resist America since he felt no need to cause hostilities between the West and Muslims.[7] Collaboration between the American military and Sulu sultanate was due to the Sulu Sultan being persuaded by the Ottoman Sultan.[8] John P. Finley wrote that: After due consideration of these facts, the Sultan, as Caliph caused a message to be sent to the Mohammedans of the Philippine Islands forbidding them to enter into any hostilities against the Americans, inasmuch as no interference with their religion would be allowed under American rule. As the Moros have never asked more than that, it is not surprising, that they refused all overtures made, by Aguinaldo's agents, at the time of the Filipino insurrection. President McKinley sent a personal letter of thanks to Mr. Straus for the excellent work he had done, and said, its accomplishment had saved the United States at least twenty thousand troops in the field. If the reader will pause to consider what this means in men and also the millions in money, he will appreciate this wonderful piece of diplomacy, in averting a holy war.[9][10] Abdulhamid in his position as Caliph was approached by the Americans to help them deal with Muslims during their war in the Philippines[11] and the Muslim people of the area obeyed the order to help the Americans which was sent by Abdulhamid.[12][13][14]

The Moro Rebellion then broke out in 1904 with war raging between the Americans and Moro Muslims and atrocities committed against Moro Muslim women and children such as the Moro Crater Massacre.

On January 14, 1902, he was named a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague to fill the place left vacant by the death of ex-President Benjamin Harrison.[15]

Career as Secretary of Commerce and Labor and Ambassador to Ottoman Empire

In December 1906, Straus became the United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor under President Theodore Roosevelt. This position also placed him in charge of the United States Bureau of Immigration. During his tenure, Straus ordered immigration inspectors to work closely with local police and the United States Secret Service to find, arrest and deport immigrants with Anarchist political beliefs under the terms of the Anarchist Exclusion Act.[16]

Straus left the Commerce Department in 1909 when William Howard Taft became president. Taft appointed him U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire 1909-1910. During the Presidency of William Howard Taft, an American strategy was to become involved in business transactions rather than military confrontations, a policy known as Dollar Diplomacy. It failed with respect to the Ottoman Empire because of opposition from ambassador Straus and to Turkish vacillation under pressure from the entrenched European powers who did not wish to see American competition. American trade remained a minor factor.[17]

In 1912, he ran unsuccessfully for Governor of New York on the Progressive and Independence League tickets. In 1915, he became chairman of the public service commission of New York State.[18]

He was president of the American Jewish Historical Society.[18] He is buried at Beth El Cemetery in Ridgewood, New York.

Family

The Straus family had several influential members including Straus's grandson Roger W. Straus, Jr., who started the publishing company of Farrar, Straus and Giroux; his brother, Isidor Straus, who perished aboard the RMS Titanic in 1912, served as a representative from New York City's 15th District, and was co-owner of the department store R. H. Macy & Co. along with another brother, Nathan; and nephew Jesse Isidor Straus, confidant of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Ambassador to France from 1933 to 1936.

In 1882, Strauss married Sarah Lavanburg.[19] They had three children: Mildred Straus Schafer (born 1883), Aline Straus Hockstader (born 1889), and Roger Williams Straus (born 1891).[20][21]

Legacy

Washington, D.C., commemorates the achievements of this famous Jewish-German-American statesman in the Oscar Straus Memorial.

Works

- The Origin of the Republican Form of Government in the United States (1886)

- Roger Williams, the Pioneer of Religious Liberty (1894)

- The Development of Religious Liberty in the United States (1896)

- Reform in the Consular Service (1897)

- United States Doctrine of Citizenship (1901)

- Our Diplomacy with Reference to our Foreign Service (1902)

- The American Spirit (1913)

- Under Four Administrations, his memoirs (1922)

References

- "Oscar S. Straus (1906–1909): Secretary of Commerce and Labor" Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Miller Center, University of Virginia

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Kemal H. Karpat (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. Oxford University Press. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-0-19-513618-0.

- Kemal H. Karpat (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. Oxford University Press. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-0-19-513618-0.

- Moshe Yegar (1 January 2002). Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar. Lexington Books. pp. 397–. ISBN 978-0-7391-0356-2.

- Political Science Quarterly. Academy of Political Science. 1904. pp. 22–.

Straus Sulu Ottoman.

- Mustafa Akyol (18 July 2011). Islam without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty. W. W. Norton. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-393-07086-6.

- J. Robert Moskin (19 November 2013). American Statecraft: The Story of the U.S. Foreign Service. St. Martin's Press. pp. 204–. ISBN 978-1-250-03745-9.

- George Hubbard Blakeslee; Granville Stanley Hall; Harry Elmer Barnes (1915). The Journal of International Relations. Clark University. pp. 358–.

- The Journal of Race Development. Clark University. 1915. pp. 358–.

- Idris Bal (2004). Turkish Foreign Policy in Post Cold War Era. Universal-Publishers. pp. 405–. ISBN 978-1-58112-423-1.

- Idris Bal (2004). Turkish Foreign Policy in Post Cold War Era. Universal-Publishers. pp. 406–. ISBN 978-1-58112-423-1.

- Akyol, Mustafa (December 26, 2006). "Mustafa Akyol: Remembering Abdul Hamid II, a pro-American caliph". Weekly Standard – via History News Network.

- ERASMUS (July 26, 2016). "Why European Islam's current problems might reflect a 100-year-old mistake". The Economist.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- "To Drive Anarchists Out of the Country," New York Times, March 4, 1908, pp. 1-2.

- Naomi W. Cohen, "Ambassador Straus in Turkey, 1909-1910: A Note on Dollar Diplomacy." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 45.4 (1959) online

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- "Oscar S. Straus, Statesman and Philanthropist, Dies". Jewish Telegraph Agency. May 4, 1926. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- "Sarah Lavanburg Straus 1861 – 1945". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- "Morse, Mildred Hockstader Tiny". New York Times. July 9, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

External links

- Straus Historical Society

- Works by Oscar Straus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Oscar Straus at Internet Archive

- Oscar Straus at Find a Grave

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

Progressive Nominee for Governor of New York 1912 |

Succeeded by Frederick M. Davenport |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Samuel S. Cox |

United States Envoy to the Ottoman Empire 1887–1889 |

Succeeded by Solomon Hirsch |

| Preceded by James Angell |

United States Minister to the Ottoman Empire 1898–1899 |

Succeeded by John Leishman |

| Preceded by John Leishman |

United States Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire 1909–1910 |

Succeeded by William Rockhill |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Victor H. Metcalf |

United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor 1906–1909 |

Succeeded by Charles Nagel |