Category theory

Category theory[1] formalizes mathematical structure and its concepts in terms of a labeled directed graph called a category, whose nodes are called objects, and whose labelled directed edges are called arrows (or morphisms). A category has two basic properties: the ability to compose the arrows associatively, and the existence of an identity arrow for each object. The language of category theory has been used to formalize concepts of other high-level abstractions such as sets, rings, and groups. Informally, category theory is a general theory of functions.

Several terms used in category theory, including the term "morphism", are used differently from their uses in the rest of mathematics. In category theory, morphisms obey conditions specific to category theory itself.

Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane introduced the concepts of categories, functors, and natural transformations in 1942–45 in their study of algebraic topology, with the goal of understanding the processes that preserve mathematical structure.

Category theory has practical applications in programming language theory, for example the usage of monads in functional programming. It may also be used as an axiomatic foundation for mathematics, as an alternative to set theory and other proposed foundations.

Basic concepts

Categories represent abstractions of other mathematical concepts. Many areas of mathematics can be formalised by category theory as categories. Hence category theory uses abstraction to make it possible to state and prove many intricate and subtle mathematical results in these fields in a much simpler way.[2]

A basic example of a category is the category of sets, where the objects are sets and the arrows are functions from one set to another. However, the objects of a category need not be sets, and the arrows need not be functions. Any way of formalising a mathematical concept such that it meets the basic conditions on the behaviour of objects and arrows is a valid category—and all the results of category theory apply to it.

The "arrows" of category theory are often said to represent a process connecting two objects, or in many cases a "structure-preserving" transformation connecting two objects. There are, however, many applications where much more abstract concepts are represented by objects and morphisms. The most important property of the arrows is that they can be "composed", in other words, arranged in a sequence to form a new arrow.

Applications of categories

Categories now appear in many branches of mathematics, some areas of theoretical computer science where they can correspond to types or to database schemas, and mathematical physics where they can be used to describe vector spaces.[3] Probably the first application of category theory outside pure mathematics was the "metabolism-repair" model of autonomous living organisms by Robert Rosen.[4]

Utility

Categories, objects, and morphisms

The study of categories is an attempt to axiomatically capture what is commonly found in various classes of related mathematical structures by relating them to the structure-preserving functions between them. A systematic study of category theory then allows us to prove general results about any of these types of mathematical structures from the axioms of a category.

Consider the following example. The class Grp of groups consists of all objects having a "group structure". One can proceed to prove theorems about groups by making logical deductions from the set of axioms defining groups. For example, it is immediately proven from the axioms that the identity element of a group is unique.

Instead of focusing merely on the individual objects (e.g., groups) possessing a given structure, category theory emphasizes the morphisms – the structure-preserving mappings – between these objects; by studying these morphisms, one is able to learn more about the structure of the objects. In the case of groups, the morphisms are the group homomorphisms. A group homomorphism between two groups "preserves the group structure" in a precise sense; informally it is a "process" taking one group to another, in a way that carries along information about the structure of the first group into the second group. The study of group homomorphisms then provides a tool for studying general properties of groups and consequences of the group axioms.

A similar type of investigation occurs in many mathematical theories, such as the study of continuous maps (morphisms) between topological spaces in topology (the associated category is called Top), and the study of smooth functions (morphisms) in manifold theory.

Not all categories arise as "structure preserving (set) functions", however; the standard example is the category of homotopies between pointed topological spaces.

If one axiomatizes relations instead of functions, one obtains the theory of allegories.

Functors

A category is itself a type of mathematical structure, so we can look for "processes" which preserve this structure in some sense; such a process is called a functor.

Diagram chasing is a visual method of arguing with abstract "arrows" joined in diagrams. Functors are represented by arrows between categories, subject to specific defining commutativity conditions. Functors can define (construct) categorical diagrams and sequences (viz. Mitchell, 1965). A functor associates to every object of one category an object of another category, and to every morphism in the first category a morphism in the second.

As a result, this defines a category of categories and functors – the objects are categories, and the morphisms (between categories) are functors.

Studying categories and functors is not just studying a class of mathematical structures and the morphisms between them but rather the relationships between various classes of mathematical structures. This fundamental idea first surfaced in algebraic topology. Difficult topological questions can be translated into algebraic questions which are often easier to solve. Basic constructions, such as the fundamental group or the fundamental groupoid of a topological space, can be expressed as functors to the category of groupoids in this way, and the concept is pervasive in algebra and its applications.

Natural transformations

Abstracting yet again, some diagrammatic and/or sequential constructions are often "naturally related" – a vague notion, at first sight. This leads to the clarifying concept of natural transformation, a way to "map" one functor to another. Many important constructions in mathematics can be studied in this context. "Naturality" is a principle, like general covariance in physics, that cuts deeper than is initially apparent. An arrow between two functors is a natural transformation when it is subject to certain naturality or commutativity conditions.

Functors and natural transformations ('naturality') are the key concepts in category theory.[5]

Categories, objects, and morphisms

Categories

A category C consists of the following three mathematical entities:

- A class ob(C), whose elements are called objects;

- A class hom(C), whose elements are called morphisms or maps or arrows. Each morphism f has a source object a and target object b.

The expression f : a → b, would be verbally stated as "f is a morphism from a to b".

The expression hom(a, b) – alternatively expressed as homC(a, b), mor(a, b), or C(a, b) – denotes the hom-class of all morphisms from a to b. - A binary operation ∘, called composition of morphisms, such that for any three objects a, b, and c, we have ∘ : hom(b, c) × hom(a, b) → hom(a, c). The composition of f : a → b and g : b → c is written as g ∘ f or gf,[lower-alpha 1] governed by two axioms:

- Associativity: If f : a → b, g : b → c and h : c → d then h ∘ (g ∘ f) = (h ∘ g) ∘ f, and

- Identity: For every object x, there exists a morphism 1x : x → x called the identity morphism for x, such that for every morphism f : a → b, we have 1b ∘ f = f = f ∘ 1a.

- From the axioms, it can be proved that there is exactly one identity morphism for every object. Some authors deviate from the definition just given by identifying each object with its identity morphism.

Morphisms

Relations among morphisms (such as fg = h) are often depicted using commutative diagrams, with "points" (corners) representing objects and "arrows" representing morphisms.

Morphisms can have any of the following properties. A morphism f : a → b is a:

- monomorphism (or monic) if f ∘ g1 = f ∘ g2 implies g1 = g2 for all morphisms g1, g2 : x → a.

- epimorphism (or epic) if g1 ∘ f = g2 ∘ f implies g1 = g2 for all morphisms g1, g2 : b → x.

- bimorphism if f is both epic and monic.

- isomorphism if there exists a morphism g : b → a such that f ∘ g = 1b and g ∘ f = 1a.[lower-alpha 2]

- endomorphism if a = b. end(a) denotes the class of endomorphisms of a.

- automorphism if f is both an endomorphism and an isomorphism. aut(a) denotes the class of automorphisms of a.

- retraction if a right inverse of f exists, i.e. if there exists a morphism g : b → a with f ∘ g = 1b.

- section if a left inverse of f exists, i.e. if there exists a morphism g : b → a with g ∘ f = 1a.

Every retraction is an epimorphism, and every section is a monomorphism. Furthermore, the following three statements are equivalent:

- f is a monomorphism and a retraction;

- f is an epimorphism and a section;

- f is an isomorphism.

Functors

Functors are structure-preserving maps between categories. They can be thought of as morphisms in the category of all (small) categories.

A (covariant) functor F from a category C to a category D, written F : C → D, consists of:

- for each object x in C, an object F(x) in D; and

- for each morphism f : x → y in C, a morphism F(f) : F(x) → F(y),

such that the following two properties hold:

- For every object x in C, F(1x) = 1F(x);

- For all morphisms f : x → y and g : y → z, F(g ∘ f) = F(g) ∘ F(f).

A contravariant functor F: C → D is like a covariant functor, except that it "turns morphisms around" ("reverses all the arrows"). More specifically, every morphism f : x → y in C must be assigned to a morphism F(f) : F(y) → F(x) in D. In other words, a contravariant functor acts as a covariant functor from the opposite category Cop to D.

Natural transformations

A natural transformation is a relation between two functors. Functors often describe "natural constructions" and natural transformations then describe "natural homomorphisms" between two such constructions. Sometimes two quite different constructions yield "the same" result; this is expressed by a natural isomorphism between the two functors.

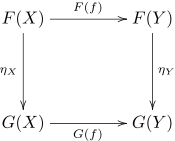

If F and G are (covariant) functors between the categories C and D, then a natural transformation η from F to G associates to every object X in C a morphism ηX : F(X) → G(X) in D such that for every morphism f : X → Y in C, we have ηY ∘ F(f) = G(f) ∘ ηX; this means that the following diagram is commutative:

The two functors F and G are called naturally isomorphic if there exists a natural transformation from F to G such that ηX is an isomorphism for every object X in C.

Other concepts

Universal constructions, limits, and colimits

Using the language of category theory, many areas of mathematical study can be categorized. Categories include sets, groups and topologies.

Each category is distinguished by properties that all its objects have in common, such as the empty set or the product of two topologies, yet in the definition of a category, objects are considered atomic, i.e., we do not know whether an object A is a set, a topology, or any other abstract concept. Hence, the challenge is to define special objects without referring to the internal structure of those objects. To define the empty set without referring to elements, or the product topology without referring to open sets, one can characterize these objects in terms of their relations to other objects, as given by the morphisms of the respective categories. Thus, the task is to find universal properties that uniquely determine the objects of interest.

Numerous important constructions can be described in a purely categorical way if the category limit can be developed and dualized to yield the notion of a colimit.

Equivalent categories

It is a natural question to ask: under which conditions can two categories be considered essentially the same, in the sense that theorems about one category can readily be transformed into theorems about the other category? The major tool one employs to describe such a situation is called equivalence of categories, which is given by appropriate functors between two categories. Categorical equivalence has found numerous applications in mathematics.

Further concepts and results

The definitions of categories and functors provide only the very basics of categorical algebra; additional important topics are listed below. Although there are strong interrelations between all of these topics, the given order can be considered as a guideline for further reading.

- The functor category DC has as objects the functors from C to D and as morphisms the natural transformations of such functors. The Yoneda lemma is one of the most famous basic results of category theory; it describes representable functors in functor categories.

- Duality: Every statement, theorem, or definition in category theory has a dual which is essentially obtained by "reversing all the arrows". If one statement is true in a category C then its dual is true in the dual category Cop. This duality, which is transparent at the level of category theory, is often obscured in applications and can lead to surprising relationships.

- Adjoint functors: A functor can be left (or right) adjoint to another functor that maps in the opposite direction. Such a pair of adjoint functors typically arises from a construction defined by a universal property; this can be seen as a more abstract and powerful view on universal properties.

Higher-dimensional categories

Many of the above concepts, especially equivalence of categories, adjoint functor pairs, and functor categories, can be situated into the context of higher-dimensional categories. Briefly, if we consider a morphism between two objects as a "process taking us from one object to another", then higher-dimensional categories allow us to profitably generalize this by considering "higher-dimensional processes".

For example, a (strict) 2-category is a category together with "morphisms between morphisms", i.e., processes which allow us to transform one morphism into another. We can then "compose" these "bimorphisms" both horizontally and vertically, and we require a 2-dimensional "exchange law" to hold, relating the two composition laws. In this context, the standard example is Cat, the 2-category of all (small) categories, and in this example, bimorphisms of morphisms are simply natural transformations of morphisms in the usual sense. Another basic example is to consider a 2-category with a single object; these are essentially monoidal categories. Bicategories are a weaker notion of 2-dimensional categories in which the composition of morphisms is not strictly associative, but only associative "up to" an isomorphism.

This process can be extended for all natural numbers n, and these are called n-categories. There is even a notion of ω-category corresponding to the ordinal number ω.

Higher-dimensional categories are part of the broader mathematical field of higher-dimensional algebra, a concept introduced by Ronald Brown. For a conversational introduction to these ideas, see John Baez, 'A Tale of n-categories' (1996).

Historical notes

It should be observed first that the whole concept of a category is essentially an auxiliary one; our basic concepts are essentially those of a functor and of a natural transformation [...]

In 1942–45, Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane introduced categories, functors, and natural transformations as part of their work in topology, especially algebraic topology. Their work was an important part of the transition from intuitive and geometric homology to homological algebra. Eilenberg and Mac Lane later wrote that their goal was to understand natural transformations. That required defining functors, which required categories.

Stanislaw Ulam, and some writing on his behalf, have claimed that related ideas were current in the late 1930s in Poland. Eilenberg was Polish, and studied mathematics in Poland in the 1930s. Category theory is also, in some sense, a continuation of the work of Emmy Noether (one of Mac Lane's teachers) in formalizing abstract processes; Noether realized that understanding a type of mathematical structure requires understanding the processes that preserve that structure (homomorphisms). Eilenberg and Mac Lane introduced categories for understanding and formalizing the processes (functors) that relate topological structures to algebraic structures (topological invariants) that characterize them.

Category theory was originally introduced for the need of homological algebra, and widely extended for the need of modern algebraic geometry (scheme theory). Category theory may be viewed as an extension of universal algebra, as the latter studies algebraic structures, and the former applies to any kind of mathematical structure and studies also the relationships between structures of different nature. For this reason, it is used throughout mathematics. Applications to mathematical logic and semantics (categorical abstract machine) came later.

Certain categories called topoi (singular topos) can even serve as an alternative to axiomatic set theory as a foundation of mathematics. A topos can also be considered as a specific type of category with two additional topos axioms. These foundational applications of category theory have been worked out in fair detail as a basis for, and justification of, constructive mathematics. Topos theory is a form of abstract sheaf theory, with geometric origins, and leads to ideas such as pointless topology.

Categorical logic is now a well-defined field based on type theory for intuitionistic logics, with applications in functional programming and domain theory, where a cartesian closed category is taken as a non-syntactic description of a lambda calculus. At the very least, category theoretic language clarifies what exactly these related areas have in common (in some abstract sense).

Category theory has been applied in other fields as well. For example, John Baez has shown a link between Feynman diagrams in physics and monoidal categories.[7] Another application of category theory, more specifically: topos theory, has been made in mathematical music theory, see for example the book The Topos of Music, Geometric Logic of Concepts, Theory, and Performance by Guerino Mazzola.

More recent efforts to introduce undergraduates to categories as a foundation for mathematics include those of William Lawvere and Rosebrugh (2003) and Lawvere and Stephen Schanuel (1997) and Mirroslav Yotov (2012).

See also

Notes

- Some authors compose in the opposite order, writing fg or f ∘ g for g ∘ f. Computer scientists using category theory very commonly write f ; g for g ∘ f

- Note that a morphism that is both epic and monic is not necessarily an isomorphism! An elementary counterexample: in the category consisting of two objects A and B, the identity morphisms, and a single morphism f from A to B, f is both epic and monic but is not an isomorphism.

References

Citations

- Awodey, Steve (2010) [2006]. Category Theory. Oxford Logic Guides. 49 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923718-0.

- Geroch, Robert (1985). Mathematical physics ([Repr.] ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 7. ISBN 978-0-226-28862-8.

Note that theorem 3 is actually easier for categories in general than it is for the special case of sets. This phenomenon is by no means rare.

- Coecke, B., ed. (2011). New Structures for Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics. 831. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783642128202.

- Rosen, Robert (1958). "The representation of biological systems from the standpoint of the theory of categories" (PDF). Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 20 (4): 317–341. doi:10.1007/BF02477890.

- Mac Lane 1998, p. 18: "As Eilenberg-Mac Lane first observed, 'category' has been defined in order to be able to define 'functor' and 'functor' has been defined in order to be able to define 'natural transformation'."

- Eilenberg, Samuel; MacLane, Saunders (1945). "General theory of natural equivalences". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 58: 247. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1945-0013131-6. ISSN 0002-9947.

- Baez, J.C.; Stay, M. (2009). "Physics, topology, logic and computation: A Rosetta stone". arXiv:0903.0340 [quant-ph].

Sources

- Adámek, Jiří; Herrlich, Horst; Strecker, George E. (2004). Abstract and Concrete Categories. Heldermann Verlag Berlin.

- Barr, Michael; Wells, Charles (2012) [1995], Category Theory for Computing Science, Reprints in Theory and Applications of Categories, 22 (3rd ed.).

- Barr, Michael; Wells, Charles (2005), Toposes, Triples and Theories, Reprints in Theory and Applications of Categories, 12, MR 2178101.

- Borceux, Francis (1994). Handbook of categorical algebra. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 9780521441780.

- Freyd, Peter J. (2003) [1964]. Abelian Categories. Reprints in Theory and Applications of Categories. 3.

- Freyd, Peter J.; Scedrov, Andre (1990). Categories, allegories. North Holland Mathematical Library. 39. North Holland. ISBN 978-0-08-088701-2.

- Goldblatt, Robert (2006) [1979]. Topoi: The Categorial Analysis of Logic. Studies in logic and the foundations of mathematics. 94. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-45026-1.

- Herrlich, Horst; Strecker, George E. (2007). Category Theory (3rd ed.). Heldermann Verlag Berlin. ISBN 978-3-88538-001-6..

- Kashiwara, Masaki; Schapira, Pierre (2006). Categories and Sheaves. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften. 332. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-27949-5.

- Lawvere, F. William; Rosebrugh, Robert (2003). Sets for Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01060-3.

- Lawvere, F. W.; Schanuel, Stephen Hoel (2009) [1997]. Conceptual Mathematics: A First Introduction to Categories (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89485-2.

- Leinster, Tom (2004). Higher Operads, Higher Categories. Higher Operads. London Math. Society Lecture Note Series. 298. Cambridge University Press. p. 448. Bibcode:2004hohc.book.....L. ISBN 978-0-521-53215-0. Archived from the original on 2003-10-25. Retrieved 2006-04-03.

- Leinster, Tom (2014). Basic Category Theory. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. 143. Cambridge University Press. arXiv:1612.09375. ISBN 9781107044241.

- Lurie, Jacob (2009). Higher Topos Theory. Annals of Mathematics Studies. 170. Princeton University Press. arXiv:math.CT/0608040. ISBN 978-0-691-14049-0. MR 2522659.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998). Categories for the Working Mathematician. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 5 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-98403-2. MR 1712872.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mac Lane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1999) [1967]. Algebra (2nd ed.). Chelsea. ISBN 978-0-8218-1646-2.

- Martini, A.; Ehrig, H.; Nunes, D. (1996). "Elements of basic category theory". Technical Report. 96 (5).

- May, Peter (1999). A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51183-2.

- Guerino, Mazzola (2002). The Topos of Music, Geometric Logic of Concepts, Theory, and Performance. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-7643-5731-3.

- Pedicchio, Maria Cristina; Tholen, Walter, eds. (2004). Categorical foundations. Special topics in order, topology, algebra, and sheaf theory. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications. 97. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83414-8. Zbl 1034.18001.

- Pierce, Benjamin C. (1991). Basic Category Theory for Computer Scientists. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66071-6.

- Schalk, A.; Simmons, H. (2005). An introduction to Category Theory in four easy movements (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2007-12-03. Notes for a course offered as part of the MSc. in Mathematical Logic, Manchester University.

- Simpson, Carlos (2010). Homotopy theory of higher categories. arXiv:1001.4071. Bibcode:2010arXiv1001.4071S., draft of a book.

- Taylor, Paul (1999). Practical Foundations of Mathematics. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. 59. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63107-5.

- Turi, Daniele (1996–2001). "Category Theory Lecture Notes" (PDF). Retrieved 11 December 2009. Based on Mac Lane 1998.

Further reading

- Marquis, Jean-Pierre (2008). From a Geometrical Point of View: A Study of the History and Philosophy of Category Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-9384-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category theory. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Category theory |

- Theory and Application of Categories, an electronic journal of category theory, full text, free, since 1995.

- nLab, a wiki project on mathematics, physics and philosophy with emphasis on the n-categorical point of view.

- The n-Category Café, essentially a colloquium on topics in category theory.

- Category Theory, a web page of links to lecture notes and freely available books on category theory.

- Hillman, Chris, A Categorical Primer, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.24.3264, a formal introduction to category theory.

- Adamek, J.; Herrlich, H.; Stecker, G. "Abstract and Concrete Categories-The Joy of Cats" (PDF).

- Category Theory entry by Jean-Pierre Marquis in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, with an extensive bibliography.

- List of academic conferences on category theory

- Baez, John (1996). "The Tale of n-categories". — An informal introduction to higher order categories.

- WildCats is a category theory package for Mathematica. Manipulation and visualization of objects, morphisms, categories, functors, natural transformations, universal properties.

- The catsters's channel on YouTube, a channel about category theory.

- Category theory at PlanetMath.org..

- Video archive of recorded talks relevant to categories, logic and the foundations of physics.

- Interactive Web page which generates examples of categorical constructions in the category of finite sets.

- Category Theory for the Sciences, an instruction on category theory as a tool throughout the sciences.

- Category Theory for Programmers A book in blog form explaining category theory for computer programmers.

- Introduction to category theory.