Algebraic topology

Algebraic topology is a branch of mathematics that uses tools from abstract algebra to study topological spaces. The basic goal is to find algebraic invariants that classify topological spaces up to homeomorphism, though usually most classify up to homotopy equivalence.

Although algebraic topology primarily uses algebra to study topological problems, using topology to solve algebraic problems is sometimes also possible. Algebraic topology, for example, allows for a convenient proof that any subgroup of a free group is again a free group.

Main branches of algebraic topology

Below are some of the main areas studied in algebraic topology:

Homotopy groups

In mathematics, homotopy groups are used in algebraic topology to classify topological spaces. The first and simplest homotopy group is the fundamental group, which records information about loops in a space. Intuitively, homotopy groups record information about the basic shape, or holes, of a topological space.

Homology

In algebraic topology and abstract algebra, homology (in part from Greek ὁμός homos "identical") is a certain general procedure to associate a sequence of abelian groups or modules with a given mathematical object such as a topological space or a group.[1]

Cohomology

In homology theory and algebraic topology, cohomology is a general term for a sequence of abelian groups defined from a co-chain complex. That is, cohomology is defined as the abstract study of cochains, cocycles, and coboundaries. Cohomology can be viewed as a method of assigning algebraic invariants to a topological space that has a more refined algebraic structure than does homology. Cohomology arises from the algebraic dualization of the construction of homology. In less abstract language, cochains in the fundamental sense should assign 'quantities' to the chains of homology theory.

Manifolds

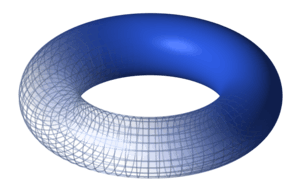

A manifold is a topological space that near each point resembles Euclidean space. Examples include the plane, the sphere, and the torus, which can all be realized in three dimensions, but also the Klein bottle and real projective plane which cannot be realized in three dimensions, but can be realized in four dimensions. Typically, results in algebraic topology focus on global, non-differentiable aspects of manifolds; for example Poincaré duality.

Knot theory

Knot theory is the study of mathematical knots. While inspired by knots that appear in daily life in shoelaces and rope, a mathematician's knot differs in that the ends are joined together so that it cannot be undone. In precise mathematical language, a knot is an embedding of a circle in 3-dimensional Euclidean space, . Two mathematical knots are equivalent if one can be transformed into the other via a deformation of upon itself (known as an ambient isotopy); these transformations correspond to manipulations of a knotted string that do not involve cutting the string or passing the string through itself.

Complexes

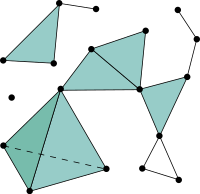

A simplicial complex is a topological space of a certain kind, constructed by "gluing together" points, line segments, triangles, and their n-dimensional counterparts (see illustration). Simplicial complexes should not be confused with the more abstract notion of a simplicial set appearing in modern simplicial homotopy theory. The purely combinatorial counterpart to a simplicial complex is an abstract simplicial complex.

A CW complex is a type of topological space introduced by J. H. C. Whitehead to meet the needs of homotopy theory. This class of spaces is broader and has some better categorical properties than simplicial complexes, but still retains a combinatorial nature that allows for computation (often with a much smaller complex).

Method of algebraic invariants

An older name for the subject was combinatorial topology, implying an emphasis on how a space X was constructed from simpler ones[2] (the modern standard tool for such construction is the CW complex). In the 1920s and 1930s, there was growing emphasis on investigating topological spaces by finding correspondences from them to algebraic groups, which led to the change of name to algebraic topology.[3] The combinatorial topology name is still sometimes used to emphasize an algorithmic approach based on decomposition of spaces.[4]

In the algebraic approach, one finds a correspondence between spaces and groups that respects the relation of homeomorphism (or more general homotopy) of spaces. This allows one to recast statements about topological spaces into statements about groups, which have a great deal of manageable structure, often making these statement easier to prove. Two major ways in which this can be done are through fundamental groups, or more generally homotopy theory, and through homology and cohomology groups. The fundamental groups give us basic information about the structure of a topological space, but they are often nonabelian and can be difficult to work with. The fundamental group of a (finite) simplicial complex does have a finite presentation.

Homology and cohomology groups, on the other hand, are abelian and in many important cases finitely generated. Finitely generated abelian groups are completely classified and are particularly easy to work with.

Setting in category theory

In general, all constructions of algebraic topology are functorial; the notions of category, functor and natural transformation originated here. Fundamental groups and homology and cohomology groups are not only invariants of the underlying topological space, in the sense that two topological spaces which are homeomorphic have the same associated groups, but their associated morphisms also correspond — a continuous mapping of spaces induces a group homomorphism on the associated groups, and these homomorphisms can be used to show non-existence (or, much more deeply, existence) of mappings.

One of the first mathematicians to work with different types of cohomology was Georges de Rham. One can use the differential structure of smooth manifolds via de Rham cohomology, or Čech or sheaf cohomology to investigate the solvability of differential equations defined on the manifold in question. De Rham showed that all of these approaches were interrelated and that, for a closed, oriented manifold, the Betti numbers derived through simplicial homology were the same Betti numbers as those derived through de Rham cohomology. This was extended in the 1950s, when Samuel Eilenberg and Norman Steenrod generalized this approach. They defined homology and cohomology as functors equipped with natural transformations subject to certain axioms (e.g., a weak equivalence of spaces passes to an isomorphism of homology groups), verified that all existing (co)homology theories satisfied these axioms, and then proved that such an axiomatization uniquely characterized the theory.

Applications of algebraic topology

Classic applications of algebraic topology include:

- The Brouwer fixed point theorem: every continuous map from the unit n-disk to itself has a fixed point.

- The free rank of the n-th homology group of a simplicial complex is the n-th Betti number, which allows one to calculate the Euler–Poincaré characteristic.

- One can use the differential structure of smooth manifolds via de Rham cohomology, or Čech or sheaf cohomology to investigate the solvability of differential equations defined on the manifold in question.

- A manifold is orientable when the top-dimensional integral homology group is the integers, and is non-orientable when it is 0.

- The n-sphere admits a nowhere-vanishing continuous unit vector field if and only if n is odd. (For , this is sometimes called the "hairy ball theorem".)

- The Borsuk–Ulam theorem: any continuous map from the n-sphere to Euclidean n-space identifies at least one pair of antipodal points.

- Any subgroup of a free group is free. This result is quite interesting, because the statement is purely algebraic yet the simplest known proof is topological. Namely, any free group G may be realized as the fundamental group of a graph X. The main theorem on covering spaces tells us that every subgroup H of G is the fundamental group of some covering space Y of X; but every such Y is again a graph. Therefore, its fundamental group H is free. On the other hand, this type of application is also handled more simply by the use of covering morphisms of groupoids, and that technique has yielded subgroup theorems not yet proved by methods of algebraic topology; see Higgins (1971).

- Topological combinatorics.

Notable algebraic topologists

- Frank Adams

- Michael Atiyah

- Enrico Betti

- Armand Borel

- Karol Borsuk

- Luitzen Egbertus Jan Brouwer

- William Browder

- Ronald Brown

- Henri Cartan

- Albrecht Dold

- Charles Ehresmann

- Samuel Eilenberg

- Hans Freudenthal

- Peter Freyd

- Pierre Gabriel

- Alexander Grothendieck

- Allen Hatcher

- Friedrich Hirzebruch

- Heinz Hopf

- Michael J. Hopkins

- Witold Hurewicz

- Egbert van Kampen

- Daniel Kan

- Hermann Künneth

- Ruth Lawrence

- Solomon Lefschetz

- Jean Leray

- Saunders Mac Lane

- Mark Mahowald

- J. Peter May

- Barry Mazur

- John Milnor

- John Coleman Moore

- Jack Morava

- Emmy Noether

- Sergei Novikov

- Grigori Perelman

- Lev Pontryagin

- Nicolae Popescu

- Mikhail Postnikov

- Daniel Quillen

- Jean-Pierre Serre

- Stephen Smale

- Edwin Spanier

- Norman Steenrod

- Dennis Sullivan

- René Thom

- Hiroshi Toda

- Leopold Vietoris

- Hassler Whitney

- J. H. C. Whitehead

- Gordon Thomas Whyburn

Important theorems in algebraic topology

- Borsuk–Ulam theorem

- Brouwer fixed point theorem

- Cellular approximation theorem

- Eilenberg–Zilber theorem

- Freudenthal suspension theorem

- Hurewicz theorem

- Künneth theorem

- Poincaré duality theorem

- Seifert–van Kampen theorem

- Universal coefficient theorem

- Whitehead's theorem

See also

Notes

- Fraleigh (1976, p. 163)

- Fréchet, Maurice; Fan, Ky (2012), Invitation to Combinatorial Topology, Courier Dover Publications, p. 101, ISBN 9780486147888.

- Henle, Michael (1994), A Combinatorial Introduction to Topology, Courier Dover Publications, p. 221, ISBN 9780486679662.

- Spreer, Jonathan (2011), Blowups, slicings and permutation groups in combinatorial topology, Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH, p. 23, ISBN 9783832529833.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Algebraic topology. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Algebraic topology |

- Allegretti, Dylan G. L. (2008), Simplicial Sets and van Kampen's Theorem (Discusses generalized versions of van Kampen's theorem applied to topological spaces and simplicial sets).

- Bredon, Glen E. (1993), Topology and Geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 139, Springer, ISBN 0-387-97926-3.

- Brown, R. (2007), Higher dimensional group theory (Gives a broad view of higher-dimensional van Kampen theorems involving multiple groupoids).

- Brown, R.; Razak, A. (1984), "A van Kampen theorem for unions of non-connected spaces", Archiv. Math., 42: 85–88, doi:10.1007/BF01198133. "Gives a general theorem on the fundamental groupoid with a set of base points of a space which is the union of open sets."

- Brown, R.; Hardie, K.; Kamps, H.; Porter, T. (2002), "The homotopy double groupoid of a Hausdorff space", Theory Appl. Categories, 10 (2): 71–93.

- Brown, R.; Higgins, P.J. (1978), "On the connection between the second relative homotopy groups of some related spaces", Proc. London Math. Soc., S3-36 (2): 193–212, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-36.2.193. "The first 2-dimensional version of van Kampen's theorem."

- Brown, Ronald; Higgins, Philip J.; Sivera, Rafael (2011), Nonabelian Algebraic Topology: Filtered Spaces, Crossed Complexes, Cubical Homotopy Groupoids, European Mathematical Society Tracts in Mathematics, 15, European Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-3-03719-083-8, archived from the original on 2009-06-04 This provides a homotopy theoretic approach to basic algebraic topology, without needing a basis in singular homology, or the method of simplicial approximation. It contains a lot of material on crossed modules.

- Fraleigh, John B. (1976), A First Course In Abstract Algebra (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-01984-1

- Greenberg, Marvin J.; Harper, John R. (1981), Algebraic Topology: A First Course, Revised edition, Mathematics Lecture Note Series, Westview/Perseus, ISBN 9780805335576. A functorial, algebraic approach originally by Greenberg with geometric flavoring added by Harper.

- Hatcher, Allen (2002), Algebraic Topology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79540-0. A modern, geometrically flavoured introduction to algebraic topology.

- Higgins, Philip J. (1971), Notes on categories and groupoids, Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 9780442034061

- Maunder, C. R. F. (1970), Algebraic Topology, London: Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 0-486-69131-4.

- tom Dieck, Tammo (2008), Algebraic Topology, EMS Textbooks in Mathematics, European Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-3-03719-048-7

- van Kampen, Egbert (1933), "On the connection between the fundamental groups of some related spaces", American Journal of Mathematics, 55 (1): 261–7, JSTOR 51000091

- "Van Kampen's theorem". PlanetMath.

- "Van Kampen's theorem result". PlanetMath.

Further reading

- Hatcher, Allen (2002). Algebraic topology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79160-X. and ISBN 0-521-79540-0.

- "Algebraic topology", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- May JP (1999). A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology (PDF). University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 2008-09-27. Section 2.7 provides a category-theoretic presentation of the theorem as a colimit in the category of groupoids.