Calexico, California

Calexico (/kəˈlɛksɪkoʊ/) is a city in southern Imperial County, California. Situated on the Mexico–United States border, it is linked economically with the much larger city of Mexicali, the capital of the Mexican state of Baja California.[7] It is about 122 miles (196 km) east of San Diego and 62 miles (100 km) west of Yuma, Arizona. Calexico, along with six other incorporated Imperial County cities, forms part of the larger populated area known as the Imperial Valley.

Calexico, California | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Calexico | |

Top: City Hall; Bottom: Hotel de Anza | |

Seal | |

| Nicknames: The International Gateway City Where California and Mexico Meet | |

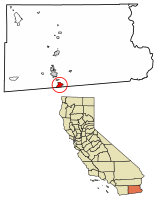

Location of Calexico in Imperial County, California | |

Calexico, California Location in the contiguous United States | |

| Coordinates: 32°40′44″N 115°29′56″W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | April 16, 1908[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager government[3] |

| • Mayor | Lewis Pacheco[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.62 sq mi (22.32 km2) |

| • Land | 8.62 sq mi (22.32 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 3 ft (0.9 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 38,572 |

| • Estimate (2019)[6] | 39,825 |

| • Density | 4,620.61/sq mi (1,783.93/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 92231–92232 |

| Area code(s) | 760/442 |

| FIPS code | 06-09710 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652680, 2409958 |

| Website | www |

First explored in the 18th century, Calexico began as a small tent community which was ultimately incorporated in 1908.

Etymology

The name of the city is a portmanteau of California and Mexico. The originally proposed names were Santo Tomas or Thomasville. Mexicali is a similarly named city directly across the international border from Calexico, its name being a portmanteau of the words "Mexico" and "California".

History

The expedition of Spanish explorer Juan Bautista de Anza traveled through the area some time between 1775 and 1776, during Spanish rule. The trail through Calexico was designated as a historical route by the State of California.

Founding

Calexico began as a tent city of the Imperial Land Company; it was founded in 1899, and incorporated in 1908. The Imperial Land Company converted desert land into a fertile setting for year-round agriculture. The first post office in Calexico opened in 1902.[8]

2010 earthquake

On April 4, 2010, the El Mayor earthquake caused moderate to heavy damage throughout Calexico and across the border in Mexicali. Measuring 7.2 Mw, the quake was centered about 40 miles (64 km) south of the U.S.–Mexico border near Mexicali.[9] A state of emergency was declared and officials cordoned off First and Second streets between Paulin and Heber Avenues. Glass and debris littered the streets of downtown Calexico and two buildings partially collapsed. The Calexico water treatment plant sustained severe damage.[10]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, at the 2010 census, the city had a total area of 6.2 square miles (16 km2), all land. Calexico is located 230 miles (370 km) southeast of Los Angeles, 125 miles (201 km) east of San Diego, 260 miles (420 km) west of Phoenix, and adjacent to Mexicali, Baja California, Mexico.

Calexico's location provides easy overnight trucking access to all those transportation hubs plus the ports of Long Beach, California, and Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico.

Calexico is served by State Routes 98, 7 and 111, with direct connection to Interstate 8 (5 miles north) and State Route 86. There are eighteen regular and irregular common carriers for intrastate and interstate truck service to Calexico.

Rail service is provided by Union Pacific Railroad, and connects with the main line to Portland, Oregon; Rock Island, Illinois; Tucumcari, New Mexico; St. Louis, Missouri; and New Orleans, Louisiana.

Within city limits is Calexico International Airport, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection check-point for private passenger and air-cargo flights entering the U.S. from Mexico. Private charter services are also available there.

General aviation facilities and scheduled passenger and air-cargo service to San Diego International Airport, Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, and other points are available at Imperial County Airport (Boley Field), located 17 miles (27 km) north.

Climate

Calexico has a subtropical hot-desert climate (BWh), according to the Köppen climate classification system. In December 1932, the city experienced a rare snowfall. Rainfall usually occurs in the winter months of December, January and February. Although summer is extremely dry in Calexico, there are occasional thunderstorms. In 2008, during the months of July and August there were several heavy thunderstorms that let down large amounts of rain and hail. Summer rainfall in the city is infrequent. During winter time, Calexico is sometimes affected by winter rain showers.

The summer temperatures in Calexico are very hot, with most of those days having temperatures at or above 100 °F (38 °C). However, the hot desert climate seen in Calexico is actually not unusual for similar parallels, seen in Baghdad, Iraq for example.

The area has a large amount of sunshine year round due to its stable descending air and high pressure.

| Climate data for Calexico, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

93 (34) |

101 (38) |

109 (43) |

116 (47) |

121 (49) |

122 (50) |

120 (49) |

120 (49) |

112 (44) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

122 (50) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

75 (24) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

94 (34) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

91 (33) |

78 (26) |

70 (21) |

88 (31) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

45 (7) |

49 (9) |

54 (12) |

61 (16) |

68 (20) |

76 (24) |

77 (25) |

71 (22) |

59 (15) |

47 (8) |

41 (5) |

57 (14) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

24 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

34 (1) |

36 (2) |

47 (8) |

52 (11) |

54 (12) |

48 (9) |

33 (1) |

24 (−4) |

22 (−6) |

18 (−8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.51 (13) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.35 (8.9) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.43 (11) |

2.96 (75.21) |

| Source: [11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 797 | — | |

| 1920 | 6,223 | 680.8% | |

| 1930 | 6,299 | 1.2% | |

| 1940 | 5,415 | −14.0% | |

| 1950 | 6,433 | 18.8% | |

| 1960 | 7,992 | 24.2% | |

| 1970 | 10,625 | 32.9% | |

| 1980 | 14,412 | 35.6% | |

| 1990 | 18,633 | 29.3% | |

| 2000 | 27,109 | 45.5% | |

| 2010 | 38,572 | 42.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 39,825 | [6] | 3.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

The 2010 United States Census reported that Calexico had a population of 38,572. The population density was 4,596.7 people per square mile (1,774.8/km2). The racial makeup of Calexico was 23,150 (60.0%) White, 134 (0.3%) African American, 204 (0.5%) Native American, 504 (1.3%) Asian, 21 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 12,920 (33.5%) from other races, and 1,639 (4.2%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 37,354 persons (96.8%).

The Census reported that 38,472 people (99.7% of the population) lived in households, 100 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 0 (0%) were institutionalized.

There were 10,116 households, out of which 5,759 (56.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 5,767 (57.0%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 2,319 (22.9%) had a female householder with no husband present, 595 (5.9%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 316 (3.1%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 61 (0.6%) same-sex married couples or partnerships, while 1,200 households (11.9%) were made up of individuals, and 675 (6.7%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.80. There were 8,681 families (85.8% of all households); the average family size was 4.09.

The population was spread out, with 12,011 people (31.1%) under the age of 18, 4,262 people (11.0%) aged 18 to 24, 9,332 people (24.2%) aged 25 to 44, 8,559 people (22.2%) aged 45 to 64, and 4,408 people (11.4%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.2 males.

There were 10,651 housing units at an average density of 1,269.3 per square mile (490.1/km2), of which 10,116 were occupied, of which 5,430 (53.7%) were owner-occupied, and 4,686 (46.3%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.6%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.1%. 22,155 people (57.4% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 16,317 people (42.3%) lived in rental housing units.[13]

Government

The City of Calexico operates under a City Council/City Manager form of government. The City Council consists of five Council Members, elected to overlapping four-year term. The Mayor and Mayor Pro-Tem are chosen from among the five council members and rotate on an annual basis.

The Mayor presides at council meetings, where all official policies and laws of the City are enacted. The members of the Calexico City Council set policy and appoint commissions and committees that study the present and future needs of Calexico.

The other two elected officials in the City of Calexico are the City Clerk and City Treasurer. Each of them is elected directly by the voters and serves a four-year term.

The Calexico branch of the Imperial County Superior Court system was officially renamed on Saturday, December 19, 1992 in honor of Legaspi family members Henry, Victor and Luis Legaspi as the Legaspi Municipal Court Complex.[14]

Politics

In the state legislature, Calexico is in the 40th Senate District, represented by Democrat Ben Hueso,[15] and the 56th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Eduardo Garcia.[16]

Federally, Calexico is in California's 51st congressional district, represented by Democrat Juan Vargas.[17]

The current mayor is Lewis Pacheco, and the mayor pro tem is Jesus Eduardo Escobar. The other council members are Bill Hodge, Maritza Hurtado, and Armando G. Real.[3]

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016[18] | 86.30% 10,226 | 9.78% 1,159 | 3.92% 465 |

| 2012[19] | 85.73% 7,150 | 13.03% 1,087 | 1.24% 103 |

| 2008[20] | 82.68% 6,689 | 15.75% 1,274 | 1.57% 127 |

| 2004[21] | 73.38% 3,471 | 25.16% 1,190 | 1.46% 69 |

| 2000[22] | 75.25% 3,557 | 21.94% 1,037 | 2.81% 133 |

| 1996[23] | 84.91% 2,780 | 11.91% 390 | 3.18% 104 |

| 1992[24] | 62.82% 1,803 | 28.36% 814 | 8.82% 253 |

| 1988[25] | 71.54% 1,629 | 27.93% 636 | 0.53% 12 |

| 1984[26] | 60.53% 1,161 | 38.32% 735 | 1.15% 22 |

| 1980[27] | 64.26% 1,208 | 27.71% 521 | 8.03% 151 |

| 1976[28] | 66.75% 1,267 | 30.98% 588 | 2.27% 43 |

| 1972[29] | 57.45% 1,126 | 40.36% 791 | 2.19% 43 |

| 1968[30] | 56.04% 947 | 39.35% 665 | 4.62% 78 |

| 1964[31] | 67.35% 1,215 | 32.65% 589 |

In recent years, Calexico has overwhelmingly supported Democratic Party candidates for president. In seven of the last eight presidential elections, the Democrat has received over 70% of the vote.

Education

Colleges and universities

Post-secondary education is available at the Imperial Valley Campus of San Diego State University, and at Imperial Valley College (11 miles (18 km) to the north). In addition, there are more than 20 local agencies and programs providing vocational training which can be tailored to the specific needs of potential employers.

Public schools

The Calexico Unified School District serves city residents.

Elementary

- Grades K–6

- Kennedy Gardens Elementary – Home of the Eagles

- Allen and Helen Mains Elementary – Home of the Trojans

- Rockwood Elementary – Home of the Rockets

- Blanche Charles Elementary – Home of the Dolphins

- Jefferson Elementary – Home of the Tigers

- Dool Elementary – Home of the Cougars

- Cesar Chavez Elementary – Home of the Lobos

Junior High Schools

Grades 7–8

- Willam Moreno Jr. High – Home of the Aztecs

- Enrique Camarena Junior High School – Home of the Firebirds

High Schools

- Grades 9–12

- Calexico High School 9th Campus - Home of the Bulldogs

- Calexico High School – Home of the Bulldogs

- Aurora High School – Home of the Eagles

Public charter school (Independent Study)

RAI Online Charter School—raicharter.net (K–12, tuition-free)

Adult education schools

- Robert F. Morales Adult Education Center

- Independent Studies Office

Private schools

Calexico Mission School, a Seventh-day Adventist Academy operated by the Southeastern California Conference[32] in Riverside, CA provides private religious education in Calexico from kindergarten through twelfth grade.

Our Lady of Guadalupe Academy (Home to the Bees), and Vincent Memorial Catholic High School (Home to the Scots), Roman Catholic schools operated by the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego, are also in Calexico.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Calexico is served by the privately owned Calexico Transit, LA Shuttle and Numero Uno Shuttle and the publicly owned Imperial Valley Transit for local transit.[33] Calexico is also served by Greyhound Lines.

Freight rail service is provided by Union Pacific Railroad's Calexico Subdivision.

Community

Calexico generally identifies as part of the larger Imperial Valley region, which includes the El Centro metropolitan area, as do the rest of the cities in the county.

Notable sites

- Hotel De Anza (Hotel establishment notable for its history and having served celebrities and public figures)

- Calexico Carnegie Library (Carnegie library built in 1918 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005)

- US Inspection Station – Calexico (Historically used as the original port of entry during the early 20th century – was closed and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1992)

- Camp Salvation (Refugee camp established in 1849 by Lieut. Cave for emigrants coming from the Southern Emigrant Trail during the California Gold Rush – was registered as a California Historical Landmarks site in 1965.)

- Camp John H. Beacom – a semipermanent camp named after Colonel John H. Beacom (6th infantry) garrisoned in Calexico during World War I for patrolling duties. The site was abandoned in 1920 according to cavalry journals.[34]

- Camp Calexico was another post used for patrolling duties by Colonel W. G. Schreibe and his infantry in 1914[35]

- Mount Signal Solar (One of the largest PV solar farms in the world)

Red Ribbon Week:

Red Ribbon Week, a national observance dedicated to spreading awareness about the prevention of drugs and violence (especially in schools) originated within the city of Calexico during the mid to late 1980s as a tribute to DEA officer Enrique "Kiki" Camarena. Red Ribbon Week campaigns were pushed forward by Nancy Reagan.

Media

The city media includes national public television stations, county-wide radio stations (some of which feature nation-wide or California state-wide programing), county-wide print publications such as Imperial Valley Press as well as a few locally managed general interest publications.

In popular culture

Film and television

- 1983 film Curtis Hanson's Losin' It starring Tom Cruise was filmed in Calexico

- 1997 film The Game starring Michael Douglas; some scenes in Mexicali were shot through the chain link fence (camera and crew in Calexico) between the US and Mexico

- The film Sky High (1922 film) written and directed by Lynn Reynolds revolves around Calexico

- 1949 film The Walking Hills directed by John Sturges takes place in Mexicali and Calexico

- The town is featured in the series Knight Rider during the episode "The Mouth of The Snake". Michael Knight travels there to meet with the widow of a murdered federal lawyer.

- In the film, Bordertown (2006 film) starring Jennifer Lopez, Antonio Banderas and Martin Sheen one scene was shot in the Calexico port of entry.

- In the episode of Defiance, "The Serpent's Egg", the lawkeeper travels to Calexico.

- On ABC's hit show Modern Family, the main characters travel to Calexico in search of a child to adopt where the city's people and environment are exaggerated with stereotypes for comedic effect.

- In an episode of California's Gold, the host visits Calexico.

- The town in Seth MacFarlane's Bordertown, Mexifornia is a parody of Calexico

- The town is mentioned in first episode of Narcos: Mexico (which was originally intended to be the fourth season of the Netflix original series Narcos). The TV series Narcos: Mexico portrays Enrique Camarena, DEA agent and Calexico High School alumnus, amongst its main characters.

- In season 19; episode 2 of BBC's Top Gear (2002 TV series), starring members of the show race in sports cars from Las Vegas, Nevada to Calexico

- The 2007 independent film Descension was filmed in Calexico

Music

- The band Calexico is named after the town

- Rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers sing about Calexico in their song "Encore" from their 2016 album, The Getaway

Literature

- A narcotics officer in Michael Connelly's The Black Ice is named after the town

- Johnny Shaw's A Jimmy Veeder Fiasco novel series takes place in various parts of Imperial County including Calexico[36]

- In the novel Against All Enemies by Tom Clancy one scene is set on the Calexico/Mexicali border

- Journalist and film maker Peter Laufer writes about the city in his books ¡Calexico!:True Lives of the Borderlands and Calexico: Hope and Hysteria in the California Borderlands (co-written with Markos Kounalakis)[37]

- The book Memories of Calexico: Curse or Blessing? by Antonio A. Velasquez compiles several anecdotes about Calexico[38]

- Jim Davidson's novel Postmarked Calexico makes references to the city[39]

Notable people

- Enrique Camarena (DEA agent)[40]

- Enrique Castillo (Actor)[41]

- Emilio Delgado (Actor)[42]

- Bob Huff (California senator)[43]

- Ruben Niebla (Major League Baseball player)[44]

- Danny Villanueva, (NFL placekicker and punter)[45]

- Eugenio Elorduy Walther (Politician)[46]

- Bob Wilson (U.S. Congressman)[47]

- Allen Strange (Composer)

- Takashi Kijima (Photographer)

- William Kesling (Architect)

- Johnny Shaw (Author)[48]

- Primo Villanueva (Football player)

- Mariano-Florentino Cuellar (Justice)

- Henry Lozano (Politician)

- Ben Hulse (Politician)

- Jeff Cravath (Football player and coach)

- Bill Binder (restaurateur and owner of Philippe's in Downtown Los Angeles)

Notable visitors

- Melchor Diaz and Juan Bautista De Anza explored the region by cavalry in the 1770s.

- Don Sebastian (Professional wrestler and fourth husband of actress Lynne roberts) First came to the United States arriving through Calexico.

- Lt. James Harbord (US Army Officer) stationed at Camp John H. Beacom (Present day Calexico International airport) in 1914.

- Richard Overton Hunziker (Decorated WWI fighter pilot/US Airforce major general during the Cold war. Visited Calexico with his wife on his own plane in 1971.

- Douglass T. Greene (US Army major general; WWII) Transferred to the 21st infantry division at Camp John H. Beacom (March 16 – Apr 22 1917)

- Paul L. Williams (US Army Air Forces/US Air Force general; WWI & WWII) Served patrol duty with 9th Aero Squadron in November 1919

- American screenwriter, Nathanael West stayed in Calexico's Hotel De Anza with his wife in 1940.

- Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor of California, visited Calexico in 2010 to address the situation resulting from the 2010 Baja earthquake.

- Calexico became a center of the national debate on border security as Vice President Mike Pence and Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen toured Calexico in 2018.[49] American President Donald Trump proposed expansion of the border wall between Mexico and the US to prevent illegal entry by foreign nationals through Mexico into the US during his presidential campaign and upon being elected.[50] Trump visited the barrier at the border with Mexico in April 2019 which was described by his office as “a newly completed section of the promised border wall.”[50] He had proposed closing the border which concerned many in Calexico since the regional economy depends on daily border crossing. Mexicans come daily to work in the agriculture fields and to shop or use other services. Likewise, people travel from Calexico into Mexico to obtain services or visit relatives.[51]

See also

- Imperial County

- Imperial Valley

- Calexico–Mexicali

References

- "Calexico". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "About the City Council". City of Calexico. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- "Mayor and City Council". City of Calexico, California. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Rivlin-Nadler, Max (April 4, 2019). "As Trump Visits Calexico, Calif., Residents Worry About Rising Border Wall Tension". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 1401. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-04-07. Retrieved 2017-08-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ivblogz.com – Stay Connected in the Imperial Valley". Archived from the original on March 27, 2010.

- "Historical Averages for Calexico, CA". Intellicast. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Calexico city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- “Calexico Chronicle” Vol. 90, No. 21, December 24, 1992.

- "Senators". State of California. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "California's 51st Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "Results" (PDF). elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov. 2016. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Results" (PDF). elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov. 2012. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Results" (PDF). elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov. 2008. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "pres_general_ssov_for_all.xls" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Results" (PDF). elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov. 2000. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Results" (PDF). elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov. 1996. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Results" (PDF). elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov. 1992. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- "Statement of vote". Sacramento, Calif. : The Secretary. September 26, 1968 – via Internet Archive.

- "Statement of vote". Sacramento, Calif. : The Secretary. September 26, 1968 – via Internet Archive.

- "Statement of vote". Sacramento, Calif. : The Secretary. September 26, 1968 – via Internet Archive.

- "Statement of vote". Sacramento, Calif. : The Secretary. September 26, 1968 – via Internet Archive.

- "Statement of vote". Sacramento, Calif. : The Secretary. September 26, 1968 – via Internet Archive.

- "California statement of vote". [Sacramento, Calif.] : Secretary of State. September 26, 1962 – via Internet Archive.

- "California statement of vote". [Sacramento, Calif.] : Secretary of State. September 26, 1962 – via Internet Archive.

- "Office of Education - Home". www.secceducation.org.

- Huitt-Zollars, Inc.; PRM Consulting, Inc. Calexico border intermodal transportation center feasibility study (PDF).

- "Historic California Posts: Camp John H. Beacom". www.militarymuseum.org.

- "Historic California Posts: Camp Calexico". www.militarymuseum.org.

- "Official Website of Johnny Shaw".

- . ISBN 0981576931. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . ASIN B07MYSGQSV. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Davidson, Jim (2010-10-29). Postmarked Calexico. Sedona, Arizona. ISBN 9780941283243. OCLC 853008514.

- "Kiki and the History of Red Ribbon Week". Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Actor Enrique Castillo To Receive Distinguished Award From Arts Council". Latin Heat Entertainment. 4 November 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "People in your neighborhood". Sesame Street Workshop. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Sen. Robert 'Bob' S. Huff's biography". Project Vote Smart. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "PressReader.com - Your favorite newspapers and magazines". www.pressreader.com. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- "Danny Villanueva, co-founder of Univision, dies at 77". Los Angeles Times. 20 June 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Dibble, Sandra (20 February 2007). "Newly sworn in acting mayor embodies this binational city". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Wilson, Robert Carlton (Bob), (1916–1999)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "BIO | Official Website of Johnny Shaw".

- Shapiro, Ari (April 5, 2019). "Calexico Mayor Lewis Pacheco Discusses Trump's Visit To California Border Town". NPR.org. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- Bierman, Noah; O'Toole, Molly; Vives, Ruben (April 5, 2019). "Trump visits Calexico a day after he retreated from threats to close the U.S.-Mexico border". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- RIVLIN-NADLER, MAX (April 4, 2019). "As Trump Visits Calexico, Calif., Residents Worry About Rising Border Wall Tension". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calexico, California. |