L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle

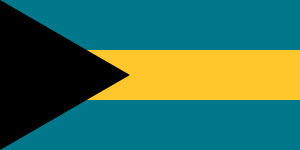

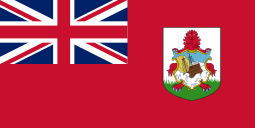

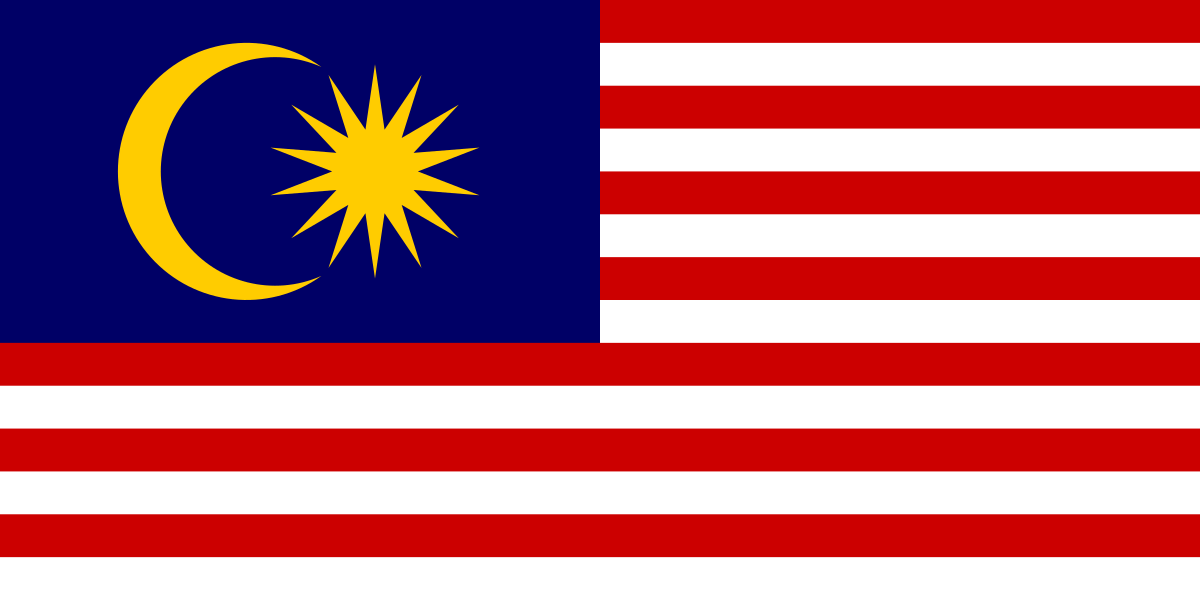

The L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle, also known as the SLR (Self-Loading Rifle), by the Canadian Army designation C1A1 (C1) or in the US as the "inch pattern" FAL,[nb 1] is a British version of the Belgian FN FAL battle rifle (Fusil Automatique Léger, "Light Automatic Rifle") produced by the Belgian armaments manufacturer Fabrique Nationale de Herstal (FN). The L1A1 was produced under licence and has seen use in the Australian Army, Canadian Army, Indian Army, Jamaica Defence Force, Malaysian Army, New Zealand Army, Rhodesian Army, Singapore Army, South African Army and the British Armed Forces.[3]

| Rifle, 7.62 mm, L1A1 (SLR) | |

|---|---|

An L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle | |

| Type | Semi-automatic rifle (L1A1/C1) Light machine gun (L2A1/C2) Assault rifle (Ishapore 1A/1C) |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1954–present |

| Used by | British Commonwealth (See Users) |

| Wars | See Conflicts |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Dieudonné Saive, Ernest Vervier |

| Designed | 1947–53 |

| Manufacturer | Royal Small Arms Factory and Birmingham Small Arms Company factories (UK),[1] Lithgow Small Arms Factory (Australia) Canadian Arsenals, Ltd. (Canada) Ordnance Factory Board (India) |

| Produced | 1954–1999 |

| Variants | L1A1/C1/C1A1 (Rifles) L2A1/C2/C2A1 (Squad automatic weapons) |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 4.337 kg (9.56 lbs) empty[2] |

| Length | 1,143 mm (45 in) |

| Barrel length | 554.4 mm (21.7 in) |

| Cartridge | 7.62×51mm NATO |

| Action | Gas-operated, tilting breechblock |

| Rate of fire | Semi-automatic (L1A1, C1A1) Fully Automatic (L2A1, C2A1) 675-750RPM |

| Muzzle velocity | 823 m/s (2,700 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 800 m (875 yds) (Effective range) |

| Feed system | 20- or 30-round detachable box magazine |

| Sights | Aperture rear sight, post front sight |

The original FAL was designed in Belgium, while the components of the "inch-pattern" FALs are manufactured to a slightly modified design using British imperial units. Many sub-assemblies are interchangeable between the two types, while components of those sub-assemblies may not be compatible. Notable incompatibilities include the magazines and the butt-stock, which attach in different ways. Most FALs also use SAE threads for barrels and assemblies. The only exceptions are early prototype FALs, and the breech threads only on Israeli and Indian FALs. All others have standard Imperial or "unified" inch-standard threads throughout.

Most Commonwealth pattern FALs are semi-automatic only. A variant named L2A1/C2A1 (C2), meant to serve as a light machine gun in a support role, is also capable of fully automatic fire. Differences from the L1A1/C1 include a heavy barrel, squared front sight (versus the "V" on the semi-automatic models), a handguard that doubles as a foldable bipod, and a larger 30-round magazine although it could also use the normal 20-round magazines. Only Canada and Australia used this variant. However, Australia, the UK and New Zealand used Bren light machine guns converted to fire the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge for use in the support role. Canadian C1s issued to naval and army personnel were also capable of fully automatic fire.

History

The L1A1 and other inch-pattern derivatives trace their lineage back to the Allied Rifle Commission of the 1950s, whose intention was to introduce a single rifle and cartridge that would serve as standard issue for all NATO countries. After briefly adopting the Rifle No. 9 Mk 1 with a 7 mm intermediate cartridge, the UK, believing that, if they adopted the Belgian FAL and the American 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge, the United States would do the same, adopted the L1A1 as a standard issue rifle in 1954. The US, however, did not adopt any variant of the FAL, opting for its own M14 rifle instead.

The L1A1 subsequently served as the UK's first-line battle rifle up to the 1980s before being replaced by the 5.56mm L85A1.

Combat service

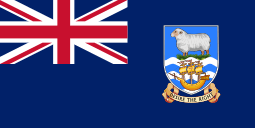

The L1A1 and variants have seen use in several conflicts, including as part of the Cold War. L1A1s have been used by the British Armed Forces in Malaysia, Northern Ireland, and in the Falklands War (in opposition to FN FAL-armed Argentine forces), the First Gulf War (where it was still on issue to some second line British Army units and RAF personnel not yet issued with the L85A1)[4], by the State of Kuwait Army during the First Gulf War,[5] by Australia and New Zealand in Vietnam,[6] by Nigerian and Biafran forces during Nigerian Civil War and by Rhodesia in the Rhodesian Bush War.

Replacement

Starting in the mid-1980s, the UK started replacing its 30-year-old L1A1 rifle with the 5.56 NATO bullpup design L85A1 assault rifle. Australia chose the Steyr AUG as a replacement in the form of the F88 Austeyr, with New Zealand following suit shortly after. Canada replaced its C1 rifle with the AR-15 variants: the C7 service rifle and C8 carbine. Australia replaced their L2A1 heavy barrel support weapons with M60's and later with an FN Minimi variant: the F89. Canada also replaced their C2 heavy barrel support weapons with an FN Minimi variant: the C9, respectively.

Production and use

Australia

The Australian Army, as a late member of the Allied Rifle Committee along with the United Kingdom and Canada adopted the committee's improved version of the FAL rifle, designated the L1A1 rifle by Australia and Great Britain, and C1 by Canada. The Australian L1A1 is also known as the "self-loading rifle" (SLR), and in fully automatic form, the "automatic rifle" (AR). The Australian L1A1 features are almost identical to the British L1A1 version of FAL; however, the Australian L1A1 differs from its British counterpart in the design of the upper receiver lightening cuts. The lightening cuts of the Australian L1A1 most closely resembles the later Canadian C1 pattern, rather than the simplified and markedly unique British L1A1 cuts. The Australian L1A1 FAL rifle was in service with Australian forces until it was superseded by the F88 Austeyr (a licence-built version of the Steyr AUG) in 1988, though some remained in service with Reserve and training units until late 1990. Some Australian Army units deployed overseas on UN peacekeeping operations in Namibia, the Western Sahara, and Cambodia still used the L1A1 SLR and the M16A1 rifle throughout the early 1990s. The British and Australian L1A1s, and Canadian C1A1 SLRs were semi-automatic only, unless battlefield conditions mandated that modifications be made.

Australia, in co-ordination with Canada, developed a heavy-barrel version of the L1A1 as a fully automatic rifle variant, designated L2A1. The Australian heavy-barrel L2A1 was also known as the "automatic rifle" (AR). The L2A1 was similar to the FN FAL 50.41/42, but with a unique combined bipod-handguard and a receiver dust-cover mounted tangent rear sight from Canada. The L2A1 was intended to serve a role as a light fully automatic rifle or quasi-squad automatic weapon (SAW). The role of the L2A1 and other heavy barrel FAL variants is essentially the same in concept as the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) or Bren, but the Bren is far better suited to the role of a fire support base for a section, being designed for the role from the start. In practice many considered the L2A1 inferior to the Bren, as the Bren had a barrel that could be changed, and so could deliver a better continuous rate of fire, and was more accurate and controllable in the role due to its greater weight and better stock configuration. For this reason, Australia and Britain used the 7.62mm-converted L4 series Bren. Most countries that adopted the FAL rejected the heavy barrel FAL, presumably because it did not perform well in the machine gun role. Countries that did embrace the heavy barrel FAL included Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Canada, and Israel.

Unique 30-round magazines were developed for the L2A1 rifles.[7] These 30-round magazines were essentially lengthened versions of the standard 20-round L1A1 magazines, perfectly straight in design. Curved 30-round magazines from the L4A1 7.62 NATO conversion of the Bren are interchangeable with the 30-round L2A1 magazines, however they reputedly gave feeding difficulties due to the additional friction from the curved design as they must be inserted "upside down" in the L2A1. The L4A1 Bren magazines were developed as a top-mounted gravity-assisted feed magazine, the opposite of what is required for the L2A1 FAL. This was sometimes sorted out by stretching magazine springs.

The Australian L1A1/L2A1 rifles were produced by the Small Arms Factory – Lithgow, with approximately 220,000 L1A1 rifles produced between 1959 and 1986. L2A1 production was approximately 10,000 rifles produced between 1962 and 1982. Lithgow exported a large number of L1A1 rifles to many countries in the region. Among the users were New Zealand, Singapore and Papua New Guinea.

During the Vietnam War, the SLR was the standard weapon issued to Australian infantrymen.[8] Many Australian soldiers preferred the larger calibre weapon over the American M16 because they felt that the SLR was more reliable and that they could trust the NATO 7.62 round to kill an enemy soldier outright. The Australians' jungle warfare tactics used in Vietnam were informed by their experience in earlier jungle conflicts (e.g., the Malayan Emergency and the Konfrontasi campaign in Borneo) and were considered far more threatening by their Viet Cong opponents than those employed by U.S. forces.[9] The Australians considered the strengths and limitations of the SLR and its heavy ammunition load to be better suited to their tactical methods.

Another product of Australian participation in the conflict in South-East Asia was the field modification of L1A1 and L2A1 rifles by the Special Air Service Regiment for better handling. Nicknamed "the Bitch", these rifles were field modified, often from heavy barrel L2A1 automatic rifles, with their barrels cut off right in front of the gas blocks, and often with the L2A1 bipods removed to install XM148 40 mm grenade launchers mounted below the barrels.[7] The XM148 40 mm grenade launchers were obtained from U.S. forces.[7] For the L1A1, the lack of fully automatic fire resulted in the unofficial conversion of the L1A1 to full-auto capability by using lower receivers from the L2A1, which works by restricting trigger movement.[10]

Australia produced a shortened version of the L1A1 designated the L1A1-F1.[11] It was intended for easier use by soldiers of smaller stature in jungle combat, as the standard L1A1 is a long, heavy weapon. The reduction in length was achieved by installing the shortest butt length (there were three available, short, standard and long), and a flash suppressor that resembled the standard version except it projected a much smaller distance beyond the end of the rifling, and had correspondingly shorter flash eliminator slots.[12] The effect was to reduce the length of the weapon by 2 1/4 inches.[12] Trials revealed that, despite no reduction in barrel length, accuracy was slightly reduced. The L1A1-F1 was provided to Papua New Guinea,[11] and a number were sold to the Royal Hong Kong Police in 1984. They were also issued to female staff cadets at the Royal Military College Duntroon and some other Australian personnel.

In 1970, a bullpup rifle known as the KAL1 general purpose infantry rifle was built at the Small Arms Factory Lithgow using parts from the L1A1 rifle. Another version of the rifle was also built in 1973.

Canada

Canada adopted the FAL in 1954, the first country in the world to actually ante up and order enough rifles for meaningful troop trials. Up to this point, FN had been making these rifles in small test lots of ones and twos, each embodying changes and improvements over its predecessor. The Canadian order for 2,000 rifles "cast the FAL in concrete" for the first time, and at FN, from 1954 to 1958 the standard model of the FAL rifle was called the FAL 'Canada'...These excellent Canadian-built rifles were the standard arms of the Canadian military from first production in 1955 until 1984.

— The FAL Rifle[13]

The Canadian Armed Forces, the Ontario Provincial Police and Royal Canadian Mounted Police operated several versions, the most common being the C1A1,[14] similar to the British L1A1 (which became more or less a Commonwealth standard), the main difference being that rotating disc rear sight graduated from 200 to 600 yards and a two-piece firing pin. Users could fold the trigger guard into the pistol grip, which allowed them to wear mitts when firing the weapon. The Canadian rifle also has a shorter receiver cover than other Commonwealth variants to allow for refilling the magazine by charging it with stripper clips. It was manufactured under license by the Canadian Arsenals Limited company.[15] Canada was the first country to use the FAL. It served as Canada's standard battle rifle from the early 1950s to 1984, when it began to be phased out in favor of the lighter Diemaco C7, a licence-built version of the M16, with a number of features borrowed from the A1, A2 and A3 variations of the AR platform assault rifle.

The Canadians also operated a fully automatic variant, the C2A1, as a section support weapon, which was very similar to the Australian L2A1. It was similar to the FN FAL 50.41/42, but with wooden attachments to the bipod legs that work as a handguard when the legs are folded. The C2A1 used a tangent rear sight attached to the receiver cover with ranges from 200 to 1000 metres. The C1 was equipped with a 20-round magazine and the C2 with a 30-round magazine, although the two were interchangeable. Variants of the initial C1 and the product improved C1A1 were also made for the Royal Canadian Navy, which were capable of automatic fire, under the designations C1D and C1A1D.[16] These weapons are identifiable by an A for "automatic", carved or stamped into the butt stock.[15] Boarding parties for domestic and international searches use the C1D.[15]

India

The Rifle 7.62 mm 1A1 which is also known as Ishapore 1A1, is a copy of the UK L1A1 self-loading rifle. It is produced at Ordnance Factory Tiruchirappalli of the Ordnance Factories Board.[17] It differs from the UK SLR in that the wooden butt-stock uses the butt-plate from the Lee–Enfield with trap[18] for oil bottle and cleaning pull-through. The 1A1 rifle has been replaced in service with the Indian Army by the INSAS 5.56 mm assault rifle.

A fully automatic version of the rifle (known as the 1C or Ishapore 1C ) is also available, meant for use in BMP-2s via firing ports.[19][20] The 1A1 is still in use by Central Armed Police Forces, some law enforcement bodies and also used during parades by the National Cadet Corps (India).

The 1A (which is also known as Ishapore 1A), is the full automatic version based on the FN FAL while the 1A1 (which is also known as Ishapore 1A1), is the semi-automatic version based on the L1A1.[21] They can be equipped with the 1A and 1A Long Blade bayonet, based on the L1A4 bayonet.[22]

Production started in 1960 after the Armament Research & Development Establishment (ARDE) evaluated several Australian, Belgian and British FAL rifles and each one was disassembled and examined.[23] ARDE researchers began to make plans to make their own rifle after negotiations with FN were unsuccessful because of royalty requirements and the clause that Belgian technicians help manage the production lines.[23] 750 rifles were made per week.[23]

FN threatened a lawsuit when they learnt of the unlicensed variant.[23] Then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was not made aware of it and after he had heard it, offered to settle FN's complaints by agreeing to purchase additional Belgian-made FALs, FALOs and MAG 60.20 GPMGs.[23]

In 2012, around 6,000 rifles were made annually in India.[24] As of September 2019, around a million rifles were made.[25]

New Zealand

The New Zealand Army used the L1A1 as its standard service rifle for just under 30 years. The Labour government of Walter Nash approved the purchase of the L1A1 as a replacement for the No. 4 Mk 1 Lee–Enfield bolt-action rifle in 1959.[26] An order for a total of 15,000 L1A1 rifles was subsequently placed with the Lithgow Small Arms Factory in Australia which had been granted a license to produce the L1A1. However the first batch of 500 rifles from this order was not actually delivered to the New Zealand Army until 1960. Thereafter deliveries continued at an increasing pace until the order for all 15,000 rifles was completed in 1965. As with Australian soldiers, the L1A1 was the preferential rifle of New Zealand Army and NZSAS troops during the Vietnam War,[26][27] over the American M16 during the Vietnam War as they used the same combat tactics as their Australian counterparts.[28] After its adoption by the Army, the Royal New Zealand Air Force and the Royal New Zealand Navy also eventually acquired it.

Unlike L1A1s in Australian service, New Zealand L1A1s later used British black plastic furniture, and some rifles even had a mixture of the two. The carrying handles were frequently cut off. The British SUIT (Sight Unit Infantry Trilux) optical sight was issued to some users in infantry units. The L2A1 heavy barrel variant was also issued as a limited standard, but was not popular due to the problems also encountered by other users of heavy barrel FAL variants. The L4A1 7.62mm conversion of the Bren was much-preferred in New Zealand service.

The New Zealand Defence Force began replacing the L1A1 with the Steyr AUG assault rifle in 1988 and were disposed through the Government Disposal Bureau in 1990.[29][30] The Steyr AUG was phased out across all three services of the New Zealand Defence Force in 2016. The Royal New Zealand Navy still uses the L1A1 for line throwing between ships.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom produced its own variant of the FN FAL incorporating the modifications developed by the Allied Rifle Committee, designating it the L1A1 Self Loading Rifle (SLR). The weapons were manufactured by the Royal Small Arms Factory Enfield, Birmingham Small Arms, Royal Ordnance Factory and ROF Fazakerley. After the production run ceased, replacement components were made by Parker Hale Limited. The SLR served the British Armed Forces from 1954 until approximately 1994, being replaced by the L85A1 from 1985 onwards.[31]

The SLR was designed using Imperial measurements and included several changes from the standard FN FAL. A significant change from the original FAL was that the L1A1 operates in semi-automatic mode only. Other changes include: the introduction of a folding cocking handle; an enclosed slotted flash suppressor; folding rear sight; sand-clearing modifications to the upper receiver, bolt and bolt carrier; folding trigger guard to allow use with Arctic mitts; strengthened butt; enlarged change lever and magazine release catch; vertical stripping catch to prevent unintended activation; deletion of the automatic hold-open device and the addition of retaining tabs at the rear of the top cover to prevent forward movement of the top cover (and resulting loss of zero) when the L2A1 SUIT was fitted. The flash suppressor is fitted with a lug which allows the fitting of an L1-series bayonet, an L1A1/A2 or L6A1 blank firing attachment or an L1A1/A2 Energa rifle grenade launcher.

Initial production rifles were fitted with walnut furniture, consisting of the pistol grip, forward handguard, carrying handle and butt.[32] The wood was treated with oil to protect against moisture, but not varnished or polished. Later production weapons were produced with synthetic furniture.[32] The material used was Maranyl, a nylon 6-6 and fiberglass composite. The Maranyl parts have a "pebbled" anti-slip texture along with a butt has a separate butt-pad, available in four lengths to allow the rifle to be fitted to individual users. There was also a special short butt designed for use with Arctic clothing or body armour, which incorporated fixing points for an Arctic chest sling system. After the introduction of the Maranyl furniture, as extra supplies became available it was retrofitted to older rifles as they underwent scheduled maintenance. However, this resulted in a mixture of wooden and Maranyl furniture within units and often on the same rifle. Wooden furniture was still in use in some Territorial Army units and in limited numbers with the RAF until at least 1989.

The SLR selector has two settings (rather than the three that most metric FALs have), safety and semi-automatic, which are marked S (safe) and R (repetition.) The magazine from the 7.62 mm L4 light machine gun will fit the SLR;[33] however, the L4 magazine was designed for gravity assisted downwards feeding, and can be unreliable with the upwards feeding system of the SLR. Commonwealth magazines were produced with a lug brazed onto the front to engage the recess in the receiver, in place of a smaller pressed dimple on the metric FAL magazine. As a consequence of this, metric FAL magazines can be used with the Commonwealth SLR, but SLR magazines will not fit the metric FAL.[34]

Despite the British, Australian and Canadian versions of the FAL being manufactured using machine tools which utilised the Imperial measurement system, they are all of the same basic dimensions. Parts incompatibilities between the original FAL and the L1A1 are due to pattern differences, not due to the different dimensions. Confusions over the differences has given rise to the terminology of "metric" and "inch" FAL rifles, which originated as a reference to the machine tools which produced them. Despite this, virtually all FAL rifles are of the same basic dimensions, true to the original Belgian FN FAL. In the US, the term "metric FAL" refers to guns of the Belgian FAL pattern, whereas "inch FAL" refers to ones produced to the Commonwealth L1A1/C1 pattern.[35][36]

SLRs could be modified at unit level to take two additional sighting systems. The first was the "Hythe sight," formally known as the "Conversion Kit, 7.62mm Rifle Sight, Trilux, L5A1" (L5A2 and L5A3 variants with different foresight inserts also existed) and intended for use in close range and in poor lighting conditions. The sight incorporated two rear sight aperture leaves and a permanently glowing tritium foresight insert for improved night visibility, which had to be replaced after a period of time due to radioactive decay. The first rear sight leaf had a 7 mm aperture which could be used alone for night shooting or the second leaf could be raised in front of it, superimposing a 2 mm aperture for day shooting.[37] The second sight was the L2A2 "Sight Unit, Infantry, Trilux" (SUIT), a 4× optical sight which mounted on a rail welded to a top cover.[33] Issued to the British Infantry, Royal Marines and RAF Regiment, the SUIT featured a prismatic offset design, which reduced the length of the sight and improved clearance around the action. Also, the SUIT helped to reduce parallax errors and heat mirage from the barrel as it heated up during firing. The aiming mark was an inverted, tapered perspex pillar ending in a point which could be illuminated by a tritium element for use in low light conditions. The inverted sight post allowed rapid target re-acquisition after the recoil of the firearm raised the muzzle. The scope was somewhat heavy, but due to its solid construction was durable and robust.[nb 2]

The SLR was officially replaced in 1985 by the bullpup design L85A1 service rifle, firing the 5.56×45mm NATO cartridge. The armed forces were re-equipped by 1994 and during this period the L1A1 rifles were gradually phased out. Most were either destroyed or sold, with some going to Sierra Leone. Several thousand were sent to the US and sold as parts kits, and others were refurbished by LuxDefTec in Luxembourg and are still on sale to the European market.[38]

Gallery

United States Marine with a British L1A1 SLR, during a training exercise as part of the Gulf War's Operation Desert Shield

United States Marine with a British L1A1 SLR, during a training exercise as part of the Gulf War's Operation Desert Shield- Eight Malaysian soldiers with L1A1 rifles in their headquarters, near the airport in Mogadishu during Operation Restore Hope

A female soldier of the Rejimen Askar Wataniah with a L1A1 SLR, circa 1990s.

A female soldier of the Rejimen Askar Wataniah with a L1A1 SLR, circa 1990s. An Indian BSF Personnel carrying a 1A1 rifle in West Bengal during election,2009

An Indian BSF Personnel carrying a 1A1 rifle in West Bengal during election,2009

Conflicts

The L1A1 self-loading rifle has been used in the following conflicts:

- Malayan Emergency[39]

- Suez Crisis[39]

- Jebel Akhdar War[40]

- Aden Emergency[40]

- Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation[41]

- Congo Crisis[42]

- Vietnam War[43]

- Dhofar Rebellion[44]

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1965[21]

- Communist insurgency in Malaysia

- Cambodian Civil War

- The Troubles[45]

- Rhodesian Bush War[46]

- Biafran War

- Bangladesh Liberation War[47]

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1971[21]

- Soviet–Afghan War[48]

- Falklands War[39]

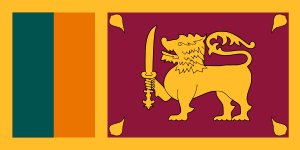

- Sri Lankan Civil War[21]

- Sri Lankan 1971 Communist insurgency

- Sri Lankan 1987-89 Communist insurgency

- Bougainville Civil War[49]

- Gulf War[39]

- Sierra Leone Civil War[50]

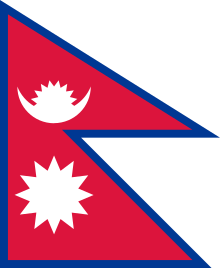

- Nepalese Civil War[51]

- Kargil War[21]

- 2008 Mumbai attacks[52]

- 2013 Lahad Datu standoff

Users

Former users

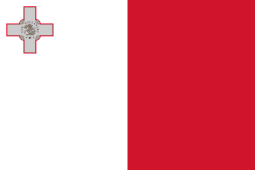

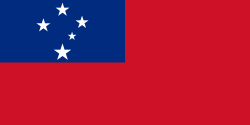

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

- AR-10 – An American 7.62mm battle rifle design from the same period

- CETME rifle – A Spanish 7.62mm battle rifle

- Heckler & Koch G3 – A German 7.62mm battle rifle derived from the CETME

- M14 – An American 7.62mm battle rifle

- MAS-49 – A 7.5mm French semi-automatic battle rifle

- Small Arms Weapons Effects Simulator - Infrared training device used in the 1980s

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to L1A1. |

- Notes

- Especially on the American surplus market.

- During the Cold War, the British SUIT was copied by the Soviet Union and designated the 1P29 telescopic sight.

- Citations

- "FN FAL". world.guns.ru. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Army Code No. 12258, "User Handbook for Rifle, 7.62mm, L1A1 and 0.22 incle calibre, L12A1 Conversion Kit, 7.62mm Rifle

- Small Arms Illustrated, 2010

- Rottman 1993, p. 20.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (23 May 1993). Armies of the Gulf War. Osprey Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-85532-277-6.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (26 January 2017). Vietnam War US & Allied Combat Equipments. Elite 216. Osprey Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 9781472819055.

- "When Government Issue Wasn't Enough: The Australian "B*TCH" Variant of the SLR -". 16 October 2018.

- Palazzo (2011), p. 49.

- Chanoff and Toai 1996, p. 108.

- "FAL STG-58 - 7.62x51". 50AE.net. Archived from the original on 20 June 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- "Lithgow Small Arms Factory Museum". www.lithgowsafmuseum.org.au. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- http://www.1stbn83rdartyvietnam.com/Australia_New%20Zealand/FN-FAL-L1A1_Rifle.pdf

- Stevens, R. Blake. (1993) The FAL Rifle, Collector Grade Publications. Quote from inside jacket cover.

- "FN C1A1 Sniper Rifle – www.captainstevens.com". Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Service Rifles". Canadiansoldiers.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Ezell, 1988, p. 83

- "Rifle 7.62mm 1A1 | ORDNANCE FACTORY TIRUCHIRAPPALLI | Government of India". 23 February 2020. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "FN FAL Rifles | FN Fal Review". 28 October 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Rifle 7.62 MM 1A1". Indian Ordnance Factory Board. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "OFB 7.62 mm 1A1 and 1C rifles (India), Rifles". IHS Jane's. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Cashner (2013), p. 51.

- "Bayonets of India". worldbayonets.com. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Cashner (2013), p. 20.

- https://pib.gov.in/newsite/erelcontent.aspx?relid=84268

- "7.62mm SLR | Defence Research and Development Organisation - DRDO|GoI". www.drdo.gov.in. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- http://www.nzdf.mil.nz/downloads/pdf/force4nz/force4nz_issue5_feb16.pdf

- "L1A1 Self Loading Rifle | VietnamWar.govt.nz, New Zealand and the Vietnam War". vietnamwar.govt.nz. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Cashner (2013), p. 53.

- "Gunman's stash included former army rifles". Stuff. 8 July 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Firearms in the RNZN". 10 December 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- J., Dougherty, Martin (2011). Small arms visual encyclopedia. London: Amber Books. p. 222. ISBN 9781907446986. OCLC 751804871.

- Cashner (2013), p. 15.

- "Self Loading Rifle L1A1: The European "Black Rifle"". www.smallarmsreview.com. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Tilstra, Russell C. (21 March 2014). The Battle Rifle: Development and Use Since World War II. McFarland. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7864-7321-2.

- Cashner (2013), p. 13.

- "FN FAL: The 'Free World's' right arm". Guns.com. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Army Code No 12258 (Revised 1977): User Handbook for Rifle, 7.62mm, L1A1 and 0.22-inch caliber, L12A1 Conversion Kit, 7.62mm Rifle

- "Luxembourg Defence Technologie". luxdeftec.lu (in German). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- Cashner (2013), p. 34.

- Cashner (2013), p. 36.

- McNab, Chris (2002). 20th Century Military Uniforms (2nd ed.). Kent: Grange Books. p. 243. ISBN 1-84013-476-3.

- Abbot, Peter (February 2014). Modern African Wars: The Congo 1960–2002. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-1782000761.

- Cashner (2013), pp. 52-55.

- Cashner (2013), pp. 38-39.

- Cashner (2013), p. 40.

- Cashner (2013), pp. 42-43.

- "Arms for freedom". 29 December 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Isby, David C. (1990). The War in Afghanistan 1979-1989: The Soviet Empire at High Tide. Concord Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-9623610094.

- "The Real Mr. Pip Harry Baxter on Bougainville - 2". YouTube. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Berman, Eric (December 2000). Re-Armament in Sierra Leone: One Year After the Lome Peace Agreement (PDF). Occasional Paper No. 1. Small Arms Survey. pp. 23, 25.

- "Legacies of War in the Company of Peace: Firearms in Nepal" (PDF). Geneva: Small Arms Survey. May 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Cashner (2013), p. 52.

- "Google Sites". accounts.google.com. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Peterson, Philip (20 July 2011). Standard Catalog of Military Firearms: The Collector's Price and Reference Guide. Gun Digest Books. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-1-4402-1451-6.

- Camilleri, Eric (21 October 2005). "Thank you, AFM". The Times of Malta.

- Graduate Institute of International Studies (2003). Small Arms Survey 2003: Development Denied. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–113. ISBN 978-0199251759.

- World Military and Police Forces (26 May 2013). "Trinidad and Tobago". worldmilitaryintel.blogspot.ca. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Report: Profiling the Small Arms Industry". World Policy Institute. November 2000. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- Bishop (1998)

- Capie, David (2004). Under the Gun: The Small Arms Challenge in the Pacific. Wellington: Victoria University Press. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-0864734532.

- Small Arms Survey (2003). "Living with Weapons: Small Arms in Yemen" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2003: Development Denied. Oxford University Press. p. 174.

- Bangladesh Liberation War 1971: Freedom's Arms, retrieved 18 September 2019

- "Equipment: Weapons". Jamaica Defence Force. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Jackson, Robert (2008). The Malayan Emergency and Indonesian Confrontation: The Commonwealth's Wars 1948-1966. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-84415-775-4.

- "7.62mm calibre L1A1 Self Loading Rifle". New Zealand History online. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- "Deactivated RARE OLD SPEC SLR L1A1 New Zealand Contract - Modern Deactivated Guns - Deactivated Guns". www.deactivated-guns.co.uk. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Jowett, Philip (2016). Modern African Wars (5): The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967-70. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1472816092.

- Jowett 2016, p. 23.

- Jones (2009)

- Cocks, Chris (1 July 2001). Fireforce: One Man's War in the Rhodesian Light Infantry. Covos Day. pp. 139–141. ISBN 1-919874-32-1.

- "1999 - Standard Singapore Military Rifles of the 20th Century". Ministry of Defence, Singapore. September 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- Smith, Chris (October 2003). In the Shadow of a Cease-fire: The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka (PDF). Small Arms Survey.

- Bibliography

- Bishop, Chris. Guns in Combat. Chartwell Books, Inc (1998). ISBN 0-7858-0844-2.

- Cashner, Bob (2013). The FN FAL Battle Rifle. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-903-9.

- Capie, David H. (2004). Under the Gun: The Small Arms Challenge in the Pacific. Australia: Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0864734532.

- Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35th edition (27 January 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5

- Palazzo, Albert. Australian Military Operations in Vietnam, Australian Army Campaigns Series # 3, 2nd edition, Canberra: Army History Unit. (2011) [2009]. ISBN 978-0-9804753-8-8.

External links

- The L1A1 SLR Prototype Rifle and l12A1 .22LR conversion unit

- "The Army's New Rifle (1954)" – A YouTube video from British Pathe News about the introduction of the rifle into the British Army.