Exenatide

Exenatide, sold under the brand name Byetta and Bydureon among others, is a medication used to treat diabetes mellitus type 2.[1] It is used together with diet, exercise, and potentially other antidiabetic medication.[1] It is a less preferred treatment option after metformin and sulfonylureas.[2] It is given by injection under the skin within an hour before the first and last meal of the day.[1] A once-weekly injection version is also available.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɛɡzˈɛnətaɪd/ ( |

| Trade names | Byetta, Bydureon, Bydureon BCise, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605034 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | N/A |

| Metabolism | proteolysis |

| Elimination half-life | 2.4 h |

| Excretion | renal/proteolysis |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.212.123 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C184H282N50O60S |

| Molar mass | 4186.63 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include low blood sugar, nausea, dizziness, abdominal pain, and pain at the site of injection.[1] Other serious side effects may include medullary thyroid cancer, angioedema, pancreatitis, and kidney injury.[1] Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[3] Exenatide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 receptor agonist) also known as incretin mimetics.[1] It works by increasing insulin release from the pancreas and decreases excessive glucagon release.[1]

Exenatide was approved for medical use in the United States in 2005.[1] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £82 for the daily injectable and £73 for the weekly injectable version as of 2019.[2] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$700 and US$789 respectively.[4] In 2017, it was the 260th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[5][6]

Medical use

Exenatide is used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus as an add-on to metformin, a biguanide, or a combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea, or thiazolidinediones such as pioglitazone.[7][8] It is also being evaluated for use in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[9]

The medication is injected subcutaneously twice per day using a filled pen-like device (Byetta), or on a weekly basis with either a pen-like device or conventional syringe (Bydureon). The abdomen is a common injection site.[7][8]

Side effects

The main side effects of exenatide use are gastrointestinal in nature, including acid or sour stomach, belching, diarrhea, heartburn, indigestion, nausea, and vomiting; exenatide is therefore not meant for people with severe gastrointestinal disease. Other side effects include dizziness, headache, and feeling jittery.[10] Drug interactions listed on the package insert include delayed or reduced concentrations of lovastatin, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and digoxin, although this has not been proven to alter the effectiveness of these other medications.

In response to postmarketing reports of acute pancreatitis in patients using exenatide, the FDA added a warning to the labeling of Byetta in 2007.[11][12] In August 2008, four additional deaths from pancreatitis in users of exenatide were reported to the FDA; while no definite relationship had been established, the FDA was reportedly considering additional changes to the drug's labeling.[13] Examination of the medical records of the millions of patients part of the United Healthcare Insurance plans did not show any greater rate of pancreatitis among Byetta users than among diabetic patients on other medications. However, diabetics do have a slightly greater incidence of pancreatitis than do non-diabetics.[14][15]

It also may increase risk of mild sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia.[16]

Additionally, the FDA has raised concerns over the lack of data to determine if the long-acting once-weekly version of exenatide (but not the twice-daily form of exenatide) may increase thyroid cancer risk. This concern comes out of observing a very small but nevertheless increased risk of thyroid cancer in rodents that was observed for another drug (liraglutide) that is in the same class as exenatide. The data available for exenatide showed less of a risk towards thyroid cancer than liraglutide, but to better quantify the risk the FDA has required Amylin to conduct additional rodent studies to better identify the thyroid issue. The approved form of the once weekly exenatide [Bydureon] has a black box warning discussing the thyroid issue. Eli Lilly has reported they have not seen a link in humans, but that it cannot be ruled out. Eli Lilly has stated the drug causes an increase in thyroid problems in rats given high doses.[17]

In March 2013, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication announcing investigations into incretin mimetics due to findings by academic researchers.[18] A few weeks later, the European Medicines Agency launched a similar investigation into GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors.[19]

Mechanism of action

Exenatide binds to the intact human Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) in a similar way to the human peptide glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1); exenatide bears a 50% amino acid homology to GLP-1 and it has a longer half-life in vivo.[20]

Exenatide is believed to facilitate glucose control in at least five ways:

- Exenatide augments pancreas response[21] (i.e. increases insulin secretion) in response to eating meals; the result is the release of a higher, more appropriate amount of insulin that helps lower the rise in blood sugar from eating. Once blood sugar levels decrease closer to normal values, the pancreas response to produce insulin is reduced; other drugs (like injectable insulin) are effective at lowering blood sugar, but can "overshoot" their target and cause blood sugar to become too low, resulting in the dangerous condition of hypoglycemia.

- Exenatide also suppresses pancreatic release of glucagon in response to eating, which helps stop the liver from overproducing sugar when it is unneeded, which prevents hyperglycemia (high blood sugar levels).

- Exenatide helps slow down gastric emptying and thus decreases the rate at which meal-derived glucose appears in the bloodstream.

- Exenatide has a subtle yet prolonged effect to reduce appetite, promote satiety via hypothalamic receptors (different receptors than for amylin). Most people using exenatide slowly lose weight, and generally the greatest weight loss is achieved by people who are the most overweight at the beginning of exenatide therapy. Clinical trials have demonstrated the weight reducing effect continues at the same rate through 2.25 years of continued use. When separated into weight loss quartiles, the highest 25% experience substantial weight loss, and the lowest 25% experience no loss or small weight gain.

- Exenatide reduces liver fat content. Fat accumulation in the liver or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is strongly related with several metabolic disorders, in particular low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides, present in patients with type 2 diabetes. It became apparent that exenatide reduced liver fat in mice,[22] rat[23] and more recently in man.[24]

In 2016 work published showing that it can reverse impaired calcium signalling in steatotic liver cells, which, in turn, might be associated with proper glucose control.[23]

Chemistry

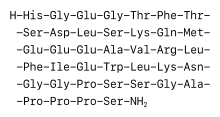

Exenatide is a 39-amino-acid peptide; it is a synthetic version of Exendin-4, a hormone found in the saliva of the Gila monster.[25]

History

Exenatide was first isolated by John Eng in 1992 while working at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in the Bronx, New York.[25] It is made by Amylin Pharmaceuticals and commercialized by AstraZeneca.

Exenatide was approved by the FDA on April 28, 2005 for people whose diabetes was not well-controlled on other oral medication.[26]

Society and culture

53 consolidated lawsuits against manufacturers of "GLP-1/DPP-4 products" were dismissed in 2015.[27]

References

- "Exenatide Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 684–685. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "Exenatide Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Exenatide - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Byetta 10 micrograms solution for injection, prefilled pen - Summary of Product Characteristics". Electronic Medicines Compendium. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Bydureon 2 mg powder and solvent for prolonged-release suspension for injection in pre-filled pen - Summary of Product Characteristics". Electronic Medicines Compendium. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Kim, DS; Choi, HI; Wang, Y; Luo, Y; Hoffer, BJ; Greig, NH (September 2017). "A New Treatment Strategy for Parkinson's Disease through the Gut-Brain Axis: The Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Pathway". Cell Transplantation. 26 (9): 1560–1571. doi:10.1177/0963689717721234. PMC 5680957. PMID 29113464.

- Drugs.com Accessed September 6, 2008.

- 2007 Safety Alerts for Drugs, Biologics, Medical Devices, and Dietary Supplements, from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed August 28, 2008.

- "Byetta (exenatide) FDA warning". Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- Diabetes Drug Tied to New Deaths. The New York Times. August 26, 2008; accessed August 28, 2008.

- Lai SW, Muo CH, Liao KF, Sung FC, Chen PC (September 2011). "Risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes and risk reduction on anti-diabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 106 (9): 1697–704. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.155. PMID 21577242.

- Gonzalez-Perez A, Schlienger RG, Rodríguez LA (December 2010). "Acute pancreatitis in association with type 2 diabetes and antidiabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study". Diabetes Care. 33 (12): 2580–5. doi:10.2337/dc10-0842. PMC 2992194. PMID 20833867.

- Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD, Exenatide-113 Clinical Study Group (November 2004). "Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes". Diabetes Care. 27 (11): 2628–35. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.11.2628. PMID 15504997.

- Silverman E (2010-04-12). "Lilly's Once-Weekly Byetta May Have Cancer Risk". Pharmalot. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010.

- "FDA investigating reports of possible increased risk of pancreatitis and pre-cancerous findings of the pancreas from incretin mimetic drugs for type 2 diabetes". FDA. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 3, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- "European Medicines Agency investigates findings on pancreatic risks with GLP-1-based therapies for type-2 diabetes". EMA. European Medicines Agency Sciences Medicines Health. March 26, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Koole C, Reynolds CA, Mobarec JC, Hick C, Sexton PM, Sakmar TP (April 2017). "Genetically encoded photocross-linkers determine the biological binding site of exendin-4 peptide in the N-terminal domain of the intact human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 292 (17): 7131–7144. doi:10.1074/jbc.M117.779496. PMC 5409479. PMID 28283573.

- Bunck MC, Diamant M, Cornér A, Eliasson B, Malloy JL, Shaginian RM, Deng W, Kendall DM, Taskinen MR, Smith U, Yki-Järvinen H, Heine RJ (May 2009). "One-year treatment with exenatide improves beta-cell function, compared with insulin glargine, in metformin-treated type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial". Diabetes Care. 32 (5): 762–8. doi:10.2337/dc08-1797. PMC 2671094. PMID 19196887.

- Ding X, Saxena NK, Lin S, Gupta NA, Gupta N, Anania FA (January 2006). "Exendin-4, a glucagon-like protein-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, reverses hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice". Hepatology. 43 (1): 173–81. doi:10.1002/hep.21006. PMC 2925424. PMID 16374859.

- Ali ES, Hua J, Wilson CH, Tallis GA, Zhou FH, Rychkov GY, Barritt GJ (September 2016). "The glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue exendin-4 reverses impaired intracellular Ca(2+) signalling in steatotic hepatocytes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1863 (9): 2135–46. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.05.006. PMID 27178543.

- Tushuizen ME, Bunck MC, Pouwels PJ, van Waesberghe JH, Diamant M, Heine RJ (October 2006). "Incretin mimetics as a novel therapeutic option for hepatic steatosis". Liver International. 26 (8): 1015–7. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01315.x. PMID 16953843.

- Raufman JP (January 1996). "Bioactive peptides from lizard venoms". Regulatory Peptides. 61 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1016/0167-0115(96)00135-8. PMID 8701022.

- CDER Drug and Biologic Approvals for Calendar Year 2005, from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed August 28, 2008.

- Moylan T (November 11, 2015). "Preemption Summary Judgment Granted In Incretin-Mimetic Multidistrict Litigation". Lexisnexis.

External links

- "Exenatide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- exenatide at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)