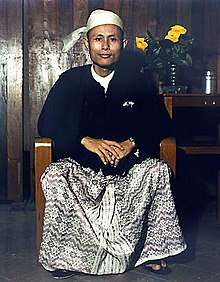

Aung San

Aung San (Burmese: ဗိုလ်ချုပ် အောင်ဆန်း; MLCTS: aung hcan:, pronounced [àʊɰ̃ sʰáɰ̃]; 13 February 1915 – 19 July 1947) was a Burmese politician and revolutionary. He served as the 5th Premier of the British Crown Colony of Burma from 1946 to 1947. Initially he was a communist and later a social democratic politician. He was known as a revolutionary, nationalist, and as the founder of the Tatmadaw (modern-day Myanmar Armed Forces), and is considered as the Father of the Nation of modern-day Myanmar. He was one of the co-founders and first General Secretary of the Communist Party of Burma, one of the armed revolution group during post-colonial Burma after his death.

Major General Aung San | |

|---|---|

အောင်ဆန်း | |

| |

| Premier of British Crown Colony of Burma | |

| In office 26 September 1946 – 19 July 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Paw Tun |

| Succeeded by | U Nu (as Prime Minister) |

| President of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League | |

| In office 27 March 1945 – 19 July 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | U Nu |

| Minister of War in the State of Burma | |

| In office 1 August 1943 – 27 March 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| General Secretary of Communist Party of Burma | |

| In office 15 August 1939 – 1940 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Thakin Soe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Htein Lin 13 February 1915 Natmauk, Magwe, British Burma |

| Died | 19 July 1947 (aged 32) Rangoon, British Burma |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Martyrs' Mausoleum, Myanmar |

| Nationality | Myanmar |

| Political party | Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League Communist Party of Burma |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4, including: Aung San Oo Aung San Suu Kyi |

| Parents | U Pha (father) Daw Suu (mother) |

| Relatives | Ba Win (brother) Sein Win (nephew) Alexander Aris (grandson) |

| Alma mater | Rangoon University Yenangyaung High School |

| Occupation | Politician, major general |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Burma National Army Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League Communist Party of Burma |

| Rank | Major general (highest rank in military at that time) |

He was responsible for bringing about Burma's independence from British rule, but was assassinated six months before independence. During World War Two, he initially collaborated with Japan following their invasion of Burma before swapping sides to the British. He is recognized as the leading architect of independence, and the founder of the Union of Burma. Affectionately known as "Bogyoke" (Major General), Aung San is still widely admired by the Burmese people, and his name is still invoked in Burmese politics to this day.

Aung San's daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, is a stateswoman and politician and a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize who is now serving as State Counsellor and 20th and First Female Minister of Foreign Affairs in Win Myint's Cabinet.

Biography

Early life

Aung San's paternal grandfather, Bo Min Yaung, was from a prominent gentry family in late Kaunbang-era Burma. His extended family had several members in the service of the Burmese kings, including one high-ranking minister during the reign of King Mindon.[1] Bo Min Yaung participated in a rebellion following the Third Anglo-Burmese War, for which he was beheaded.[2]

Aung San was born to U Phar, a Myanmar-Chin lawyer, and his wife, Daw Suu, in the small town of Natmauk, Magway District, on 13 February 1915. The family was considered middle-class.[1] The name "Aung San" was given by his elder brother, Aung Than. Aung San received his primary education at a Buddhist monastic school in Natmauk, and secondary education at Yenangyaung High School.

Aung San rarely spoke before the age of eight. While he was a teenager he often spent hours reading and thinking alone, not responding to those around him. In his youth he was generally unconcerned with his appearance and clothing. In his earliest articles, published in the "Opinion" section of The World of Books, he opposed the ideology of Western-style individualism supported by U Thant in favour of a social philosophy based on "standardization of human life".[3] Aung San later became friends with U Thant through their mutual friendship with U Nu.

Struggle for independence

After Aung San entered Rangoon University in 1933, he quickly became a student leader.[4] He was elected to the executive committee of the Rangoon University Students' Union (RUSU). He then became editor of the RUSU's magazine Oway (Peacock's Call).[5] Aung San was described by contemporary students as being charismatic and keenly interested in politics. While he was enrolled in university his heroes included Abraham Lincoln, the nationalist nineteenth-century Mexican politician Benito Juarez, and Edmund Burke, whose parliamentary speeches he memorized.[1]

In February 1936 he was threatened with expulsion from the university, along with U Nu, for refusing to reveal the name of the author of the article "Hell Hound at Large", which criticized a senior university official.[6] After refusing to give the name of the student who had authored the article Aung San was expelled from the university. His friend U Nu was also expelled for giving anti-British speeches, leading to the three month long Second University Students' Strike, after which the university authorities subsequently retracted their expulsions.[7] In 1938 Aung San was elected president of both the Rangoon University Student Union (RUSU) and the All-Burma Students Union (ABSU), formed after the strike spread to Mandalay.[6] In the same year, the government appointed him as a student representative on the Rangoon University Act Amendment Committee.

In October 1938, Aung San left his law classes and entered national politics. At this point, he was anti-British and staunchly anti-imperialist. He became a Thakin (lord or master—a politically motivated title that proclaimed that the Burmese people were the true masters of their country, not the colonial rulers who had usurped the title for their exclusive use) when he joined the Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association). He acted as its general secretary until August 1940. While in this role, he helped organize a series of countrywide strikes that became known as ME 1300 Revolution (၁၃၀၀ ပြည့် အရေးတော်ပုံ, Htaung thoun ya byei ayeidawbon), based on the Burmese calendar year.

During the Second World War

In August 1939 Aung San became a founding member and the first Secretary General of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB). Aung San later claimed that his relationship with the CPB was not smooth, since he joined and left the party twice. Shortly after founding the CPB Aung San founded a similar organization, alternatively known as either the "People's Revolutionary Party" or the "Burma Revolutionary Party". This party was Marxist and formed with the goal of supporting Burmese independence against the British. It survived, and was reformed into the Socialist Party following World War II.[8]

Following the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 Aung San helped to found another nationalist organization, the Freedom Bloc, by forming an alliance between the Dobama, the All Burma Students Union, politically active monks, and Dr. Ba Maw's Poor Man's Party.[9]. Dr. Ba Maw served as the "dictator" ("anarshin") of the Freedom Bloc, while Aung San worked under him as the group's general secretary. The group's goals were organized around the idea of taking advantage of the war to gain Burmese independence.[10]

In March 1940, he attended the Indian National Congress Assembly in Ramgarh, India. However, the government issued a warrant for his arrest due to Thakin attempts to organize a revolt against the British and he had to flee Burma.[6] He went first to China, seeking assistance from the nationalist government of the Kuomintang,[11] but he was intercepted by the Japanese military occupiers in Amoy, and was convinced by them to go to Japan instead.[12]

Whilst Aung San was in Japan, the Blue Print for a Free Burma, which has been widely but mistakenly attributed to him, was drafted.[13] In February 1941, Aung San returned to Burma, with an offer of arms and financial support from the Fumimaro Konoe government of Japan. He returned briefly to Japan to receive more military training, along with the first batch of young revolutionaries who came to be known as the Thirty Comrades. On 26 December 1941, with the help of the Minami Kikan, a secret intelligence unit that was formed to close the Burma Road and to support a national uprising and that was headed by Suzuki Keiji, he founded the Burma Independence Army (BIA) in Bangkok, Thailand. It was aligned with Japan for most of World War II.</ref>Smith 58-60</ref>

The capital of Burma, Rangoon (also known as Yangon), fell to the Japanese in March 1942 (as part of the Burma Campaign). The BIA formed an administration for the country under Thakin Tun Oke that operated in parallel with the Japanese military administration until the Japanese disbanded it. In July, the disbanded BIA was re-formed as the Burma Defense Army (BDA). Aung San was made a colonel and put in charge of the force.[6] He was later invited to Japan, and was presented with the Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Hirohito.[6]

On 1 August 1943, the Japanese declared Burma an independent nation – State of Burma – under Ba Maw. Aung San was appointed War Minister, and the army was again renamed, this time as the Burma National Army (BNA).[6] Aung San soon became doubtful about Japanese promises of true independence and of Japan's ability to win the war. As William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim put it:

It was not long before Aung San found that what he meant by independence had little relation to what the Japanese were prepared to give—that he had exchanged an old master for an infinitely more tyrannical new one. As one of his leading followers once said to me, "If the British sucked our blood, the Japanese ground our bones!" He became more and more disillusioned with the Japanese, and early in 1943 we got news from Seagrim, a most gallant officer who had remained in the Karen Hills at the ultimate cost of his life, that Aung San's feelings were changing. On 1 August 1944 he was bold enough to speak publicly with contempt of the Japanese brand of independence, and it was clear that, if they did not soon liquidate him, he might prove useful to us. ... At our first interview, Aung San began to take rather a high hand. ... I pointed out that he was in no position to take the line he had. I did not need his forces; I was destroying the Japanese quite nicely without their help, and could continue to do so. I would accept his help and that of his army only on the clear understanding that it implied no recognition of any provisional government. ... The British Government had announced its intention to grant self-government to Burma within the British Commonwealth, and we had better limit our discussion to the best method of throwing the Japanese out of the country as the next step toward self-government.[14]

Aung San made plans to organize an uprising in Burma and made contact with the British authorities in India, in cooperation with the Communist leaders Thakin Than Tun and Thakin Soe. On 27 March 1945, he led the BNA in a revolt against the Japanese occupiers and helped the Allies defeat the Japanese.[15] 27 March came to be commemorated as Resistance Day, until the military regime renamed it "Tatmadaw (Armed Forces) Day".

After the war

After the return of the British, who established a military administration, the Anti-Fascist Organisation (AFO), formed in August 1944, was transformed into a united front, comprising the BNA, the Communists and the Socialists, and renamed the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL). The Burma National Army was renamed the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF) and then gradually disarmed by the British as the Japanese were driven out of various parts of the country. The Patriotic Burmese Forces, while disbanded, were offered positions in the Burma Army under British command according to the Kandy conference agreement with Lord Louis Mountbatten in Ceylon in September 1945. Aung San was offered the rank of Deputy Inspector General of the Burma Army, but he declined it in favor of becoming a civilian political leader and the military leader of the Pyithu yèbaw tat (People's Volunteer Organisation or PVO).[16]

In January 1946, Aung San became the President of the AFPFL following the return of civil government to Burma the previous October. In September, he was appointed Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council or 5th Premier of British-Burma Crown Colony by the new British Governor Sir Hubert Rance, and was made responsible for defence and external affairs. Rance and Mountbatten took a very different view from the former British Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, and also Winston Churchill, who had called Aung San a "traitor rebel leader". A rift had already developed inside the AFPFL between the Communists and Aung San, leading the nationalists and Socialists, which came to a head when Aung San and others accepted seats on the Executive Council. The rift culminated in the expulsion of Thakin Than Tun and the CPB from the AFPFL.[17]

Aung San was to all intents and purposes Prime Minister, although he was still subject to a British veto. On 27 January 1947, Aung San and the British Prime Minister Clement Attlee signed an agreement in London guaranteeing Burma's independence within a year; Aung San had been responsible for its negotiation.</ref>Smith 77</ref> At a press conference during a stopover in Delhi, he stated that the Burmese wanted "complete independence" and not dominion status, and that they had "no inhibitions of any kind" about "contemplating a violent or non-violent struggle or both" in order to achieve it. He concluded that he hoped for the best, but was prepared for the worst.[6]

Two weeks after the signing of the agreement with Britain, Aung San signed an agreement at the Panglong Conference on 12 February 1947 with leaders from other national groups, expressing solidarity and support for a united Burma.[18][19] Karen representatives played a relatively minor role in the conference and, as subsequent rebellions revealed, remained alienated from the new state. U Aung Zan Wai, U Pe Khin, Major Aung, Sir Maung Gyi, Dr Sein Mya Maung, and Myoma U Than Kywe were among the negotiators of the historic Panglong Conference negotiated with Aung San and other ethnic leaders in 1947. These leaders unanimously decided to join the Union of Burma.

In the general election held in April 1947, the AFPFL won 176 out of the 210 seats in the Constituent Assembly, while the Karens won 24, the Communists 6, and Anglo-Burmans 4.[20] In July, Aung San convened a series of conferences at Sorrenta Villa in Rangoon to discuss the rehabilitation of Burma.

Assassination

On 19 July 1947, a gang of armed paramilitaries of former Prime Minister U Saw[21] broke into the Secretariat Building in downtown Rangoon during a meeting of the Executive Council (the shadow government established by the British in preparation for the transfer of power) and assassinated Aung San and six of his cabinet ministers, including his elder brother Ba Win, father of Sein Win, leader of the government-in-exile, the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB). A cabinet secretary and a bodyguard were also killed. U Saw was subsequently tried and hanged.

Many mysteries still surround the assassination. There were rumours of a conspiracy involving the British—a variation on this theory was given new life in an influential, but sensationalist, documentary broadcast by the BBC on the 50th anniversary of the assassination in 1997. What did emerge in the course of the investigations at the time of the trial, however, was that several low-ranking British officers had sold firearms to a number of Burmese politicians, including U Saw. Shortly after U Saw's conviction, Captain David Vivian, a British Army officer, was sentenced to five years' imprisonment for supplying U Saw with weapons. Vivian escaped from prison during the Karen uprising in Insein in early 1949. Little information about his motives was revealed during his trial or after the trial.[22]

Family

While he was War Minister in 1942, Aung San met and married Khin Kyi, and around the same time her sister met and married Thakin Than Tun, the Communist leader. Aung San and Khin Kyi had four children.

Their youngest surviving child, Aung San Suu Kyi, is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, currently serving as State Counsellor, the first female Minister of Foreign Affairs, and leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD). Their second son, Aung San Lin, died at age eight, when he drowned in an ornamental lake in the grounds of the house. The elder, Aung San Oo, is an engineer working in the United States and has disagreed with his sister's political activities.

Their youngest daughter, Aung San Chit, born in September 1946, died on 26 September 1946, the same day Aung San got into Governor's Executive council, a few days after her birth.[23] Aung San's wife Daw Khin Kyi died on 27 December 1988.

Legacy

For his independence struggle and uniting the country as a single entity, he is revered as the architect of modern Burma and a national hero. His legacy assured his daughter's rise as a non-violence icon during the 8888 Uprising against military junta. A Martyrs' Mausoleum was built at the foot of the Shwedagon Pagoda and 19 July was designated Martyrs' Day (Azani nei), a public holiday. His literary work entitled Burma's Challenge was likewise popular.

Aung San's name had been invoked by successive Burmese governments since independence, until the military regime in the 1990s tried to eradicate all traces of Aung San's memory. Nevertheless, several statues of him adorn the former capital Yangon and his portrait still has a place of pride in many homes and offices throughout the country. Scott Market, Yangon's most famous, was renamed Bogyoke Market in his memory, and Commissioner Road was retitled Bogyoke Aung San Road after independence. These names have been retained. Many towns and cities in Burma have thoroughfares and parks named after him. His portrait was held up across the nation during the 8888 Uprising in 1988 and used as a rallying point.[24] Following the 8888 Uprising, the government redesigned the national currency, the kyat, removing his picture and replacing it with scenes of Burmese life.

On 4 January 2020, to mark the 72nd anniversary of Independence Day, the Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM) started distributing the new 15 cm by 7 cm 1,000-kyat notes displaying Aung San and the Parliament on the other side.[25]

Names of Aung San

- Name at birth: Htein Lin (ထိန်လင်း)

- As student leader and a thakin: Aung San (သခင်အောင်ဆန်း)

- Nom de guerre: Bo Teza (ဗိုလ်တေဇ)

- Japanese name: Omoda Monji (面田紋次)

- Chinese name: Tan Lu Shaung

- Resistance period code name: Myo Aung (မျိုးအောင်), U Naung Cho (ဦးနောင်ချို)

- Contact code name with General Ne Win: Ko Set Pe (ကိုဆက်ဖေ)

References

Citations

- Thant 213

- Aung Zaw

- Thant 214

- Maung Maung (1962). Aung San of Burma. The Hauge: Martinus Nijhoff for Yale University. pp. 22, 23.

- Smith 90

- Aung San Suu Kyi (1984). Aung San of Burma. Edinburgh: Kiscadale 1991. pp. 1, 10, 14, 17, 20, 22, 26, 27, 41, 44.

- Smith 54

- Smith 56-57

- Lintner The Rise and Fall of the Communist Party of Burma

- Thant 217

- Stewart, Whitney. (1997). Aung San Suu Kyi: fearless voice of Burma. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8225-4931-4

- Smith 57

- Gustaaf Houtman, In Kei Nemoto (ed) – Reconsidering the Japanese military occupation in Burma (1942–45) (30 May 2007). "Aung San's lan-zin, the Blue Print and the Japanese Occupation of Burma" (PDF). Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA), Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. pp. 179–227. ISBN 978-4-87297-9640. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008.

- Field Marshal Sir William Slim, Defeat into Victory, Cassell & Company, 2nd edition, 1956

- Smith 65

- Smith 66, 69

- Smith 62-63, 68

- Smith 78

- "The Panglong Agreement, 1947". Online Burma/Myanmar Library.

- Appleton, G. (1947). "Burma Two Years After Liberation". International Affairs. Blackwell Publishing. 23 (4): 510–521. JSTOR 3016561.

- MAUNG ZARNI (19 July 2013). "Remembering the martyrs and their hopes for Burma". DVB NEWS. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- "Who Killed Aung San? – an interview with Gen. Kyaw Zaw". The Irrawaddy. August 1997. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- Wintle, Justin (2007). Perfect hostage: a life of Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma's prisoner of conscience. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-60239-266-3.

- Smith 6

- Htwe, Zaw Zaw (7 January 2019). "Gen. Aung San Returns to Myanmar Banknotes After 30-Year Absence". The Irrawaddy.

Sources

- Aung Zaw. "Rewards of Independence Remain Elusive". The Irrawady. January 3 2018.

- Lintner, Bertil. The Rise and Fall of the Communist Party of Burma. Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publication. 1990

- Smith, Martin. Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. 1991.

- Thant Myint-U. The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 2008.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Aung San |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Aung San's resolution to the Constituent Assembly regarding the Burmese Constitution, 16 June 1947

- Kin Oung. Eliminate the Elite – Assassination of Burma's General Aung San & his six cabinet colleagues. Uni of NSW Press. Special edition – Australia 2011

- http://www.bogyokeaungsanmovie.org/