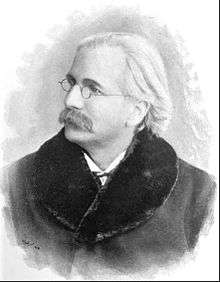

Joseph Parry

Joseph Parry (21 May 1841 – 17 February 1903) was a Welsh composer and musician. Born in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, he is best known as the composer of "Myfanwy" and the hymn tune "Aberystwyth", on which the African song "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika" is said to be based. Parry was also the first Welshman to compose an opera; his composition, Blodwen, was the first opera in the Welsh language.

.jpg)

Born into a large family, Parry left school to work in the local coal mines when he was nine years of age. He then went to work at the Cyfarthfa Ironworks, where his father was also employed. In 1854 the family emigrated to the United States, settling at Danville, Pennsylvania, where Parry again found employment at an iron works.

Though Parry had a great interest in music, he had no opportunity to study it until there was a temporary closure of the Rough and Ready Iron Works. Some of his co-workers were also musicians, and they offered music lessons while the iron works was closed. Parry joined a music sight-reading class taught by one of the men. He continued to study harmony with another co-worker, and learned how to read and write while he was learning about harmony.

Parry soon began submitting compositions to eisteddfodau in Wales and the United States and winning awards. During a return visit to Wales for the National Eisteddfod at Llandudno, Parry was offered two music scholarships, but was unable to accept due to family obligations. A fund was established for the support of Parry and his family while he studied music.

Parry went on to receive a Doctorate in Music from the University of Cambridge; he was the first Welshman to receive Bachelor's and Doctor's degrees in music from the University. He returned to Wales in 1874 to become the first Professor of Music at Aberystwyth University, later accepting a position at Cardiff University.

Life

Early years

Parry was born in Merthyr Tydfil in 1841, the seventh of eight children of Daniel and Elizabeth Parry (née Richards).[1][2][3][lower-alpha 1] The family was musically inclined, with all family members singing in the chapel choir.[5] Parry's mother, who performed at church functions, was remembered for her fine voice; two of Parry's sisters, Elizabeth and Jane, and a brother, Henry, gained some prominence in the United States as vocalists.[6][7] He left school at age nine to work in the mines as the family needed the income. Young Parry worked a 56-hour week for twelve and a half pence while at the mine.[2][8][9] By age 12, Parry was working at the puddling furnaces of the Cyfarthfa Ironworks, where his father also worked.[1][6][5]

Parry's father, Daniel, emigrated to the United States in 1853; the rest of the family followed in 1854.[5] Like his father and brother, Parry became a worker at the Rough and Ready Iron Works in Danville, Pennsylvania.[2][5][1][8][10] Danville had a large Welsh community and he became involved in strengthening Welsh culture locally, attending the Congregational Chapel and the Sunday school.[11][12] Parry also served as the organist for the Mahoning Presbyterian Church in Danville; the organ he played is still in service.[13] Although he had sung in church choirs in Wales and the United States, Parry received no formal music lessons until he was 17 and living in Danville.[1][lower-alpha 2]

Parry's opportunity to study music came in the form of a temporary closure of the iron works where he was employed. Parry had the good fortune to become friendly with three fellow workers who were also musicians. During rest periods, the three often would sing. Parry listened with interest at first, later joining in.[10] One of the men started a music sight-reading class while the iron works was closed; Parry joined this class and became a fine sight-reader. His interest in harmony made him want to study that also. One of his other co-workers agreed to take Parry as a pupil.[10][14] Young Parry was unable to read or write at the time he began harmony studies. The teacher patiently blended reading lessons with principles of harmony, and Parry quickly became skilled at both; the teacher often found it hard to keep up with his pupil.[14] During this time, Parry also learned to play the harmonium.[5]

Return to Wales

.jpg)

Parry competed in the eisteddfod at Utica in 1861, and took first prize for Temperance Vocal March.[1] Curious as to how his music would be received in his native Wales, in 1864, he sent an anthem to the National Eisteddfod of Wales at Llandudno. The adjudicators awarded him first prize, believing he was a professional musician. In 1865, Parry again prepared an entry, but this time he travelled to the contest in Aberystwyth. Parry's anthem entry was lost in the post, so it could not be judged. Instead, he was given a seat in the Gorsedd and the title "Pencerdd America" ("Chief Musician of America").[7]

During this visit, Parry and his friends who had accompanied him to Wales travelled the country giving concerts of Parry's own works. They were well received throughout the land.[7][15] Parry was offered the opportunity to study for a year under Dr Davies of Swansea, followed by a one-year scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music.[7] He had to refuse both offers since he had a wife and child in the United States dependent on him for support.[7] By 1865, Parry's musical ability had become well known in Wales and in the United States. A fund was established to support Parry and his family while he studied music; donations were received from both countries.[7][1] Parry aided his own cause by giving concerts in Pennsylvania, New York and Ohio.[6][lower-alpha 3]

In August 1868 Parry and his family arrived in England, where he began a three-year study at the Royal Academy of Music under William Sterndale Bennett and Manuel Garcia.[7] During his last year of study at the Royal Academy, Parry appeared before Queen Victoria three times, each time by her special request. The Queen made another request of Parry each time he appeared: that he perform only works he had composed.[10] In 1871, Bennett convinced Parry to enter University of Cambridge for a degree in music.[7][17][lower-alpha 4] While at Cambridge, Parry became the first Welshman to take both the MusB and MusD there.[1] After earning his bachelor's degree, Parry and his family returned to Danville, where he operated a school of music for the next three years.[7][18] When Aberystwyth University established a chair for music, it was offered to Parry; he moved his family back to Wales, becoming the university's first Professor of Music.[7][19][1][lower-alpha 5]

Professor and Doctor of music

Parry worked at Aberystwyth from 1874 to 1881. In addition to his university duties, Parry frequently travelled as an adjudicator and conducting concerts of his compositions.[5][lower-alpha 6][lower-alpha 7] He received his Doctorate from Cambridge in 1878. At the time a candidate was required to compose a short oratorio and to have the work publicly performed; the normal method was to have one of the college Chapel Choirs perform the oratorio. But Parry obtained the services of many Welsh singers; 100 made the trip to Cambridge to perform Parry's oratorio.[7][8][22] When Parry resigned his position at Aberystwyth University in 1880, he opened his own academy of music in the town.[23][24]

In 1881, the Parry family left Aberystwyth for Swansea, where Parry became the organist at Ebenezer Chapel and was head of a musical college he founded.[7][8][25][26] When he was offered a chair at Cardiff University in 1888, Parry and his family moved to the nearby town of Penarth. He lectured and taught at the university and was known as "Y Doctor Mawr" ("The Great Doctor").[27][7][8] Parry also accepted a position as the organist at Christ Church Congregational Church in Penarth.[28][29]

Parry became a candidate for principal of the Guildhall School of Music in 1896; the vacancy was due to the death of Sir Joseph Barnby.[30] Officials of the city of Cardiff, colleagues and students at Cardiff University, as well as Parry's former teachers wrote letters to the School of Music Committee in support of his election to the position.[31] There were 38 applicants for the position; the field was reduced to two candidates through a series of ballots by the Court of Common Council. Parry was no longer under consideration after the first round of reductions.[32] He remained at the university and continued his work as an eisteddfod adjudicator, a conductor at Cymanfaoedd Canu, and as a performer and lecturer throughout Wales and the United States until the time of his death.[5]

Personal life and characteristics

In 1861, Parry married Jane Thomas.[lower-alpha 8] She was the daughter of Welsh immigrants and the sister of Gomer Thomas, who published many of Parry's early compositions.[5][10][33][34] The couple had three sons and two daughters. The older children were born when the family was still living in Danville; only Parry's youngest child was born in Wales.[23][35][36] Two of Parry's three sons died after the family moved to Penarth. Parry's youngest son, William, died in 1892; his oldest son, Joseph Haydn, died two years later.[37][38][39] While all of Parry's children are said to have had musical talent, his eldest, Joseph Haydn, followed in his father's footsteps as a composer and teacher.[39][40][lower-alpha 9]

Later in 1894, Parry and his wife hoped a trip to the US would help ease some of the sadness over the deaths of their two sons.[43] Parry had last visited the United States on a vocal concert tour in 1880.[44][45] Though the Parrys would be visiting family, he believed he should be available to the public during the visit since many people in the US had helped him financially when he was studying music in England.[43]

Parry asked an old friend to notify the Welsh community in the United States that he would be visiting and would adjudicate at eisteddfodau, lecture or lead cymanfaoedd canu if desired. The community could arrange for Parry to visit by contacting Rev. Thomas Edwards of Edwardsville, Pennsylvania. Parry and his family visited many cities and towns in the eastern US and were warmly received wherever they went. He kept those back in Cardiff advised of his travels through letters to The Western Mail which were printed by the newspaper.[43] Parry's last journey to the United States in 1898 included a visit to Salt Lake City, where he adjudicated at the third Salt Lake eisteddfod which was held in the Mormon Tabernacle.[46][47][48] His last major work, an opera entitled The Maid of Cefn Ydfa, premiered at the Grand Theatre in Cardiff in late December 1902.[49][7]

Parry was known as a religious man and a hard worker both at the iron works and at his craft. Despite his recognition in Wales and in the United States, he was not a wealthy man. Parry had little aptitude for business. With his permission, a committee of his friends managed his affairs, with Parry creating compositions and his friends tending to the business of publications.[50] Since his compositions were based primarily on Welsh subjects, many of Parry's friends believed it would have been to his advantage to have settled in London, where there were more cosmopolitan experiences to draw inspiration from.[51] In 1859, Parry and his family became citizens of the United States; he was equally proud of being a Welshman and a United States citizen.[10][12][36][52]

David Jenkins, who was a student and assistant to Parry at Aberystwyth, described him as impulsive and unable to criticise his own works, too erratic to be a good conductor and too impatient for all but advanced students, but with a boyish enthusiasm, especially for music.[53][15] Sir Alexander Mackenzie, who also worked with Parry, also noted his great enthusiasm and described him as a man of great musical ability.[54]

Death

About two weeks before his death, Parry became suddenly ill. The medical condition was serious enough to warrant surgery. An operation was performed and a full recovery was expected. Some days after the surgery, it was necessary to perform a second operation due to complications. Parry developed a high fever from blood poisoning a few days after the second surgery. There was a slight rally, but Parry continued to have relapses and grew steadily weaker.[55] Parry, who had planned a tour of Australia and the US for 1904, lay in his sick bed when The Maid of Cefn Ydfa was signed for performances by three opera companies; he was never able to be told of the good news.[7][50][56] Parry died at his Penarth home on 17 February 1903.[55] His last composition was written during his final illness-a tribute to his wife, Jane, entitled Dear Wife.[57]

At least 7,000 people from all parts of the country gathered in Penarth for the funeral of Joseph Parry. They lined the route from Parry's home to Christ Church, where the family worshipped and to the churchyard at St Augustine's. His family and friends were joined by officials from the city of Cardiff, faculty and students from Cardiff University, representatives from the National Eisteddfod and many members of various choirs throughout Wales. Ministers of various denominations were also part of those gathered to pay respects to Parry.[58][59][60] He was buried on the north side of St Augustine's Churchyard, Penarth. Parry's monument is a marble column topped by a lyre with seven strings, with the strings representing the members of Parry's family. Two of the seven strings of the lyre are broken to represent the deaths of his two sons, who died before Parry.[60][19][lower-alpha 10]

Shortly after his death, a national fund was established in Parry's name. This was meant to provide support for his widow, Jane, through an annual annuity; any funds remaining after Jane's death were to be used to provide a national music scholarship named for Parry.[62][lower-alpha 11]

Compositions and other works

Parry was a prolific composer; one of his early works, "My Childhood Dreams", was published while he was living in Danville.[23] Despite his penchant for composing, most of his major works were not commercially successful.[16] His oratorio, Saul of Tarsus, was commissioned for the National Eisteddfod at Rhyl in 1892, and was somewhat successful.[23][40] Parry and others considered it to be his best work; the problem with the oratorio was that it was difficult to perform and that the score for the composition is 305 pages long.[40][46]

Parry is believed to have composed 27 complete works, among them ten operas, five cantatas and two oratorios, as well as countless songs and hymns.[7][64][lower-alpha 12] By the 1890s, Parry was sufficiently well known and was asked to produce many of his works on a commission basis.[40] He dealt with a variety of publishers for some of his works, while he published others himself.[40][lower-alpha 13] Parry published his opera, Blodwen, himself but the reasons for this are not clear.[40] He appears to have done less self-publishing in the 1890s. Part of the reason for this may have been the loss of his printing plates in the Western Mail fire of 1893.[51][65][66]

During Parry's lifetime, many of his works remained unpublished; the shelves of his study held stacks of manuscripts. A friend of Parry's talked with him about the possibility of losing all of his manuscripts if there was a fire and suggested Parry needed a safe to store his manuscripts in. When Parry said he could not afford to buy a safe, the friend gave him one as a gift.[7] Over 100 years after his death, one of his unknown works, Te Deum, was discovered by accident in the National Library of Wales archives.[64][67]

After Parry's death, the Welsh Congregational Church sought to purchase the copyrights of all Parry's works and to publish them.[68] The church was successful in obtaining the copyright to Aberystwyth and more than 60 other hymns and anthems written by Parry.[23] In 1916, Parry's widow, Jane, sold the rights to all works which Parry owned the copyrights of to Snell and Sons, music publishers, for £1150.[40][69][lower-alpha 14]

Aberystwyth

The music, written by Parry, was first published in 1879 by Stephen and Jones in Ail Lyfr Tonau ac Emynau (English tr. Second Book of Tunes and Hymns). It was paired with Charles Wesley's words, "Jesus, Lover of My Soul", and first sung at the English Congregational Church in Portland Street in Aberystwyth, where Parry worked as an organist.[67][71][lower-alpha 15][lower-alpha 16]

Enoch Sontonga worked in a Methodist mission school near Johannesburg. Sontonga, like Parry, was a choirmaster; in 1897, he set new words to Parry's music and called the hymn Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika.[67][lower-alpha 17] Welsh missionaries often brought various copies of hymnals to their African missions; it is believed Parry's hymn reached Africa in this manner.[67] While Sontonga wrote only one stanza of lyrics and a chorus for the song, Samuel Mqhayi composed seven more stanzas in 1927.[67] The song became the national anthem of South Africa and four other African nations.[67]

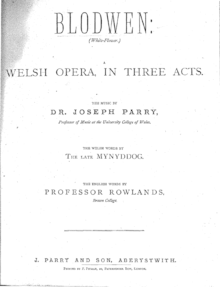

Blodwen

Parry's opera, Blodwen, was first performed in Aberystwyth's Temperance Hall on 21 May 1878, although Parry did not publish it until 1888, while at Swansea.[23] This was the first opera written by a Welsh composer and also the first opera to be performed in Welsh. The opera, with its libretto written by Richard Davies, is set during the time of the Welsh Revolt—the last attempt by the Welsh to preserve their independence.[74][16][23][75]

At the time, very few people in Wales had seen an opera, and they had no idea what it was like. The opera programmes provided explanations, especially that the singers would wear costumes but would not be acting. Those who were members of Welsh nonconformist churches needed reassurance that this was not a theatrical performance, as acting and theatres were held in as much contempt as taverns.[5][7][lower-alpha 18] Parry was raised in the nonconformist Annibynwyr Chapel and adhered to the tenets of his faith for his entire life. The majority of participants in the first performance of Blodwen were music students of Parry; his two older sons were also part of the production, playing piano and harmonium. Before the performance, Parry spoke to the audience. He repeated what had been printed in the programmes: that the participants were not acting and explained to those gathered what an opera was.[5][7][74][76] Despite this, there were some clergymen who were not pleased.[77][78]

Soon after the first performance of Blodwen, a local couple named their baby daughter after the opera's heroine. There were no recorded instances of any children being named Blodwen until after the premiere of Parry's opera. Records show the great popularity of the name for girls and also the popularity of Howell, the name of the hero, for boys.[9] The opera was successful, with a further 500 performances worldwide by 1896.[23][28] Despite the success of Aberystwyth and Myfanwy, Blodwen seems to have been Parry's most popular work while he was living,[28]

Myfanwy

While Parry is most often thought of as the sole creator of the ballad, it was actually the work of three men. At some point, Thomas Walter Price, a poet and journalist, published a poem in English called Arabella.[79][lower-alpha 19] It is believed that Parry wrote the music before the Welsh words of Myfanwy were written by Richard Davies.[79][lower-alpha 20] Parry's work was published in 1875, with Parry selling all rights to the song to a publisher for £12.[79][5] The song was first performed at the first concert of the Aberystwyth and University Musical Society on 28 May 1875, with Parry as the conductor.[81] It remains a standard in repertoires of Welsh male choirs today.[28]

Te Deum

Edward-Rhys Harry reconstructed Parry's setting of the Te Deum taken from the text of The Book of Common Prayer. The manuscript was discovered in the National Library of Wales archives. Parry wrote the manuscript in 1863, while living in Danville. Harry uncovered the manuscript while researching choral traditions at the library. He worked a year at transcribing the original Parry manuscript. The London Welsh Chorale gave the work its world première performance under Harry at St Giles Cripplegate, Barbican, London on 14 July 2012.[64][67][82]

Other works

Parry was also involved in music-related publishing. Beginning in 1861, he was a regular contributor of Tonic sol-fa material to the Welsh music journal, Y cerddor Cymreig.[83] Parry's work with making Tonic sol-fa accessible allowed everyone with an interest in choral work to participate.[84] He edited Cambrian Minstrelsie (A National Collection of Welsh Songs) in 1893.[85] He also compiled Dr Parry's Book of Songs, which was a collection of his own works, and wrote Elfenau Cerddoriaeth ("Elements of Music"), a Welsh handbook on theory, in 1888.[23][86][87] In 1895, Parry entered into an agreement with an American music publishing firm, the John Church Company. The company published some of Parry's songs along with English translations of poems by Heinrich Heine. The translations were done by poets of note, including James Thomson. Since it is doubtful that Parry was familiar with Heine's work, there is the possibility that Parry was commissioned by the company to write the songs during an extensive US trip he had made the year before.[40]

After his move to Penarth, Parry became involved in journalism, writing regular columns for both The Cardiff Times and The South Wales Weekly News. He also did some writing for The Western Mail.[5] In his later years, Parry wrote an autobiography which has been described as inaccurate; he never published the information. The National Library of Wales acquired this manuscript in 1935 from Edna Parry Waite, Parry's daughter and his last surviving child.[70] The National Library published Parry's writings as a bilingual book, The Little Hero-the Autobiography of Joseph Parry, in 2004.[88][89]

Additionally Parry wrote what might very well be the first original work for brass band by an established composer, his 'Tydfil Overture' (c. 1874-80 - i.e. pace Percy Fletcher's 'Labour and Love' of 1913). It has been recorded by the John Wallace Collection.

Legacy

Britain

In 1947, another son of Merthyr Tydfil, Jack Jones, based his novel, Off to Philadelphia in the Morning , on the events in the life of Joseph Parry.[27][90] The book became a BBC three-part presentation of the same name in 1978.[91][92] Jones never offered the book as anything except a work of fiction; despite this, some aspects of the novel have been misconstrued as fact.[88]

The centenary of Parry's death was marked by an open air concert in Merthyr Tydfil's Cyfarthfa Park featuring performances of Parry's works.[93] The concert was recorded on 28 July 2002 by Welsh television production company Avanti Media.[94] It was broadcast by S4C on 17 February 2003. A great-granddaughter of Parry's, who was a professional opera singer, was present for the event.[93][95][lower-alpha 21]

An anthem Parry composed with the Rev. Robert David Thomas while living in Pennsylvania was performed for the first time in Wales to mark the centenary of the composer's death. There was no record of the anthem, "Cymry Glan Americ", having been performed in Wales; it is not certain if the work, which was written on January 1, 1872 had ever been performed previously. A relative of Rev. Thomas located the composition and shared the information with Geraint Jones, the conductor of the Trefor brass band. Jones and his band performed the anthem on 28 May 2002 in Pwllheli at the centenary of the town hall.[96]

In 2011 conductor Edward-Rhys Harry[97] oversaw the total reconstruction of Parry's oratorio Emmanuel, which was performed by Cor Bro Ogwr and The British Sinfonietta, conducted by Harry, in December of that year.[98][99] In May 2013, Emmanuel was performed in the US for the first time when Harry and Côr Bro Ogwr performed in New York and Philadelphia.[99][100]

Parry's cottage

The cottage at 4 Chapel Row, Merthyr Tydfil, where Parry was born, is now open to the public as a museum.[101] The row of cottages was attached to the Bethesda Chapel, where the family attended services. There are two bedrooms upstairs with the kitchen and another bedroom downstairs. The Parry family lived here with two lodgers until emigrating to the United States in 1854.[1]

The chapel and its attached cottages were slated for demolition in 1977; efforts by the local council and students from Cyfarthfa High School saved the row of cottages, but not the Bethesda Chapel. In 1979, the Merthyr Tydfil Heritage Trust opened the cottage to the public. Exhibitions were installed upstairs in 1986 and restoration of the ground floor was completed in 1990.[1] Parry's home was refurbished in 2016 through funds from a local company and was reopened to the public beginning on what would have been the composer's 175th birthday.[102] The home is now part of the Cyfarthfa Heritage Area.[103][104]

United States

Parry is warmly remembered, particularly at the Mahoning Presbyterian Church in Danville, where he served as organist and choirmaster. Each time he visited the US, Parry returned to the church to play the organ.[105][106] The Susquehanna Valley Welsh Society holds an annual Cymanfa Canu in his honour at the church on the Sunday nearest his May 21 birthday.[33] In 2007, the church's steeple was restored with help from the National Welsh American Foundation. The re-dedication of the church was held on May 21, the birthday of Parry.[107] A plaque has been placed at one of his homes in Danville; the community marked the centenary of his death at the local Danville Festival by a memorial concert of Parry's works.[9]

Notes

- His father was from south of Cardigan and his mother from Kidwelly.[4] Only five of the Parry children survived to adulthood.[5]

- Parry was a member of Rosser Beynon's choir as a small boy and was a member of his church choir in Danville.[7][8]

- Parry became involved with Freemasonry while in Danville; in 1867, he joined Mahoning Lodge No. 224.[16] His 1875 song, Ysgytwad y Llaw (The Handshake) appears to acknowledge his connection with the movement.[16] In 1876, he joined Aberystwyth Lodge No. 1072 and became their organist. After leaving Aberystwyth University and opening his own school of music, Parry's activity with the lodge ended; there are no records of his resuming activity with any lodges in either Swansea or Penarth.[16]

- Bennett had an interest in this young musician as he had been an adjudicator for one of Parry's earlier compositions.[7]

- Parry remained in Wales for the rest of his life.[7]

- The relationship between Parry and the college was less than harmonious. The college hoped to produce teachers of music, not performers. Parry's travel throughout the country for concerts and other musical interests outside of the college seemed "ostentatious" to those in charge. It was also feared, given Parry's reputation in Wales, that mostly music students would apply for studies, thus turning the university into a music school only. In 1878, the college sought to limit Parry's ability to perform publicly to when the college was not in session. When Parry accepted the position at Aberystwyth, his income was cut almost in half. The demands of the college allowed him very little opportunity to make up this difference by concert work.[5]

- The college itself was not on stable financial ground; it was founded with private donations and not receiving any government monies at the time. When the college applied for a government grant, the request was refused. Tuitions did not cover operating expenses and the college building itself had yet to be completed in 1877. The next year, a bazaar was held to raise money to buy an organ for the music department, since there was none.[5][20][21]

- Jane did not speak much Welsh and Parry's mother is said to have been against the marriage because of that. The Parrys were members of the local Welsh-speaking Annibynwyr Chapel. The marriage would mean her son would now be attending the English-speaking Mahoning Presbyterian Church.[5]

- The younger Parry was 29 years old and a professor of music at the Guildhall School at the time of his death. He was also a composer: his most successful work was a comic opera, Cigarette, first performed in 1892.[39][41][42]

- Until the opening of Penarth Cemetery, the churchyard was the only burial site in the town; Christ Church, where Parry was a member, was razed in 1989.[61]

- Jane Parry died at Penarth on 25 September 1918.[63]

- Parry composed at least 400 hymns.[23]

- In Parry's time, a publisher paid a composer a flat fee agreed on by the two parties. There were no royalty payments for copies sold or performances of the composition.[40]

- The rights to these works were purchased from Snell and Sons by the National Library of Wales in 1934.[70]

- Experts on Parry disagree about when the song was written: while Parry was the organist at the church or during his earlier years.[67]

- The church building was sold in the early 1980s and developed into a doctors' surgery and space for a local drama company. During the remodeling, the church organ was offered for sale, but no one wanted to buy it. The developers decided to leave the organ in place and construct a wall in front of it; the organ played by Parry is now part of the doctors' surgery.[72]A plaque in the surgery commemorates the event.[67]

- Parry expert Frank Bott disputes the claim that the Sontonga hymn was based on Parry's music.[73]

- In this era, the various nonconformist chapels often presented dramatized versions of Bible stories. Parry's mother was a regular participant in the biblical presentations at church.[7]

- It is not known when or where Arabella was first published.[79]

- Davies' inspiration for the lyrics may have come from Myfanwy of Dinas Bran,[80]

- Elizabeth Parry is the granddaughter of Joseph Haydn Parry. She was 81 years of age at the time. While she had retired from performing, Parry was still active in producing operas.[95]

References

- Sadie & Sadie 2005, p. 286.

- "Joseph Parry". BBC Wales. 18 November 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Obituary". The Eagle: A Magazine Support by Members of St. John's College. W. Metcalfe: 367. 1903.

joseph parry.

- "Dr. Parry and His Choir at Newport". Monmouthshire Merlin. 21 June 1878. p. 5. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Bott, Frank (2012). "Joseph Parry in Aberystwyth". josephparry.org. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Lee 1912, p. 73.

- "The Late Dr. Joseph Parry". The Musical Herald. J. Curwen & Sons: 67–69. 1 March 1903. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Ambrose, Gwilym Prichard. "Joseph Parry". National Biography of Wales. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Rowlands 2005, p. 47.

- "Dr Parry Is Dead". Danville, Pennsylvania: The Montour American. 18 February 1903. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Sellwood 2014, p. Chapel Row.

- "Joseph Parry". Mahoning Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Sylvester, Joe (4 March 2016). "Mahoning Presbyterian Church organ tells 134 years of stories". The Daily Item. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "John M. Price". The Cambrian. T. J. Griffiths: 139–140. March 1907.

- "The Late Dr Joseph Parry". The Weekly News and Visitors' Chronicle for Colwyn Bay Colwyn Llandrillo Conway Deganwy and Neighbourhood. 20 February 1903. p. 6. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Rowlands 2005, p. 45.

- "Parry, Joseph (PRY870J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Distinguished Success of a Young American Welshman". The Emporia Weekly News. 1 September 1871. p. 1. Retrieved 24 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "St. Augustine's". Parish of Penarth and Llandough. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- "The University College". The Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard. 27 April 1877. p. 5. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "The University College Baraar". The Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard. 21 June 1878. p. 8. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "The Tour of the Welsh Representative Choir". The Western Mail. 14 June 1878. p. 3. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Lee 1912, p. 74.

- Evans 1921, p. 97.

- "Joseph Parry". friends of st augustine. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Ebenezer Chapel, Swansea". Archives Wales. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Sadie & Sadie 2005, p. 287.

- Carradice, Phil (19 May 2011). "Joseph Parry: A Rags to Riches Story". BBC. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Christ Church Congregational Church, Penarth". Archives Wales-Glamorgan Archives. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Guildhall school of Music". The South Wales Daily Post. 16 May 1896. p. 4. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- Evans 1921, pp. 192-199.

- "Election of Sir Joseph Barnby's Successor". Evening Express. 5 June 1896. p. 3. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- "Joseph Parry". Mahoning Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "The Shake of the Hand by Joseph Parry". Gomer Thomas. 1872. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Joseph Parry- Pencerdd America". josephparry.org. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Dr. Joseph Parry". The Western Mail. 18 June 1894. p. 6. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "Penarth-Illness of Dr. Joseph Parry's Youngest Son". The Weekly Mail. 2 April 1892. p. 15. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Death of a Son of Dr Joseph Parry". The South Wales Star. 8 April 1892. p. 8. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Haydn Parry Dead". Evening Express. 29 March 1894. p. 3. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Bott, Frank (2013). "Publishing Joseph Parry's Music". Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Parry, Joseph Haydn (1893). "Cigarette". Robert Cocks & Co. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Death of Mr. J Haydn Parry". South Wales Daily News. 30 March 1894. p. 6. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Bott, Frank. "Parry's 1894 American Tour". josephparry.org. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "A Grand Musical Concert". The Hazleton Sentinel. 23 August 1880. p. 1. Retrieved 24 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dr. Parry's Quartette Party". The Hazleton Sentinel. 31 August 1880. p. 1. Retrieved 24 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dr. Joseph Parry". Salt Lake Herald. 16 July 1898. p. 8. Retrieved 22 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dr. Joseph Parry". South Wales Daily News. 6 August 1898. p. 7. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "Dr. Joseph Parry Home Again". South Wales Daily News. 25 October 1898. p. 6. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "Maid of Cefn Ydfa". Evening Express. 22 December 1902. p. 2. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Dr. Parry Memorial". Wilkes-Barre Record. 2 March 1903. p. 8. Retrieved 30 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dr. Joseph Parry's Death". The Wilkes-Barre Record. 20 February 1903. p. 3. Retrieved 22 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dr Joseph Parry and Welsh Music". South Wales Daily News. 3 April 1894. p. 7.

- Lloyd, John Morgan. "David Jenkins". Welsh Biography Online.

- "Interview With Sir Alexander Mackenzie". The North Wales Express. 27 February 1903. p. 5. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "Death of Dr. Joseph Parry". The Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard. 20 February 1903. p. 6. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Funeral of Dr. Parry". Montour American. 12 March 1903. p. 2. Retrieved 31 May 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Late Dr. Joseph Parry". The Wilkes-Barre Record. 19 December 1903. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Late Dr Parry". Evening Express. 19 February 1903. p. 3. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Funeral of Dr. Joseph Parry". The North Wales Express. 27 February 1903. p. 5. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Dr. Parry Laid to Rest". Wilkes-Barre Record. 11 March 1903. p. 6. Retrieved 1 June 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ings 2016.

- "Dr. Parry Memorial". Barry Herald. 24 April 1903. p. 4. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Dr. Parry's Widow Dead". The Cambria Daily Leader. 27 September 1918. p. 1. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- McLaren, James (14 July 2012). "Joseph Parry's Te Deum: Premiere for lost composition". BBC News. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "Publication of The Western Mail". The Cardiff Times. 10 June 1893. p. 6. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Western Mail & Echo Ltd Records". Archives of Wales. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Morgan, Sion (26 March 2013). "The Welsh hymn and the extraordinary history of Africa's favourite anthem". Wales Online. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Late Dr. Joseph Parry-Proposal to Purchase His Works". Weekly Mail. 4 July 1903. p. 4. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "Snell & Sons Collection of Music Manuscripts". National Library of Wales. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Dr Joseph Parry Manuscripts". National Library of Wales. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Aberystwyth". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- BBC 2005, pp. 1-15.

- Bott, Frank. "Joseph Parry's "Aberystwyth"". josephparry.org. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "Blodwen: The First Welsh Opera". The Aberystwyth Observer. 25 May 1878. p. 4. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Blodwen: A Welsh Opera". The Aberystwyth Observer. 11 May 1878. p. 8. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Blodwen". josephparry.org. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "The Pulpit and the Stage". The Western Mail. 17 June 1890. p. 2. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- "Chapel and Stage". The Western Mail. 23 June 1890. p. 6. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Griffiths, Rhidian, Bott, Frank. "The Birth of Myfanwy". Yr Aradr, the journal of Cymdeithas Dafydd ap Gwilym. Retrieved 26 May 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Myfanwy of Dinas Bran". BBC Wales. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Concern of the Aberystwyth and University Musical Society". The Aberstywyth Observer. 29 May 1875. p. 4. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "William Mathias 'St Teilo' & Joseph Parry 'Te Deum'". London Welsh Chorale. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- Y cerddor Cymreig. WorldCat. OCLC 46490592.

- Morgan 1981, p. 20.

- Parry, Joseph (1893). Cambrian Minstrelsie. Grange. OCLC 10639867.

- Parry, Joseph (1890). Dr Parry's Book of Songs. D. M. Parry. OCLC 498209023.

- Parry, Joseph (1888). Y "Cambrian Series." Cyfres o lyfrau cerddorol addysgiadol ... Rhan 1. Theory. Elfenau cerddoriaeth. Duncan a'i Feibion. OCLC 563634293.

- "Joseph Parry Pencerdd America-books". josephparry.org. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Rhys, Dulais, ed. (2004). The little hero : the autobiography of Joseph Parry = yr Arwr bach : hunangofiant Joseph Parry. National Library of Wales. OCLC 877581057.

- Jones, Jack (1947). Off to Philadelphia in the Morning. H. Hamilton. OCLC 7459277.

- "Off to Philadelphia in the Morning". BBC. 19 September 1978. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "Off to Philadelphia in the Morning". BFI. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Llewellyn, Carl (5 March 2015). "Memories of the open air centenary concert commemorating the death of Dr. Joseph Parry". Côr Meibion Dowlais Male Choir. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Avanti Media English home page". Avanti Media. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- Trainor, Tony (17 February 2003). "Parry's Musical Great Grand-Daughter to Join Centenary Events". Western Mail. Retrieved 11 June 2016 – via Questia.

- Williams, Catrin (11 May 2002). "Arts: Parry's 'Lost' Anthem Aired; MUSIC PREMIERE: Trefor Brass Band to Play American Work at Centenary Concert". Western Mail. Retrieved 11 June 2016 – via Questia.

- "Edward-Rhys Harry". Edward-Rhys Harry.

- "About Edward-Rhys Harry". Edward-Rhys Harry. 2012. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Edward-Rhys Harry, Musical Director". The London Welsh Chorale. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Côr Bro Ogwr, of Brigend Wales, UK Is on tour in the United States". The Welsh Society of Philadelphia. 6 September 2012. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Museums, Galleries and Joseph Parry's Cottage". Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Doors re-open to Merthyr home of Myfanwy composer". ITV News. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Joseph Parry's Cottage". Cyfarthfa Park. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "Heritage". Cyfarthfa Park. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "History". Mahoning Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "Dr Joseph Parry". Evening Express. 6 October 1894. p. 2. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Joseph Parry's Danville Church Restorations". National Welsh American Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

Sources

- "Church Surgery's Secret" (PDF). BBC. 24 November 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Evans, E. Keri (1921). Cofiant Dr. Joseph Parry. Educational Pub. Co., Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ings, David (2016). Penarth History Tour. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-5692-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sir Sidney (1912). Dictionary of National Biography: Neil-Young. Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1981). Rebirth of a Nation: Wales, 1880-1980. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1982-1736-7.

joseph parry.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Rowlands, Eryl Wyn (January 2005). "Joseph Parry-flawed genius?". MQ Magazine. United Grand Lodge of England.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sadie, Julie Anne; Sadie, Stanley (2005). Calling on the Composer. Yale University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-3001-8394-8.

joseph parry.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Sellwood, Kathryn Jane (2014). Merthyr Tydfil Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-1833-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)