Basidiomycota

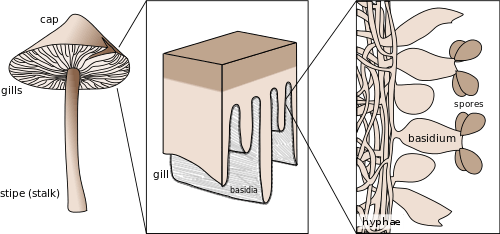

Basidiomycota (/bəˌsɪdioʊmaɪˈkoʊtə/)[2] is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. More specifically, Basidiomycota includes these groups: mushrooms, puffballs, stinkhorns, bracket fungi, other polypores, jelly fungi, boletes, chanterelles, earth stars, smuts, bunts, rusts, mirror yeasts, and the human pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus. Basidiomycota are filamentous fungi composed of hyphae (except for basidiomycota-yeast) and reproduce sexually via the formation of specialized club-shaped end cells called basidia that normally bear external meiospores (usually four). These specialized spores are called basidiospores.[3] However, some Basidiomycota are obligate asexual reproducers. Basidiomycota that reproduce asexually (discussed below) can typically be recognized as members of this division by gross similarity to others, by the formation of a distinctive anatomical feature (the clamp connection), cell wall components, and definitively by phylogenetic molecular analysis of DNA sequence data.

| Basidiomycota | |

|---|---|

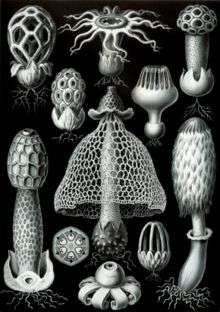

| |

| Basidiomycetes from Ernst Haeckel's 1904 Kunstformen der Natur | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Subkingdom: | Dikarya |

| Division: | Basidiomycota Moore, R.T. 1980[1] |

| Subdivisions/Classes | |

| |

Classification

A recent classification[4] adopted by a coalition of 67 mycologists recognizes three subphyla (Pucciniomycotina, Ustilaginomycotina, Agaricomycotina) and two other class level taxa (Wallemiomycetes, Entorrhizomycetes) outside of these, among the Basidiomycota. As now classified, the subphyla join and also cut across various obsolete taxonomic groups (see below) previously commonly used to describe Basidiomycota. According to a 2008 estimate, Basidiomycota comprise three subphyla (including six unassigned classes) 16 classes, 52 orders, 177 families, 1,589 genera, and 31,515 species.[5]

Traditionally, the Basidiomycota were divided into two classes, now obsolete:

- Homobasidiomycetes (alternatively called holobasidiomycetes), including true mushrooms

- Heterobasidiomycetes, including the jelly, rust and smut fungi

Previously the entire Basidiomycota were called Basidiomycetes, an invalid class level name coined in 1959 as a counterpart to the Ascomycetes, when neither of these taxa were recognized as divisions. The terms basidiomycetes and ascomycetes are frequently used loosely to refer to Basidiomycota and Ascomycota. They are often abbreviated to "basidios" and "ascos" as mycological slang.

Agaricomycotina

The Agaricomycotina include what had previously been called the Hymenomycetes (an obsolete morphological based class of Basidiomycota that formed hymenial layers on their fruitbodies), the Gasteromycetes (another obsolete class that included species mostly lacking hymenia and mostly forming spores in enclosed fruitbodies), as well as most of the jelly fungi. This sub-phyla also includes the "classic" mushrooms, polypores, corals, chanterelles, crusts, puffballs and stinkhorns[6]. The three classes in the Agaricomycotina are the Agaricomycetes, the Dacrymycetes, and the Tremellomycetes.[7]

The class Wallemiomycetes is not yet placed in a subdivision, but recent genomic evidence suggests that it is a sister group of Agaricomycotina.[8][9]

Pucciniomycotina

The Pucciniomycotina include the rust fungi, the insect parasitic/symbiotic genus Septobasidium, a former group of smut fungi (in the Microbotryomycetes, which includes mirror yeasts), and a mixture of odd, infrequently seen, or seldom recognized fungi, often parasitic on plants. The eight classes in the Pucciniomycotina are Agaricostilbomycetes, Atractiellomycetes, Classiculomycetes, Cryptomycocolacomycetes, Cystobasidiomycetes, Microbotryomycetes, Mixiomycetes, and Pucciniomycetes.[10]

Ustilaginomycotina

The Ustilaginomycotina are most (but not all) of the former smut fungi and the Exobasidiales. The classes of the Ustilaginomycotina are the Exobasidiomycetes, the Entorrhizomycetes, and the Ustilaginomycetes.[11]

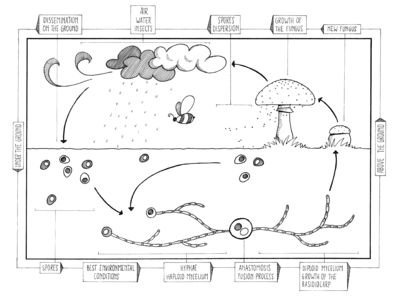

Typical life-cycle

Unlike animals and plants which have readily recognizable male and female counterparts, Basidiomycota (except for the Rust (Pucciniales)) tend to have mutually indistinguishable, compatible haploids which are usually mycelia being composed of filamentous hyphae. Typically haploid Basidiomycota mycelia fuse via plasmogamy and then the compatible nuclei migrate into each other's mycelia and pair up with the resident nuclei. Karyogamy is delayed, so that the compatible nuclei remain in pairs, called a dikaryon. The hyphae are then said to be dikaryotic. Conversely, the haploid mycelia are called monokaryons. Often, the dikaryotic mycelium is more vigorous than the individual monokaryotic mycelia, and proceeds to take over the substrate in which they are growing. The dikaryons can be long-lived, lasting years, decades, or centuries. The monokaryons are neither male nor female. They have either a bipolar (unifactorial) or a tetrapolar (bifactorial) mating system. This results in the fact that following meiosis, the resulting haploid basidiospores and resultant monokaryons, have nuclei that are compatible with 50% (if bipolar) or 25% (if tetrapolar) of their sister basidiospores (and their resultant monokaryons) because the mating genes must differ for them to be compatible. However, there are sometimes more than two possible alleles for a given locus, and in such species, depending on the specifics, over 90% of monokaryons could be compatible with each other.

The maintenance of the dikaryotic status in dikaryons in many Basidiomycota is facilitated by the formation of clamp connections that physically appear to help coordinate and re-establish pairs of compatible nuclei following synchronous mitotic nuclear divisions. Variations are frequent and multiple. In a typical Basidiomycota lifecycle the long lasting dikaryons periodically (seasonally or occasionally) produce basidia, the specialized usually club-shaped end cells, in which a pair of compatible nuclei fuse (karyogamy) to form a diploid cell. Meiosis follows shortly with the production of 4 haploid nuclei that migrate into 4 external, usually apical basidiospores. Variations occur, however. Typically the basidiospores are ballistic, hence they are sometimes also called ballistospores. In most species, the basidiospores disperse and each can start a new haploid mycelium, continuing the lifecycle. Basidia are microscopic but they are often produced on or in multicelled large fructifications called basidiocarps or basidiomes, or fruitbodies), variously called mushrooms, puffballs, etc. Ballistic basidiospores are formed on sterigmata which are tapered spine-like projections on basidia, and are typically curved, like the horns of a bull. In some Basidiomycota the spores are not ballistic, and the sterigmata may be straight, reduced to stubbs, or absent. The basidiospores of these non-ballistosporic basidia may either bud off, or be released via dissolution or disintegration of the basidia.

In summary, meiosis takes place in a diploid basidium. Each one of the four haploid nuclei migrates into its own basidiospore. The basidiospores are ballistically discharged and start new haploid mycelia called monokaryons. There are no males or females, rather there are compatible thalli with multiple compatibility factors. Plasmogamy between compatible individuals leads to delayed karyogamy leading to establishment of a dikaryon. The dikaryon is long lasting but ultimately gives rise to either fruitbodies with basidia or directly to basidia without fruitbodies. The paired dikaryon in the basidium fuse (i.e. karyogamy takes place). The diploid basidium begins the cycle again.

Meiosis

Coprinopsis cinerea is a basidiomycete mushroom. It is particularly suited to the study of meiosis because meiosis progresses synchronously in about 10 million cells within the mushroom cap, and the meiotic prophase stage is prolonged. Burns et al.[12] studied the expression of genes involved in the 15-hour meiotic process, and found that the pattern of gene expression of C. cinerea was similar to two other fungal species, the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. These similarities in the patterns of expression led to the conclusion that the core expression program of meiosis has been conserved in these fungi for over half a billion years of evolution since these species diverged.[12]

Cryptococcus neoformans and Ustilago maydis are examples of pathogenic basidiomycota. Such pathogens must be able to overcome the oxidative defenses of their respective hosts in order to produce a successful infection. The ability to undergo meiosis may provide a survival benefit for these fungi by promoting successful infection. A characteristic central feature of meiosis is recombination between homologous chromosomes. This process is associated with repair of DNA damage, particularly double-strand breaks. The ability of C. neoformans and U. maydis to undergo meiosis may contribute to their virulence by repairing the oxidative DNA damage caused by their host's release of reactive oxygen species.[13][14]

Variations in lifecycles

Many variations occur. Some are self-compatible and spontaneously form dikaryons without a separate compatible thallus being involved. These fungi are said to be homothallic, versus the normal heterothallic species with mating types. Others are secondarily homothallic, in that two compatible nuclei following meiosis migrate into each basidiospore, which is then dispersed as a pre-existing dikaryon. Often such species form only two spores per basidium, but that too varies. Following meiosis, mitotic divisions can occur in the basidium. Multiple numbers of basidiospores can result, including odd numbers via degeneration of nuclei, or pairing up of nuclei, or lack of migration of nuclei. For example, the chanterelle genus Craterellus often has six-spored basidia, while some corticioid Sistotrema species can have two-, four-, six-, or eight-spored basidia, and the cultivated button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. can have one-, two-, three- or four-spored basidia under some circumstances. Occasionally, monokaryons of some taxa can form morphologically fully formed basidiomes and anatomically correct basidia and ballistic basidiospores in the absence of dikaryon formation, diploid nuclei, and meiosis. A rare few number of taxa have extended diploid lifecycles, but can be common species. Examples exist in the mushroom genera Armillaria and Xerula, both in the Physalacriaceae. Occasionally, basidiospores are not formed and parts of the "basidia" act as the dispersal agents, e.g. the peculiar mycoparasitic jelly fungus, Tetragoniomyces or the entire "basidium" acts as a "spore", e.g. in some false puffballs (Scleroderma). In the human pathogenic genus Cryptococcus, four nuclei following meiosis remain in the basidium, but continually divide mitotically, each nucleus migrating into synchronously forming nonballistic basidiospores that are then pushed upwards by another set forming below them, resulting in four parallel chains of dry "basidiospores".

Other variations occur, some as standard lifecycles (that themselves have variations within variations) within specific orders.

Rusts

Rusts (Pucciniales, previously known as Uredinales) at their greatest complexity, produce five different types of spores on two different host plants in two unrelated host families. Such rusts are heteroecious (requiring two hosts) and macrocyclic (producing all five spores types). Wheat stem rust is an example. By convention, the stages and spore states are numbered by Roman numerals. Typically, basidiospores infect host one, also known as the alternate or sexual host, and the mycelium forms pycnidia, which are miniature, flask-shaped, hollow, submicroscopic bodies embedded in the host tissue (such as a leaf). This stage, numbered "0", produces single-celled spores that ooze out in a sweet liquid and that act as nonmotile spermatia, and also protruding receptive hyphae. Insects and probably other vectors such as rain carry the spermatia from spermagonium to spermagonium, cross inoculating the mating types. Neither thallus is male or female. Once crossed, the dikaryons are established and a second spore stage is formed, numbered "I" and called aecia, which form dikaryotic aeciospores in dry chains in inverted cup-shaped bodies embedded in host tissue. These aeciospores then infect the second host, known as the primary or asexual host (in macrocyclic rusts). On the primary host a repeating spore stage is formed, numbered "II", the urediospores in dry pustules called uredinia. Urediospores are dikaryotic and can infect the same host that produced them. They repeatedly infect this host over the growing season. At the end of the season, a fourth spore type, the teliospore, is formed. It is thicker-walled and serves to overwinter or to survive other harsh conditions. It does not continue the infection process, rather it remains dormant for a period and then germinates to form basidia (stage "IV"), sometimes called a promycelium. In the Pucciniales, the basidia are cylindrical and become 3-septate after meiosis, with each of the 4 cells bearing one basidiospore each. The basidiospores disperse and start the infection process on host 1 again. Autoecious rusts complete their life-cycles on one host instead of two, and microcyclic rusts cut out one or more stages.

Smuts

The characteristic part of the life-cycle of smuts is the thick-walled, often darkly pigmented, ornate, teliospore that serves to survive harsh conditions such as overwintering and also serves to help disperse the fungus as dry diaspores. The teliospores are initially dikaryotic but become diploid via karyogamy. Meiosis takes place at the time of germination. A promycelium is formed that consists of a short hypha (equated to a basidium). In some smuts such as Ustilago maydis the nuclei migrate into the promycelium that becomes septate (i.e., divided into cellular compartments separated by cell walls called septa), and haploid yeast-like conidia/basidiospores sometimes called sporidia, bud off laterally from each cell. In various smuts, the yeast phase may proliferate, or they may fuse, or they may infect plant tissue and become hyphal. In other smuts, such as Tilletia caries, the elongated haploid basidiospores form apically, often in compatible pairs that fuse centrally resulting in "H"-shaped diaspores which are by then dikaryotic. Dikaryotic conidia may then form. Eventually the host is infected by infectious hyphae. Teliospores form in host tissue. Many variations on these general themes occur.

Smuts with both a yeast phase and an infectious hyphal state are examples of dimorphic Basidiomycota. In plant parasitic taxa, the saprotrophic phase is normally the yeast while the infectious stage is hyphal. However, there are examples of animal and human parasites where the species are dimorphic but it is the yeast-like state that is infectious. The genus Filobasidiella forms basidia on hyphae but the main infectious stage is more commonly known by the anamorphic yeast name Cryptococcus, e.g. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii.

The dimorphic Basidiomycota with yeast stages and the pleiomorphic rusts are examples of fungi with anamorphs, which are the asexual stages. Some Basidiomycota are only known as anamorphs. Many are yeasts, collectively called basidiomycetous yeasts to differentiate them from ascomycetous yeasts in the Ascomycota. Aside from yeast anamorphs, and uredinia, aecia and pycnidia, some Basidiomycota form other distinctive anamorphs as parts of their life-cycles. Examples are Collybia tuberosa[15] with its apple-seed-shaped and coloured sclerotium, Dendrocollybia racemosa [16] with its sclerotium and its Tilachlidiopsis racemosa conidia, Armillaria with their rhizomorphs,[17] Hohenbuehelia [18] with their Nematoctonus nematode infectious, state[19] and the coffee leaf parasite, Mycena citricolor[17] and its Decapitatus flavidus propagules called gemmae.

Genera included

There are several genera classified in the Basidiomycota that are 1) poorly known, 2) have not been subjected to DNA analysis, or 3) if analysed phylogenetically do not group with as yet named or identified families, and have not been assigned to a specific family (i.e., they are incertae sedis with respect to familial placement). These include:

- Anastomyces W.P.Wu, B.Sutton & Gange (1997)

- Anguillomyces Marvanová & Bärl. (2000)

- Anthoseptobasidium Rick (1943)

- Arcispora Marvanová & Bärl. (1998)

- Arrasia Bernicchia, Gorjón & Nakasone (2011)

- Brevicellopsis Hjortstam & Ryvarden (2008)

- Celatogloea P.Roberts (2005)

- Cleistocybe Ammirati, A.D.Parker & Matheny (2007)

- Cystogloea P. Roberts (2006)

- Dacryomycetopsis Rick (1958)

- Eriocybe Vellinga (2011)

- Hallenbergia Dhingra & Priyanka (2011)

- Hymenoporus Tkalčec, Mešić & Chun Y.Deng (2015)

- Kryptastrina Oberw. (1990)

- Microstella K.Ando & Tubaki (1984)

- Neotyphula Wakef. (1934)

- Nodulospora Marvanová & Bärl. (2000)

- Paraphelaria Corner (1966)

- Punctulariopsis Ghob.-Nejh. (2010)

- Radulodontia Hjortstam & Ryvarden (2008)

- Restilago Vánky (2008)

- Sinofavus W.Y.Zhuang (2008)

- Zanchia Rick (1958)

- Zygodesmus Corda (1837)

- Zygogloea P.Roberts (1994)

References

- Moore, R. T. (1980). "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina. 23: 371.

- "Basidiomycota". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Rivera-Mariani, F.E.; Bolaños-Rosero, B. (2011). "Allergenicity of airborne basidiospores and ascospores: need for further studies". Aerobiologia. 28 (2): 83–97. doi:10.1007/s10453-011-9234-y. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Hibbett, David S.; Binder, Manfred; Bischoff, Joseph F.; Blackwell, Meredith; Cannon, Paul F.; Eriksson, Ove E.; Huhndorf, Sabine; James, Timothy; Kirk, Paul M. (May 2007). "A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi". Mycological Research. 111 (5): 509–547. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.626.9582. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004. PMID 17572334.

- Kirk, Cannon & Stalpers 2008, pp. 78–79

- https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.uoregon.edu/dist/c/8944/files/2014/09/Lecture-7-Ustilaginomycets-1w4kndx.pdf

- Kirk, Cannon & Stalpers 2008, p. 13

- Zajc, J.; Liu, Y.; Dai, W.; Yang, Z.; Hu, J.; Gostinčar, C.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. (Sep 13, 2013). "Genome and transcriptome sequencing of the halophilic fungus Wallemia ichthyophaga: haloadaptations present and absent". BMC Genomics. 14: 617. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-617. PMC 3849046. PMID 24034603.

- Padamsee, M.; Kumar, T. K.; Riley, R.; Binder, M.; Boyd, A.; Calvo, A. M.; Furukawa, K.; Hesse, C.; Hohmann, S.; James, T. Y.; LaButti, K.; Lapidus, A.; Lindquist, E.; Lucas, S.; Miller, K.; Shantappa, S.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Hibbett, D. S.; McLaughlin, D. J.; Spatafora, J. W.; Aime, M. C. (Mar 2012). "The genome of the xerotolerant mold Wallemia sebi reveals adaptations to osmotic stress and suggests cryptic sexual reproduction". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 49 (3): 217–26. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2012.01.007. PMID 22326418.

- Kirk, Cannon & Stalpers 2008, p. 581

- Kirk, Cannon & Stalpers 2008, pp. 717–718

- Burns, C.; Stajich, J. E.; Rechtsteiner, A.; Casselton, L.; Hanlon, S. E.; Wilke, S. K.; Savytskyy, O. P.; Gathman, A. C.; Lilly, W. W.; Lieb, J. D.; Zolan, M. E.; Pukkila, P. J. (September 2010). "Analysis of the Basidiomycete Coprinopsis cinerea reveals conservation of the core meiotic expression program over half a billion years of evolution". PLOS Genetics. 6 (9): e1001135. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001135. PMC 2944786. PMID 20885784.

- Lin, X.; Hull, C. M.; Heitman, J. (April 2005). "Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans". Nature. 434 (7036): 1017–21. Bibcode:2005Natur.434.1017L. doi:10.1038/nature03448. PMID 15846346. S2CID 3195603.

- Michod, R. E.; Bernstein, H.; Nedelcu, A. M. (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Microsoft Word – Machnicki revised for pdf final august 24 Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- LUXGENE.COM: the glow-in-the-dark website

- "Hohenbue". Archived from the original on 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- "8knobs". Archived from the original on 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

Sources

- Kirk, P. M.; Cannon, P. F.; Stalpers, J. A. (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). CABI.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basidiomycota. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Basidiomycota |

- Basidiomycota at the Tree of Life Web Project