Collybia tuberosa

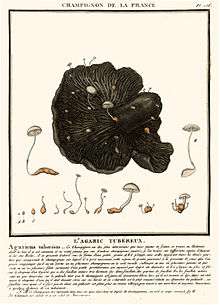

Collybia tuberosa, commonly known as the lentil shanklet or the appleseed coincap, is an inedible species of fungus in the family Tricholomataceae, and the type species of the genus Collybia. Like the two other members of its genus, it lives on the decomposing remains of other fleshy mushrooms. The fungus produces small whitish fruit bodies with caps up to 1 cm (0.4 in) wide held by thin stems up to 5 cm (2.0 in) long. On the underside of the cap are closely spaced white gills that are broadly attached to the stem. At the base of the stem, embedded in the substrate is a small reddish-brown sclerotium that somewhat resembles an apple seed. The appearance of the sclerotium distinguishes it from the other two species of Collybia, which are otherwise very similar in overall appearance. C. tuberosa is found in Europe, North America, and Japan, growing in dense clusters on species of Lactarius and Russula, boletes, hydnums, and polypores.

| Collybia tuberosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. tuberosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Collybia tuberosa | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Agaricus tuberosus Bull. (1786) | |

| Collybia tuberosa | |

|---|---|

float | |

| gills on hymenium | |

| cap is convex or flat | |

| hymenium is adnate | |

| stipe is bare | |

| spore print is white | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: inedible | |

Taxonomy, phylogeny, and naming

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny and relationships of C. tuberosa and closely related fungi based on ribosomal DNA sequences.[2] |

The species was first described under the name Agaricus tuberosus by the French naturalist Jean Bulliard in the 6th volume of his Herbier de la France (1786).[3] Christian Hendrik Persoon called it Agaricus amanitae subsp. tuberosus in his 1799 publication Observationes Mycologicae,[4] while Samuel Frederick Gray referred it to Gymnopus in 1821.[5] It was transferred to Collybia by Paul Kummer in 1886.[6] The species has also been called Microcollybia tuberata in a 1979 publication by Joanne Lennox,[7] but the genus Microcollybia has since been folded into Collybia.[8] Additional taxonomic synonyms include Marasmius sclerotipes Bres. 1881, Chamaeceras sclerotipes (Bres.) Kuntze 1898, and Collybia sclerotipes (Bres.) S.Ito 1950.[1]

Molecular phylogenetic analysis reported in 2001 used RNA sequences to establish that C. tuberosa forms a monophyletic group with C. cookei and C. cirrhata;[2] this finding was later corroborated in a 2006 publication.[9]

The specific epithet tuberosa is derived from the Latin word for "tuberous".[10] The mushroom is commonly known as the "lentil shanklet",[11] or the "appleseed coincap".[12] Samuel Gray called it the "tuberous naked-foot" in his 1821 Natural Arrangement of British plants.[5]

Description

The cap of C. tuberosa ranges in shape from obtusely convex to cushion-shaped with a margin curved inward when young, to flattened in age, with margin curved downward to straight. The cap sometimes has a shallow depression in the center,[13] or a shallow umbo. Its diameter is small, reaching a maximum of 10 mm (0.39 in).[14] The cap surface is dry to moist, smooth to covered with fine soft hairs, and somewhat hygrophanous—changing color depending on the level of hydration. Sometimes the cap margin is pleated or grooved. The center of the cap is pinkish-buff but whitish around the margin, and it becomes whitish overall as it matures. The flesh is thin, and colored whitish to light buff.[13] The mushroom has no distinctive taste or odor, and is considered inedible.[14]

The gills are adnate (bluntly fused to the stem), becoming subdecurrent with age (running slightly down the length of the stem). The gill spacing is close to subdistant, and the individual gills are whitish to pinkish-buff, thin, narrow to moderately broad, and have straight edges. The stem is 10–50 mm (0.4–2.0 in) long by 1–2 mm (0.04–0.08 in), and roughly equal in width throughout its length. It is slender and thread-like, flexible and pliant, with a dry surface. The top of the stem is covered with scales or a fine whitish powder, while the lower portion has hairs ranging from delicate to coarse. The color of the stem is generally whitish to pinkish-buff, but it darkens after it has been handled. The stem interior is pithy, and becomes hollow with age. The stems originate from a dark reddish-brown sclerotium of variable shape, typically measuring 3–12 mm (0.12–0.47 in) by 2–5 mm (0.08–0.20 in). The surface of the sclerotium is initially smooth, but later becomes wrinkled or furrowed; its interior is solid and white.[13] It is often compared to an apple seed in appearance.[12][15] Typically, several sclerotia are connected by thin strands of mycelia.[12] The sclerotium is a resting structure that allows to fungus to overwinter in its host.[16] In 1915, William Murrill reported the sclerotia of C. tuberosa to be bioluminescent.[17]

The spore print is white.[18] Individual spores are smooth, ellipsoid to tear-shaped in profile, obovoid to ellipsoid or cylindric in face or back view, with dimensions of 4.2–6.2 by 2.8–3.5μm. They are inamyloid and acyanophilous (non-reactive to staining with Melzer's reagent and Methyl blue, respectively). The basidia (spore-bearing cells in the hymenium) are club-shaped to cylindric and 15.4–21 by 3.5–5 μm. The cheilocystidia (cystidia on the gill edge) are scattered to infrequent, inconspicuous, and 17.5–31.5 μm long. Their shape ranges from a contorted cylinder to roughly club-shaped to irregularly diverticulate (with short offshoots approximately at right angles to the main stem). There are no pleurocystidia (cystidia on the gill face). The gill tissue is made of interwoven hyphae that are non-reactive to Melzer's reagent. These hyphae are smooth and thin-walled, measuring 2.8–6.4 μm in diameter. The cap tissue is made of hyphae that is interwoven below the center of the cap, radially oriented over the gills, and inamyloid. These hyphae are smooth, thin-walled, and 2.8–7 μm in diameter. The cap cuticle is a thin layer of smooth thin-walled hyphae that are more or less radially oriented, bent-over, cylindric and somewhat gelatinous, measuring 2–5 μm in diameter; they are occasionally diverticulate. The cuticle of the stem is made of a layer of parallel, vertically oriented smooth, thin-walled hyphae that are 2–4.2 μm in diameter, pale yellowish brown in alkali mounting solution. The stem has moderately thin-walled and smooth cystidia that are resemble flexuous or contorted cylinders. They are hyaline in alkali, and 3.5–7 μm in diameter. Clamp connections are present in the hyphae of all tissues.[13]

Similar species

Baeospora myosura is similar in size and appearance to C. tuberosa, but grows on spruce and Douglas-fir cones.[19] The "Magnolia coincap" (Strobilurus conigenoides) is smaller and grows on the cones of Magnolias.[12] The two remaining Collybia species closely resemble C. tuberosa, but can be distinguished by examining the stem bases at the point of attachment into the substrate. C. cookei has roughly spherical, light brown to yellowish sclerotia, while C. cirrhata does not produce sclerotia.[13] In the field, C. tuberosa may be distinguished from C. cookei by its dark reddish-brown sclerotia that somewhat resembles an appleseed.[18] A microscope provides a more definitive way of distinguishing the two: the hyphae in the sclerotia of C. cookei are rounded, while those of C. tuberosa are elongated; this diagnostic character is apparent with both fresh and dried material of the two species.[20] In contrast, C. cirrhata does not produce sclerotia.[21]

Habitat and distribution

It is not known if C. tuberosa is strictly parasitic, and needs the host to be living, or whether it is saprobic.[16] Either way, the fruit bodies of the fungus are found growing solitarily or in dense clusters on the decomposing, often blackened remains of other mushrooms. Hosts include agarics (particularly Lactarius and Russula),[18] boletes, hydnums, and polypores.[13] In the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, Russula crassotunicata is a common and abundant species that has been definitively identified as a host of both C. tuberosa and Dendrocollybia racemosa. The Russula fruit bodies are slow to decay, and are available nearly year-round as a substrate for the saprobes. Based on field observations, the authors suggest that C. tuberosa may produce fruit bodies on less decayed mushrooms, while D. racemosa produces them on much more heavily decayed mushrooms.[9]

Collybia tuberosa is found in Europe and North America,[11] and in most common in the summer and autumn, coinciding with the fruiting periods of other mushrooms.[22] It has also been reported from Japan.[23]

References

- "Collybia tuberosa (Bull.) P. Kumm. 1871". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- Hughes KW, Petersen RH, Johnson JE, Moncalvo J-E, Vilgalys R, Redhead SA, Thomas T, McGhee LL (2001). "Infragenic phylogeny of Collybia s. str. based on sequences of ribosomal ITS and LSU regions". Mycological Research. 105 (2): 164–72. doi:10.1017/S0953756200003415.

- Bulliard JBF. (1786). Herbier de la France. 6. Paris: Chez l'auteur, Didot, Debure, Belin. p. plate 256.

- Persoon CH. (1799). Observationes Mycologicae. 2. Germany, Leipzig: Gesnerus, Usterius & Wolfius. p. 53.

- Gray SF. (1821). A Natural Arrangement of British Plants. London: Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. p. 611.

- Kummer P. (1871). Der Führer in die Pilzkunde (in German) (1st ed.). Zerbst, Germany: Luppe. p. 116.

- Lennox JW. (1979). "Collybioid genera in the Pacific Northwest". Mycotaxon. 9 (1): 117–231.

- Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford, UK: CABI. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- Machniki N, Wright LL, Allen A, Robertson CP, Meyer C, Birkebak JM, Ammirati JF (2006). "Russula crassotunicata identified as a host for Dendrocollybia racemosa" (PDF). Pacific Northwest Fungi. 1 (9): 1–7. doi:10.2509/pnwf.2006.001.009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- Roosa DM, Runkel ST (2009). Wildflowers of the Tallgrass Prairie: The Upper Midwest (Bur Oak Guide). Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press. p. 183. ISBN 1-58729-796-5.

- Phillips R. "Collybia tuberosa". Rogers Mushrooms. Archived from the original on 2011-11-07. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- McKnight VB, McKnight KH (1987). A Field Guide to Mushrooms: North America. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. p. 151. ISBN 0-395-91090-0.

- Halling RE. (14 July 2009). "Collybia sensu stricto". A revision of Collybia s.l. in the northeastern United States & adjacent Canada. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- Phillips, Roger (2010) [2005]. Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: a Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- Volk T. (June 2004). "Collybia tuberosa, the mushroom-loving Collybia". Fungus of the Month. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Murrill WA. (1915). "Luminescence in the fungi". Mycologia. 7 (3): 131–33. doi:10.2307/3753180. JSTOR 3753180. (subscription required)

- Kuo M. (September 2004). "Collybia tuberosa". MushroomExpert.Com. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- Ammirati J, Trudell S (2009). Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest: Timber Press Field Guide (Timber Press Field Guides). Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 116, 121–22. ISBN 0-88192-935-2.

- Komorowska H. (2000). "A new diagnostic character for the genus Collybia (Agaricales)". Mycotaxon. 75: 343–46.

- Bessette AE, Roody WC, Bessette AR (2007). Mushrooms of the Southeastern United States. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8156-3112-5.

- Miller HR, Miller OK (2006). North American Mushrooms: a Field Guide to Edible and Inedible Fungi. Guilford, Connecticut: Falcon Guide. p. 136. ISBN 0-7627-3109-5.

- Ito S. (1959). Mycological Flora of Japan. 2. Tokyo: Yokendo Ltd.