Atholville, New Brunswick

Atholville (2016 population: 3,570[3]) is a village in Restigouche County, New Brunswick, Canada.[4]

Atholville | |

|---|---|

View of Sugarloaf from Atholville | |

Seal | |

Atholville Location of Atholville in New Brunswick | |

| Coordinates: 47.989444°N 66.7125°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Restigouche |

| Parish | Addington |

| Village Status | 1966 |

| Electoral Districts Federal | Madawaska—Restigouche |

| Provincial | Restigouche West |

| Government | |

| • Type | Village Council |

| • Mayor | Michel Soucy |

| • Deputy Mayor | Jean-Guy Levesque |

| • Councillors[2] | List of Members

|

| • MP | René Arseneault (Lib.) |

| • MLA | Gilles LePage (Lib.) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 119.60 km2 (46.18 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[3] | |

| • Total | 3,570 |

| • Density | 29.8/km2 (77/sq mi) |

| • Dwellings | 1,584 |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-3 (ADT) |

| Postal code(s) | E3N

|

| Area code(s) | 506 |

| Access Routes | |

| Median Income* | $54,128 CDN |

| Website | www.atholville.net |

| |

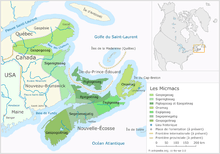

The first inhabitants of the area were the Mi'kmaq who settled there in the 6th century BC and were then called Tjikog. With 400 people, it was their biggest village and the only one permanently inhabited in the region. The Acadians arrived in 1750. It was at this time that the Mi'kmaq left the area and went to Listuguj in Quebec. The French defeat at the Battle of Restigouche on July 8, 1760 was damaging to the development of the settlement. The Intercolonial Railway, however, was inaugurated in 1876 and Anglophone merchants developed the forestry industry in the early 20th century. The village then experienced significant growth and was incorporated as a municipality in 1966. A shopping centre frequented by people from the whole region was established there from 1974. The forestry industry still plays an important role in the local economy.

Atholville's population is mostly Acadian but there is also a substantial anglophone minority. The village has several community services and facilities, including Sugarloaf Provincial Park.

Geography

Related article: Geography of New Brunswick

Location

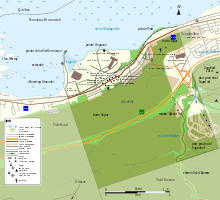

Atholville is located four kilometres west of downtown Campbellton. The village, although a francophone community of the Atlantic provinces of Canada, is generally considered part of Acadia.[5] Atholville is bordered to the north by the Restigouche River and has an area of 119.60 square kilometres, after an annexation that took place in 2015.[3] Apart from Campbellton, the village is adjacent to Val-d'Amours to the south and Tide Head to the west. The Quebec side extends, from west to east, from Restigouche-Partie-Sud-Est to Pointe-à-la-Croix and Listuguj.

Walker Creek rises in the south-east of the territory. It has a few tributaries in the area with the main one continuing east parallel to Highway 11. Walker Creek flows into the Restigouche River in Campbellton. There are also a few streams flowing directly into the Restigouche River. The site of the stockade (Booming Grounds) is a salt marsh.[6] The Appalachian Mountains cover most of the territory of the municipality. Butte Sugar, with a height of about 200 m, also extends into the territory of Tide Head and lies directly south of the built-up area of the town. South of Butte Sugar there is a valley and another mountain which extends into Val-d'Amours and Tide Head, whose height exceeds 230 metres in the Atholville portion. Only a small part of the west side of Sugarloaf (281 m) is included in the territory of Atholville.

New Brunswick Route 11 passes through the centre of the municipality south of the town from east to west: this road goes from Quebec in the west to Shediac in the southeast. The Val-D'Amour Road (Road 270) provides access from the village to Route 11. The village itself is crossed from east to west by New Brunswick Route 134 which provides access to Tide Head and Campbellton: this road is called Notre-Dame Street in the village. Val-d'Amour Road continues south to Val-d'Amour. The New Brunswick East Coast Railway, the former Intercolonial Railway, passes through the village from east to west, north of Notre-Dame Street. The river is navigable but the nearest port is Dalhousie. Campbellton railway station and Charlo Airport complete the means of transport in the region. There are taxis in Campbellton. The Cormier taxi connects Montreal to the Acadian Peninsula and has a stop in the village.

In 2015, the province of New Brunswick issued regulations that expanded the boundaries of Atholville by annexation of the service district of St. Arthur, the local service district of Val D’Amours, a portion of the Village of Tide Head and a portion of the local service district of Blair Athol. The effective date of the order was July 1, 2015.[7] The land area of the village grew from 10.25 km2 to 119.60 km2, according to census data.[8][3]

Geology

The geological base of Atholville is composed of several rock types. North of Notre-Dame Street in the lowest area there are Clastic rocks from the Campbellton formation.[9] Between this street and Highway 11 are Felsic rocks from the Dalhousie group.[9] Both types of rocks are Lower Devonian (394 to 418 million years old).[9] South of Highway 11 rather there are carbonates and evaporites from the Chaleur formation dating from the Upper Silurian period (418-424 million years ago).[9]

Environment

The Booming Grounds on the border with Tide Head is an area coming under the Joint Plan of Eastern Habitats.[10] They are home to migratory aquatic birds and breeding grounds for birds such as the Great blue heron, the Osprey, and various mammals. In addition, up to 2,000 snow geese can be observed between mid-April and late May.[11] There are many rare plants growing here including the western waterweed, the jonc délié, and the Sanicula gregaria.[10] Fourteen species of fish have been recorded in the river, the most common being the Atlantic salmon and the Slimy sculpin.[12]

Although considered a threatened species, the wood turtle is common in the region.[10] Despite the imposition of environmental controls, the AV Cell works emitted sulphur dioxide and ash into the atmosphere in 2007 several times for which they were fined in 2009.[13][14]

Housing

According to Statistics Canada the village had 1,584 private dwellings in 2016 including 1,539 occupied by residents.[3]

Toponymy

The village originally had the name Tjikog[15] but the spellings Tjigog[16] Jugugw, Tchigouk,[17] and Tzigog[18] also exist. Tjikog means "a place of superior men" in Mi'kmaq.

According to oral tradition in 1639 the village was renamed Listo Gotj by Chief Tonel.[17] The exact meaning of the place name is unknown although Father Pacifique de Valigny suggested the meaning "disobey your father!".[16] There are many other translations: "a river dividing like a hand", "a fun place in spring", "river of the long war", "small forest", "small tree", "theatre of the great squirrel quarrel", "good river for canoeing", "beautiful river like five fingers", "five branches", or "many branches".[16] In 1642 Barthélemy Vimont was the first to make a written record of the name Restigouche in reference to Chaleur Bay.[16] In 1672 Nicolas Denys was the first to mention the use of the name in connection with the village, in his Geographical and historical description of the coasts of North America, with the natural history of this country.[19] According to Father Pacifique the names Listuguj and Ristigouche or Restigouche[Note 1] derived from Listo Gotj.[16][17] Moreover, the toponym Restigouche applies, especially in a historical context, to all the settlements along the river.[20]

The village was called Sainte-Anne-de-Restigouche in the 17th century.[21][22] This name applied to the Listuguj Catholic mission in the early 20th century.[16]

The entrepreneur Robert Ferguson (1768-1851) arrived in the area in 1796 from Logierait near Blair Atholl in Scotland and built a house called Athol House: this was actually one of many Scottish names in the North of the County.[23] Robert Ferguson was nicknamed the "father and founder of Restigouche".[23] There is a village called Blair Athol 18 km by road south-east of Atholville,[23] while Point Ferguson in Atholville is named after him.[24]

At the beginning of the 20th century the village was known under four names at the same time: Soiot Athol, Shives Athol, Athol House, and Ferguson Manor.[25] One post office had Ferguson Manor on its door from 1916 to 1923 and another had Shives Athol from 1907 to 1931.[26] Following a petition the village was officially named Atholville in June 1922.[25] The Ferguson Manor post office was renamed Atholville in the following year.[26]

History

Related articles: History of New Brunswick and History of the Acadians.

Prehistory

Covered with ice during the Wisconsin glaciation, the Atholville district was probably released from the glaciers in about 13,000 BC.[27] The Goldthwait Sea subsequently covered the coastal area,[27] then gradually receded until around 8,000 BC. due to Post-glacial rebound.

The village Tjikog has been permanently inhabited since at least the 6th century BC. by the Mi'kmaqs.[15] Tjikog was fortified by a piled wall and also had a cemetery.[17] Tjikog was located in the district of Gespegeoag which included the coastline of Chaleur Bay:[28] it was the only permanently inhabited village in the whole district.[17] Before the arrival of Europeans the village had a population of between 400 and 500,[17] making Tjikog the largest Mi'kmaq village.[22] Mi'kmaq lifestyle was based on hunting seals and birds, fishing with harpoons, and collecting shellfish. The population lived along the river nearly all year.[15] The emblem of Tjikog is the salmon.[28]

The French period

In July 1534 Jacques Cartier entered Chaleur Bay up to the mouth of the Restigouche River.[29] The French founded Acadia in 1604. Father Sebastian, a Recollect, was the first missionary to visit Tjikog in 1619 and he found a cross planted in front of a "hut of prayer".[30] The Capuchins replaced the Recollects in 1624 and the Jesuits followed in the same year then the Recollects returned in 1661.[31] The efforts of missionaries were initially focused on Cape Breton Island - where the capital of the Mi'kmaq was - then moved to Tjikog, which was regarded as the centre of Saint Anne worship in Mi'kmaq and Acadia.[22] In 1642 Father André Richard lived in the village for six months.[21] Chief Nepsuget was baptised in 1644 then 40 others in 1647.[30] Increasingly frequent contacts with Europeans allowed the Mi'kmaqs to acquire things, especially those made from metal, in exchange for furs.[32] However, diseases brought in by Europeans decimated much of the population from the 17th century.[32]

Gespegeoag was first claimed by the Iroquois and then later only by the Mohawks.[28] Oral tradition maintains, however, that in 1639 at the beginning of the Beaver Wars, a group of Mohawks from Kahnawake met Mi'kmaq fishermen in Long Island[Note 2] and, despite the warnings of his father, the son of the Mohawk Chief massacred the Mi'kmaqs sparing none but Chief Tonel.[Note 3][17] After his recovery Chief Tonel went to Kahnawake. Before executing the leaders of the attack, he exclaimed: Gotj Listo! meaning "disobey your father!".[17] From this the village was renamed Listo Gotj on his return.[17] Nicolas Denys established a store at Listo Gotj in 1647[21] but had to abandon it in 1650.[31][33] Richard Denys, the son of Nicolas, obtained control of the land on the departure of his father to France in 1671.[34] The missionary Chrétien Le Clercq lived in Listo Gotj in 1676[35] where he wrote his main texts on the Mi'kmaqs.[22] Richard found a new occupation at Listo Gotj in 1679 or 1680 fishing and drying fish as well as the fur trade.[31] In 1685 he gave land to the Recollects to open a mission.[31][36] In 1688 there was a total of 17 Europeans living at Listo Gotj[31] including 8 employees of Richard Denys.[34] The French then maintained a trading post probably on the coast of Canada (New France).[Note 4][37]

The Denys family did not meet the conditions of their concession and it became crown land.[31] The Lordship of Restigouche, 12 leagues long and 10 leagues wide,[Note 5] was given to Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville in 1690.[38] The Recollect concession was also revoked in 1690.[34] Richard Denys bought the lordship in 1691[31] but died in the same year.[34] Françoise Cailleteau, the widow of Denys, then married Pierre Ray-Gaillard and settled in Quebec. They rented part of the lordship[31] but the area became abandoned and, apart from the Micmacs, there was no more than one Frenchman, one Canadian, and some half-caste children at Listo Gotj in 1724.[31] The United Kingdom obtained control of Acadia in 1713 through the Treaty of Utrecht. The treaty was vague: the French thought they retained the territory now corresponding to New Brunswick while the British believed they had control. The Mi'kmaq left Listo Gotj for Listuguj on the north bank of the river in Quebec. Several sources place this event in 1745[16][39] while others mention 1759[40] and even 1770.[20] The decision by the Mi'kmaq was related to the intrusion of Europeans into the heart of their village[15] and their desire to move the Mi'kmaqs from a Protestant colony to a Catholic colony[20] or rather to ensure that they remained faithful to the King of France.[39]

.jpg)

The Acadians settled in Pointe-aux-Sauvages on the present site of Campbellton between 1750 and 1755 - the year of the start of the Expulsion of the Acadians.[21] In 1753 the daughter of Françoise Cailleteau sold the lordship of Restigouche to one Bonfils from Quebec.[31] In 1759, after the fall of Quebec, the colony begged France to send reinforcements.[41] On 19 April 1760 six ships, under the command of François Chenard de la Giraudais, left Bordeaux carrying 400 men and food.[41] Giraudais, on learning that a British fleet had penetrated into the Saint Lawrence River, decided to take refuge in the Restigouche River and set up batteries on its banks.[41] The Battle of Restigouche took place east of the village from 3 to 8 July 1760. The British fleet outnumbered the French.[21] Without reinforcements, Montreal surrendered on 8 September to the troops of Jeffery Amherst. The French troops at Restigouche surrendered on 23 October and were repatriated to France. The United Kingdom officially took possession of New France in 1763 by signing the Treaty of Paris. In 1764 Bonfils tried to gain recognition of his ownership of the lordship of Restigouche but it was refused under an Act of 1759 canceling all the concessions made under the French regime.[31]

Under British rule until the constitution

After the French and Indian War British traders established pickling plants for salmon.[15] Meanwhile, George Walker, from Bathurst, established a branch of his business in Walker Creek in 1768, on the site of Campbellton.[37] Hugh Baillie obtained the first concession which he sold to Englishman John Shoolbred.[37] Colonization was not, however, a priority and Shoolbred, not having built a school or street, lost his concession to an employee.[37]

The Loyalists arrived in New Brunswick from 1783 but did not get concessions in the county.[38] The Listo Gotj concession was granted to Samuel Lee in 1788 and since then the village became more developed than Campbellton.[37] Samuel Lee also opened a sawmill at Walker Creek which was the first step towards the directing of the economy to logging.[37] The Scotsman Robert Ferguson arrived in the area in 1796 and inherited the business of his brother Alexander.[42] His thriving business contributed to the immigration of other Scots to the region.[43] A chapel was built in 1810 in the old cemetery: it closed its doors in 1834.[44] Around 1812 Robert Ferguson built boats at Listo Gotj.[42] Part of the fleet, which had Ferguson aboard, was captured by American pirates during the War of 1812.[42] After leaving his confinement Robert Ferguson built a store and a house named Athol House[42] from which the village derives its modern name of Atholville.[23] The 1825 Miramichi Fire destroyed much of the New Brunswick forests.[15] The logging industry then moved northward and sawmills and shipyards were opened in Atholville and also in Campbellton[15] from 1828.[37] Meanwhile, in 1826 Atholville and several other places in the area were grouped into Addington Parish in Gloucester County from a portion of Beresford Parish.[Note 6][45] Restigouche County, comprising the parishes of Addington and Eldon was separated from Gloucester County in 1837.[45]

Robert Ferguson was granted the concession for the territory in 1850.[21] A school was opened at that time on Roseberry Street in Campbellton which served Atholville. This building sparked the development of the urban area towards Atholville in the west.[37] The stocks of quality trees were exhausted in 1855 but fish canning and shingle factories opened.[37] The Intercolonial Railway passed through the village in 1876 which represented a significant economic opportunity.[15] Athol House was used as a weather station[46] but was destroyed in a fire in 1894.[26] The Shives company inaugurated the largest shingle works in the Maritime Provinces in 1901.[18] The Mowatt and WH Miller mills became operational in 1902 and 1905 respectively.[21] The first school was founded in 1905.[21] The post office was founded in 1906.[47] The church opened in 1909 - Atholville was then a mission of Campbellton.[18] The parish of Our Lady of Lourdes was set up in 1913.[48] The construction of the Fraser mill by the Restigouche Company began in 1919.[21] The plant was inaugurated in 1928[49] and became the third largest paper producer in the north of the province in 1929.[50] Atholville high school opened its doors in 1930.[21] The Daughters of Mary of the Assumption settled in 1934.[18] The credit union was founded in 1938.[51] The local improvement committee was founded in 1947.[21] A waterworks and sewer were inaugurated in 1950.[21] The Versant-Nord school was inaugurated in 1951[52] in the same year as the fire station.[21] The Brothers of the Sacred Heart settled in the village in 1956.[18] The J. C. Van Horne Bridge was inaugurated in 1961 in Campbellton which enabled faster travel to Quebec and contributed much to the economy.[37] Radio Engineering Products opened a factory around 1963.[18]

From the Constitution to the present day

On 9 November 1966 the Municipality of the County of Restigouche was dissolved[53] and Atholville was incorporated as a village.[54] The rest of Addington Parish became a Local service district in 1967.[53] The municipal library opened its doors in the same year.[21] A merger of Atholville with Richardsville and Campbellton was studied in 1971.[55] but only the latter two were merged. Mayor Raymond Lagacé, who was elected in the same year, was one of the main opponents of municipal mergers.[56] The Sugarloaf Provincial Park was opened for winter sports in 1971 and officially opened the following year.[21] The province then saw a "golden age" of tourist development.[57] The Restigouche Centre, a shopping centre, was built in 1974.[21] A Community pool, offered by the Royal Canadian Legion, opened in 1975.[21] Residential development in Saint-Louis street started in 1976.[21] The Royal Canadian Legion got a new hall in 1977.[21] The Fraser factory in Atholville and the NBIP Dalhousie plant each received $30 million in 1980 for modernization works.[58] In total $170 million was invested in Atholville to convert the plant processes from bisulphate to magnesium.[59]

The Northeast Pine company, a furniture manufacturer, closed its plant in the early 1980s[60] and the municipality obtained ownership of the plant in 1987 to create an industrial mall.[60] The paper industry was in crisis in the same year and Fraser separated the Atholville mill into an independent company: Atholville Pulp. The factory achieved profit in subsequent years.[59] In 1988 the Atholville industrial park was the most used in the north of the province.[60] The Atholville Pulp plant however closed in 1991.[59] A pumping station was built in 1993.[21] The Fraser company sold the Atholville Pulp factory to Repap in 1994. Repap wanted to produce methanol but market conditions forced it to abandon its plans and to close the plant in 1996 after producing pulp for only six months.[59] Atholville Manor opened in 1998.[21] The Fils Atlantique textile spinning mill (Atlantic Yarns) opened in the industry mall in the late 1990s.[61]

Miller Brae park was inaugurated in 2000.[21] A new public library was built in 2002.[21] A new reservoir was installed in 2005.[21] Fills Atlantique closed for 10 months in 2008 mainly because of the global recession and large debts.[61] A recovery plan was accepted during the same year but the company finally declared bankruptcy in 2009.[61] The Atholville Credit Union merged with the Campbellton, Balmoral, Val-d'Amour, Charlo, Eel River Crossing, and Kedgwick Credit Unions in 2009 to form the Restigouche Credit Union.[62] From October 2010 to January 2012 the Versant-Nord school has some students from the Roland-Pépin Universal school in Campbellton during some emergency work being done on their school as the structure was dangerous.[63] Mayor Raymond Lagacé retired from municipal politics in 2012 after 43 years, including 41 at the town hall: he was the longest-serving mayor in New Brunswick.[56] The disused textile mill was purchased in 2014 by the Zenabis company to produce medical marijuana.[64]

Administration

City Council

The council consists of a mayor and five councillors.[54] The current council was elected at the quadrennial election of 14 May 2012.[54]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The municipality has six to eight employees on average, plus seasonal employees.[21]

Budget and Taxation

The annual expenditure of Atholville village amounted to 2,936,943 dollars in 2011. Of this amount:[65]

- 18.4% was spent on administration,

- 7.5% on town planning,

- 7.2% on the police,

- 6.3% on protection against fire,

- 7.1% on the distribution of water,

- 0.2% on emergency services,

- 0.1% on other protection services,

- 22.6% on transport,

- 4.1% on sanitation,

- 0.0% on public health,

- 7.2% on management,

- 12.4% on recreation and culture,

- 12.7% on debt costs, and

- 1.7% on signage

Regional services commission

Atholville is part of Region 2,[66] a regional services commission (CSR) which officially started operations on 1 January 2013.[67] Atholville is represented on the council by the Mayor.[68] Mandatory services offered by the CSR are: regional planning, management of solid waste, emergency planning measures, and collaboration on police, planning, and cost sharing of regional infrastructure for sport, recreation and culture. Other services could be added to this list.[69]

Representation and political trends

Related articles: Politics of Canada and Politics of New Brunswick.

In New Brunswick Atholville is part of the provincial electoral district of Campbellton-Restigouche Centre which is represented in the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick by Greg Davis of the Progressive Conservative Party of New Brunswick. He was elected in 2010. For the Canadian Federal Parliament, Atholville is part of the federal electoral district of Madawaska-Restigouche which is represented in the House of Commons of Canada by Bernard Valcourt of the Conservative Party of Canada. He was elected at the 41st general election in 2011.

Atholville is a member of the Union of Municipalities of New Brunswick and the Francophone Association of Municipalities of New Brunswick.[21]

Demographics

Population

| Canada census – Atholville, New Brunswick community profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | |

| Population: | 3,570 (-5.5% from 2011) | 1,237 (-6.1% from 2006) | 1,317 (-4.6% from 2001) |

| Land area: | 119.60 km2 (46.18 sq mi) | 10.25 km2 (3.96 sq mi) | 10.25 km2 (3.96 sq mi) |

| Population density: | 29.8/km2 (77/sq mi) | 120.7/km2 (313/sq mi) | 128.5/km2 (333/sq mi) |

| Median age: | 50.3 (M: 50.5, F: 49.9) | 49.9 (M: 49.1, F: 51.2) | 47.0 (M: 45.7, F: 48.2) |

| Total private dwellings: | 1,584 | 588 | 576 |

| Median household income: | $54,128 | $43,469 | $39,625 |

| References: 2016[70] 2011[71] 2006[72] earlier[73] | |||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [74][8][3] 2011 population was revised due to boundary changes after 2015 annexation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Language

| Canada Census Mother Tongue - Atholville, New Brunswick[74] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Total | French |

English |

French & English |

Other | |||||||||||||

| Year | Responses | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | |||||

2016 |

3,540 |

3,095 | 87.4% | 375 | 10.6% | 60 | 1.7% | 10 | 0.3% | |||||||||

2011 |

1,225 |

920 | 75.10% | 255 | 20.82% | 40 | 3.26% | 10 | 0.82% | |||||||||

2006 |

1,270 |

905 | 71.26% | 305 | 24.01% | 50 | 3.94% | 10 | 0.79% | |||||||||

2001 |

1,340 |

1,095 | 81.72% | 220 | 16.42% | 0 | 0.00% | 25 | 1.86% | |||||||||

1996 |

1,380 |

1,120 | n/a | 81.16% | 235 | n/a | 17.03% | 25 | n/a | 1.81% | 0 | n/a | 0.00% | |||||

Economy

Employment and income

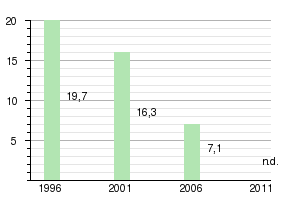

The 2006 Census by Statistics Canada also provided data on the economy. For people over 15 years old the Labour force rate was then 63.1%, the Employment-to-population ratio was 59.0%, and the unemployment rate was 7.1%. For comparison, those for the whole province were respectively 63.7%, 57.3% and 10.0%.[75]

Nearly 1,500 people work in Atholville which is more than the total population of the village.[21]

Evolution of unemployment in Atholville

- Sources

- Profiles of communities in 1996 - Atholville - Income and Work, Statistics Canada website

- Profiles of communities in 2001 - Atholville - Work, Statistics Canada website

- Profiles of communities of 2006 - Atholville - Work, Statistics Canada website

Of those aged 15 years and over, 785 people reported profits and 1,085 reported income in 2005.[76] 86.5% also reported hours of unpaid work.[75] The median income then stood at $20,393 before tax and $18,692 after tax compared to the provincial average of $22,000 before tax and $20,063 after tax. Women earned on average $8,330 less than men after tax with an average income of $15,533.[76] On average 72.3% of income came from earnings, 21.1% from government benefits, and 6.4% from other sources.[76] 6.3% of all households were below the Poverty threshold after tax which increased to 7.8% for those under 18 years old.[76]

Among the working population, 2.3% of people worked at home, none worked outside the country, 5.3% had no fixed place of work, and 92.4% had a fixed place of work.[77] Of workers with a fixed place of work, 37.2% worked in the village, 57.9% worked elsewhere in the county, 1.7% worked in another county, and 3.3% worked in another province.[77]

Main Economic sectors

1.4% of jobs were in the agricultural, fisheries and other resources sector, 4.3% were in Construction, 10.7% in manufacturing, 1.4% in wholesale, 21.4% in retail, 1.4% in finance and real estate, 17.1% in health and social services, 7.1% in education, 4.3% in trade services, and 30.0% in other services.[75]

The AV Cell Inc. factory, owned by the Aditya Birla Group, produces chemical pulp for Viscose factories in Asia. It has more than 280 employees.[78] The industrial mall houses six industrial companies with a total of one hundred employees in 2011.[79] Atholville has several other large employers, such as manufacturers of playground equipment, tyres, wood panelling, toys, and windows, as well as a bakery.

The Restigouche Centre is the main commercial centre of the region.[21] The village has several other shops including three car dealerships and a grocery store.[21] Many other products and services are available in Campbellton which has, among others, financial institutions and a NB Liquor store. Enterprise Restigouche is responsible for economic development.[80]

- The Av Cell factory.

- The Industrial Mall.

- Shops on Val-d'Amour road.

- The Credit Union.

Local Life

Education

Versant-Nord school teaches children from kindergarten to 8th year. It is a French public school within sub-district 1 of the Francophone Nord-Est School District.[52] Campbellton also has the Community College of New Brunswick (CCNB) of Campbellton which is also French language while the closest English-speaking community college is the New Brunswick Community College (NBCC) at Miramichi. The nearest francophone university campus is that of the Université de Moncton in Edmundston. Fredericton has several English language universities. A library service is also available.

For over 15 years 42.8% of the population had no certificate, diploma or degree, 22.1% had only a diploma of secondary education or equivalent, and 34.7% of them also held a certificate, diploma or a post-secondary degree. By comparison the rates were 29.4%, 26.0% and 44.6% respectively for the province.[81] In the same age group 9.0% had graduated from a short NBCC program or equivalent, 15.8% had graduated from a long program at NBCC or equivalent, 1.8% had a diploma or a university certificate below a bachelor's degree, and 8.1% had a certificate, diploma or higher degree.[81] From the graduates, 6.4% were trained in education, 2.6% in humanities, 3.8% in social sciences or law, 29.5% in commerce, management or administration, 2.6% science and technology, 15.4% in architecture, engineering or related areas, 2.6% in agriculture, natural resources and conservation, 28.2% in health, parks, recreation and fitness, and 10.3% in personal services, protection or transportation. There were no graduates in arts or communications, mathematics or computer science, nor in areas classified as "other".[81] Post-secondary graduates completed their studies outside the country in 5.1% of cases.[81]

Health and Safety

Atholville, Campbellton, and Tide Head cooperate in emergency measures.[21] Atholville bought the 911 emergency service from Campbellton.[21] The nearest detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police is in Campbellton.

Campbellton has the French-speaking Restigouche Hospital Centre and the English-speaking Campbellton Regional Hospital. New Brunswick hospitals are bilingual overall but unilingual in their jurisdictions. Campbellton also has an Ambulance New Brunswick station.

Infrastructure and communications

The village is connected to the NB Power network and also has an industrial-sized generator at the Town Hall.[21] Atholville has a water and sewerage network with a sewerage treatment plant.[21] The village of Val-d'Amour is connected to the Atholville water system.[21] Atholville also has an agreement with Campbellton and Tide Head for water supply.[21]

Many publications are available but French-speakers have primarily the daily L'Acadie Nouvelle, published in Caraquet, and the weekly L'Étoile, published in Dieppe. There is also the weekly L'Aviron published in Campbellton. English-speakers in turn have the daily Telegraph-Journal, published in Saint John, and the weekly Campbellton Tribune. There is no television station in the region but Radio-Canada Acadie (CBAFT-DT), Ici RDI, Rogers TV, and CHAU-DT are the main French television networks. The main French radio stations are the Ici Radio-Canada Première and CIMS-FM from Balmoral. English-speakers have CBC Television, CBC News Network, Global Television Network, and CTV Television Network. English radio stations include CBC Radio and CKNB in Campbellton.

Atholville has a post office. The population also has access to the cell phone network and high-speed internet. The main provider is Bell Aliant. The nearest offices of Service New Brunswick and Service Canada are in Campbellton.

Religion

Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes is a Roman Catholic church which is part of the Diocese of Bathurst. The priest is Father Claude Benoit.[48] There is also a gospel chapel. The region is part of the Anglican Diocese of Fredericton and Campbellton has several other places of worship for Protestants. The parish cemetery is located between the church and Saint-Louis street.

Sports

The village has two football fields, a skating rink, a public pool, Miller Brae Millennium Park, and the Sugarloaf Provincial Park.[21] In summer this park offers a camping area, a bicycle park, slopes for mountain biking, cycle touring, 25 kilometres of hiking trails, a picnic site, and tennis courts.[82] The park is also equipped for Geocaching.[82] In winter the park has twelve slopes for downhill skiing and snowboarding, Snowshoe trails, a naturally illuminated skating rink, and a tubular ice slope.[83]

Atholville contributes to the funding of Campbellton Civic Centre with Tide Head.[21] A trail passes through the village towards Tide Head where it joins the International Appalachian Trail. A gazebo was built at the top of the Old Mission. There are several unmarked viewing points such as that at boulevard Beauvista.

- The Ski resort on Sugarloaf

- Public pool

- The Alma Community Centre

Campbellton Civic Centre

Campbellton Civic Centre

Culture and heritage

Architecture and monuments

The buildings in the Provincial Park were designed by architect Leon R. Kentridge, from the Marshall Macklin Monaghan Limited firm of Toronto. The coverings and roof are in Shingle with a gentle slope typical of a ski resort.[57]

A War memorial is located east of the Town Hall. The old Athol House Cemetery is the oldest in Restigouche County.[44] There is a monument to the memory of Athol House Chapel.[44] It is located in the river behind the AV Cell factory.

The ruins of the landing stage that allowed the supply of wood for the pulp and paper mill until the 1960s are still visible in to the west of the Village.[84]

Languages

According to the Official Languages Act, Atholville is bilingual[85] as English and French are both spoken by more than 20% of the population. In 2011 Atholville became the third municipality in New Brunswick (after Dieppe and Petit-Rocher) to adopt an ordinance on outdoor advertising language requiring bilingual display in English and French.[86] Until then, most of the signage was in English.

An English sign photographed in 2011.

An English sign photographed in 2011. A French sign also photographed in 2011.

A French sign also photographed in 2011.

Culture

Atholville is briefly mentioned in several novels including Le Feu du mauvais temps (Fire in bad weather) (1989) by Claude Le Bouthillier. The village is also mentioned in the biographies: Ma's Cow: Growing Up in the Canadian Countryside During the Cold War (2006) by Patrick Flanagan, David Adams Richards of the Miramichi: A Biographical Introduction (2010) by Michael Anthony Tremblay and Tony Tremblay, and Think Good Thoughts (2010) by J.P. (Pat) Lynch.

The history, culture and geography of the region are featured at the Museum of the Restigouche River at Dalhousie. The National Historic site of the Battle of Restigouche at Pointe-à-la-Croix commemorates this battle.

Notable people linked to the municipality

- Lewis Charles Ayles (1927-), lawyer and politician, born in Atholville;

- Edmond Blanchard (1954-), politician, born in Atholville;

- Joseph Claude (died in 1796), Chief of Listuguj;

- Robert Ferguson (Logierait (Scotland) 1768 - Campbellton 1851), businessman, justice, judge, official and militia officer;

- Bobby Hachey (1932-2006), artist, born in Atholville;

- Samuel Lee (Concord (Massachusetts) 1756 - Shediac 1805), official, judge, businessman and politician.

See also

Bibliography

- Irene Doyle, Atholville Photo Album, Campbellton, Irene Doyle, 2006 (in French and English)

- Étienne Fallu, The Credit Union at Atholville: 1938-1988, Atholville, 1988 (in French)

- Hélène Desrosiers-Godin, The marvelous Mount Sugarloaf: collection of anecdotes and historical facts, Atholville, Anne Gauvin, 2006, 23 p. (ISBN 2980846600) (in French)

External links

Notes and references

Notes

- The spelling Ristigouche is more common in French while Restigouche is preferred in English. Listuguj is the modern Mi'kmaq name.

- Long Island is located in the Ristigouche river in Tide Head, 7 kilometres west of Atholville.

- Tonel means "thunder".

- Not to be confused with modern Canada. Canada was a province of New France corresponding roughly with Québec.

- About 46.8 km by 39 km, comprising the territory along the coast between Tide Head to the west and Belledune to the east.

- In New Brunswick, a parish is a territorial sub-division which lost administrative significance in 1966 but has always been used for census purposes.

References

- "Atholville". Government of New Brunswick. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011.

- "Atholville website". Archived from the original on 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Atholville, Village [Census subdivision], New Brunswick". Statistics Canada. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- "Atholville". New Brunswick Provincial Archives.

- Murielle K. Roy and Jean Daigle, Maritime Acadia, Centre d'études acadiennes, University of Moncton, Moncton, 1993, ISBN 2921166062, Demography and demo-linguistics in Acadia, 1871-1991, p. 141 (in French)

- Ralph W. Tiner, Field Guide to Tidal Wetland Plants of the Northeastern United States and Neighboring Canada, Vegetation of Beaches, Tidal Flats, Rocky Shores, Marshes, Swamps, and Coastal Ponds, Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2009, 459 pages, p. 424, ISBN 9781558496675.

- "Municipalities Order, NB Reg 85-6". CanLII. Section 34, "Village of Atholville": Government of New Brunswick. Retrieved September 28, 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "2011 Census Profile: Atholville, NB". Statistics Canada. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Bedrock Geology of New Brunswick, New Brunswick government, consulted on August 19, 2012 (in French)

- Zelazny (2007), opcit, p. 143-144.

- Jeffrey C. Domm, The Formac Pocketguide to New Brunswick Birds, Formac Publishing Company, 2005, 224 pages, ISBN 978-0-88780-674-2

- "Restigouche River, Hydrographic Basins of New Brunswick" (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Local government. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014., New-Brunswick government, online 2007, consulted on 29 November 2012 (in French).

- Ash from the paper mill causes discontent in Atholville, Radio-Canada News, October 17, 2012, consulted on November 27, 2012 (in French).

- The public are not reassured, Radio-Canada News, July 20, 2007, consulted on November 27, 2012 (in French).

- Vincent F. Zelazny, Our Country Heritage, The history of ecological classification of the lands of New-Brunswick, 2nd edition, Ministry of Natural Resources of New-Brunswick, Fredericton, 2007, 404 pages, p. 144–145, ISBN 978-1-55396-204-5, Read online Archived May 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, consulted on 7 August 2009 (in French)

- Listuguj, Toponymy Commission of Québec, consulted on 29 November 2012 (in French).

- The Micmacs at the Athol house Site, Restigouche Gallery website, consulted on 21 August 2012

- Margerite Michaud, The Acadians of the Maritime provinces, historical and tourist guide, Imprimerie acadienne, Moncton, 1968, 165 pages, p. 61 (in French).

- Original name: Description géographique et historique des côtes de l'Amérique septentrionale, avec l'histoire naturelle de ce pays, (in French)

- William Gagnong, A Monograph of the Origins of the Settlements in New Brunswick, J. Hope, Ottawa, 1904, 185 pages, p. 168-169

- A self-sufficient municipality...and more too Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, consulted on 8 December 2011 (in French)

- Denise Lamontagne, Religion at Sainte-Anne in Acadia, Presses de l'Université Laval, Québec, 2011, pp. 151-152, ISBN 978-2-7637-9323-8 (in French)

- William Baillie Hamilton, Place Names of Atlantic Canada, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1996, 502 pages, p. 45

- Hamilton (1996), opcit, p. 74.

- L'Évangéline, 15 June 1922, 5 pages, (in French)

- Alan Rayburn, Geographical Names of New Brunswick, Energy, Mines, and Resources Canada, Ottawa, 1975, p. 40

- General geological map of shallow sediments in New Brunswick, AA. Seaman, 2002, Ministry of Natural Resources and Energy, consulted on 7 August 2009 (in French)

- Philip K. Bock and William C. Sturtevant, Handbook of North American Indians, 13 Volumes, Vol. 1, Government Printing Office, 1978, pp. 109-110, 777 pages

- Ristigouche River, Toponymy Commission of Québec, consulted on 29 November 2012 (in French)

- Canadian Historical society of the Catholic church, Study Sessions, Société canadienne d'histoire de l'Église catholique, 1978, p. 88 (in French).

- The French at the Athol house Site Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Restigouche Gallery website, consulted on 21 August 2012

- Bock and Sturtevant (1978), opcit, p. 117.

- Denys, Nicolas, George MacBeath, 2000, Online biographical dictionary of Canada website, University of Toronto, consulted on 21 August 2012

- Denys, Richard, George MacBeath, 2000, Online biographical dictionary of Canada, University of Toronto, consulted on 21 August 2012

- Le Clercq, Chrestien, G.-M. Dumas, 2000, Online biographical dictionary of Canada, University of Toronto, consulted on 21 August 2012

- William Gagnong, A Monograph of historic sites in the province of New Brunswick, J. Hope, Ottawa, 1899, p. 300, Read online, consulted on 15 August 2012

- Visitor Guide and maps, Campbellton website, consulted on 20 August 2012

- Ganong (1899), opcit, p. 344.

- Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, Tawow, Volumes 1 to 6, Ottawa, 1970, p. 41

- Bona Arsenault, History of Acadians, Éditions Fides, Montreal, 2004, 502 pages, p. 230, ISBN 978-2-7621-2613-6 (in French)

- W.J. Eccles, Battle of Restigouche, The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Ferguson, Robert, William A. Spray, 2000, Online biographical dictionary of Canada, University of Toronto/Laval University, consulted on 29 NOvember 2012.

- Lucille H. Campey, The Scots, The Pioneer Scots of Lower Canada, 1763-1855, Dundurn, 2006, 336 pages, p. 115, ISBN 9781554882090

- Notre-Dame de Lourdes parish, Irene Doyle, 1998, Irene's genealogy and history website, consulted on 20 August 2012

- Genealogical guide to the county of Restigouche, 2006, Archives provinciales du Nouveau-Brunswick website, consulted on 24 November 2012 (in French)

- Adrian Room, Dictionary of World Place Names Derived from British Names, Taylor & Francis, 1989, 221 pages, p. 9, ISBN 9780415028110.

- Place names of New Brunswick - Atholville, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, consulted on 1 November 2011 (in French).

- Notre-Dame de Lourdes parish Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Diocese of Bathurst, consulted on 20 August 2012

- Nicolas Landry and Nicole Lang, History of Acadia, Éditions du Septentrion, Québec, 2001, p. 259 (in French).

- Donald J. Savoie and Maurice Beaudin, The struggle for development, the north-east case, Presses de l'Université du Québec/Institut canadien de recherche sur le développement régional, Sillery/Moncton, 1988, 282 pages, p. 32, ISBN 2760504808 (in French)

- Étienne Fallu, The Credit Union of Atholville, 1938-1988, Atholville, 1988 (in French)

- Francophone North-East, Ministry of Education of New Brunswick], consulted on 2 November 2012 (in French)

- Framework of local government and viable regions: plan of action for the future of local governance in New Brunswick, Jean-Guy Finn, Fredericton, November 2008, 83 pages, p. 30, ISBN 978-1-55471-181-9, Read online Archived November 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Quadrennial municipal elections Archived December 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, 14 May 2012, Report of the Director-general on the municipal elections, Read online Archived December 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, consulted on 24 December 2013

- New Brunswick. Dept. of Municipal Affairs, Ministry of the Environment and local government, Amalgamation Study For Campbellton, Atholville, and Richardsville, Fredericton, 1971, 35 pages.

- Jean-François Boisvert, The doyen of municipal politics demands respect, L'Acadie Nouvelle, 4 April 2012 (in French)

- John Leroux, Building New Brunswick, An Architectural History, Goose Lane Editions, Fredericton, 2008, p. 239, ISBN 978-0-86492-504-6.

- Savoie and Baudin (1988), opcit, p. 160.

- Graeme Rodden, Atholville Receives a New Lease on Life as Av Cell, Pulp & Paper Canada, 1 April 1999, Read online Archived 2013-12-24 at the Wayback Machine, consulted on 23 August 2012.

- Savoie and Baudin (1988), opcit, p. 96.

- Radio-Canada, The future does not have yarn, 15 January 2009, Radio-Canada News, See online, consulted on 27 November 2012 (in French).

- Restigouche Credit Union Archived August 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Acadian Credit Unions website, consulted on 30 December 2010.

- Radio-Canada, Roland-Pépin school resumes life, 26 January 2012, Radio-Canada News, See online, consulted on 23 February 2012 (in French)

- Jean-François Boisvert, Marijuana: Zenabis chooses Atholville, L'Acadie Nouvelle, 11 March 2014, Read online (in French)

- Annual report on municipal statistics for New Brunswick - 2012, Fredericton, 2012, Read online.

- The communities in each of 12 Regional Services Commissions (CSR), New Brunswick government website, consulted on 9 November 2012.

- Administration councils for Regional Services Commissions announcements, New Brunswick government, consulted on 1 November 2012.

- Governance of new Regional Services Commissions, New Brunswick government, consulted on 9 November 2012.

- Obligatory services, New Brunswick government website, consulted on 9 November 2012.

- "2016 Community Profiles". 2016 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. February 21, 2017. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- "2011 Community Profiles". 2011 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. July 5, 2013. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- "2006 Community Profiles". 2006 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. March 30, 2011. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- "2001 Community Profiles". 2001 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. February 17, 2012.

- Statistics Canada: 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 census

- Profiles of communities of 2006 - Atholville - Work, Statistics Canada website, consulted on 20 November 2012.

- Profiles of communities in 2006 - Atholville - Income and profits, Statistics Canada website, consulted on 20 November 2012.

- Profiles of communities in 2006 - Atholville - Place of work, Statistics Canada website, consulted on 20 November 2012.

- AV Cell Inc. Archived 2014-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, AV Group website, consulted on 15 June 2014.

- Renovations in the industrial mall in Atholville, New Brunswick government website, consulted on 9 November 2011

- Regional services district 2 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Foundation of local governments and viable regions (Finn Report)], on the New Brunswick government website, consulted on 25 July 2011.

- Profiles of communities in 2006 - Atholville - Education, Statistics Canada website, consulted on 20 November 2012.

- Things to do in Summer Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Sugarloaf Park website, consulted on 27 November 2012.

- Things to do in Winter Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Sugarloaf Park website, consulted on 27 November 2012.

- Brian Solomon, The Railroad Never Sleeps, 24 Hours in the Life of Modern Railroading, Voyageur Press, 2008, 176 pages, ISBN 9780760331194

- Law on Official languages (New Brunswick), 7 June 2002, Articles 35, 36, 37, and 38, Read online Archived January 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, consulted on 15 March 2011.

- Jean-François Boisvert, Bilingual Signage Obligatory, L'Acadie Nouvelle, 15 March 2011, consulted on 5 March 2011 (in French)