Tangsa Naga

The Tangsa or Tangshang Naga in India and Myanmar (Burma), is a Naga tribe native to Changlang District of Arunachal Pradesh, parts of Tinsukia District of Assam, in north-eastern India, and across the border in Sagaing Region, parts of Kachin State, Myanmar (Burma). The Tangshang in Myanmar were formerly known as Rangpang, Pangmi, and Heimi/Haimi. Tangshang/Tangsa is the largest Naga sub-tribe having an approximate population of 450,000 (India and Myanmar). Their language is called Naga-Tase in The Ethnologue and Tase Naga in the ISO code (ISO639-3:nst). They are a scheduled group under the Indian Constitution (where they are listed under ‘other Naga tribes’) and there are many sub-groups within Tangsa on both sides of the border.

Tangshang | |

|---|---|

Diorama of Tangsa people in Jawaharlal Nehru Museum, Itanagar. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Tangsa language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Animism, Rangfrah | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Naga, Nocte, Konyak |

Background

The Tangshang in Myanmar as well as the Tangsa in India regard themselves as a Naga tribe. They are well-built and of medium-stature. Today Tangsa people live in the Patkai mountains, on the border of India and Burma, and some live in the plains areas on the Indian side of the border. Many Tangsa tell of migrations from what is now Mongolia, through the South-West China Province of Yunan into Burma. Tangsa traditions suggest that they settled in the existing region from the beginning of the 13th century. It is believed that in their native place in China and Burma they were known as ‘Muwa’ and ‘Hawa’ respectively. The term ‘Hawa’ (also pronounced ‘Hewe’ or ‘Hiwi’) is used by many Tangsa to refer to the whole group of Tangsa. The term Tangsa is derived from ‘Tang’ (high land) and ‘Sa’ (son) and means 'people of the high land'.

Subgroups

There are many sub-groups of Tangsa, all of which speak distinctive linguistic varieties. Some of these varieties are very similar, and some are very different from each other. Each of these subtribes is known by a number of different names. There is the name the group gives to itself, for example Chamchang, and then a ‘general name’, used in communication with non-Tangsas. The general name for the Chamchang is Kimsing.

About 70 different subtribes have been identified;[1][2][3] Within India, the most recently arrived Tangsa are known as Pangwa.

These are listed with the name used by the group itself first, followed by alternative spellings in brackets. M indicates the group is found only in Myanmar, I only in India and B in both India and Myanmar. This list is not complete:

- Bote (Raqha, Bongtai) B

- Cyamcyang-Shecyü (Chamchang, Kimsing,Sankey) B

- Cyampang (Champhang, Thamphang) B

- Cyolim (Cholim, Tonglum) B

- Cyuyo (Chuyo, Wangku) M

- Jöngi (Dunghi) B

- Gaqha M

- Gaqya (Gahja) I

- Gaqkat (Wakka) B

- Gaqchan (Gashan) M

- Gaqlon (Galun, Lonyung) B

- Kochung M

- Kotlum (Kawlum) M

- Gaqyi M

- HaqcyengB

- Haqcyum M

- Haqkhi (Hachi) M

- Haqkhun B

- Haqman M

- Haqpo (Hatphaung, Apo) M

- Hasa (Lulum as a village name, live close to Taka village) M

- Haqsik (Awlay, Awlaw, Laju) M

- Hokuq M

- Havoi (Havi) I

- Henching (Shangcheing, Shangchaing) M

- Yoglei (Yogli, Yawklai) I

- Kaisan M

- Khalak or Khilak(Tangsa) B

- Kumkaq M

- Lakkai (Lati) B

- Kuku (Makhawngnyon) M

- Lama (Haqlang) B

- Lochang (Lanching, Lanchien) B

- Longchang I

- Lungkhi (Lungkhi, Lungkhai) B

- Lungri (Lungri) B

- Lumnu M

- Lungphi (Longphi) I

- Meitei (Mitay) B

- Miku M

- Muklom (Moklum) I

- Mossang (Tangsa) (Mawshang) B

- Mungre (Mawrang, Morang) B

- Nahen M

- Ngaimong B

- Nyinshao (Nyinshao) M

- Nukte (Nocte) I

- Pingku M

- Ponthai I

- Pongnyon (Macyam) M

- Rancyi (Rangti, Ran-kyi, Rangsi, Rasi) M

- Raqnu M

- Rasa (Rasit) M

- Rera (Ronrang) I

- Ringkhu M

- Sansik (Siknyo, Sheiknyo, Sikpo) M

- Shangti (Shangri) B

- Shangval (Shawvel, Shangwal) B

- Shokra (Shograng) M

- Toke (Tokay) M

- Cyamkok (Thamkok) M

- Tikhak I

- Vancyo (Wancho) I

- Yangnaw M

- Asen (Yasa) M

- Kon (Yawngkon) M

- Yungkuk I

Notes: Gakat people also live in India, in the Wakka village circle of Tirap district, but are grouped with the Wancho rather than with Tangsa.

Culture

The Tangsa's habitation along the Myanmar border resulted in cultural influence from neighbouring groups across the border and the adoption of Burmese dress among many tribal members.[4]

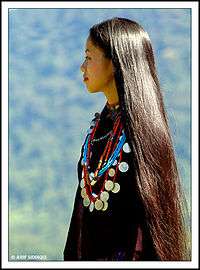

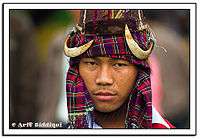

Traditionally, the Tangsa kept long hair in both sexes, which is tied into a bun and covered with a piece of cloth, known in some Tangsa varieties as the Khu-pak / Khu-phop. The menfolk traditionally used to wear a long and narrow piece of cloth called lamsam / lengti that barely covers the hip and pelvis region. However, nowadays they wear a broad cylindrical piece of cloth called lungi that is green in colour and is lined with yellow, red and white yarns, and accompanied with a sleeveless shirt. On the other hand, the costume of the womenfolk traditionally used to be a piece of cloth wrapped around the chest and a similar piece of cloth wrapped around the waist extending just below the knees. Nowadays, with the availability of yarn, their costume include an artistically woven petticoat, which acts as the lower garment, and a linen blouse.

Lifestyle

Traditionally Tangsa people practiced shifting cultivation (known as Jhwum in Assamese). Nowadays those Tangsa in the plains area of India practice wet rice cultivation. In the traditional agriculture, using simple manual tools, the Tangsa raise crops that include paddy, millet, maize and arum, and vegetables. Tangsa people make scanty use of milk and milk products, although milk tea is now served in many Tangsa houses. Traditional meals consist of a wide variety of recipes. But, staple foods are boiled or steamed rice, vegetables boiled with herbs and spices(stew) and boiled or roasted fish or meat. Snacks include boiled or roasted arum or topiaca. Traditional drinks include smoked tea(phalap) and rice beer (called ju, kham or che).[5]

Owing to the climate and terrain, the Tangsa live in stilt houses, which are divided into many rooms. Like the Nocte, the Tangsa traditionally had separate dormitories for men, known in Longchang Tangsa as Looppong for the males and Likpya for the female.

Traditionally, the Tangsa believed in a joint family system, and property is equally divided between all family members. A tribal council, known as Khaphua(Longchang), Khaphong (Muklom) was administered by a Lungwang (chief), who sees to the daily affairs of the Tangsa group.

Religion

Nowadays Tangsa follow a variety of religions. Traditionally their beliefs were animistic. One example of the animistic beliefs still practised is the Wihu Kuh festival held in some parts of Assam on 5 January each year. This involves sacrifice of chickens, pigs or buffaloes and prayers and songs to the female earth spirit, Wihu.

This group believe in a supreme being that created all existence, locally known as Rangkhothak / Rangwa / Rangfrah, although belief in other deities and spirits is maintained as well. Many followers of Rangfrah celebrate an annual festival called Mol or Kuh-a-Mol (around April/May), which asks for a bumper crop. Animal sacrifice, in particular the sacrifice of 'Wak' (pigs) and 'Maan' (cows), is practised. At funerals a similar ceremony is undertaken and a feast between villagers is held by the bereaved family. After dusk, man and women start dancing together rhythmically with the accompanying drums and gongs.

Some Tangsas, particularly the Tikhak and Yongkuk in India and many Donghi in Myanmar, have come under the influence of Theravada Buddhism,[6] and have converted.[7] There are Buddhist temples in many Tikhak and Yongkuk villages.

Most of the Tangsas, including most of the Pangwa Tangsas, and nearly all of the Tangshang in Myanmar, have accepted Christianity.[8] Probably the most widespread Christian denomination in both Myanmar and India is Baptist. Tangsa Baptist Churches' Association with its headquarters at Nongtham under Kharsang sub-division is the largest Baptist Association working among the Tangsas with more than 100 churches affiliated to it[5], but there are also large numbers of Presbyterians in India, and perhaps smaller numbers of Catholics, Church of Christ and Congregationalists.

Out of a total of 20,962 Tangsa (proper) living in Arunachal Pradesh, 6,228 are Animist (29.71%) and 5,030 are Hindu (24.00%). Most of the remaining are Christian (44%), with a Buddhist minority of close to 3%. There are another 8,576 Tangsa residing in Arunachal, belonging to fringe Tangsa groups such as Mossang, Tikhak and Longchang. The Mossang, Rongrang, Morang, Yougli, Sanke, Longphi, Haisa, and Chamchang (Kimsing) tribes are mostly Christian. Most of the Longchang and Langkai are Rangfrahites, while the Tikhaks are evenly divided into Christians and Buddhists. Taisen is majority Buddhist. The Moglum Tangsa are evenly divided between Rangfrah, Animists and Christians. The Namsang Tangsa are two-thirds Animist, with the remaining one-third Hindu.[9]

Language

At present the ISO code for these speech varieties is ISO639-3:nst. The closest linguistic relatives to Tangsa are Tutsa and Nocte, and all of these, together with several other languages, make up the Konyak subgroup within a larger group sometimes called Bodo-Konyak-Jinghpaw.[10]

Tangsa is not a single language, but a network of varieties some of which are mutually intelligible and some of which are not. For example, within the Pangwa group, Longri and Cholim (Tonglum) speakers understand each other easily, but speakers of these two groups may have more difficulty understanding and speaking Lochhang (Langching).

The following table shows some of the linguistic differences between Tangsa groups:

| Gloss | Cholim | Longchang | Rera | Jugli | Tikhak | Yonguk | Muklom | Hakhun | Halang | Chamchang(Kimsing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| drinking water | kʰam² | kham | kʰam² | kham | kʰam² | kʰam² | jung | ʤu² | ʒɯ² | kham |

| river (water) | ʒo² | kham | ʒo² | jong | kʰam² | kʰam² | jung | ʤu² | ʒɯ² | |

| alcohol | cʰai¹ | jau | cʰe¹ | chol | ʒu² | ʒo² | kham | kʰam² | kʰam² | |

| heart | ədiŋ¹ | ran | rin¹ | rɤn¹ | rɤn¹ | tin | ran³ | ran¹ | ||

| egg | βɯ¹cʰi¹ | wutei | wu²tai¹ | wutai | wu¹ti¹ | wu¹ti¹ | wochih | u¹ti¹ | wɯ¹cʰi¹ | |

| sun | raŋ²xai² | rangsa | raŋ²sai¹ | rangshal | raŋ²sa¹ | raŋ²sa³ | rangshal | se¹ | se¹pʰo² | |

| blood | təgi¹ | tahei | gi¹ | hi | təɣi¹ | təhɤi¹ | tahih | hi¹ | sʰe¹ |

There seem to be three subgroups in India. The lexemes (words) for ‘drinking water’, other types of ‘water’ and ‘alcohol’ can be used as a diagnostic for three putative groups. The group shown in the middle of the table, the Tikhak subgroup (Tikhak and Yongkuk), is reasonably well established. They are people who came from Myanmar to India some hundreds of years ago and there are no Tikhak or Yongkuk speakers in Indi these days. They use kham for 'drinking water' and 'river water'.

To the left is a rather more linguistically diverse set of varieties termed Pangwa,[11] consisting mostly of groups that have arrived in India more recently and usually have related villages in Myanmar; although some like Joglei and Rera are now found only in India. They use kham for drinking water but ju for river water.

To the right are several diverse varieties, which use kham for alcohol and ju for drinking water. Moklum and Hakhun are not mutually intelligible but do share hierarchical agreement marking (marking of object as well as subject), though realised in systematically different ways. Hakhun is very similar to Nocte, which is listed by the ISO as a different language (ISO639-3:njb)

Online archiving

An on-line archive of Tangsa texts is available at the DoBeS website[12] and Tangsa texts can be read and searched at the Tai and Tibeto-Burman Languages of Assam website.[13]

References

- Stephen Morey (2011). Tangsa agreement markers. In G. Hyslop, S. Morey and M. Post (eds) North East Indian Linguistics II. Cambridge University Press India. pp. 76–103.

- Nathan Statezni and Ahkhi (2011). So near and yet so far: dialect variation and contact among the Tangshang Naga in Myanmar. Presentation given at NWAV Asia-Pacific I conference, Delhi, India, 23–26 February 2011.

- Mathew Thomas (2009). A Sociolinguistic Study of Linguistic Varieties in Changlang District of Arunachal Pradesh. PhD thesis submitted to the Centre for Advanced Study in Linguistics, Annamalai University.

- Satya Dev Jha (1986). Arunachal Pradesh, Rich Land and Poor People. Western Book Depot. p. 94.

- "A trip to hidden paradise - Arunachal festival promises a journey to the unknown". The Telegraph. 18 January 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- J. D. Baveja (1982). New Horizons of North East. Western Book Depot. p. 68.

- Shibani Roy, S. H. M. Rizvi (1990). Tribal Customary Laws of North-east India. B.R. Pub. Corp. p. 34. ISBN 81-7018-586-6.

- Bijan Mohanta (1984). Administrative Development of Arunachal Pradesh, 1875-1975. Uppal. p. 16.

- Table ST-14, Census of India 2001

- Robbins Burling (2003). The Tibeto-Burman Languages of Northeastern India. In G. Thurgood and R. LaPolla (eds.) The Sino-Tibetan Languages. Routledge. pp. 169–191.

- Jamie Saul (2005). The Naga of Burma. Orchid Press. p. 28.

- | url = http://www.mpi.nl/DoBeS

- | url = http://sealang.net/Assam

- Das Gupta, K. 1980. The Tangsa Language (a Synopsis). Shillong: North East Indian Frontier Agency.

- Morang, H.K. 2008. Tangsas – The children of Masui Singrapum. Guwahati: G.C. Nath on behalf of AANK-BAAK

- Rao, Narayan Singh. 2006. Tribal Culture, Faith, History and Literature. New Delhi: Mittal.

- Simai, Chimoy. 2008. A profile of the Tikhak Tangsa tribe of Arunachal Pradesh. New Delhi: Author’s Press.

- Vivekananda Kendra Institute of Culture. 2005. Traditional Systems of the Tangsa and the Tutsa. Guwahati: Vivekananda Kendra Institute of Culture.