Ancient technology

During the growth of the ancient civilizations, ancient technology was the result from advances in engineering in ancient times. These advances in the history of technology stimulated societies to adopt new ways of living and governance.

This article includes the advances in technology and the development of several engineering sciences in historic times before the Middle Ages, which began after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476,[1][2] the death of Justinian I in the 6th century,[3] the coming of Islam in the 7th century,[4] or the rise of Charlemagne in the 8th century.[5] For technologies developed in medieval societies, see Medieval technology and Inventions in medieval Islam.

|

|

A significant number of inventions were developed in the Islamic world; a geopolitical region that has at times extended from al-Andalus and Africa in the west to the Indian subcontinent and Malay Archipelago in the east. Many of these inventions had direct implications for Fiqh related issues.

Ancient civilizations

Africa

Technology in Africa has a history stretching to the beginning of the human species, stretching back to the first evidence of tool use by hominid ancestors in the areas of Africa where humans are believed to have evolved. Africa saw the advent of some of the earliest ironworking technology in the Aïr Mountains region of what is today Niger and the erection of some of the world's oldest monuments, pyramids and towers in Egypt, Nubia, and North Africa. In Nubia and ancient Kush, glazed quartzite and building in brick was developed to a greater extent than in Egypt. Parts of the East African Swahili Coast saw the creation of the world's oldest carbon steel creation with high-temperature blast furnaces created by the Haya people of Tanzania.

Mesopotamia

They were one of the first Bronze Age people in the world. Early on they used copper, bronze and gold, and later they used iron. Palaces were decorated with hundreds of kilograms of these very expensive metals. Also, copper, bronze, and iron were used for armor as well as for different weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, and maces.

Perhaps the most important advance made by the Mesopotamians was the invention of writing by the Sumerians. With the invention of writing came the first recorded laws called the Code of Hammurabi as well as the first major piece of literature called the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Several of the six classic simple machines were invented in Mesopotamia.[6] Mesopotamians have been credited with the invention of the wheel. The wheel and axle mechanism first appeared with the potter's wheel, invented in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) during the 5th millennium BC.[7] This led to the invention of the wheeled vehicle in Mesopotamia during the early 4th millennium BC. Depictions of wheeled wagons found on clay tablet pictographs at the Eanna district of Uruk are dated between 3700–3500 BCE.[8] The lever was used in the shadoof water-lifting device, the first crane machine, which appeared in Mesopotamia circa 3000 BC.[9] and then in ancient Egyptian technology circa 2000 BC.[10] The earliest evidence of pulleys date back to Mesopotamia in the early 2nd millennium BC.[11]

The screw, the last of the simple machines to be invented,[12] first appeared in Mesopotamia during the Neo-Assyrian period (911-609) BC.[13] According to the assyriologist Stephanie Dalley, the earliest pump was the screw pump, first used by Sennacherib, King of Assyria, for the water systems at the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and Nineveh in the 7th century BCE. This attribution, however, is disputed by the historian John Peter Oleson.[14][15]

The Mesopotamians used a sexagesimal number system with the base 60 (like we use base 10). They divided time up by 60s including a 60-second minute and a 60-minute hour, which we still use today. They also divided up the circle into 360 degrees. They had a wide knowledge of mathematics including addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, quadratic and cubic equations, and fractions. This was important in keeping track of records as well as in some of their large building projects. The Mesopotamians had formulas for figuring out the circumference and area for different geometric shapes like rectangles, circles, and triangles. Some evidence suggests that they even knew the Pythagorean Theorem long before Pythagoras wrote it down. They may have even discovered the number for pi in figuring the circumference of a circle.

Babylonian astronomy was able to follow the movements of the stars, planets, and the Moon. Application of advanced math predicted the movements of several planets. By studying the phases of the Moon, the Mesopotamians created the first calendar. It had 12 lunar months and was the predecessor for both the Jewish and Greek calendars.

Babylonian medicine used logic and recorded medical history to be able to diagnose and treat illnesses with various creams and pills. Mesopotamians had two kinds of medical practices, magical and physical. Unlike today they would use both on the same patient. They didn't see it as one as good and one as bad.[16]

The Mesopotamians made many technological discoveries. They were the first to use the potter's wheel to make better pottery, they used irrigation to get water to their crops, they used bronze metal (and later iron metal) to make strong tools and weapons, and used looms to weave cloth from wool.

The Jerwan Aqueduct (c. 688 BC) is made with stone arches and lined with waterproof concrete.[17]

For later technologies developed in the Mesopotamian region, now known as Iraq, see Persia below for developments under the ancient Persian Empire, and the Inventions in medieval Islam and Arab Agricultural Revolution articles for developments under the medieval Islamic Caliphates.

Egypt

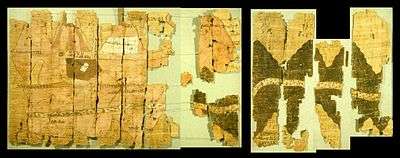

The Egyptians invented and used many simple machines, such as the ramp to aid construction processes. They were among the first to extract gold by large-scale mining using fire-setting, and the first recognisable map, the Turin papyrus shows the plan of one such mine in Nubia.

The Egyptians are known for building pyramids centuries before the creation of modern tools. Historians and archaeologists have found evidence that the Egyptian pyramids were built using three of what is called the Six Simple Machines, from which all machines are based. These machines are the inclined plane, the wedge, and the lever, which allowed the ancient Egyptians to move millions of limestone blocks which weighed approximately 3.5 tons (7,000 lbs.) each into place to create structures like the Great Pyramid of Giza, which is 481 feet (146.7 meters) high.[18]

Egyptian paper, made from papyrus, and pottery were mass-produced and exported throughout the Mediterranean basin. The wheel, however, did not arrive until foreign invaders introduced the chariot. They developed Mediterranean maritime technology including ships and lighthouses. Early construction techniques utilized by the Ancient Egyptians made use of bricks composed mainly of clay, sand, silt, and other minerals. These constructs would have been vital in flood control and irrigation, especially along the Nile delta.[19]

The screw pump is the oldest positive displacement pump.[20] The first records of a screw pump, also known as a water screw or Archimedes' screw, dates back to Ancient Egypt before the 3rd century BC.[20][21] The Egyptian screw, used to lift water from the Nile, was composed of tubes wound round a cylinder; as the entire unit rotates, water is lifted within the spiral tube to the higher elevation. A later screw pump design from Egypt had a spiral groove cut on the outside of a solid wooden cylinder and then the cylinder was covered by boards or sheets of metal closely covering the surfaces between the grooves.[20] The screw pump was later introduced from Egypt to Greece.[20]

For later technologies in Ptolemaic Egypt and Roman Egypt, see Ancient Greek technology and Roman technology, respectively. For later technology in medieval Arabic Egypt, see Inventions in medieval Islam and Arab Agricultural Revolution.

Indian subcontinent

The history of science and technology in the Indian subcontinent dates back to the earliest civilizations of the world. The Indus Valley civilization yields evidence of mathematics, hydrography, metrology, metallurgy, astronomy, medicine, surgery, civil engineering and sewage collection and disposal being practiced by its inhabitants.

The Indus Valley Civilization, situated in a resource-rich area (in modern Pakistan and northwestern India), is notable for its early application of city planning, sanitation technologies, and plumbing.[22] Cities in the Indus Valley offer some of the first examples of closed gutters, public baths, and communal granaries.

The Takshashila University was an important seat of learning in the ancient world. It was the center of education for scholars from all over Asia. Many Greek, Persian and Chinese students studied here under great scholars including Kautilya, Panini, Jivaka, and Vishnu Sharma.

The ancient system of medicine in India, Ayurveda was a significant milestone in Indian history. It mainly uses herbs as medicines. Its origins can be traced back to origin of Atharvaveda. The Sushruta Samhita (400 BC) by Sushruta has details about performing cataract surgery, plastic surgery, etc.

Ancient India was also at the forefront of seafaring technology - a panel found at Mohenjo-daro, depicts a sailing craft. Ship construction is vividly described in the Yukti Kalpa Taru, an ancient Indian text on Shipbuilding. (The Yukti Kalpa Taru had been translated and published by Prof. Aufrecht in his 'Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts').

Indian construction and architecture, called 'Vaastu Shastra', suggests a thorough understanding or materials engineering, hydrology, and sanitation. Ancient Indian culture was also pioneering in its use of vegetable dyes, cultivating plants including indigo and cinnabar. Many of the dyes were used in art and sculpture. The use of perfumes demonstrates some knowledge of chemistry, particularly distillation and purification processes.

China

The history of science and technology in China shows significant advances in science, technology, mathematics, and astronomy. The first recorded observations of comets, solar eclipses, and supernovae were made in China. Traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture and herbal medicine were also practiced. The Four Great Inventions of China: the compass, gunpowder, papermaking, and printing were among the most important technological advances, only known in Europe by the end of the Middle Ages.

According to the Scottish researcher Joseph Needham, the Chinese made many first-known discoveries and developments. Major technological contributions from China include early seismological detectors, matches, paper, the double-action piston pump, cast iron, the iron plough, the multi-tube seed drill, the suspension bridge, natural gas as fuel, the magnetic compass, the raised-relief map, the propeller, the crossbow, the south-pointing chariot, and gunpowder. Other Chinese discoveries and inventions from the Medieval period, according to Joseph Needham's research, include: block printing and movable type, phosphorescent paint, and the spinning wheel.

The solid-fuel rocket was invented in China about 1150 AD, nearly 200 years after the invention of black powder (which acted as the rocket's fuel). At the same time that the age of exploration was occurring in the West, the Chinese emperors of the Ming Dynasty also sent ships, some reaching Africa. But the enterprises were not further funded, halting further exploration and development. When Ferdinand Magellan's ships reached Brunei in 1521, they found a wealthy city that had been fortified by Chinese engineers, and protected by a breakwater. Antonio Pigafetta noted that much of the technology of Brunei was equal to Western technology of the time. Also, there were more cannons in Brunei than on Magellan's ships, and the Chinese merchants to the Brunei court had sold them spectacles and porcelain, which were rarities in Europe.

Persian Empire

The Qanat, a water management system used for irrigation, originated in Iran before the Achaemenid period of Persia. The oldest and largest known qanat is in the Iranian city of Gonabad which, after 2,700 years, still provides drinking and agricultural water to nearly 40,000 people.[23]

The earliest evidence of water wheels and watermills date back to the ancient Near East in the 4th century BC,[24] specifically in the Persian Empire before 350 BCE, in the regions of Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Persia (Iran).[25] This pioneering use of water power constituted the first human-devised motive force not to rely on muscle power (besides the sail).

In the 7th century AD, Persians in Afghanistan developed the first practical windmills. For later medieval technologies developed in Islamic Persia, see Inventions in medieval Islam and Arab Agricultural Revolution.

Mesoamerica and Andean Region

Lacking suitable beasts of burden and inhabiting domains often too mountainous or boggy for wheeled transport, the ancient civilizations of the Americas did not develop wheeled transport or the mechanics associated with animal power. Nevertheless, they produced advanced engineering including above ground and underground aqueducts, quake-proof masonry, artificial lakes, dykes, 'fountains,' pressurized water,[26] road ways and complex terracing. Equally, gold-working commenced early in Peru (2000 BCE),[27] and eventually copper, tin, lead and bronze were used.[28] Although metallurgy did not spread to Mesoamerica until the Middle Ages, it was employed here and in the Andes for sophisticated alloys and gilding. The Native Americans developed a complex understanding of the chemical properties or utility of natural substances, with the result that a majority of the world's early medicinal drugs and edible crops, many important adhesives, paints, fibres, plasters, and other useful items were the products of these civilizations. Perhaps the best-known Mesoamerican invention was rubber, which was used to create rubber bands, rubber bindings, balls, syringes, 'raincoats,' boots, and waterproof insulation on containers and flasks.

Hellenistic Mediterranean

The Hellenistic period of Mediterranean history began in the 4th century BC with Alexander's conquests, which led to the emergence of a Hellenistic civilization representing a synthesis of Greek and Near-Eastern cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean region, including the Balkans, Levant and Egypt.[29] With Ptolemaic Egypt as its intellectual center and Greek as the lingua franca, the Hellenistic civilization included Greek, Egyptian, Jewish, Persian and Phoenician scholars and engineers who wrote in Greek.[30]

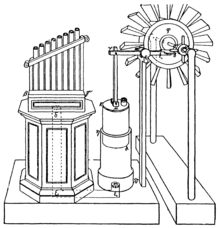

Hellenistic technology made significant progress from the 4th century BC, continuing up to and including the Roman period. Some inventions that are credited to the ancient Greeks are the following: bronze casting techniques, water organ (hydraulis), and torsion siege engine. Many of these inventions occurred late in the Hellenistic period, often inspired by the need to improve weapons and tactics in war.

Hellenistic engineers of the Eastern Mediterranean were responsible for a number of inventions and improvements to existing technology. Archimedes invented several machines. Hellenistic engineers often combined scientific research with the development of new technologies. Technologies invented by Hellenistic engineers include the ballistae, the piston pump, and primitive analog computers like the Antikythera mechanism. Hellenistic architects built domes, and were the first to explore the Golden ratio and its relationship with geometry and architecture.

Other Hellenistic innovations include torsion catapults, pneumatic catapults, crossbows, rutways, organs, the keyboard mechanism, differential gears, showers, dry docks, diving bells, odometer and astrolabes. In architecture, Hellenistic engineers constructed monumental lighthouses such as the Pharos and devised central heating systems. The Tunnel of Eupalinos is the earliest tunnel which has been excavated with a scientific approach from both ends.

Automata like automatic doors and other ingenious devices were built by Hellenistic engineers as Ctesibius and Philo of Byzantium. Greek technological treatises were scrupulously studied and advanced by later Byzantine, Arabic and Latin scholars, and provided some of the foundations for further technological advances in these civilizations.

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire expanded from Italia across the entire Mediterranean region between the 1st century BC and 1st century AD. Its most advanced and economically productive provinces outside of Italia were the Eastern Roman provinces in the Balkans, Asia Minor, Egypt, and the Levant, with Roman Egypt in particular being the wealthiest Roman province outside of Italia.[31][32]

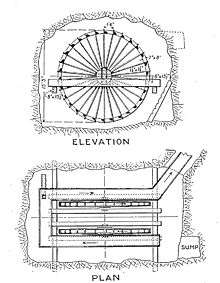

Roman technology supported Roman civilization and made the expansion of Roman commerce and Roman military possible over nearly a thousand years. The Roman Empire had an advanced set of technology for their time. Some of the Roman technology in Europe may have been lost during the turbulent eras of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Roman technological feats in many different areas such as civil engineering, construction materials, transport technology, and some inventions such as the mechanical reaper went unmatched until the 19th century. Romans developed an intensive and sophisticated agriculture, expanded upon existing iron working technology, created laws providing for individual ownership, advanced stonemasonry technology, advanced road-building (exceeded only in the 19th century), military engineering, civil engineering, spinning and weaving and several different machines like the Gallic reaper that helped to increase productivity in many sectors of the Roman economy. They also developed water power through building aqueducts on a grand scale, using water not just for drinking supplies but also for irrigation, powering water mills and in mining. They used drainage wheels extensively in deep underground mines, one device being the reverse overshot water-wheel. They were the first to apply hydraulic mining methods for prospecting for metal ores, and for extracting those ores from the ground when found using a method known as hushing.

Roman engineers have built triumphal arches, amphitheatres, aqueducts, public baths, true arch bridges, harbours, dams, vaults and domes on a very large scale across their Empire. Notable Roman inventions include the book (Codex), glass blowing and concrete. Because Rome was located on a volcanic peninsula, with sand which contained suitable crystalline grains, the concrete which the Romans formulated was especially durable. Some of their buildings have lasted 2000 years, to the present day. Roman society had also carried over the design of a door lock with tumblers and springs from Greece. Like many other aspects of innovation and culture that were carried on from Greece to Rome, the lines between where each one originated from have become skewed over time. These mechanisms were highly sophisticated and intricate for the era.[33]

Roman civilization was highly urbanized by pre-modern standards. Many cities of the Roman Empire had over 100,000 inhabitants with the capital Rome being the largest metropolis of antiquity. Features of Roman urban life included multistory apartment buildings called insulae, street paving, public flush toilets, glass windows and floor and wall heating. The Romans understood hydraulics and constructed fountains and waterworks, particularly aqueducts, which were the hallmark of their civilization. They exploited water power by building water mills, sometimes in series, such as the sequence found at Barbegal in southern France and suspected on the Janiculum in Rome. Some Roman baths have lasted to this day. The Romans developed many technologies which were apparently lost in the Middle Ages, and were only fully reinvented in the 19th and 20th centuries. They also left texts describing their achievements, especially Pliny the Elder, Frontinus and Vitruvius.

Other less known Roman innovations include cement, boat mills, arch dams and possibly tide mills.

In Roman Egypt, Heron of Alexandria invented the aeolipile, a basic steam-powered device, and demonstrated knowledge of mechanic and pneumatic systems. He was also the first to experiment with a wind-powered mechanical device, a windwheel. He also described a vending machine. However, his inventions were primarily toys, rather than practical machines.

See also

References

- Clare, I. S. (1906). Library of universal history: containing a record of the human race from the earliest historical period to the present time; embracing a general survey of the progress of mankind in national and social life, civil government, religion, literature, science and art. New York: Union Book. Page 1519 (cf., Ancient history, as we have already seen, ended with the fall of the Western Roman Empire; [...])

- United Center for Research and Training in History. (1973). Bulgarian historical review. Sofia: Pub. House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Page 43. (cf. ... in the history of Western Europe, which marks both the end of ancient history and the beginning of the Middle Ages, is the fall of the Western Empire.)

- Robinson, C. A. (1951). Ancient history from prehistoric times to the death of Justinian. New York: Macmillan.

- Breasted, J. H. (1916). Ancient times, a history of the early world: an introduction to the study of ancient history and the career of early man. Boston: Ginn and Company.

- Myers, P. V. N. (1916). Ancient history. New York [etc.]: Ginn and company.

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060422.

- D.T. Potts (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. p. 285.

- Attema, P. A. J.; Los-Weijns, Ma; Pers, N. D. Maring-Van der (December 2006). "Bronocice, Flintbek, Uruk, JEbel Aruda and Arslantepe: The Earliest Evidence Of Wheeled Vehicles In Europe And The Near East". Palaeohistoria. University of Groningen. 47/48: 10–28 (11).

- Paipetis, S. A.; Ceccarelli, Marco (2010). The Genius of Archimedes -- 23 Centuries of Influence on Mathematics, Science and Engineering: Proceedings of an International Conference held at Syracuse, Italy, June 8-10, 2010. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 416. ISBN 9789048190911.

- Faiella, Graham (2006). The Technology of Mesopotamia. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 27. ISBN 9781404205604.

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 4. ISBN 9781575060422.

- Woods, Michael; Mary B. Woods (2000). Ancient Machines: From Wedges to Waterwheels. USA: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 58. ISBN 0-8225-2994-7.

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 4. ISBN 9781575060422.

- Stephanie Dalley and John Peter Oleson (January 2003). "Sennacherib, Archimedes, and the Water Screw: The Context of Invention in the Ancient World", Technology and Culture 44 (1).

- Oleson, John Peter (2000). "Water-Lifting". In Wikander, Örjan (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Water Technology. Technology and Change in History. 2. Leiden: Brill. pp. 217–302 (242–251). ISBN 90-04-11123-9.

- Robert Alan Chadwick, First Civilization: Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt (2) (London: Equinox Publishing Ltd, 2005), 119.

- T Jacobsen and S Lloyd, Sennacherib's Aqueduct at Jerwan, Chicago University Press, (1935)

- Wood, Michael (2000). Ancient Machines: From Grunts to Graffiti. Minneapolis, MN: Runestone Press. pp. 35, 36. ISBN 0-8225-2996-3.

- Jerzy Trzciñski , Malgorzata Zaremba , Sawomir Rzepka , Fabian Welc , and Tomasz Szczepañski. “Preliminary Report on Engineering Properties and Environmental Resistance of Ancient Mud Bricks from Tell El-retaba Archaeological Site in the Nile Delta,” Studia Quarternaria 33, no. 1 (2016): 55.

- Stewart, Bobby Alton; Terry A. Howell (2003). Encyclopedia of water science. USA: CRC Press. p. 759. ISBN 0-8247-0948-9.

- "Screw". Encyclopædia Britannica online. The Encyclopaedia Britannica Co. 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- Teresi, Dick (2002). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science--from the Babylonians to the Maya. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 351–352. ISBN 0-684-83718-8.

- Ward English, Paul (June 21, 1968). "The Origin and Spread of Qanats in the Old World". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. JSTOR. 112 (3): 170–181. JSTOR 986162.

- Terry S. Reynolds, Stronger than a Hundred Men: A History of the Vertical Water Wheel, JHU Press, 2002 ISBN 0-8018-7248-0, p. 14

- Selin, Helaine (2013). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Westen Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 282. ISBN 9789401714167.

- A’ndrea Messer (February 8, 2011). "Maya plumbing, first pressurized water feature found in New World". Penn State News. Archived from the original on 2013-02-08. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- K. Kris Hirst. "A Walking Tour of Machu Picchu, Peru". about.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- Lechtman, Heather (1985). "The Significance of Metals in Pre-Columbian Andean Culture". Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38, No. 5: 9–37 – via JSTOR.

- Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- George G. Joseph (2000). The Crest of the Peacock, p. 7-8. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00659-8.

- Maddison, Angus (2007), Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History, p. 55, table 1.14, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1

- Hero (1899). "Pneumatika, Book ΙΙ, Chapter XI". Herons von Alexandria Druckwerke und Automatentheater (in Greek and German). Wilhelm Schmidt (translator). Leipzig: B.G. Teubner. pp. 228–232.

- Naif A. Haddad, "Critical Review, Assessment and Investigation of Ancient Technology Evolution of Door Locking Mechanisms in S.E. Mediterranean," Mediterranean Archaeology & Archaeometry 16, no. 1: 43-74.

Further reading

- Humphrey, J. W. (2006). Ancient technology. Greenwood guides to historic events of the ancient world. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

- Rojcewicz, R. (2006). The gods and technology: a reading of Heidegger. SUNY series in theology and continental thought. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Krebs, R. E., & Krebs, C. A. (2004). Groundbreaking scientific experiments, inventions, and discoveries of the ancient world. Groundbreaking scientific experiments, inventions, and discoveries through the ages. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

- Childress, D. H. (2000). Technology of the gods: the incredible sciences of the ancients. Kempton, Ill: Adventures Unlimited Press.

- Landels, J. G. (2000). Engineering in the ancient world. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- James, P., & Thorpe, N. (1995). Ancient inventions. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Hodges, H. (1992). Technology in the ancient world. New York: Barnes & Noble.

- National Geographic Society (U.S.). (1986). Builders of the ancient world: marvels of engineering. Washington, D.C.: The Society.

- American Ceramic Society, Kingery, W. D., & Lense, E. (1985). Ancient technology to modern science. Ceramics and civilization, v. 1. Columbus, Ohio: American Ceramic Society.

- Brown, M. (1966). On the theory and measurement of technological change. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P.

- Forbes, R. J. (1964). Studies in ancient technology. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

External links