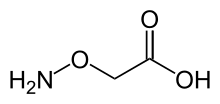

Aminooxyacetic acid

Aminooxyacetic acid, often abbreviated AOA or AOAA, is a compound that inhibits 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (GABA-T) activity in vitro and in vivo, leading to less gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) being broken down.[1] Subsequently, the level of GABA is increased in tissues. At concentrations high enough to fully inhibit 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase activity, aminooxyacetic acid is indicated as a useful tool to study regional GABA turnover in rats.[2]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-(aminooxy)acetic acid | |

| Other names

Carboxymethoxylamine Hydroxylamineacetic acid U-7524 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| MeSH | Aminooxyacetic+Acid |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C2H5NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 91.066 |

| Density | 1.375 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 138 °C (280 °F; 411 K) |

| Boiling point | 326.7 °C (620.1 °F; 599.8 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 151 °C (304 °F; 424 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Aminooxyacetic acid is a general inhibitor of pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes (this includes GABA-T).[3] It functions as an inhibitor by attacking the Schiff base linkage between PLP and the enzyme, forming oxime type complexes.[3]

Aminooxyacetic acid inhibits aspartate aminotransferase, another PLP-dependent enzyme, which is an essential part of the malate-aspartate shuttle.[4] The inhibition of the malate-aspartate shuttle prevents the reoxidation of cytosolic NADH by the mitochondria in nerve terminals.[4] Also in the nerve terminals, aminooxyacetic acid prevents the mitochondria from utilizing pyruvate generated from glycolysis, thus leading to a bioenergetic state similar to that of hypoglycemia.[4] Aminooxyacetic acid has been shown to cause excitotoxic lesions of the striatum, similar to Huntington's disease, potentially due to its impairment of mitochondrial energy metabolism.[5] Aminooxyacetic acid was previously used in a clinical trial to reduce symptoms of Huntington's disease by increasing GABA levels in the brain.[6] However, the patients who received the aminooxyacetic acid treatment failed to show clinical improvement and suffered from side effects such as drowsiness, ataxia, seizures, and psychotic behavior when the dosage was increased beyond 2 mg per kilogram per day.[6] Also, the inhibition of aspartate aminotransferase by aminooxyacetic acid has clinical implications for the treatment of breast cancer, since a decrease in glycolysis disrupts breast adenocarcinoma cells more than normal cells.[7]

Moreover, selective inhibition of aspartate aminotransferase with aminooxyacetic acid ameliorated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in a therapeutic mouse model by reprograming the differentiation of pro-inflammatory T helper 17 cells, that boost the immune system, towards induced anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells.[8]

Aminooxyacetic acid has been studied as a treatment for tinnitus.[9][10][11] One study showed that about 20% of patients with tinnitus had a decrease in its severity when treated with aminooxyacetic acid.[11] However, about 70% of those patients reported side effects, mostly nausea and disequilibrium.[11] Thus, the investigators of the study concluded that the incidence of the side effects makes aminooxyacetic acid unsuitable to treat tinnitus.[11]

Aminooxyacetic acid also has anticonvulsant properties.[12] At high dosages, it can act as a convulsant agent in mice and rats.[13]

Aminooxyacetic acid can also inhibit 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase preventing ethylene synthesis, which can increase the vase life of cut flowers.[14]

History

Aminooxyacetic acid was first described by Werner in 1893, and was prepared by the hydrolysis of ethylbenzhydroximinoacetic acid.[15][16][17][18] In 1936, Anchel and Shoenheimer used aminooxyacetic acid to isolate ketones from natural sources.[17] Also in 1936, Kitagawa and Takani described the preparation of aminooxyacetic acid by the condensation of benzhydroxamic acid and ethyl bromoacetate, followed by hydrolysis by hydrochloric acid.[19]

References

- Wallach, D. (1961). "Studies on the GABA pathway. I. The inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid-alpha-ketoglutaric acid transaminase in vitro and in vivo by U-7524 (amino-oxyacetic acid)". Biochemical Pharmacology. 5 (4): 323–331. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(61)90023-5. PMID 13782815.

- Wolfgang Löscher; Dagmar Hönack; Martina Gramer (1989). "Use of Inhibitors of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Transaminase for the Estimation of GABA Turnover in Various Brain Regions of Rats: A Reevaluation of Aminooxyacetic Acid". Journal of Neurochemistry. 53 (6): 1737–1750. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09239.x. PMID 2809589.

- Beeler, T.; Churchich, J. (1976). "Reactivity of the phosphopyridoxal groups of cystathionase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 251 (17): 5267–5271. PMID 8458.

- Risto A. Kauppinen; Talvinder S. Sihra; David G. Nicholls (1987). "Aminooxyacetic acid inhibits the malate-aspartate shuttle in isolated nerve terminals and prevents the mitochondria from utilizing glycolytic substrates". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 930 (2): 173–178. doi:10.1016/0167-4889(87)90029-2. PMID 3620514.

- Beal, M.; Swartz, K.; Hyman, B.; Storey, E.; Finn, S.; Koroshetz, W. (1991). "Aminooxyacetic acid results in excitotoxin lesions by a novel indirect mechanism". Journal of Neurochemistry. 57 (3): 1068–1073. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08258.x. PMID 1830613.

- Perry, T.; Wright, J.; Hansen, S.; Allan, B.; Baird, P.; MacLeod, P. (1980). "Failure of aminooxyacetic acid therapy in Huntington disease". Neurology. 30 (7 Pt 1): 772–775. doi:10.1212/wnl.30.7.772. PMID 6446691.

- Thornburg, J. M.; Nelson, K. K.; Clem, B. F.; Lane, A. N.; Arumugam, S.; Simmons, A.; Eaton, J. W.; Telang, S.; Chesney, J. (2008). "Targeting aspartate aminotransferase in breast cancer". Breast Cancer Research. 10 (5): R84. doi:10.1186/bcr2154. PMC 2614520. PMID 18922152.

- Xu, T.; Kelly, M.; et, all. (2017). "Metabolic control of TH17 and induced Treg cell balance by an epigenetic mechanism". Nature. 548 (7666): 228–233. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..228X. doi:10.1038/nature23475. PMC 6701955. PMID 28783731.

- Reed, H.; Meltzer, J.; Crews, P.; Norris, C.; Quine, D.; Guth, P. (1985). "Amino-oxyacetic acid as a palliative in tinnitus". Archives of Otolaryngology. 111 (12): 803–805. doi:10.1001/archotol.1985.00800140047008. PMID 2415097.

- Blair, P.; Reed, H. (1986). "Amino-oxyacetic acid: A new drug for the treatment of tinnitus". Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society. 138 (6): 17–19. PMID 3734755.

- Guth, P.; Risey, J.; Briner, W.; Blair, P.; Reed, H.; Bryant, G.; Norris, C.; Housley, G.; Miller, R. (1990). "Evaluation of amino-oxyacetic acid as a palliative in tinnitus". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 99 (1): 74–79. doi:10.1177/000348949009900113. PMID 1688487.

- Davanzo, J.; Greig, M.; Cronin, M. (1961). "Anticonvulsant properties of amino-oxyacetic acid". American Journal of Physiology. 201 (5): 833–837. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1961.201.5.833. PMID 13883717.

- Wood, J.; Peesker, S. (1973). "The role of GABA metabolism in the convulsant and anticonvulsant actions of aminooxyacetic acid". Journal of Neurochemistry. 20 (2): 379–387. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb12137.x. PMID 4698285.

- Broun, R.; Mayak, S. (1981). "Aminooxyacetic acid as an inhibitor of ethylenesynthesis and senescence in carnation flowers". Scientia Horticulturae. 15 (3): 277–282. doi:10.1016/0304-4238(81)90038-8.

- Werner, A. (1893). "Ueber Hydroxylaminessigsäure und Derivate derselben". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 26 (2): 1567–1571. doi:10.1002/cber.18930260274.

- Werner, A.; Sonnenfeld, E. (1894). "Ueber Hydroxylaminessigsäure und α-Hydroxylaminpropionsäure". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 27 (3): 3350–3354. doi:10.1002/cber.189402703141.

- Anchel, Marjorie; Schoenheimer, Rudolf (1936). "Reagents for the isolation of carbonyl compounds from unsaponifiable material" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 114 (2): 539–546. Retrieved 2011-05-20.

- Borek, E.; Clarke, H. T. (1936). "Carboxymethoxylamine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 58 (10): 2020–2021. doi:10.1021/ja01301a058.

- Kitagawa, Matsunosuke; Takani, A. (1936). "Studies on a Diamino Acid, Canavanin, IV. The Constitution of Canavanin and Canalin". Journal of Biochemistry. 23: 181–185. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a125537.