Alcohol flush reaction

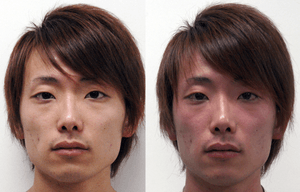

Alcohol flush reaction (AFR) is a condition in which a person develops flushes or blotches associated with erythema on the face, neck, shoulders, and in some cases, the entire body after consuming alcoholic beverages. The reaction is the result of an accumulation of acetaldehyde, a metabolic byproduct of the catabolic metabolism of alcohol, and is caused by an aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 deficiency.[4]

| Alcohol flush reaction | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Asian flush syndrome, Asian flush reaction, Asian glow, Asian red face glow |

| |

| Facial flushing. Before (left) and after (right) drinking alcohol. A 22-year-old East Asian man who is ALDH2 heterozygote showing the reaction.[1] | |

| Specialty | Toxicology |

| Frequency | 36% of East Asians[2][1][3] |

This syndrome has been associated with lower than average rates of alcoholism, possibly due to its association with adverse effects after drinking alcohol.[5] However, it has also been associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer in those who do drink.[1][6][7]

Approximately 30 to 50% of East Asians (Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans) show characteristic physiological responses to drinking alcohol that includes facial flushing, nausea, headaches and a fast heart rate.[1][2][3][8]

Signs and symptoms

Individuals who experience the alcohol flushing reaction may be less prone to alcoholism. Disulfiram, a drug sometimes given as treatment for alcoholism, works by inhibiting acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, causing a five to tenfold increase in the concentration of acetaldehyde in the body. The resulting irritating flushing reaction tends to discourage affected individuals from drinking.[9][10]

The most obvious symptom is flushing on a person's face and body after drinking alcohol.[4] Other effects include "nausea, headache and general physical discomfort".[11]

Many cases of alcohol-induced respiratory reactions, which involve rhinitis and worsening of asthma, develop within 1–60 minutes of drinking alcohol and are due to the same causes as flush reactions.[12]

Causes

Around 80% of East Asians carry an allele of the gene coding for the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase called ADH1B*2, which results in the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme converting alcohol to toxic acetaldehyde more quickly than other gene variants common outside of East Asia.[5][13] In about 30–50% of East Asians, the rapid accumulation of acetaldehyde is worsened by another gene variant, the mitochondrial ALDH2*2 allele, which results in a less functional acetaldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme, responsible for the breakdown of acetaldehyde.[13]

Genetics

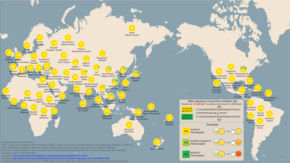

Alcohol flush reaction is best known as a condition that is experienced by people of East Asian descent. According to the analysis by HapMap project, the rs671 (ALDH2*2) allele of the ALDH2 responsible for the flush reaction is rare among Europeans and Sub-Saharan Africans. 30% to 50% of people of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean ancestry have at least one ALDH2*2 allele.[8] The rs671 form of ALDH2, which accounts for most incidents of alcohol flush reaction worldwide, is native to East Asia and most common in southeastern China. It most likely originated among Han Chinese in central China.[14] Another analysis correlates the rise and spread of rice cultivation in South China with the spread of the allele.[5] The reasons for this positive selection are not known, but it has been hypothesized that elevated concentrations of acetaldehyde may have conferred protection against certain parasitic infections, such as Entamoeba histolytica.[15]

Pathophysiology

Those with facial flushing due to ALDH2 deficiency may be homozygotes, with two alleles of low activity, or heterozygotes, with one low-activity and one normal allele. Homozygotes for the trait find consumption of large amounts of alcohol to be so unpleasant that they are generally protected from esophageal cancer, but heterozygotes are able to continue drinking. However, an ALDH2-deficient drinker has four to eight times the risk of developing esophageal cancer as a drinker not deficient in the enzyme.[1][7]

Because most East Asians have a variant in the ADH gene, this risk is lowered somewhat because the ADH variant reduces the risk of esophageal cancer four-fold. However, ALDH2-deficient people who do not carry this ADH variant are at the highest risk of cancer as these risk factors act in a multiplicative manner through increasing exposure time to salivary acetaldehyde.[7]

The idea that acetaldehyde is the cause of the flush is also shown by the clinical use of disulfiram (Antabuse), which blocks the removal of acetaldehyde from the body via ALDH inhibition. The high acetaldehyde concentrations described share similarity to symptoms of the flush (flushing of the skin, accelerated heart rate, shortness of breath, throbbing headache, mental confusion and blurred vision).[16]

Diagnosis

For measuring the level of flush reaction to alcohol, the most accurate method is to determine the level of acetaldehyde in the blood stream. This can be measured through both a breathalyzer test or a blood test.[17] Additionally, measuring the amount of alcohol metabolizing enzymes alcohol dehydrogenases and aldehyde dehydrogenase through genetic testing can predict the amount of reaction that one would have. More crude measurements can be made through measuring the amount of redness in the face of an individual after consuming alcohol. Computer and phone applications can be used to standardize this measurement.

Similar conditions

- Alcohol-induced respiratory reactions including rhinitis and exacerbations of asthma appear, in many cases, due to the direct actions of ethanol.

- Rosacea, also known as gin blossoms, is a chronic facial skin condition in which capillaries are excessively reactive, leading to redness from flushing or telangiectasia. Rosacea has been mistakenly attributed to alcoholism because of its similar appearance to the temporary flushing of the face that often accompanies the ingestion of alcohol.

- Degreaser's flush – a flushing condition arising from consuming alcohol shortly before or during inhalation of trichloroethylene (TCE), an organic solvent with suspected carcinogenic properties.

- Carcinoid syndrome – episodes of severe flushing precipitated by alcohol, stress and certain foods. May also be associated with intense diarrhea, wheezing and weight loss.

- Red ear syndrome,[18] thought by many to be triggered by alcohol among other causes.

References

- Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A (March 2009). "The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption". PLOS Medicine. 6 (3): e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050. PMC 2659709. PMID 19320537.

- Lee H, Kim SS, You KS, Park W, Yang JH, Kim M, Hayman LL (2014). "Asian flushing: genetic and sociocultural factors of alcoholism among East asians". Gastroenterology Nursing. 37 (5): 327–36. doi:10.1097/SGA.0000000000000062. PMID 25271825.

- J. Yoo, Grace; Odar, Alan Y. (2014). Handbook of Asian American Health. Springer. p. 132. ISBN 978-1493913442.

- Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A (March 2009). "The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption". PLOS Medicine. 6 (3): e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050. PMC 2659709. PMID 19320537.

- Peng Y, Shi H, Qi XB, Xiao CJ, Zhong H, Ma RL, Su B (January 2010). "The ADH1B Arg47His polymorphism in east Asian populations and expansion of rice domestication in history". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 15. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-15. PMC 2823730. PMID 20089146.

- Alcohol Flush Signals Increased Cancer Risk among East Asians March 23, 2009 News Release – National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- Lee, Chien-Hung; Lee, Jang-Ming; Wu, Deng-Chyang; Goan, Yih-Gang; Chou, Shah-Hwa; Wu, I.-Chen; Kao, Ein-Long; Chan, Te-Fu; Huang, Meng-Chuan; Chen, Pei-Shih; Lee, Chun-Ying (2008). "Carcinogenetic impact of ADH1B and ALDH2 genes on squamous cell carcinoma risk of the esophagus with regard to the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and betel quid". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (6): 1347–56. doi:10.1002/ijc.23264. ISSN 1097-0215. PMID 18033686.

- "Rs671".

- "Disulfiram". MedlinePlus Drug Information. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Toxicity, Disulfiram at eMedicine

- http://dujs.dartmouth.edu/fall-2009/esophageal-cancer-and-the-‘asian-glow’

- Adams KE, Rans TS (December 2013). "Adverse reactions to alcohol and alcoholic beverages". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 111 (6): 439–45. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.09.016. PMID 24267355.

- Eng MY, Luczak SE, Wall TL (2007). "ALDH2, ADH1B, and ADH1C genotypes in Asians: a literature review". Alcohol Research & Health. 30 (1): 22–27. PMC 3860439. PMID 17718397.

- Li H, Borinskaya S, Yoshimura K, Kal'ina N, Marusin A, Stepanov VA, Qin Z, Khaliq S, Lee MY, Yang Y, Mohyuddin A, Gurwitz D, Mehdi SQ, Rogaev E, Jin L, Yankovsky NK, Kidd JR, Kidd KK (May 2009). "Refined geographic distribution of the oriental ALDH2*504Lys (nee 487Lys) variant". Annals of Human Genetics. 73 (Pt 3): 335–45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00517.x. PMC 2846302. PMID 19456322.

- Oota; et al. (2004). "The evolution and population genetics of the ALDH2 locus: random genetic drift, selection, and low levels of recombination". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 93–109. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00060.x. PMID 15008789.

- Wright C, Moore RD (June 1990). "Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism". The American Journal of Medicine. 88 (6): 647–55. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(90)90534-K. PMID 2189310.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2010-07-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Boulton P, Purdy RA, Bosch EP, Dodick DW (February 2007). "Primary and secondary red ear syndrome: implications for treatment". Cephalalgia. 27 (2): 107–10. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01270.x. PMID 17257229.