Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome

Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome (WKS) is the combined presence of Wernicke encephalopathy (WE) and alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome. Due to the close relationship between these two disorders, people with either are usually diagnosed with WKS as a single syndrome. It mainly causes vision changes, ataxia and impaired memory.[1]

| Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Korsakoff's psychosis, alcoholic encephalopathy[1] |

| |

| Thiamine | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

The cause of the disorder is thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency. This can occur due to beriberi, Wernicke encephalopathy, and alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome. These disorders may manifest together or separately. WKS is usually secondary to alcohol abuse.

Wernicke encephalopathy and WKS are most commonly seen in people with an alcohol use disorder. Failure in diagnosis of WE and thus treatment of the disease leads to death in approximately 20% of cases, while 75% are left with permanent brain damage associated with WKS.[2] Of those affected, 25% require long-term institutionalization in order to receive effective care.[2][3]

Signs and symptoms

The syndrome is a combined manifestation of two namesake disorders, Wernicke encephalopathy and alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome. It involves an acute Wernicke-encephalopathy phase, followed by the development of a chronic alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome phase.[4]

Wernicke encephalopathy

WE is characterized by the presence of a triad of symptoms:[5]

- Ocular disturbances (ophthalmoplegia)

- Changes in mental state (confusion)

- Unsteady stance and gait (ataxia)

This triad of symptoms results from a deficiency in vitamin B1 which is an essential coenzyme. The aforementioned changes in mental state occur in approximately 82% of patients' symptoms of which range from confusion, apathy, inability to concentrate, and a decrease in awareness of the immediate situation they are in. If left untreated, WE can lead to coma or death. In about 29% of patients, ocular disturbances consist of nystagmus and paralysis of the lateral rectus muscles or other muscles in the eye. A smaller percentage of patients experience a decrease in reaction time of the pupils to light stimuli and swelling of the optic disc which may be accompanied by retinal hemorrhage. Finally, the symptoms involving stance and gait occur in about 23% of patients and result from dysfunction in the cerebellum and vestibular system. Other symptoms that have been present in cases of WE are stupor, low blood pressure (hypotension), elevated heart rate (tachycardia), as well as hypothermia, epileptic seizures and a progressive loss of hearing.[5]

About 19% of patients have none of the symptoms in the classic triad at first diagnosis of WE; however, usually one or more of the symptoms develops later as the disease progresses.[5]

Alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome

The DSM-V classifies Korsakoff syndrome under Substance/Medication-Induced Major or Mild Neurocognitive Disorders, specifically alcohol-induced amnestic confabulatory.[6] The diagnostic criteria defined as necessary for diagnosis includes, prominent amnesia, forgetting quickly, and difficulty learning. Presence of thiamine deficient encephalopathy can occur in conjunction with these symptoms.[6]

Despite the assertion that alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome must be caused by the use of alcohol, there have been several cases where it has developed from other instances of thiamine deficiency resulting from gross malnutrition due to conditions such as; stomach cancer, anorexia nervosa, and gastrectomy.[7]

Cognitive effects

Several cases have been documented where Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome has been seen on a large scale. In 1947, 52 cases of WKS were documented in a prisoner of war hospital in Singapore where the prisoners' diets included less than 1 mg of thiamine per day. Such cases provide an opportunity to gain an understanding of what effects this syndrome has on cognition. In this particular case, cognitive symptoms included insomnia, anxiety, difficulties in concentration, loss of memory for the immediate past, and gradual degeneration of mental state; consisting of confusion, confabulation, and hallucinations.[2] In other cases of WKS, cognitive effects such as severely disrupted speech, giddiness, and heavy-headedness have been documented. In addition to this, it has been noted that some patients displayed an inability to focus, and the inability of others to catch patients' attention.[8]

In a study conducted in 2003 by Brand et al. on the cognitive effects of WKS, the researchers used a neuropsychological test battery which included tests of intelligence, speed of information processing, memory, executive function and cognitive estimation. They found that patients suffering from WKS showed impairments in all aspects of this test battery but most noticeably, on the cognitive estimation tasks. This task required subjects to estimate a physical quality such as size, weight, quantity or time (i.e. What is the average length of a shower?), of a particular item. Patients with WKS performed worse than normal control participants on all of the tasks in this category. The patients found estimations involving time to be the most difficult, whereas quantity was the easiest estimation to make. Additionally, the study included a category for classifying "bizarre" answers, which included any answer that was far outside of the normal range of expected responses. WKS patients did give answers that could fall into such a category and these included answers such as 15s or 1 hour for the estimated length of a shower, or 4 kg or 15 tonnes as the weight of a car.[9]

Memory deficits

As mentioned previously, the amnesic symptoms of WKS include both retrograde and anterograde amnesia.[4] The retrograde deficit has been demonstrated through an inability of WKS patients to recall or recognize information for recent public events. The anterograde memory loss is demonstrated through deficits in tasks that involve encoding and then recalling lists of words and faces, as well as semantic learning tasks. WKS patients have also demonstrated difficulties in perseveration as evidenced by a deficit in performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.[4] The retrograde amnesia that accompanies WKS can extend as far back as twenty to thirty years, and there is generally a temporal gradient seen, where earlier memories are recalled better than more recent memories.[10] It has been widely accepted that the critical structures that lead to the memory impairment in WKS are the mammillary bodies, and the thalamic regions.[11] Despite the aforementioned memory deficits, non-declarative memory functions appear to be intact in WKS patients. This has been demonstrated through measures that assess perceptual priming.[4]

Other studies have shown deficits in recognition memory and stimulus-reward associative functions in patients with WKS.[11] The deficit in stimulus-reward functions was demonstrated by Oscar-Berman and Pulaski who presented patients with reinforcements for certain stimuli but not others, and then required the patients to distinguish the rewarded stimuli from the non-rewarded stimuli. WKS patients displayed significant deficits in this task. The researchers were also successful in displaying a deficit in recognition memory by having patients make a yes/no decision as to whether a stimulus was familiar (previously seen) or novel (not previously seen). The patients in this study also showed a significant deficit in their ability to perform this task.[11]

Confabulation

People with WKS often show confabulation, spontaneous confabulation being seen more frequently than provoked confabulation.[12] Spontaneous confabulations refer to incorrect memories that the patient holds to be true, and may act on, arising spontaneously without any provocation. Provoked confabulations can occur when a patient is cued to give a response, this may occur in test settings. The spontaneous confabulations viewed in WKS are thought to be produced by an impairment in source memory, where they are unable to remember the spatial and contextual information for an event, and thus may use irrelevant or old memory traces to fill in for the information that they cannot access. It has also been suggested that this behaviour may be due to executive dysfunction where they are unable to inhibit incorrect memories or because they are unable to shift their attention away from an incorrect response.[12]

Causes

WKS is usually found in people who have used alcohol chronically. Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome results from thiamine deficiency. It is generally agreed that Wernicke encephalopathy results from severe acute deficiency of thiamine (vitamin B1), whilst Korsakoff's psychosis is a chronic neurologic sequela of Wernicke encephalopathy. The metabolically active form of thiamine is thiamine pyrophosphate, which plays a major role as a cofactor or coenzyme in glucose metabolism. The enzymes that are dependent on thiamine pyrophosphate are associated with the citric acid cycle (also known as the Krebs cycle), and catalyze the oxidation of pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate and branched chain amino acids. Thus, anything that encourages glucose metabolism will exacerbate an existing clinical or sub-clinical thiamine deficiency.[13]

As stated above, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome in the United States is usually found in malnourished chronic alcoholics, though it is also found in patients who undergo prolonged intravenous (IV) therapy without vitamin B1 supplementation, gastric stapling, intensive care unit (ICU) stays, hunger strikes, or people with eating disorders. In some regions, physicians have observed thiamine deficiency brought about by severe malnutrition, particularly in diets consisting mainly of polished rice, which is thiamine-deficient. The resulting nervous system ailment is called beriberi. In individuals with sub-clinical thiamine deficiency, a large dose of glucose (either as sweet food, etc. or glucose infusion) can precipitate the onset of overt encephalopathy.[14][15][16]

Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome in people with chronic alcohol use particularly is associated with atrophy/infarction of specific regions of the brain, especially the mammillary bodies. Other regions include the anterior region of the thalamus (accounting for amnesic symptoms), the medial dorsal thalamus, the basal forebrain, the median and dorsal raphe nuclei,[17] and the cerebellum.[18]

One as-yet-unreplicated study has associated susceptibility to this syndrome with a hereditary deficiency of transketolase, an enzyme that requires thiamine as a coenzyme.[19]

Post-gastrectomy

The fact that gastrointestinal surgery can lead to the development of WKS was demonstrated in a study that was completed on three patients who recently undergone a gastrectomy. These patients had developed WKS but were not alcoholics and had never suffered from dietary deprivation. WKS developed between 2 and 20 years after the surgery.[20] There were small dietary changes that contributed to the development of WKS but overall the lack of absorption of thiamine from the gastrointestinal tract was the cause. Therefore, it must be ensured that patients who have undergone gastrectomy have a proper education on dietary habits, and carefully monitor their thiamine intake. Additionally, an early diagnosis of WKS, should it develop, is very important.[20]

Alcohol–thiamine interactions

Strong evidence suggests that ethanol interferes directly with thiamine uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. Ethanol also disrupts thiamine storage in the liver and the transformation of thiamine into its active form.[21] The role of alcohol consumption in the development of WKS has been experimentally confirmed through studies in which rats were subjected to alcohol exposure and lower levels of thiamine through a low-thiamine diet.[22] In particular, studies have demonstrated that clinical signs of the neurological problems that result from thiamine deficiency develop faster in rats that have received alcohol and were also deficient in thiamine than rats who did not receive alcohol.[22] In another study, it was found that rats that were chronically fed alcohol had significantly lower liver thiamine stores than control rats. This provides an explanation for why alcoholics with liver cirrhosis have a higher incidence of both thiamine deficiency and WKS.[21]

Pathophysiology

The vitamin thiamine also referred to as Vitamin B1, is required by three different enzymes to allow for conversion of ingested nutrients into energy. [13] Thiamine can not be produced in the body and must be obtained through diet and supplementation. [23] The duodenum is responsible for absorbing thiamine. The liver can store thiamine for 18 days.[13] Prolonged and frequent consumption of alcohol causes a decreased ability to absorb thiamine in the duodenum. Thiamine deficiency is also related to malnutrition from poor diet, impaired use of thiamine by the cells and impaired storage in the liver. [23]Without thiamine the Kreb's Cycle enzymes pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (alpha-KGDH) are impaired.[13] The impaired functioning of the Kreb's Cycle results in inadequate production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or energy for the cells functioning. [13] Energy is required by the brain for proper functioning and use of its neurotransmitters. Injury to the brain occurs when neurons that require high amounts of energy from thiamine dependent enzymes are not supplied with enough energy and die. [13]

Brain atrophy associated with WKS occurs in the following regions of the brain: the mammillary bodies, the thalamus, the periaqueductal grey, the walls of the 3rd ventricle, the floor of the 4th ventricle, the cerebellum, and the frontal lobe. In addition to the damage seen in these areas there have been reports of damage to cortex, although it was noted that this may be due to the direct toxic effects of alcohol as opposed to thiamine deficiency that has been attributed as the underlying cause of Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome.[24]

The amnesia that is associated with this syndrome is a result of the atrophy in the structures of the diencephalon (the thalamus, hypothalamus and mammillary bodies), and is similar to amnesia that is presented as a result of other cases of damage to the medial temporal lobe.[25] It has been argued that the memory impairments can occur as a result of damage along any part of the mammillo-thalamic tract, which explains how WKS can develop in patients with damage exclusively to either the thalamus or the mammillary bodies.[24]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome is by clinical impression and can sometimes be confirmed by a formal neuropsychological assessment. Wernicke encephalopathy typically presents with ataxia and nystagmus, and Korsakoff's psychosis with anterograde and retrograde amnesia and confabulation upon relevant lines of questioning.[23]

Frequently, secondary to thiamine deficiency and subsequent cytotoxic edema in Wernicke encephalopathy, patients will have marked degeneration of the mammillary bodies. Thiamine (vitamin B1) is an essential coenzyme in carbohydrate metabolism and is also a regulator of osmotic gradient. Its deficiency may cause swelling of the intracellular space and local disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Brain tissue is very sensitive to changes in electrolytes and pressure and edema can be cytotoxic. In Wernicke this occurs specifically in the mammillary bodies, medial thalami, tectal plate, and periaqueductal areas. Sufferers may also exhibit a dislike for sunlight and so may wish to stay indoors with the lights off. The mechanism of this degeneration is unknown, but it supports the current neurological theory that the mammillary bodies play a role in various "memory circuits" within the brain. An example of a memory circuit is the Papez circuit.

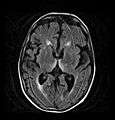

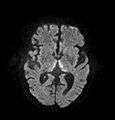

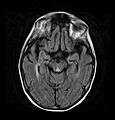

Axial MRI FLAIR image showing hyperintense signal in the mesial dorsal thalami, a common finding in Wernicke encephalopathy. This patient was nearly in coma when IV thiamine was started, he responded moderately well but was left with some Korsakoff type deficits.

Axial MRI FLAIR image showing hyperintense signal in the mesial dorsal thalami, a common finding in Wernicke encephalopathy. This patient was nearly in coma when IV thiamine was started, he responded moderately well but was left with some Korsakoff type deficits. Axial MRI B=1000 DWI image showing hyperintense signal indicative of restricted diffusion in the mesial dorsal thalami.

Axial MRI B=1000 DWI image showing hyperintense signal indicative of restricted diffusion in the mesial dorsal thalami. Axial MRI FLAIR image showing hyperintense signal in the periaqueductal gray matter and tectum of the dorsal midbrain.

Axial MRI FLAIR image showing hyperintense signal in the periaqueductal gray matter and tectum of the dorsal midbrain.

Prevention

As described, alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome usually follows or accompanies Wernicke encephalopathy. If treated quickly, it may be possible to prevent the development of AKS with thiamine treatments. This treatment is not guaranteed to be effective and the thiamine needs to be administered adequately in both dose and duration. A study on Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome showed that with consistent thiamine treatment there were noticeable improvements in mental status after only 2–3 weeks of therapy.[5] Thus, there is hope that with treatment Wernicke encephalopathy will not necessarily progress to WKS.

In order to reduce the risk of developing WKS it is important to limit the intake of alcohol in order to ensure that proper nutrition needs are met. A healthy diet is imperative for proper nutrition which, in combination with thiamine supplements, may reduce the chance of developing WKS. This prevention method may specifically help heavy drinkers who refuse to or are unable to quit.[1]

A number of proposals have been put forth to fortify alcoholic beverages with thiamine to reduce the incidence of WKS among those heavily abusing alcohol. To date, no such proposals have been enacted.[26][27][28][29][30]

Daily recommendations of thiamine requirements are 0.66 mg/2,000kcal daily or 1.2 mg for adult men and 1.1 mg for adult women per day.[31]

Treatment

The onset of Wernicke encephalopathy is considered a medical emergency, and thus thiamine administration should be initiated immediately when the disease is suspected.[5] Prompt administration of thiamine to patients with Wernicke encephalopathy can prevent the disorder from developing into Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, or reduce its severity. Treatment can also reduce the progression of the deficits caused by WKS, but will not completely reverse existing deficits. WKS will continue to be present, at least partially, in 80% of patients.[32] Patients suffering from WE should be given a minimum dose of 500 mg of thiamine hydrochloride, delivered by infusion over a 30-minute period for two to three days. If no response is seen then treatment should be discontinued but for those patients that do respond, treatment should be continued with a 250 mg dose delivered intravenously or intramuscularly for three to five days unless the patient stops improving. Such prompt administration of thiamine may be a life-saving measure.[5] Banana bags, a bag of intravenous fluids containing vitamins and minerals, is one means of treatment.[33][34]

Epidemiology

WKS occurs more frequently in men than women and has the highest prevalence in the ages 55–65. Approximately 71% are unmarried.[3]

Internationally, the prevalence rates of WKS are relatively standard, being anywhere between zero and two percent. Despite this, specific sub-populations seem to have higher prevalence rates including people who are homeless, older individuals (especially those living alone or in isolation), and psychiatric inpatients.[35] Additionally, studies show that prevalence is not connected to alcohol consumption per capita. For example, in France, a country that is well known for its consumption and production of wine, prevalence was only 0.4% in 1994, while Australia had a prevalence of 2.8%.[36]

History

Wernicke encephalopathy

Carl Wernicke discovered Wernicke encephalopathy in 1881. His first diagnosis noted symptoms including paralyzed eye movements, ataxia, and mental confusion. Also noticed were hemorrhages in the gray matter around the third and fourth ventricles and the cerebral aqueduct. Brain atrophy was only found upon post-mortem autopsy. Wernicke believed these hemorrhages were due to inflammation and thus the disease was named polioencephalitis haemorrhagica superior. Later, it was found that Wernicke encephalopathy and alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome are products of the same cause.[35]

Alcoholic Korsakoff syndrome

Sergei Korsakoff was a Russian physician after whom the disease "Korsakoff's syndrome" was named. In the late 1800s Korsakoff was studying long-term alcoholic patients and began to notice a decline in their memory function.[35] At the 13th International Medical Congress in Moscow in 1897, Korsakoff presented a report called: "On a special form of mental illness combined with degenerative polyneuritis". After the presentation of this report the term "Korsakoff's syndrome" was coined.[24]

Although WE and AKS were discovered separately, these two syndromes are usually referred to under one name, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, due to the fact that they are part of the same cause and because the onset of AKS usually follows WE if left untreated.

Society and culture

The British neurologist Oliver Sacks describes case histories of some of his patients with the syndrome in the book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985).

See also

- Alcoholic dementia

- Dementia

- Malabsorption

References

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome

- Thomson, Allan D.; Marshall, E. Jane (2006). "The natural history and pathophysiology of Wernicke's Encephalopathy and Korsakoff's Psychosis". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 41 (2): 151–8. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh249. PMID 16384871.

- Dam, Mirjam Johanna; Meijel, Berno; Postma, Albert; Oudman, Erik (2020-01-15). "Health problems and care needs in patients with Korsakoff's syndrome: A systematic review". Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: jpm.12587. doi:10.1111/jpm.12587. ISSN 1351-0126. PMID 31876326.

- Vetreno, Ryan Peter (2011). Thiamine deficiency-induced neurodegeneration and neurogenesis (PhD Thesis). Binghamton University. ISBN 978-1-124-75696-7. OCLC 781626781.

- Sechi, GianPietro; Serra, Alessandro (2007). "Wernicke's encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management". The Lancet Neurology. 6 (5): 442–55. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70104-7. PMID 17434099.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. OCLC 830807378.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ingram, V.; Kelly, M.; Grammer, G. "Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome Following Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for Sleep Apnea". in "Abstracts Presented at the Thirty-First Annual International Neuropsychological Society Conference, February 5–8, 2003 Honolulu, Hawaii". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 9 (2): 135–330. 2003. doi:10.1017/S1355617703920017.

- Thomson, Allan D.; Cook, Christopher C. H.; Guerrini, Irene; Sheedy, Donna; Harper, Clive; Marshall, E. Jane (2008). "Review: Wernicke encephalopathy revisited: Translation of the case history section of the original manuscript by Carl Wernicke 'Lehrbuch der Gehirnkrankheiten fur Aerzte and Studirende' (1881) with a commentary". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 43 (2): 174–9. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agm144. PMID 18056751.

- Brand, Matthias; Fujiwara, Esther; Kalbe, Elke; Steingass, Hans-Peter; Kessler, Josef; Markowitsch, Hans J. (2003). "Cognitive Estimation and Affective Judgments in Alcoholic Korsakoff Patients". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 25 (3): 324–34. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.327.3291. doi:10.1076/jcen.25.3.324.13802. PMID 12916646.

- Kopelman, M. D.; Thomson, A. D.; Guerrini, I.; Marshall, E. J. (2009). "The Korsakoff Syndrome: Clinical Aspects, Psychology and Treatment". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 44 (2): 148–54. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn118. PMID 19151162.

- Oscar-Berman, Marlene; Pulaski, Joan L. (1997). "Associative learning and recognition memory in alcoholic Korsakoff patients". Neuropsychology. 11 (2): 282–9. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.11.2.282. PMID 9110334.

- Kessels, Roy P. C.; Kortrijk, Hans E.; Wester, Arie J.; Nys, Gudrun M. S. (2008). "Confabulation behavior and false memories in Korsakoff's syndrome: Role of source memory and executive functioning". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 62 (2): 220–5. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01758.x. PMID 18412846.

- Osiezagha, Kenneth; Ali, Shahid; Freeman, C.; Barker, Narviar C.; Jabeen, Shagufta; Maitra, Sarbani; Olagbemiro, Yetunde; Richie, William; Bailey, Rahn K. (2013). "Thiamine Deficiency and Delirium". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 10 (4): 26–32. ISSN 2158-8333. PMC 3659035. PMID 23696956.

- Zimitat, Craig; Nixon, Peter F. (1999). "Glucose loading precipitates acute encephalopathy in thiamin-deficient rats". Metabolic Brain Disease. 14 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1023/A:1020653312697. PMID 10348310.

- Navarro, Darren; Zwingmann, Claudia; Chatauret, Nicolas; Butterworth, Roger F. (2008). "Glucose loading precipitates focal lactic acidosis in the vulnerable medial thalamus of thiamine-deficient rats". Metabolic Brain Disease. 23 (1): 115–22. doi:10.1007/s11011-007-9076-z. PMID 18034292.

- Watson, A. J. S.; Walker, J. F.; Tomkin, G. H.; Finn, M. M. R.; Keogh, J. A. B. (1981). "Acute Wernickes Encephalopathy precipitated by glucose loading". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 150 (10): 301–3. doi:10.1007/BF02938260. PMID 7319764.

- Mann, Karl; Agartz, Ingrid; Harper, Clive; Shoaf, Susan; Rawlings, Robert R.; Momenan, Reza; Hommer, Daniel W.; Pfefferbaum, Adolf; Sullivan, Edith V.; Anton, Raymond F.; Drobes, David J.; George, Mark S.; Bares, Roland; Machulla, Hans-Juergen; Mundle, Goetz; Reimold, Matthias; Heinz, Andreas (2001). "Neuroimaging in Alcoholism: Ethanol and Brain Damage". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25 (5 Suppl ISBRA): 104S–109S. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02383.x. PMID 11391058.

- Butterworth, RF (1993). "Pathophysiology of cerebellar dysfunction in the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 20 Suppl 3: S123–6. PMID 8334588. INIST:4778798.

- Nixon, Peter F.; Kaczmarek, M. Jan; Tate, Jill; Kerr, Ray A.; Price, John (1984). "An erythrocyte transketolase isoenzyme pattern associated with the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 14 (4): 278–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.1984.tb01181.x. PMID 6434322.

- Shimomura, Tatsuo; Mori, Etsuro; Hirono, Nobutsugu; Imamura, Toru; Yamashita, Hikari (1998). "Development of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome after long intervals following gastrectomy". Archives of Neurology. 55 (9): 1242–5. doi:10.1001/archneur.55.9.1242. PMID 9740119.

- Todd, Kathryn G.; Hazell, Alan S.; Butterworth, Roger F. (1999). "Alcohol-thiamine interactions: an update on the pathogenesis of Wernicke encephalopathy". Addiction Biology. 4 (3): 261–72. doi:10.1080/13556219971470. PMID 20575793.

- He, Xiaohua; Sullivan, Edith V; Stankovic, Roger K; Harper, Clive G; Pfefferbaum, Adolf (2007). "Interaction of Thiamine Deficiency and Voluntary Alcohol Consumption Disrupts Rat Corpus Callosum Ultrastructure". Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (10): 2207–16. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301332. PMID 17299515.

- Martin, Peter R.; Singleton, Charles K.; Hiller-Sturmhöfel, Susanne (2003). "The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease". Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 27 (2): 134–142. ISSN 1535-7414. PMC 6668887. PMID 15303623.

- Kyoko Konishi. (2009) The Cognitive Profile of Elderly Korsakoff's Syndrome Patients.

- Caulo, M. (2005). "Functional MRI study of diencephalic amnesia in Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome". Brain. 128 (7): 1584–94. doi:10.1093/brain/awh496. PMID 15817513.

- Kamien, Max (19 June 2006). "The repeating history of objections to the fortification of bread and alcohol: from iron filings to folic acid". The Medical Journal of Australia. 184 (12): 638–640. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00422.x. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Centerwall, Brandon (12 February 1979). "Put Thiamine in Liquor". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Binns, Colin W.; Carruthers, Susan J.; Howat, Peter A. (September 1989). "Thiamin in beer: a health promotion perspective". Community Health Studies. XIII (3): 301–5. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.1989.tb00210.x. PMID 2605903.

- Meikle, James (18 November 2002). "A pint of best and be generous with the B1, please landlord". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Finlay-Jones, Robert (1986). "Should Thiamine Be Added to Beer?". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 20 (1): 3–6. doi:10.3109/00048678609158858. PMID 3460583.

- Osiezagha, Kenneth; Ali, Shahid; Freeman, C.; Barker, Narviar C.; Jabeen, Shagufta; Maitra, Sarbani; Olagbemiro, Yetunde; Richie, William; Bailey, Rahn K. (April 2013). "Thiamine Deficiency and Delirium". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 10 (4): 26–32. ISSN 2158-8333. PMC 3659035. PMID 23696956.

- Victor, M; Adams, RD; Collins, GH (1971). "The Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. A clinical and pathological study of 245 patients, 82 with post-mortem examinations". Contemporary Neurology Series. 7: 1–206. PMID 5162155.

- Jeffrey E Kelsey; D Jeffrey Newport & Charles B Nemeroff (2006). "Alcohol Use Disorders". Principles of Psychopharmacology for Mental Health Professionals. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-471-79462-2.

- Merle A. Carter & Edward Bernstein (2005). "Acute and Chronic Alcohol Intoxication". In Elizabeth Mitchell & Ron Medzon (eds.). Introduction to Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7817-3200-0.

- Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome at eMedicine

- Harper, Clive; Fornes, Paul; Duyckaerts, Charles; Lecomte, Dominique; Hauw, Jean-Jacques (1995). "An international perspective on the prevalence of the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome". Metabolic Brain Disease. 10 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1007/BF01991779. PMID 7596325.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |