Përmet

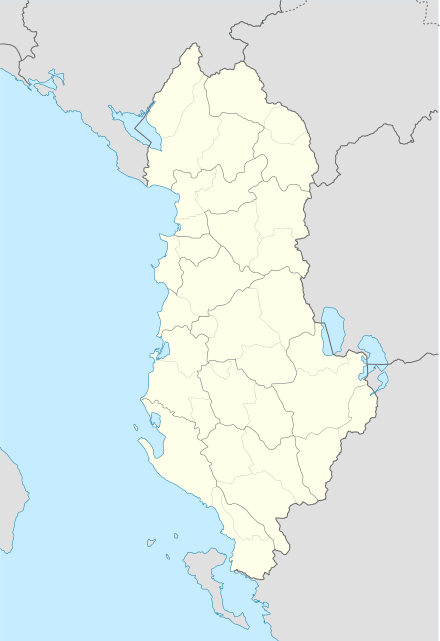

Përmet is a town and a municipality in Gjirokastër County, southern Albania. It was formed at the 2015 local government reform by the merger of the former municipalities Çarçovë, Frashër, Përmet, Petran and Qendër Piskovë, that became municipal units. The seat of the municipality is the town Përmet.[1] The total population is 10,614 (2011 census),[2] in a total area of 602.47 km2.[3] The population of the former municipality at the 2011 census was 5,945.[2] It is flanked by the Vjosë river, which runs along the Trebeshinë-Dhëmbel-Nemërçkë mountain chain, between Trebeshinë and Dhëmbel mountains, and through the Këlcyrë Gorge.

Përmet | |

|---|---|

Katiu Bridge | |

Emblem | |

| Nickname(s): City of Flowers | |

Përmet | |

| Coordinates: 40°14′N 20°21′E | |

| Country | |

| County | Gjirokastër |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alma Hoxha (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 602.47 km2 (232.61 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 246 m (807 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Municipality | 10,614 |

| • Municipality density | 18/km2 (46/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 5,945 |

| Demonym(s) | Përmetar/e |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal Code | 6401 |

| Area Code | (0)813 |

| Website | Official Website |

Name

The town itself is known in Albanian as Përmet, and definite Albanian form: Përmeti when in definite form. The town is known in Aromanian as Părmeti,[4] in Greek as Πρεμετή/Premeti[5][6] and in Turkish as Permedi.[7]

History

15th century

In 15th century Përmet came under Ottoman rule and became first a kaza of the sanjak of Gjirokastër and later of the Sanjak of Ioannina.[8][9]

18th century

During the era of conversions to Islam in the 18th century, Christian Albanian speaking areas such as the region of Rrëzë strongly resisted those efforts, in particular the village of Hormovë and the town of Përmet.[10]

In 1778, a Greek school was established and financed by the local Orthodox Church and the diaspora of the town.[11]

19th century

After a successful revolt in 1833 the Ottoman Empire replaced Ottoman officials in the town with local Albanian ones and proclaimed a general amnesty for all those who had been involved in the uprising.[12] The artisans of the kaza of Përmet held the monopoly in the trade of opinga in the vilayets of Shkodër and Janina until 1841, when that privilege was revoked under the Tanzimat reforms.[13] In 1882 Greek education was expanded with the foundation of a Greek girls' school subsidized by members of the local diaspora that lived in Constantinople, as well as the Greek national benefactor, Konstantinos Zappas.[11] The first Albanian-language school of the town was founded in the beginning of 1890 by Llukë Papavrami, a teacher from Hotovë, who had the endorsement of Naim Frasheri.[14][15] A great contribution for the Albanian school was given by philanthropists Mihal Kerbici,Pano Duro and Stathaq Duka. Duro and Kerbici financed until 1896 the salaries of five teachers, whereas Stathaq Duka bequeathed in 1886 scholarships for studies in the schools of Jurisprudence and Medicine.[15] In 1909 during the Second Constitutional Era the authorities allowed Albanian language to be taught in the local madrasah.[16] In 1919, Përmet had 40 Greek schools, 45 Greek teachers, and 1,189 Greek scholars.[17] It was a kaza centre as "Premedi" in Ergiri sanjak of Yanya Vilayet till 1912.

20th century

In 1912, during the First Balkan War the population founded a committee that had as its goal the organization of the local resistance with help from government of Vlora and chetas operating across Southern Albania. In a 28 December rally through the town centre people of Permet agreed they must fight where the nation most needed.[18] In February 1913, units of the advancing 3rd Division of the Greek Army entered the town without facing Ottoman resistance,[19] while the resistance of the local population was not sufficient due to small amount of arms.[18] In 1914, Përmet became part of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, which struggled against annexation of the region to the Albanian state.[20] During the Greco-Italian War, on December 4, 1940, the town came under the control of the advancing forces of the Greek II Army Corps.[21] Përmet returned to Axis control in April 1941. In May 1944 the National Liberation Movement held in the town the congress, which elected the provisional government of Albania.[22] During the Communist era Përmet held the title of the Hero City.

In August 2013, demonstrations took place[23] by the local Orthodox community as a result of the confiscation of the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin and the forcible removal of the clergy and of religious artifacts from the temple, by the state authorities.[24][25] The Cathedral was allegedly not fully returned to the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania after the restoration of Democracy in the country.[26] The incident provoked reactions by the Orthodox Church of Albania and also trigerred diplomatic intervention from Greece.[25][27]

Demographics

The total population is 10,614 (2011 census). The population of the former municipality at the 2011 census was 5,945.[2]

Demographic history

- 1913: Under Greek occupation, for the purpose of convincing the Congress of London of Greek expansionist claims, the Greek authorities took a census; however the census did not inquire about ethnicity, but rather instead explicitly had all Christians renamed "Greeks" and all Muslims changed to "Albanians", by religious criteria alone. The Greek considered Orthodox Albanians, Vlachs and Slav-speakers of the South as ethnically Greeks[28] According to the "Ethnographical map of Northern Epirus" which was written in the period of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, the town had a population of 2.824 inhabitants, of which 1.529 were ethnic Albanians and the rest 1.295 were Greeks.[29]

- 1930: Përmet had 1,000 houses of which 300 were shops and it was the main centre of trade in the region.[30] Its population was Muslim.[30]

Culture

Përmet is known for its cuisine, particularly the many different types of jam (reçel) and kompot (komposto), and the production of local wine and raki.[31]

Notable Landmarks

- Guri i Qytetit

- Katiu Bridge

Sports

Përmet is also home to the football club SK Përmeti and basketball club KB Përmeti.

Mayors

| No. | Name | Term in office | |

| 1 | Dhimitër Nasi | 1992 | 1996 |

| 2 | Spartak Kondi | 1996 | 2000 |

| 3 | Ani Kote | 2000 | 2003 |

| 4 | Petrit Bregasi | 2003 | 2007 |

| 5 | Edmond Komino | 2007 | 2011 |

| 6 | Gilberto Jace | 2011 | 2015 |

| 7 | Niko Shupuli | 2015 | Incumbent |

Notable people

- Laver Bariu, clarinetist

- Stefanaq Pollo, historian

- Adam Doukas, (1790-1860), Greek revolutionary and Minister of War.

- Vasileios Ioannidis, Greek theologian and professor

- Antoneta Papapavli, actress

- Odhise Paskali, sculptor People's Artist of Albania

- Turhan Përmeti, politician and former Prime Minister of Albania

- Simon Stefani, politician

- Mentor Xhemali, singer

- Hasan Bejo, Title Honorary Citizen (Kelcyre - Permet), [[as a historical figure of the Permet region. For bravery as a freedom fighter in World War II for the liberation of the homeland. A high-ranking military man, educated in Rome and Warsaw, an authority with great moral influence for the province of Deshnica in Këlcyrë and throughout the Përmet region, cultivated the values of the community through the history of the village of Toshkez, Këlcyre. Mr. Bejo was a high figure in the whole region of Përmet and for the Bejo family. Large noble family with historical tradition, very wide friendly ties, positive impact on the whole social life of the area and the province. Important contributor through the professional military tradition prominent in the consolidation of the Albanian state. The Bejo family is also represented by well-known figures such as; military, writers, bankers, lawyers, artists, farmers and founders of the first albanological chair of Albanian language and culture at De Paul University in Chicago, USA]].

See also

- Fir of Hotova National Park

- List of mayors of Përmet

- Music of Albania

- Tourism in Albania

- Vjosa River

References

- Law nr. 115/2014 Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Population and housing census - Gjirokastër 2011" (PDF). INSTAT. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "Correspondence table LAU – NUTS 2016, EU-28 and EFTA / available Candidate Countries" (XLS). Eurostat. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- Kahl, Thede (1999). Ethnizität und räumliche Verbreitung der Aromunen in Südosteuropa. Universität Münster: Institut für Geographie der Westfälischen Wilhelms. p. 144. ISBN 3-9803935-7-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "Părmeti"

- Eduardo D. Faingold (2010). The Kalamata Diary: Greece, War, and Emigration. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-7391-2890-9.

- Owen Pearson (11 July 2006). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume II: Albania in Occupation and War, 1939-45. I.B.Tauris. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-1-84511-104-5.

- Erdal, İbrahim (2006), Mübadele: uluslaşma sürecinde Türkiye ve Yunanistan 1923-1925, IQ Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık. p. 186. "Permedi".

- History of the Albanian people p. 85

- H. Karpat, Kemal (1985). Ottoman population, 1830–1914: demographic and social characteristics. p. 146. ISBN 9780299091606. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Gerogiorgi, Sofia (2002). "Επιγραφικές μαρτυρίες σε λειψανοθήκη από τη Βόρεια Ήπειρο". Δελτίον της Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας. 23: 79.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "Ιδιαίτερη εντύπωση προκαλεί η ισχυρή αντίσταση που προέβαλαν ορισμένες περιοχές στο έντονο κύμα εξισλαμισμών του 18ου αιώνα, όπως οι περιοχές της Ζαγοριάς (όπου υπάγεται η Κόνσκα και η Σέπερη), της Ρίζας (όπου υπάγεται το Χόρμοβο και η Πρεμετή) και της Λιντζουριάς, μολονότι κατοικούνταν από αλβανόφωνους χριστιανούς."

- Koltsida, Athina. Η Εκπαίδευση στη Βόρεια Ήπειρο κατά την Ύστερη Περίοδο της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας (PDF) (in Greek). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki: 131, 214, 406. Retrieved 7 June 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Stefanaq Pollo (1983). Historia e Shqipërisë: Vitet 30 të shek. XIX-1912. Akademia e Shkencave e RPS të Shqipërisë, Instituti i Historisë. p. 85.

Shtrirja e gjerë e kryengritjes, që fillonte nga Skrapari e Kurveleshi, në Myzeqe e në Vlorë e deri në Çamëri, e detyruan Portën e Lartë të hiqte dorë nga rekrutimi i ushtarëve nizamë, të shpallte amnistinë dhe të lejonte vendosjen e disa shqiptarëve si qeveritarë në kazatë e Beratit, të Vlorës, të Tepelenës, të Gjirokastrës e të Përmetit dhe emërimin e të tjerëve si komandantë në garnizonet e kështjellave të Beratit, të Gjirokastrës etj.

- History of the Albanian people pp. 45–6

- [Qemal Haxhihasani, “Kërkime dhe Vëzhgime Folklorike në rrethin e Përmetit”, Buletin I Universitetit Shtetëror të Tiranës seria Shkencat Shoqërore Nr. 2, V. 1959 f. 121.]

- Nuri Dragoj TREVA E PËRMETIT NË PERIUDHËN E VITEVE 1912-1944 pXIII

- Academy of Sciences of Albania, History of the Albanian people p.401

- Pan-Epirotic Union in America, Boston (1919). Statement of the Natives of Korytsa and Kolonia. p. 20.

Premeti has 40 Greek schools, 45 Greek teachers, and 1,189 Greek scholars.

- Nuri Dragoj (2015). Përmeti nga lufta për pavarësi ne pushtimin grek: (Veprimtari atdhetare dhe politike) (in Albanian). Toena. pp. 5–7.

- ...], Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate. [Ed. committee: Dimitrios Gedeon (1998). A concise history of the Balkan Wars, 1912-1913 (1.udg. ed.). Athens: Hellenic Army General Staff. p. 201. ISBN 9789607897077.

On 22 February, Division III moved from Korytsa towards Premeti, by way of Leskovik, meeting no Turkish resistance.

CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Kondis, Basil (1976). Greece and Albania: 1908-1914. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies, New York University. p. 125.

Besides Argyrokastro, the Autonomous North Epirus included the towns of Chimara, Delvino, Santi Quaranta, and Premeti

- John Carr. The Defence and Fall of Greece 1940-1941, p. 90

- Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 155. ISBN 9781860645419.

- Barkas, Panagiotis. "Violent Clashes against Clergy and Faithful in Permet". skai.gr. Athens News Agency. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "International Religious Freedom Report for 2014: Albania" (PDF). https://www.state.gov/. United States, Department of State. p. 4. Retrieved 20 October 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - Diamadis, Panayiotis (Spring 2014). "Clash of Eagles with Two Heads: Epirus in the 21st Century" (PDF). American Hellenic Institute Foundation Policy Journal: 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

Clergy and faithful were violently ejected from an Orthodox church in Premeti during the celebrations for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary on 16 August 2013, by private security and municipal authorities. Religious items such as icons and utensils were also confiscated.

- Watch, Human Rights; [Researched, Helsinki.; Abrahams], written by Fred (1996). Human rights in post-communist Albania. New York [u.a.]: Human Rights Watch. p. 157. ISBN 9781564321602.

A further point of contention between the Albanian Orthodox Church and the Albanian government is the return of church property.... In addition many holy icons and vessels of the Orthodox Church are being held in national museums, allegedly because of the Albanian government is concerned with protecting these valuable objects.... other church property that have been allegedly not been fully returned by the state include, the Cathedral of the Assumption in Permet

- "Conflict in Permet about the Church, police takes control of the House of Culture". Independent Balkan News Agency. August 28, 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Psomas, Lambros (2008). The Religious and Ethnic Synthesis of Southern Albania (Northern Epirus). Page 253: "The Greeks supported their claims Southern Albania or Northern Epirus, as they call it, based some statistics that they produced. They followed the same policy in the Conference of the Ambassadors in London 1913 (Table 2.2) and the Peace Conference of Paris 1919 as well... The Greeks argued that southern Albania should be yielded to them for specific historical and geographical They also supported that the inhabitants of the South were Greeks by sentiment. This argument of the sentiment was based the common religion between the Greeks and the Orthodox population of the South. As a result, the Greeks considered a11 Orthodox Albanian, Vlach and Slav-speaking people of the South as ethnically Greeks... Explicitly, the terms Orthodox Christian and Muslim were changed into Greek and Albanian respectively."

- Hellenic Army General Staff, Χάρτης Εθνογραφικός της Βορείου Ηπείρου τω 1913. Εθνολογική στατιστική της Βορείου Ηπείρου τω 1913 [Ethnographical map of Northern Epirus in 1913. Ethnographical statistics of Northern Epirus in 1913], Τύποις "Άγκυρας" - Ι. Κουμένου, Thessaloniki 1919, p. 16

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780198142539.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "The main centre of trade is Permet, where there is a bridge over the Vjosë. The town had about 1,000 houses in 1930, and 300 of these were shops. A crag in the town is said to be an ancient site. I climbed up into it. There are ruins of some medieval houses and the remains of a church on top, but the rock is not cut or levelled at all. While Permet is Mohammedan, the village to the west on the slopes of Mt. Nemerçkë are Christian."

- Gillian Gloyer (7 January 2015). Albania. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-84162-855-4.

Sources

- Blocal, Giulia (5 October 2014). "Përmet and the Balkan side of Albania". Blocal Travel blog.

- History of the Albanian people II 1830–1912. Academy of Sciences of Albania. 2002.

External links

- Visit Permet Official Tourism Portal

- Vjosa/Aoos River Ecomuseum Official Website