Silver iodide

Silver iodide is an inorganic compound with the formula AgI. The compound is a bright yellow solid, but samples almost always contain impurities of metallic silver that give a gray coloration. The silver contamination arises because AgI is highly photosensitive. This property is exploited in silver-based photography. Silver iodide is also used as an antiseptic and in cloud seeding.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Silver(I) iodide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.125 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| AgI | |

| Molar mass | 234.77 g/mol |

| Appearance | yellow, crystalline solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 5.675 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 558 °C (1,036 °F; 831 K) |

| Boiling point | 1,506 °C (2,743 °F; 1,779 K) |

| 3×10−7g/100mL (20 °C) | |

Solubility product (Ksp) |

8.52 × 10 −17 |

| −80.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| hexagonal (β-phase, < 147 °C) cubic (α-phase, > 147 °C) | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar entropy (S |

115 J·mol−1·K−1[1] |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−62 kJ·mol−1[1] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | Sigma-Aldrich |

EU classification (DSD) (outdated) |

not listed |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

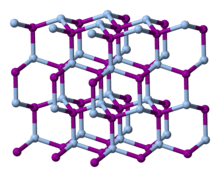

Structure

The structure adopted by silver iodide is temperature dependent:[2]

- Below 420 K, the β phase of AgI, with the wurtzite structure, is most stable. This phase is encountered in nature as the mineral iodargyrite.

- Above 420 K, the α phase becomes more stable. This motif is a body-centered cubic structure which has the silver centers distributed randomly between 6 octahedral, 12 tetrahedral and 24 trigonal sites.[3] At this temperature, Ag+ ions can move rapidly through the solid, allowing fast ion conduction. The transition between the β and α forms represents the melting of the silver (cation) sublattice. The entropy of fusion for α-AgI is approximately half that for sodium chloride (a typical ionic solid). This can be rationalized by considering the AgI crystalline lattice to have already "partly melted" in the transition between α and β polymorphs.

- A metastable γ phase also exists below 420 K with the zinc blende structure.

Preparation and properties

Silver iodide is prepared by reaction of an iodide solution (e.g., potassium iodide) with a solution of silver ions (e.g., silver nitrate). A yellowish solid quickly precipitates. The solid is a mixture of the two principal phases. Dissolution of the AgI in hydroiodic acid, followed by dilution with water precipitates β-AgI. Alternatively, dissolution of AgI in a solution of concentrated silver nitrate followed by dilution affords α-AgI.[4] If the preparation is not conducted in the absence of sunlight, the solid darkens rapidly, the light causing the reduction of ionic silver to metallic. The photosensitivity varies with sample purity.

Cloud seeding

The crystalline structure of β-AgI is similar to that of ice, allowing it to induce freezing by the process known as heterogeneous nucleation. Approximately 50,000 kg are used for cloud seeding annually, each seeding experiment consuming 10–50 grams.[5] (see also Project Stormfury)

Safety

Extreme exposure can lead to argyria, characterized by localized discoloration of body tissue.[6]

References

- Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- Binner, J. G. P.; Dimitrakis, G.; Price, D. M.; Reading, M.; Vaidhyanathan, B. (2006). "Hysteresis in the β–α Phase Transition in Silver Iodine" (PDF). Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 84 (2): 409–412. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.368.2816. doi:10.1007/s10973-005-7154-1.

- Hull, Stephen (2007). "Superionics: crystal structures and conduction processes". Rep. Prog. Phys. 67 (7): 1233–1314. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/67/7/R05.

- O. Glemser, H. Saur "Silver Iodide" in Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1036-7.

- Phyllis A. Lyday "Iodine and Iodine Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_381

- "Silver Iodide". TOXNET: Toxicogy Data Network. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silver iodide. |