Admiralty

The Admiralty, originally known as the Office of the Admiralty and Marine Affairs,[1] was the government department[2][3] responsible for the command of the Royal Navy first in the Kingdom of England, later in the Kingdom of Great Britain, and from 1801 to 1964,[4] the United Kingdom and former British Empire. Originally exercised by a single person, the Lord High Admiral (1385–1628), the Admiralty was, from the early 18th century onwards, almost invariably put "in commission" and exercised by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, who sat on the Board of Admiralty.

.svg.png) Coat of Arms of Her Majesty's Government | |

| Department overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1707 |

| Preceding Department |

|

| Dissolved | 1964 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | Government of the United Kingdom |

| Headquarters | War Office building Whitehall London |

| Department executive | |

| Parent Department | HM Government |

In 1964, the functions of the Admiralty were transferred to a new Admiralty Board, which is a committee of the tri-service Defence Council of the United Kingdom and part of the Navy Department[5] of the Ministry of Defence. The new Admiralty Board meets only twice a year, and the day-to-day running of the Royal Navy is controlled by a Navy Board (not to be confused with the historic Navy Board described later in this article). It is common for the various authorities now in charge of the Royal Navy to be referred to as simply 'The Admiralty'.

The title of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom was vested in the monarch from 1964 to 2011. The title was awarded to Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh by Queen Elizabeth II on his 90th birthday.[6] There also continues to be a Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom and a Rear-Admiral of the United Kingdom, both of which are honorary offices.

History

The office of Admiral of England (later Lord Admiral, and later Lord High Admiral) was created around 1400; there had previously been Admirals of the northern and western seas. King Henry VIII established the Council of the Marine—later to become the Navy Board—in 1546, to oversee administrative affairs of the naval service. Operational control of the Royal Navy remained the responsibility of the Lord High Admiral, who was one of the nine Great Officers of State. This management approach would continue in force in the Royal Navy until 1832.

King Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission in 1628, and control of the Royal Navy passed to a committee in the form of the Board of Admiralty. The office of Lord High Admiral passed a number of times in and out of commission until 1709, after which the office was almost permanently in commission (the last Lord High Admiral being the future King William IV in the early 19th century).

In this organization a dual system operated the Lord High Admiral (from 1546) then Commissioners of the Admiralty (from 1628) exercised the function of general control (military administration) of the Navy and they were usually responsible for the conduct of any war, while the actual supply lines, support and services were managed by four principal officers, namely, the Treasurer, Comptroller, Surveyor and Clerk of the Acts, responsible individually for finance, supervision of accounts, Shipbuilding and maintenance of ships, and record of business. These principal officers came to be known as the Navy Board responsible for 'civil administration' of the navy, from 1546 to 1832.

This structure of administering the navy lasted for 285 years, however, the supply system was often inefficient and corrupt its deficiencies were due as much to its limitations of the times they operated in. The various functions within the Admiralty were not coordinated effectively and lacked inter-dependency with each other, with the result that in 1832, Sir James Graham abolished the Navy Board and merged its functions within those of the Board of Admiralty. At the time this had distinct advantages; however, it failed to retain the principle of distinctions between the Admiralty and supply, and a lot of bureaucracy followed with the merger.

In 1860 saw big growth in the development of technical crafts, the expansion of more admiralty branches that really began with age of steam that would have an enormous influence on the navy and naval thought. Between 1860 and 1908, there was no real study of strategy and of staff work conducted within the naval service; it was practically ignored. All the Navy's talent flowed to the great technical universities. This school of thought for the next 50 years was exclusively technically based. The first serious attempt to introduce a sole management body to administer the naval service manifested itself in the creation of the Admiralty Navy War Council in 1909.[7] It was believed by officials within the Admiralty at this time that the running of war was quite a simple matter for any flag officer who required no formal training. However, this mentality would be severely questioned with the advent of the Agadir crisis, when the Admiralty's war plans were heavily criticized.

Following this, a new advisory body called the Admiralty War Staff was then instituted in 1912, headed by the Chief of the War Staff who was responsible for administering three new sub-divisions responsible for operations, intelligence and mobilisation. The new War Staff had hardly found its feet and it continually struggled with the opposition to its existence by senior officers they were categorically opposed to a staff. The deficiencies of the system within this department of state could be seen in the conduct of the Dardanelles campaign. There were no mechanisms in place to answer the big strategic questions. A Trade Division was created in 1914. Sir John Jellicoe came to the Admiralty in 1916. He re-organized the war staff as following: Chief of War Staff, Operations, Intelligence, Signal Section, Mobilisation, Trade.

It was not until 1917 that the admiralty department was again properly reorganized and began to function as a professional military staff. In May 1917, the term "Admiralty War Staff" was renamed and that department and its functional role were superseded by a new "Admiralty Naval Staff"; in addition, the newly created office of Chief of the Naval Staff was merged in the office of the First Sea Lord. Also appointed was a new post, that of Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, and an Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff; all were given seats on the Board of Admiralty. This for the first time gave the naval staff direct representation on the board; the presence of three senior naval senior members on the board ensured the necessary authority to carry through any operation of war. The Deputy Chief of Naval Staff would direct all operations and movements of the fleet, while the Assistant Chief of Naval Staff would be responsible for mercantile movements and anti-submarine operations.

The office of Controller would be re-established to deal with all questions relating to supply; on 6 September 1917, a Deputy First Sea Lord, was added to the Board who would administer operations abroad and deal with questions of foreign policy. In October 1917, the development of the staff was carried one step further by the creation of two sub-committees of the Board—the Operations Committee and the Maintenance Committee. The First Lord of the Admiralty was chairman of both committees, and the Operations Committee consisted of the First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff, the Deputy First Sea Lord, Assistant Chief of Naval Staff, and Fifth Sea Lord. The Maintenance Committee consisted of the Deputy First Sea Lord (representing the operations committee), Second Sea Lord (personnel), Third Sea Lord (materiel), Fourth Sea Lord (transport and stores), Civil Lord, Controller and Financial Secretary.

Full operational control of the Royal Navy was finally handed over to the Chief of Naval Staff (CNS) by an order in Council, effective October 1917, under which he became responsible for the issuing of orders affecting all war operations directly to the fleet. It also empowered the CNS to issue orders in their own name, as opposed to them previously being issued by the Permanent Secretary of the Admiralty in the name of the Board. In 1964, the Admiralty—along with the War Office and the Air Ministry—were abolished as separate departments of state, and placed under one single new Ministry of Defence. Within the expanded Ministry of Defence are the new Admiralty Board which has a separate Navy Board responsible for the day-to-day running of the Royal Navy, the Army Board and the Air Force Board, each headed by the Secretary of State for Defence. This structure remained in place until the department was abolished in 1964; the operational control and this system still remains in place with the Royal Navy today. For the organisational structure of the admiralty department and how it developed through the centuries see the following articles below.

Organizational structure

In the 20th century the structure of the Admiralty Headquarters was predominantly organized into four parts:[8]

- The Board of Admiralty, which directs and controls the whole machine chaired by a civilian government minister the First Lord of the Admiralty. His chief military adviser was the First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff as the Senior Naval Lord to the board.[8]

- The Admiralty Naval Staff, advised and assisted the Board in chief strategic and operational planning, in the distributing of fleets and the allocating of assets to major naval commands and stations and in formulating official policy on tactical doctrine and requirements in regard to men and material. In order to deliver this the Naval Staff was organised into specialist Divisions and Sections. When the Admiralty unified with the Ministry of Defence in 1964 they were re designated as Directorates of the Naval Staff.[8]

- The Admiralty Departments, which provides the men, ships, aircraft and supplies to carry out the approved policy. The departments are superintended by the various offices of the Sea Lords.[8]

- The Department of the Permanent Secretary which was the general co-ordinating agency, regulating naval finance, providing advice on policy, conducing all correspondence on behalf of the Board and maintaining admiralty records. Its primary component to deliver this is the Admiralty Secretariat, sections of the Secretariat (other than those which provide Common Services) were known as Branches.[8]

Board of Admiralty

When the office of Lord High Admiral was in commission, as it was for most of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, until it reverted to the Crown, it was exercised by a Board of Admiralty, officially known as the Commissioners for Exercising the Office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, &c. (alternatively of England, Great Britain or the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland depending on the period). The Board of Admiralty consisted of a number of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. The Lords Commissioners were always a mixture of admirals, known as Naval Lords or Sea Lords and Civil Lords, normally politicians. The quorum of the Board was two commissioners and a secretary. The president of the Board was known as the First Lord of the Admiralty, who was a member of the Cabinet. After 1806, the First Lord of the Admiralty was always a civilian, while the professional head of the navy came to be (and is still today) known as the First Sea Lord.[8]

Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty (1628–1964)

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty were the members of The Board of Admiralty, which exercised the office of Lord High Admiral when it was not vested in a single person. The commissioners were a mixture of politicians without naval experience and professional naval officers, the proportion of naval officers generally increasing over time.[8]

Key Officials

First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty was the British government's senior civilian adviser on all naval affairs and the minister responsible for the direction and control of the Admiralty and Marine Affairs Office later the Department of Admiralty.(+) His office was supported by the Naval Secretariat.[8]

First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff

The First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff was the Chief Naval Adviser on the Board of Admiralty to the First Lord and superintended the offices of the sea lords and the admiralty naval staff.[8]

Navy Board

The Navy Board was an independent board from 1546 until 1628 when it became subordinate to, yet autonomous of the Board of Admiralty until 1832. Its principal commissioners of the Navy advised the board in relation to civil administration of the naval affairs. The Navy Board was based at the Navy Office.

Board of Admiralty civilian members responsible other important civil functions

- Office of the Civil Lord of the Admiralty.[8]

- Office of the Additional Civil Lord of the Admiralty.[8]

- Office of the Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty.[8]

Admiralty Naval Staff

It evolved from *Admiralty Navy War Council, (1909–1912) which in turn became the Admiralty War Staff, (1912–1917) before finally becoming the Admiralty Naval Staff in 1917. It was the former senior command, operational planning, policy and strategy department within the British Admiralty. It was established in 1917 and existed until 1964 when the department of the Admiralty was abolished, and the staff departments function continued within the Navy Department of the Ministry of Defence until 1971 when its functions became part of the new Naval Staff, Navy Department of the Ministry of Defence.[9]

Offices of the Naval Staff

- Office of Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff.[8]

- Office of the Vice Chief of the Naval Staff.[8]

- Offices of the Assistant Chiefs of the Naval Staff.[8]

Admiralty Departments

The Admiralty Departments were distinct and component parts of the Department of Admiralty that were superintended by the various offices of the Sea Lords responsible for them; they were primarily administrative, research, scientific and logistical support organisations. The departments role was to provide the men, ships, aircraft and supplies to carry out the approved policy of the Board of Admiralty and conveyed to them during 20th century by the Admiralty Naval Staff.[8]

Offices of the Sea Lords

- Office of the Deputy First Sea Lord

- Office of the Second Sea Lord.[8]

- Office of the Third Sea Lord.[8]

- Office of the Fourth Sea Lord.[8]

- Office of Fifth Sea Lord

Department of the Permanent Secretary

The Secretary's Department consisted of members of the civil service it was directed and controlled by a senior civil servant Permanent Secretary to the Board of Admiralty he was not a Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty, he functioned as a member of the board, and attended all of its meetings.[8]

Organizational structure by time period

Admiralty Buildings

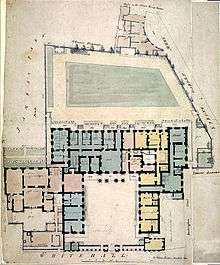

The Admiralty complex lies between Whitehall, Horse Guards Parade and The Mall and includes five inter-connected buildings. Since the Admiralty no longer exists as a department, these buildings are now used by separate government departments:

The Admiralty

The oldest building was long known simply as The Admiralty; it is now known officially as the Ripley Building, a three-storey U-shaped brick building designed by Thomas Ripley and completed in 1726. Alexander Pope implied the architecture is rather dull, lacking either the vigour of the baroque style, fading from fashion at the time, or the austere grandeur of the Palladian style just coming into vogue. It is mainly notable for being perhaps the first purpose-built office building in Great Britain. It contained the Admiralty board room, which is still used by the Admiralty, other state rooms, offices and apartments for the Lords of the Admiralty. Robert Adam designed the screen, which was added to the entrance front in 1788. The Ripley Building is currently occupied by the Department for International Development.

Old Admiralty (Ripley Building) in 1760 before addition of the Adam screen

Old Admiralty (Ripley Building) in 1760 before addition of the Adam screen Old Admiralty (Ripley Building) c. 1790 after addition of the Adam screen

Old Admiralty (Ripley Building) c. 1790 after addition of the Adam screen Old Admiralty (Ripley Building) c. 1830

Old Admiralty (Ripley Building) c. 1830

Admiralty House

Admiralty House is a moderately proportioned mansion to the south of the Ripley Building, built in the late 18th century as the residence of the First Lord of the Admiralty from 1788. It served that purpose until 1964. Winston Churchill was one of its occupants in 1911–1915 and 1939–1940. It lacks its own entrance from Whitehall and is entered through the Ripley Courtyard or Ripley Building. It is a three-storey building in yellow brick with neoclassical interiors. Its rear facade faces directly onto Horse Guards Parade. The architect was Samuel Pepys Cockerell. The ground floor comprises meeting rooms for the Cabinet Office and the upper floors are three ministerial residences.

Admiralty Extension

This is the largest of the Admiralty Buildings. It was begun in the late 19th century and redesigned while the construction was in progress to accommodate the extra offices needed by the naval arms race with the German Empire. It is a red brick building with white stone, detailing in the Queen Anne style with French influences. It has been used by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office from the 1960s to 2016. The Department for Education planned to move into the building in September 2017 following the Foreign and Commonwealth Office's decision to leave the building and consolidate its London staff into one building on King Charles Street. A change of contractor (BAM was replaced by Willmott Dixon) delayed consolidation of the Department for Education to autumn 2018.[10]

Admiralty Arch

Admiralty Arch is linked to the Old Admiralty Building by a bridge and is part of the ceremonial route from Trafalgar Square to Buckingham Palace. In 2012, HM Government sold the building on a 125-year lease for £60m for a proposed redevelopment into a Waldorf Astoria luxury hotel and four apartments.

The Admiralty Citadel

This is a squat, windowless World War II fortress north west of Horse Guards Parade, now covered in ivy. See Military citadels under London for further details.

"Admiralty" as a metonym for "sea power"

In some cases, the term admiralty is used in a wider sense, as meaning sea power or rule over the seas, rather than in strict reference to the institution exercising such power. For example, the well-known lines from Kipling's Song of the Dead:

If blood be the price of admiralty,

Lord God, we ha' paid in full![11]

See also

- Admiralty administration

- Admiralty chart

- Admiralty Peak

- Navy Department (Ministry of Defence)

- List of Lords High Admiral

- List of the First Lords of the Admiralty

- List of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty

- Lord High Admiral of Scotland

- St Boniface's Catholic College

References

- Knighton, C. S.; Loades, David; Loades, Professor of History David (29 April 2016). Elizabethan Naval Administration. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 9781317145035.

- Hamilton, C. I. (3 February 2011). The Making of the Modern Admiralty: British Naval Policy-Making, 1805–1927. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9781139496544.

- Defence, Ministry of (2004). The Government's expenditure plans 2004–05 to 2005–06. London: Stationery Office. p. 8. ISBN 9780101621229.

- Lawrence, Nicholas Blake, Richard (2005). The illustrated companion to Nelson's navy (Paperback ed.). Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. p. 8. ISBN 9780811732758.

- Archives, The National. "Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Correspondence and Papers". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. National Archives, 1660–1976, ADM 1. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "New title for Duke of Edinburgh as he turns 90, who remains the incumbent". BBC news. BBC. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- Kennedy, Paul (24 April 2014). The War Plans of the Great Powers (RLE The First World War): 1880–1914. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 9781317702528.

- Great Britain, Parliament, House of Commons (1959). "Admiralty Office". House of Commons Papers, Volume 5. London, England: HM Stationery Office. pp. 5–24.

- Stationery Office, H.M. (31 October 1967). The Navy List. Spink and Sons Ltd, London, England. pp. 524–532.

- "Willmott Dixon wins Old Admirality [sic] Building refurb". constructionenquirer.com.

- Kipling, Rudyard (2015). Stories and Poems. Oxford University Press. p. 471. ISBN 9780198723431.

Further reading

The Building

- Bradley, Simon, and Nikolaus Pevsner. London 6: Westminster (from the Buildings of England series). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-300-09595-3.

- C. Hussey, "Admiralty Building, Whitehall", Country Life, 17 and 24 November 1923, pp. 684–692, 718–726.

The Office

- Daniel A. Baugh, Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole (Princeton, 1965).

- Sir John Barrow, An Autobiographical Memoir of Sir John Barrow, Bart., Late of the Admiralty (London, 1847).

- John Ehrman, The Navy in the War of William III: Its State and Direction (Cambridge, 1953).

- C. I. Hamilton, The Making of the Modern Admiralty: British Naval Policy-Making 1805–1927 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- C. I. Hamilton, "Selections from the Phinn Committee of Inquiry of October–November 1853 into the State of the Office of Secretary to the Admiralty, in The Naval Miscellany, volume V, edited by N. A. M. Rodger, (London: Navy Records Society, London, 1984).

- C. S. Knighton, Pepys and the Navy (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2003).

- Christopher Lloyd, Mr Barrow of the Admiralty (London, 1970).

- Malcolm H. Murfett, The First Sea Lords: From Fisher to Mountbatten (Westport: Praeger, 1995).

- Lady Murray, The Making of a Civil Servant: Sir Oswyn Murray, Secretary of the Admiralty 1917–1936 (London, 1940).

- N.A.M. Rodger, The Admiralty (Lavenham, 1979)

- J.C. Sainty, Admiralty Officials, 1660–1870 (London, 1975)

- Sir Charles Walker, Thirty-Six Years at the Admiralty (London, 1933)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Admiralty, Royal Navy. |

- The Admiralty at the Survey of London online