Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of the United Kingdom is the sixth of the Great Officers of State (not to be confused with the Great Offices of State), ranking beneath the Lord Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable. The Lord Great Chamberlain has charge over the Palace of Westminster (though since the 1960s his personal authority has been limited to the royal apartments and Westminster Hall).

| Lord Great Chamberlain of the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) The Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom as used by HM Government | |

Office held jointly by:

The 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley exercises the office for ceremonial purposes and sits in the House of Lords. since 13 March 1990 | |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Formation | c. 1126 |

| First holder | Robert Malet |

| Salary | Unpaid |

The Lord Great Chamberlain also has a major part to play in royal coronations, having the right to dress the monarch on coronation day and to serve the monarch water before and after the coronation banquet, and also being involved in investing the monarch with the insignia of rule.[1]

On formal state occasions, he wears a distinctive scarlet court uniform and bears a gold key and a white stave as the insignia of his office.

Office holders

The position is a hereditary one, held since 1780 in gross. At any one time, a single person actually exercises the office of Lord Great Chamberlain. The various individuals who hold fractions of the Lord Great Chamberlainship are technically each Joint Hereditary Lord Great Chamberlain. The Joint Hereditary Lord Great Chamberlains are choosing one individual of the rank of a knight or higher to be the Deputy Lord Great Chamberlain.[2][3] Due to an agreement from 1912, the right to exercise the office for a given reign rotates proportionately between three families (of the then three joint office holders) to the fraction of the office held. For instance, the Marquesses of Cholmondeley hold one-half of the office, and may therefore exercise the office or appoint a deputy every alternate reign. Whenever one of the three shares of the 1912 agreement is split further, the joint heirs of this share have to agree among each other, who should be their deputy or any mechanism to determine who of them has the right to choose a deputy.

The office of Lord Great Chamberlain is distinct from the non-hereditary office of Lord Chamberlain of the Household, a position in the monarch's household. This office arose in the 14th century as a deputy of the Lord Great Chamberlain to fulfil the latter's duties in the Royal Household, but now they are quite distinct.

The House of Lords Act 1999 removed the automatic right of hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords, but the Act provided that a hereditary peer exercising the office of Lord Great Chamberlain (as well as the Earl Marshal) be exempt from such a rule, in order to perform ceremonial functions.

History of the office

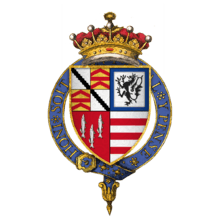

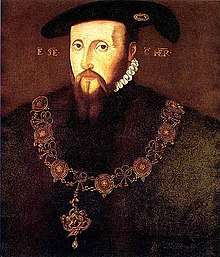

The office was originally held by Robert Malet, a son of one of the leading companions of William the Conqueror. In 1133, however, King Henry I declared Malet's estates and titles forfeit, and awarded the office of Lord Great Chamberlain to Aubrey de Vere, whose son was created Earl of Oxford. Thereafter, the Earls of Oxford held the title almost continuously until 1526, with a few intermissions due to the forfeiture of some Earls for treason. In 1526, however, the fourteenth Earl of Oxford died, leaving his aunts as his heirs. The earldom was inherited by a more distant heir-male, his second cousin. The Sovereign then decreed that the office belonged to The Crown, and was not transmitted along with the earldom. The Sovereign appointed the fifteenth Earl to the office, but the appointment was deemed for life and was not hereditary. The family's association with the office was interrupted in 1540, when the fifteenth earl died and Thomas Cromwell, the King's chief adviser, was appointed Lord Great Chamberlain.[4] After Cromwell's attainder and execution later the same year, the office passed through a few more court figures, until 1553, when it was passed back to the De Vere family, the sixteenth Earl of Oxford, again as an uninheritable life appointment.[5] Later, Queen Mary I ruled that the Earls of Oxford were indeed entitled to the office of Lord Great Chamberlain on an hereditary basis.

Thus, the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth Earls of Oxford held the position on a hereditary basis until 1626, when the eighteenth Earl died, again leaving a distant relative as heir male, but a closer one as a female heir. The House of Lords eventually ruled that the office belonged to the heir general, Robert Bertie, 14th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, who later became Earl of Lindsey. The office remained vested in the Earls of Lindsey, who later became Dukes of Ancaster and Kesteven. In 1779, however, the fourth Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven died, leaving two sisters as female heirs, and an uncle as an heir male. The uncle became the fifth and last Duke, but the House of Lords ruled that the two sisters were jointly Lord Great Chamberlain and could appoint a Deputy to fulfil the functions of the office. The barony of Willoughby de Eresby went into abeyance between the two sisters, but the Sovereign terminated the abeyance and granted the title to the elder sister, Priscilla Bertie, 21st Baroness Willoughby de Eresby. The younger sister later married the first Marquess of Cholmondeley. The office of Lord Great Chamberlain, however, was divided between Priscilla and her younger sister Georgiana. Priscilla's share was eventually split between two of her granddaughters, and has been split several more times since then. By contrast, Georgiana's share has been inherited by a single male heir each time; that individual has in each case been the Marquess of Cholmondeley, a title created for Georgiana's husband.

Twentieth century

In 1902 it was ruled by the house of Lords, that the joint office holders, the Earl of Ancaster, the Marquess of Cholmondeley and the Earl Carrington have to agree on a deputy to exercise the office, subject to the approval of the Sovereign. Otherwise the Sovereign should appoint a deputy until an agreement is reached.[6]

In 1912 an agreement was reached, that, alternating every reign, the right to appoint the person who exercises the office, rotates between the three joint office holders or respectively their heirs with the Marquess of Cholmondeley or his heirs, take turn every second reign.[7]

As the shares of the Marquess of Cholmondeley and the Earl of Ancaster are not further splitted, they decide in their turn who should or even act themselve as Lord Great Chamberlain. The share of the Earl of Carrington is widely spread and it is expected that on their turns his heirs will choose the current Lord Carrington, who is not even a shareholder of the office, to act as Lord Great Chamberlain.[8][9]

Lord Great Chamberlains, 1130–1779

Joint hereditary Lord Great Chamberlains, 1780–present

The fractions show the holder's share in the office, and the date they held it. The current (as of 2020) holders of the office are shown in bold face.

| Peregrine Bertie, 3rd Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Priscilla Bertie, 21st Baroness Willoughby de Eresby 1⁄2 1780–1828 | Georgiana Cholmondeley, Marchioness of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1780–1838 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

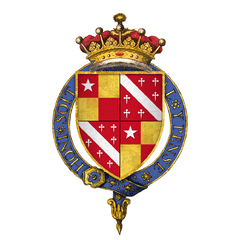

| Peter Drummond-Burrell, 22nd Baron Willoughby de Eresby 1⁄2 1828–1865 | George Cholmondeley, 2nd Marquess of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1838–1870 | William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1870–1884 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Albyric Drummond-Willoughby, 23rd Baron Willoughby de Eresby 1⁄2 1865–1870 | Clementina Drummond-Willoughby, 24th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby 1⁄4 1870–1888 | Charlotte Augusta Carrington, Lady Carrington 1⁄4 1870–1879 | Charles George Cholmondeley, Viscount Malpas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

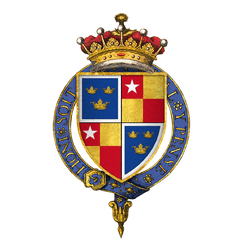

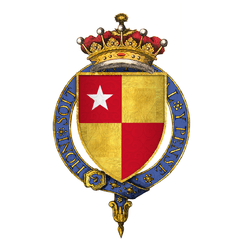

| Gilbert Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 1st Earl of Ancaster 1⁄4 1888–1910 | Charles Wynn-Carington, 1st Marquess of Lincolnshire 1⁄4 1879–1928 | George Cholmondeley, 4th Marquess of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1884–1923 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gilbert Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 2nd Earl of Ancaster 1⁄4 1910–1951 | Marjorie Wilson, Baroness Nunburnholme 1⁄20 1928–1968 | Lady Alexandra Llewellen Palmer 1⁄20 1928–1955 | Ruperta Legge, Countess of Dartmouth 1⁄20 1928–1963 | Judith Keppel, Countess of Albemarle | Lady Victoria Weld-Forester 1⁄20 1928–1966 | George Cholmondeley, 5th Marquess of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1923–1968 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| James Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 3rd Earl of Ancaster 1⁄4 1951–1983 | Charles Wilson, 3rd Baron Nunburnholme 1⁄20 1968–1974 | Brig. Anthony Llewellen Palmer 1⁄20 1955–1990 | Lady Mary Findlay 1⁄100 1963–2003 | Lady Elizabeth Basset 1⁄100 1963–2000 | Lady Diana Matthews 1⁄100 1963–1970 | Lady Barbara Kwiatkowska 1⁄100 1963–2013 | Josceline Chichester, Marchioness of Donegall 1⁄100 1963–1995 | Derek Keppel, Viscount Bury 1⁄20 1928–1968 | Sir Henry Legge-Bourke 1⁄20 1966–1973 | Hugh Cholmondeley, 6th Marquess of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1968–1990 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 28th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby 1⁄4 1983– | Ben Wilson, 4th Baron Nunburnholme 1⁄20 1974–1998 | Julian Llewellen Palmer 1⁄20 1990–2002 | Cdr Jonathan Findlay 1⁄100 2003–2015 | Bryan Basset 1⁄100 2000–2010 | Col James Gustavus Hamilton-Russell 1⁄100 1970– | Jan Witold Kwiatkowski 1⁄100 2013– | Patrick Chichester, 8th Marquess of Donegall 1⁄100 1995– | Rufus Keppel, 10th Earl of Albemarle 1⁄20 1968– | William Legge-Bourke 1⁄20 1973–2009 | David Cholmondeley, 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley 1⁄2 1990– | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Hon. Lorraine Wilson 1⁄80 1998– | The Hon. Tatiana Dent 1⁄80 1998– | The Hon. Ines Garton 1⁄80 1998– | The Hon. Ysabel Wilson 1⁄80 1998– | Nicholas Llewellen Palmer 1⁄20 2002– | Christopher Findlay 1⁄100 2015- | David Basset 1⁄100 2010 | Michael James Basset 1⁄100 2010– | Capt. Harry Russell Legge-Bourke 1⁄20 2009– | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Persons exercising the office of Lord Great Chamberlain, 1780–present

References

- Round, J. Horace (June 1902). "THE LORD GREAT CHAMBERLAIN". Monthly review. 7 (21): 42–58. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "House of Lords Journal Volume 36: May 1781 21-30". Journal of the House of Lords Volume 36, 1779-1783. London: British History Online. 1767–1830. pp. 296–309. Retrieved 5 January 2020.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Office Of Lord Great Chamberlain". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. May 6, 1902.

- Thomas Mortimer (ed.). The British Plutarch. p. 115.

- Loades, D. (2004) Intrigue and Treason: the Tudor Court, 1547–1558 Harlow: Pearson, p.309

- "Office Of Lord Great Chamberlain". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. May 6, 1902.

- Great Officers of State: The Lord Great Chamberlain and The Earl Marshal Archived 6 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. The Royal Family. debretts.com. Debrett's Limited. Accessed 17 September 2013.

- "Position of the Lord Great Chamberlain following the demise of the monarch" (PDF).

- HL Deb, 15 March 2019 vol 796 c1213

External links

- www.debretts.com

- 1965 decisions regarding the Lord Great Chamberlain's responsibilities in the Palace of Westminster

- Planning Act 2008, s. 227(5)(h,i)

- Principal Office Holders in the House of Lords. House of Lords Library Note (LLN 2015/007), includes a very brief overview of the Lord Great Chamberlain

- www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

01.jpg)

.jpg)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.jpg)